Process

I know this is a dated reference, but there’s a scene in Transformers: Revenge of the Fallen (the 2nd movie) where Sam Witwicky and his companions enter the Udvar-Hazy Air and Space Museum in Dulles, Virginia to find the ancient decepticon, Jetfire (the SR-71). After locating him, they all run through the hangar doors into the parking lot airplane boneyard in Tucson, Arizona.

With no explanation.

If we’d been told there was a portal of some kind, or Jetfire teleported them there, I’d have been fine with it. Or if this had been some generic museum in a generic, unnamed place. But it wasn’t.

Maybe the explanation was left on the cutting room floor. 🤷🏼♀️ Or, it’s just entertainment and I shouldn’t care. But I happen to be the perfect storm of movie viewer who’s lived near both places, and because I’m a dork, the disconnect bothered me. Please tell me I’m not the only one who gets pulled out of a story by inconsistencies and mistakes.

Like the author who wrote about Prattville, Alabama as if it were in the middle of nowhere, far from civilization. (It’s a suburb of Montgomery.)

Or the book where the main character lives in a bungalow in Pismo Beach, California that’s on an isolated hill overlooking the ocean. (Um, all the private ocean-view land there has houses packed close together, even the big ones on the hill.)

Or TV shows like NCIS where they mispronounce Lompoc, Calfornia (it’s poke, not pock) and Ramstein (the “ei” is eye, not ee) Air Force Base.

Unfortunately, I could go on because I tend to fixate, but you get it. It’s the tiniest of errors made by people writing about places and things they’re unfamiliar with that can pull you out of the story and make you question everything else’s validity.

Or, is that just me?

In the early days of my writing, I got rightfully called out by a contest judge for calling a dock a pier. Now that I live near both, I cringe.

You can’t know what you don’t know, so that definitely won’t be my last error, but making this kind of mistake is one of my biggest fears because of readers like me. (Also, I really dislike looking stupid. Enneagram 5, if you’re into that.) It’s the reason I mostly write about places I’ve visited or lived, or completely make up a location (usually based on somewhere else, though, the way Sue Grafton based Santa Theresa on Santa Barbara), and still do extensive research.

(Sidebar: This is a whole topic on its own, but not knowing what you don’t know is also why paid sensitivity readers are important, especially if you’re writing about someone who’s part of a marginalized community.)

Even if you’re writing fantasy or sci-fi, you should probably know what’s come before you in the genre, and ensure the world you build makes sense. Made-up worlds can benefit from roots in real history and settings, and universal experiences, to ground the reader in an unfamiliar domain.

I know not everyone likes research, but for me the joys include:

Read More

Please welcome WU’s newest contributor–creative force and debut author, Jillian Forsberg!

Jillian holds a master’s degree in public history from Wichita State University and a bachelor’s degree in communication and history from McPherson College. Her historical research has been published in academic journals and she was the editor for Wichita State’s The Fairmount Folio.

Jillian’s research into little-known historical events led her to discover the story of Clara the Indian rhino, who dazzled Europe in the 18th century. Clara’s true story formed the basis for Jillian’s debut novel, The Rhino Keeper, which releases on October 22nd from History Through Fiction. And–fun fact–because The Rhino Keeper set pre-order records for her publisher, Jillian got to spend some quality time recently feeding rhinos!

“They must have been bonded. And so begins the harrowing, heart-wrenching tale of a man and his beloved rhinoceros, Clara. Inspired by real-life events, The Rhino Keeper by debut novelist Jillian Forsberg illuminates the extraordinary connection between humans and animals. Spanning two centuries, The Rhino Keeper is both a historical mystery and a tale of old-world adventure, reminding us that even the wishes we take to our grave may someday come true after all.” – Sarah Penner, NYT Bestselling Author of The Lost Apothecary and The London Séance Society

“Rich with adventure, historical detail, and love of all kinds, THE RHINO KEEPER is an enchanting true story. Jillian Forsberg brings Clara the rhinoceros and the humans who cared for her to vivid life, deftly interlacing the dual timelines to create a poignant tale that spans both continents and centuries. Just as the 18th century Europeans who flocked to meet Clara could not help but be changed by knowing her, readers of Forsberg’s accomplished debut will find their hearts expanded with each page they turn.” – Molly Greeley, author of MARVELOUS

Jillian’s passions lie firmly in the 18th century. When she isn’t tending to her bridal store, you will likely find her browsing the closest antique mall or reading every label at a museum. She’ll most likely be wearing vintage dresses–except when she’s feeding rhinos.

Learn more about Jillian and The Rhino Keeper on her website, and follow her on Instagram and X.

