self-publishing

I’m reading instead.

I’ll take your questions now. (Joke.)

Actually, that opening answer is very much true, for reasons I’ll discuss below, but it’s not the whole picture.

It’s also not the case that I’ve stopped writing entirely. I just turned in a story I was asked to provide for an anthology benefitting Democracy Docket, the organization run by Marc Elias fighting against the multiple voter restriction and suppression laws springing up all over the country. The anthology is the third in a series, Low Down Dirty Vote Vol. III, and my story is titled “An Incident at the Cultural Frontier,” based on my own experiences and concerns serving as a poll worker in my hometown, a liberal mixed-ethnic enclave in an otherwise overwhelmingly monocultural conservative county. Given the editor’s response to my submission—“You wrote the HELL out of that story”—I don’t believe my writing skills have atrophied in any significant way.

But I had hit a wall in the novel I’m working on. I’d managed approximately 150 pages and just felt adrift, not solely because of the work itse

The novel is the second in a series, and my attempts to find an agent for the first book have so far been unsuccessful. My editor, Zoe Quinton, is taking but another look at the manuscript to see if anything jumps out at her as being a red flag, but I’m increasingly inclined to believe it’s not the book that’s the problem. It’s me.

At a recent Craftfest luncheon (Craftfest is the teaching adjunct to Thrillerfest), an editor for a major publishing house remarked, “We don’t invest in books. We invest in writers.” He meant that publishers typically do not consider a book as a one-shot deal, but expect its author to deliver at least five books with increasing sales numbers book to book. If sales don’t rise, the writer is let go, and the process repeats with another pigeon—ahem, writer—for there is never a dearth of aspiring authors desperate to be published.

At the beginning of my career, I was one such writer. I had some notable success early and was even considered a rising star by my publisher, with the caveat, “David’s not for everyone.” (If they’d slathered that across the cover of my books, they would have sold better. But I digress.)

Be that as it may, after my sales failed to increase through the fourth book, I was let go. I’ve been wandering the publishing wilderness ever since, and the poor showing of my last novel, despite a prize nomination, most likely nailed the proverbial coffin shut.

I felt bad about this for some time but have finally come around to regard it instead as liberating. I continue to write if only to ensure that, as a teacher, I do not lose touch with the process, because I believe I owe that to my students. I need to be able to identify with their struggles and the best way to do that is to share them.

But it may be that I am one of those “pre-published” authors who goes the route of self-publishing, not to become rich or famous but to provide readers who have enjoyed my work a chance to read more of it. The numbers may not be impressive to a publishing house, […]

Read More

The forthcoming launch of any book is a heavy lift, rife with news to announce, people to call, and updates to publicize.

But if you’re launching a debut? It’s an especially daunting endeavor because, well, you’ve never done this before! And the pressure is high: a splashy, big hit debut can make an author’s career. But conversely, a debut launch that doesn’t meet author or publisher expectations can be difficult to stomach, and this puts additional weight on second or third titles.

How is a debut author to know what, exactly, should be on his or her “task list” in the months approaching their big book launch? No doubt, authors publishing via the indie route will have more on their plate, but even traditionally-published authors are expected to take on much of the heavy lifting these days.

Below, I’ve pulled together a “playbook” for debut authors. Consider it a list of ideas for debut authors in the year leading up to their launch.

By all means, take this list with a grain of salt: there may be items on here that don’t apply to your specific circumstances or a suggested timeframe that needs to be reworked.

9-12 months until launch

6-9 months until launch

Read More

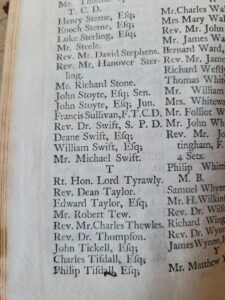

One of my favorite vintage bookstore finds is two volumes (out of three) of a 1742 translation by Rev. Philip Francis of the complete works of Horace. It’s interesting not so much for the translations (Francis turns Horace’s simplicity into contrived eighteenth-century rhyming heroic couplets) but for the technique Francis used to get it published. At the beginning is a list of subscribers – famous and/or rich people who paid a fee to be publicly seen as supporting the author. Among the viscounts and bishops is one “Deane Swift, Esq.” That would be Jonathan Swift, of Gulliver’s Travels.

Of course, writers today don’t have to persuade subscribers to pay for publication, selling their work on the same model that PBS uses to fund Masterpiece Theater. But from what I’ve seen of my clients’ experiences, being a successful writer nowadays involves a lot of skills that have nothing to do with actual writing.