“Your antagonists are mustache-twirling Muppet-like characters,” said my editor. “We have to make them real people.”

Mustache-twirling? Muppet-like!? Good lord. Had I lost touch with writing bad guys?

“How do I do that?” I asked, my heart in my throat. I was prepared for the worst. Huge rewrite? Scrap everything!? Instead, I was assigned some surprises.

Relatable antagonists are some of the most difficult to write in fiction, particularly historical fiction, where in our mind’s eye, we see cloak-draped villains as an easy out. But my editor was right – as editors usually are – and my antagonists needed depth, substance, and work.

My assignment was to study well-done villains in movies and reflect upon myself. Myself? Luckily, movies came first.

The two movies on the docket: Gangs of New York and Footloose. I laughed at the suggestion. How could two very different movies, neither set in the right time period or place, help my book, set in […]

Read MoreMaybe, just maybe, the inspirations for my WU posts are at times a little too on the nose. I mean, who would have thought that four years after a global pandemic, three years after an assault on the US Capitol, and mere weeks following the felony conviction of a former President, a subsequent assassination attempt on his life and the unprecedented departure of the sitting President from his reelection bid would prompt me to consider the unraveling of social order and how it is depicted in fiction? Really, what are the chances? Yet here I am contemplating all of that, synthesizing it in my writerly brain, and offering it up for consideration by the WU community. As obvious as the topic may be, I chose to stick with it for one simple reason. I can’t imagine a better time, given that understanding human nature and its tribal rhythms is such a driving force behind fiction, to explore how best to convey the collapse of a story world, be it on a global or an intimate scale. So, let’s dive in, shall we?

My first thought on the topic is merely an observation – Make note of how you feel about recent events. As writers, we possess an innate ability to draw upon personal experience to breathe life into our tales. Emotions from real experiences inform fictional scenes all the time. This bewildering moment in time is no exception. Whatever you may be feeling – rage, frustration, melancholy, paralysis – are precisely the emotions with which your characters will grapple while navigating the rapid demise of their world. Own it, absorb it, and remember it – the feelings will be useful someday on a future project, if not your current work in progress.

Beyond that, I offer the following ideas on capturing the disintegration of social order in fiction:

Stand the Dominoes Carefully

If you’ve set out to craft an apocalyptic tale, this may seem obvious. But it’s worth noting for stories operating on a smaller scale as well. A reader needs touchstones in your story world to which they can relate – authorities, cultural entities, buildings, symbols. As your story opens, introduce them and underscore, subtly, their importance to the normal order. Perhaps a young protagonist is preparing for a coming-of-age ritual, religious or social. Perhaps a secondary character works for the government, holds financial power, or maintains civic infrastructure. A church, courthouse or town square may occupy a prominent place in the community. Introduce these elements early and weave them into your opening act, laying the foundation of what normality looks like for your cast of characters.

In the novel All the Light We Cannot See, Anthony Doerr introduces the reader to the Muséum national d’Historie naturelle in Paris in the opening pages. The father of the young blind protagonist, Marie, is a locksmith employed at the institution, which houses a rare gem that plays an essential role throughout the tale. The grandeur of the museum is evident in her reverent descriptions. Later, as German forces approach the city, Marie senses but fails to appreciate furtive preparations underway to remove and conceal its priceless natural objects. When the city is eventually overrun, she sits alone inside the locksmith office, awaiting her father. She feels […]

Read Morephoto adapted / Horia Varlan

Sometimes, your protagonist just won’t cough up her secrets. Not even to you, her creator. How rude!

As a writing instructor, I must come up with examples of various techniques all the time. Not novel-length examples, of course—I use published works for that—but more like microfiction, whose entire arc can be taken in quickly. After all, a story is a story, and should engage the reader whether its form is short or long—and for that, one needs the protagonist to reveal her depths.

That doesn’t mean they’ll become an open book—that’s not in keeping with someone who has good reason to be reticent. In real life, I know plenty of people who will not reveal their hearts. It’s as if doing so would hurt as much as cracking open their own ribcage. Maybe they’ve been taught that showing emotion is a weakness; or maybe, if they let one emotion escape, they fear that the rest will rush out and drown them in an unstoppable tsunami. Vulnerability may feel dangerous due to previous trauma from which the character has never recovered. Or maybe shame has clamped down those emotions, creating a pressure cooker that will one day blow. All of this could be great for story—if only your protagonist would tell you what’s up. But due to their very nature, they aren’t likely to trust anyone—even you.

Here are the challenge questions I posed to the tormented protagonist I hoped to feature in a recent short example. I took down her answers longhand, as the flow of ink from mind to hand seems to connect us. I write my question in a journal, then write the protagonist’s answers in the voice of the character.