Editing, for instance. This comes in roughly two different flavors – conceptual editing, which critiques how well your plot and characters work, and copy editing, which deals more with correct spelling and usage. (Full disclosure, conceptual editing is what I do for a living.) A lot of writers hire this out, especially the conceptual part, since it’s all but impossible to fairly critique your own work.

But good editing can be pricy, and many beginning writers on limited budgets have to learn to do it for themselves. There are <ahem> a lot of good books on what to watch for as you rewrite. Critique groups, where writers trade critiques on one another’s manuscripts, can be a help. But editing, especially copy editing, is a very different skill from writing, and it’s one you may have to teach yourself.

Read MoreThe artist’s tools: From Deb Lacativa’s studio, where all the magic happens.

My first Author Up Close post for 2021 features someone many of you might already be familiar with. Deb Lacativa is not only an active member of the Writer Unboxed community, she was also the 2016 WU Conference Scholarship recipient and returned to deliver the 2018 keynote speech. Deb also reminded me that she was, in her own words, “the first sacrificial lamb to the ‘All the King’s Slaughter … I mean, All the King’s Editors’ feature on Writer Unboxed.” The story Deb submitted for that series is now complete and will be published in a few weeks.

I not only wanted to interview Deb because she’s a gifted storyteller and creator (and friend), but because from the start, Deb defined success on her own terms. When she realized her genre-bending, 800-page debut novel would likely never get buy-in from a traditional publisher, she decided to take a different route to publication. In this Q&A we learn more about the novel and the choices that led Deb on that journey. Of course, if you know Deb at all, you know her answers are filled with the same mix of magic and mayhem her stories are. And, as an added bonus, at the end of this post, there’s a special treat.

GW: Tell us a little about how your writing journey started and when you went from dreaming about becoming an author to taking actionable steps to becoming one?

DL: I’ve been writing since I figured out that crayons didn’t taste good and had a better purpose. I was surrounded by adults who frequently had their noses buried in newspapers. The headlines seemed designed for a toddler to puzzle out, so I pestered for answers because I wanted in on this grownup magic. “MOBSTER SLAIN” above a lurid black-and-white photo on the front page of the NY POST was the first sentence I ever copied. But, beyond bs-ing all my teachers with style over substance at every opportunity, it wasn’t until 2005 that I started writing for an audience on my blog: The misadventures of a textile artist. I used it to be engaging. Sometimes, downright hilarious.

Then, over the course of sixteen months starting in the summer of 2012, both my parents and my husband, Jim, passed away. By January 2014, I needed to get out of the house and be with people who did not know me. It could have been throwing pots or axes, it didn’t matter just as long as there were no condolences. Meetup offered a writer’s group not far away. “Bring a sample of your writing.” I took my turn and was immediately hooked on getting feedback, good or bad. I’d found my heart and purpose for writing. I never dreamed of becoming a published author. It became an objective. Like learning to read and write, it was a skill set that I wanted to learn.

Read MoreAt the beginning of 2020 (which must be about 40 or 50 months ago, right?), I stumbled onto a book that literally changed how I think about writing. During an email exchange with my dear friend and fellow writer Jocosa Wade, she recommended an early novel by Chuck Palahniuk, whom I only knew as the guy who had written Fight Club.

I loved the movie by the same name, but had never read any of his novels. To be honest, I’d always been a little afraid to read him, figuring he would be way too hip, dark and cynical for me. But Jocosa convinced me it was time to take the Palahniuk plunge.

Being a perennially cheap bastard, I hit the public library. Yes, this was back in that gilded age when I would still do things like a) leave the house, b) go to a public library – or any other public place, and c) actually touch books – or anything else that other people had likely touched. Ah, such sweet pre-Covid memories!

In searching the library’s catalog, I noticed Palahniuk had just released a new nonfiction book: a writing how-to called Consider This. The book had just come out that month, but to my amazement my local library system already had a few copies, so I nabbed one. My three-word review is below:

DAMN, it’s good.

Seriously, after just the first two chapters, I put the book down and got on the computer to order my own copy for my Kindle, so I could begin taking notes in it. Yeah, it’s that good. The thoughts and ideas Palahniuk shares are clearly stated and directly actionable, not pie-in-the-sky theoretical stuff. And he has such a unique way of looking at some of the most basic components and mechanics of storytelling, which he explains in ways that immediately make sense.

I’ve read a TON of writing how-to’s (it literally is my idea of a good time on a wild Friday night), and it’s been impossible not to notice that many of them are expressing VERY similar ideas. Not Chuck. He looks at writing in some ways that are completely new to me. And he’s a marvelous teacher.

For example, Chuck suggests that we incorporate these three elements in our storytelling: description, instruction, and either exclamation or onomatopoeia.