Q: What is your name?

Nada.

We were off to a slow start. But I sensed she wouldn’t talk to me at all until I named her. I called her Patricia Jeffers and moved on to the next question—at which time she butted in to say, “It’s Hannah. Hannah Jeffries.”

Okey doke then.

This isn’t the first time this happened to me. When writing my last manuscript, a featured secondary character I’d named Kristof butted into my writing time one day to say, “Stop calling me that. I’m André.” While explaining the oddities of the subconscious mind is beyond the scope of this post, it makes sense for a character to stand up for themselves. They may not want to vomit up their dark secrets, but their identity is important to them; they don’t want to be manipulated into a role they aren’t suited for any more than you do.

Q: May I feature you in a very short story about a woman who is angry that her childhood climbing tree was cut down?

A one-shoulder shrug. She’s going to be a tough cookie.

As a teaching tool, my goal had been to show how, in a first draft, it can be helpful to overwrite the protagonist’s feelings until you hit emotional bedrock (note the named emotions underlined in the next paragraph). So far, I’d written:

After coming home for summer break […]

Read More“Do anything rather than marry without affection.”

(All quotes from Pride and Prejudice, by Jane Austen.)

Memorable stories often revolve around one big idea, commonly known as the theme. Theme has been defined a thousand ways. I envision it as the broth in which the story stews, the skeleton on which the story hangs, the night skies in which the constellations shine.

The theme imparts a general truth cloaked within the particulars of the story. It gives coherence to the plot and a direction of growth for the characters. “What constitutes a lasting friendship?” is a theme of Tomorrow and Tomorrow and Tomorrow, by Gabrielle Zevin. “What is the price and reward of sisterhood?” is a theme in The Once and Future Witches, by Alix Harrow. “How is truth warped by the goals of the narrator?” might be a theme of Trust, by Hernan Diaz.

“There is, I believe, in every disposition a tendency to some particular evil–a natural defect, which not even the best education can overcome.”

The overarching theme of all of Jane Austen’s books is “how do human weaknesses stand in the way of love?” She gives us pretty unsubtle hints. The vices that name her books — pride, prejudice, over-reliance on sense, excessive emotional sensibility, and succumbing to persuasion — all thwart the relationships we know were meant to be.

The thematic truth of Pride and Prejudice, for instance, is that humility (the opposite of pride) and accurate judgment (the opposite of prejudice) are necessary for love to prosper. Pride overvalues oneself, while prejudice undervalues others. Both are erroneous ways of thinking that undercut meaningful relationships.

These ideas may be true, but simple statements of this sort fail to engage a reader. So how does a successful writer expose thematic truths without resorting to bald, uninteresting claims? The answer, as so often, is show, don’t tell, and Robert McKee’s Story presents one way to do it.

McKee’s “thematic square” is a rubric for expanding the impact of a story’s theme. Desmond Hall explained it in more detail last year. Essentially, start with a big concept-the thematic truth–then view it from several incomplete or conflicting angles. McKee organizes these angles through four complementary lenses:

Although written nearly 200 years before the publication of McKee’s handbook, Pride and Prejudice is a masterclass in how to apply his thematic square. Its storylines include a myriad of characters whose personal lives are a mess. Together they illustrate how subpar relationships result from a lack of one or both of the thematic virtues of humility and accurate judgment.

1. Thematic truth: Pride and prejudice get in the way of true love.

“He was the proudest, most disagreeable man in the world, and everybody hoped that he would never come there again.”

Both Elizabeth and Darcy are consumed by these faults as the story begins. Their arcs of change require seeing the error of their ways.

(Yes. This is all terribly simplified and incomplete and I apologize to the true fans out there. Leave your additions and corrections in the comments!)

2. Truth contradictory: Excessive humility

“He may live in my memory as the […]

Read More

The protagonist in my second novel is a sixteen-year-old boy. Since the book was published in March 2023, the question I’ve been asked most frequently by readers and reviewers, especially men, is how I was able to write a character so drastically different from myself who seems like he could be a real person.

When I was first asked this question, I didn’t have a good answer. I just created a character that felt real to me, I’d say. But after being asked multiple times, I decided to put some thought into it. The tips below are things I regularly do that have helped me make my fictional characters feel like people you might actually meet.

I observe people carefully.

Because I’m an introvert, I’ve always spent a lot of time watching other people, both friends and strangers, often without realizing it. Doing this has allowed me to pick up on subtle traits and habits individual people have, such as the way someone ties their shoes (lefties tend to use the “rabbit ear” method), or the things some people do when they feel stressed or nervous, like repeatedly adjusting their eyeglasses.