Instruction? Onomatopoeia? Wait, what? Here’s how Palahniuk clarifies this directive:

Most fiction consists of only description, but good storytelling can mix all three forms. For instance, “A man walks into a bar and orders a margarita. Simple enough. Mix three parts tequila and two parts triple sec with one part lime juice, pour it over ice, and—voilà—that’s a margarita.”

Using all three forms of communication creates a natural, conversational style. Description combined with occasional instruction and punctuated with sound effects or exclamations: It’s how people talk.

Throughout the book, Palahniuk repeatedly touches on tangible, nuts-and-bolts aspects of writing in ways I have never before seen discussed.

Read MoreNearly every professional writer I know has dire things to say about sophomore novels, and for good reason. You don’t have to look very far at both trade and informal reviews to find scathing assessments of this or that writer’s “lackluster sophomore effort” or “disappointing follow up” to their popular debut novel. The second novel can feel doomed before you even write it.

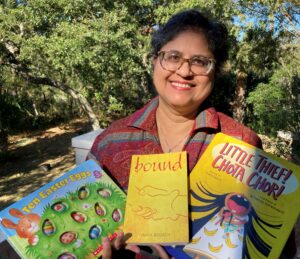

2019 was a special year for me, because it marked the publication of my sophomore novel. More accurately, one of my sophomore novels, because courtesy of the myriad and complicated layers of publishing, I am in the unusual and somewhat unenviable position of having published three debut novels, and three sophomore novels.

My first two novels were self-published under a pen name and, while the first one wasn’t a runaway success, it found its rather obscure niche. Year after year, it continues to sell in modest but reliable numbers. The second one, despite fitting squarely in that obscure niche, doesn’t sell at all and never has.

My next two novels were published by an independent press. The first one did well for a debut novel by an unknown writer from a very small publisher. It got some nice reviews and sold fairly well, all things considered. My second small press book foundered out of the gate. Unread, unreviewed, and generally unloved by readers who liked the book that came before it.

Then in 2016, what was technically my fifth novel was published by a major New York publisher. Because my first two novels under my own name had been with a small press, that first Big 5 book was billed as my “debut” novel. I got a great deal of the attending publicity and hype that comes with a well-received debut. There were times when it felt like publishing had miraculously restored my virginity, or at least made one last valiant effort to present this middle-aged redneck debutante to literary high society.

That third debut succeeded beyond my wildest dreams, but shortly after it made the New York Times bestseller list, I had to get serious about writing my next book. Hopefully my final sophomore novel. It came out last year and has generally been received in true second novel fashion. If first books are like first children, who get elaborate christenings and meticulously curated baby books, then The Reckless Oath We Made is a second child, who got a hurried sprinkling and a My First Year that is full of blank pages and blurry photos. Ah, we wanted to get a picture of the baby’s first steps, but the phone was on the charger.

There’s a common perception that a successful debut will help sell a second novel, but I don’t know any writers who believe that or who have experienced that. Part of the problem is managing expectations, because not every reader is willing to follow a writer to the next thing. I get a surprising (to me) amount of mail asking when I’m going to publish a sequel to All the Ugly and Wonderful Things. The answer is never, but it’s been enlightening to see the degree to which some readers attach to a book and don’t […]

Read MoreThere are plenty of great things about writing and publishing novels. But today, I’m not here to discuss any of them.

No, today it’s time to talk about three of the necessary evils a novelist deals with along the way. While these aren’t the only three tough tasks we have to tackle, they’re the ones I’ve heard writers decry most often as they work on their journey toward publication.

You need to write a query letter (ugh). You need to write a synopsis (ouch). And you need to be able to sum up your entire novel in one simple sentence (how?!).

So since each of these is a necessary evil, I thought I’d address a) just how necessary and b) just how evil each one is for the average writer. Let’s begin!

The Query Letter. How necessary? 9 out of 10 if you’re seeking traditional publishing; if you’re going the indie route, make that a 0 of 10. How evil? Mmm, let’s say 7 or 8 out of 10 for most of us.

Look, query letters are tough. But the job of the query letter isn’t to describe your entire novel. It’s just to whet the appetite of the agent to ask for more. If you can frame out what makes your novel especially intriguing, include any special credentials that show why you’re the right person to write it, and leave the agent wanting more, you’ve pretty much got it covered. Easier said than done? Absolutely. A necessary part of the process for hooking an agent? Pretty much totally, unless you happen to hook someone in a pitch session at a conference, and even then, you’ll probably want some kind of query/cover letter to re-introduce yourself when you send your materials along.

The Synopsis. How necessary? Maybe 7 out of 10. How evil? Yeah, that’s a 10. It’s the most.

Read MoreElizabeth’s marketing at work.

For my final installment of my Author Up Close series in 2019, I’m sharing a Q&A with Elizabeth Bell. Elizabeth and I e-met after both finaling in a writing award competition. Elizabeth is a craft genius—no surprise there; she has an MFA from George Mason University and works in the school’s library. When I caught up with her she was launching her novel, Necessary Sins, a James Jones First Novel Fellowship finalist. Her 26-year journey to publishing is fascinating, and our Q&A provides an honest look at the sometimes tumultuous road to publishing and how that road makes it even more important to define success on your own terms.

GW: You’ve got an interesting backstory when it comes to writing Necessary Sins, including how long you spent working on it. Will you share what inspired you to write about this particular subject?

DB: When I was eight years old, I visited Charleston, South Carolina. I fell in love with its gardens and architecture and wanted to set a story there. As an adolescent, I devoured Colleen McCullough’s The Thorn Birds, John Jakes’s North and South, and Alex Haley’s Roots. I wanted to write a saga on that scale, something with multiple settings that would follow characters across decades. Those stories are great escapism and drama, but they also taught me about history and place.

The central family in my saga, the Lazares, is multiracial and “passing.” This was partially about secrets—family sagas always revolve around those—and partially about history, getting at the heart of the contradictions that are the American Dream. But the very first seed of the Lazares’ racial makeup came from my mother. She read an early draft and told me Caucasian people don’t have black hair; it would have to be dark brown. But my Lazares had black hair; I just knew it! Caucasian people do have black hair—the Welsh, for instance—but somehow the “problem” of black hair simmered in the back of my mind. I was puzzling out David’s (one of the main characters) personality, what made him reluctant to trust and reveal his true self, as well as why his uncle Joseph might choose to become a celibate priest. Joseph is very pious, but as a priest, he’s also hiding in plain sight. My characters are products of their time, but I wanted them to resist racism. What might make them view the world differently than the slaveholders around them and work for justice? My answers to these questions coalesced into the Lazare family having African ancestry.

It’s taken me a quarter-century of research and revision to become a wise enough person and good enough writer to tell this story.

GW: You went to great lengths to authentically portray characters with African ancestry. Will you share some of the things you did to help with that?

Read MoreUnder the pen name Anna Schmidt, Jo Schmidt has written over thirty novels that have collectively sold over half a million copies. She is also the author of Parkinson’s Disease for Dummies and several books on eldercare published by AARP. Her latest novel, The Winterkeeper (March 2019) is her first literary fiction release. A former marketing and communications professional for two international corporations who has also taught at the college level and run a Mom-and-Pop adult daycare business with her husband, Jo is now retired and focused only on writing. She splits her time between Wisconsin and Florida.

—

Breaking out of the Genre Pigeonhole: Tips From a Romance-Turned-Mainstream Novelist

When the love of my life died seven years ago, it was like losing half of myself. Aside from the deep emotional toll grief takes, it brought professional challenges. As a career romance author, writing love stories suddenly became downright painful.

For years I had been contemplating breaking away from the genre fiction mold I’d been embedded in for decades, but now, moving away from romance fiction felt vital. I no longer wanted to write ‘happily-ever-after’ stories. I wanted to write ‘what-happens-next’ stories. I was fascinated with telling the story of a marriage after the honeymoon—years, even decades after. I now knew that story—the laughter and the tears of that story.

Many writers, myself included, start their careers with a singular quest: to get published. It follows the outline of the “if a tree falls in the woods” adage: You can work day and night on a manuscript, but if it never reaches readers, did it ever really get written?

If you’re lucky, you might get published. You may even have a bit of success, as I did. And I learned an important lesson: With success comes restrictions. I had sold over 500,000 copies of my romance works. How hard could it be to pivot away from romance, to be able to tell the more complex stories I wanted to tell?

The answer: Hard. Very, very hard. In the end, publishing is a business. Turning out romance novels for the legion of readers is big business. Having worked in the corporate world for two international companies, I understand that bottom-line philosophy. I don’t have to like it; I just understand it. And the bottom line was that these publishers needed me to keep writing the stories that would feed the appetite of genre readers and drive consistent, predictable sales.

So when it was time for a change—or at least a shift—my agent pitched my new novel concept to a number of publishers…and I got some of the nicest rejection letters I’ve ever received in all my years doing this writing thing. They liked the story, the writing, the characters. But they couldn’t see a viable route to cash in.

Luckily, my skin was thick, and I learned a lot. If you find yourself in a similar position, hoping to reinvent yourself as a writer and storyteller, here’s what you can do:

Read More