Sometimes these traits can be age-specific or more commonly seen in people of a certain gender, culture, or ethnicity. After a lifetime of observing people in my own family, I’ve come to believe that many of these behaviors are inherited or at least “contagious.”

Also important is noticing the way people are dressed. A habitual runner might still have his sweatsuit and sneakers on when he goes grocery shopping. A trial lawyer might always be wearing a tailored suit when she picks her kids up at school. Someone who’s wealthy, or trying to appear so, might carry an expensive handbag when wearing an otherwise unremarkable outfit.

When I sit down with my laptop to work on a novel or story, I think about the characters and what similarities they might have to actual people I know or have seen, and I try to incorporate some of their traits into my characters’ personalities.

I listen to the way people talk.

Because dialogue, both spoken and internal, is an essential part of any fictional story, paying attention to the way actual people talk is important. Someone’s accent, even a complete stranger’s, can often tell you volumes about that person whether you speak to them or not.

Because I have lived in a city that has a large population of immigrants from around the world for the last twenty-plus years, I’ve gotten good at discerning accents. I can tell the difference between a native Spanish speaker from Puerto Rico and one from the Dominican Republic, for example, by their accents when they’re speaking English.

One of the most interesting things about paying close attention to the way people speak is when I hear someone who is trying to hide their accent. I first picked up on this after meeting the wife of a colleague of my husband’s who was from Alabama. To a casual listener, she might not have seemed to have had any accent at all, but there were subtle markers in the way she pronounced certain […]

Read Morephoto adapted / Horia Varlan

Early reading influences can have a powerful effect on a future writer. In her May post, In Praise of Passionate Persistence, WU contributor Kristin Hacken South shared an early influence of hers, The Phantom Tollbooth. Her post inspired such nostalgia in me that I wanted to play, too.

When I thought it through, though, the story that offered up the most useful and practical lessons wasn’t one of my favorites. Yet its impact was memorable, and only in retrospect have I appreciated its lessons about story and the writing life.

It began:

In the old days, no one but a king could have a dog for a pet.

Published in 1958, written by Benjamin Elkin, and illustrated by Katherine Evans, it was called The Big Jump. If you’re interested, Grandpa Brian will flip the pages and read it aloud to you at this link. The following plot summary contains spoilers.

When the king walked his dogs, all the boys and girls came out to watch. One day a pup ran away from the king and straight toward a boy named Ben. He told it to go back—he didn’t want to get in trouble—but the pup licked his hand. The king took note.

Ben wanted the dog badly, but alas, he was not a king. Until the king told him, he didn’t even know that to be a king, one had to be able to do The Big Jump. Ben asked what The Big Jump was but the King was gone—and reappeared on top of his palace. If Ben could jump that high he couldn’t be a king, but he could have the dog. For now, he could keep the pup for one day.

At home, Ben stacked wooden crates and practiced jumping. They were nowhere near as high as the palace, and yet he failed, over and over. Then he had the idea to vault with a stick, and was able to jump to the top of four boxes—but no more.

The pup jumped onto the first box, then the second, then the third, and then sat on top of the stack. Ben knew how to jump to the top of the palace. After he demonstrated for the King, the other children mocked him, saying that they could all do it that way. But the King pointed out that they could only do it now because Ben had showed them how. He won the pup.

Here are 8 of this story’s metaphorical lessons for writers.

Read More

One of the kindest reviews I ever received on my writing was from a reader who said I had the gift of crafting stories within stories. The compliment gave me goosebumps, for it acknowledged a skill I hadn’t set out to master. Later, when an opportunity arose for me to ask what prompted the observation, the reviewer highlighted two examples. Both centered around a main character revealing an aspect of their lives to another character – the first sharing a family history, and the second opening up about a painful emotional wound.

At the time I pondered why those moments, introduced in dialogue, had left an impression. Both scenes had come naturally; the kind you picture clearly and transcribe to the page with minimal angst or later revision. And ever since, I have a heightened awareness when during written works or visual performances a character comes to the fore to share their own story. These are not soliloquies, which fell out of favor long ago, even on stage. But perhaps they serve a similar purpose, an opportunity to shine a light upon a single character as they speak their truth or define themselves in their own words, outside the established structure and rhythms of the narrative. Spoken aloud, in the character’s own voice, these stories within stories can create ripples in the primary storyline.

Clearly the idea captivates me, but it seems rarely studied as a technique like other aspects of writing craft. For that reason, I thought it might be a worthy exploration with my writing family, all of you at WU. To kick things off, here are a few of my thoughts on the power that can come from moments when you allow a character to steal the microphone for a few pages.

A Compelling Approach to Backstory

We have all seen the movie or read the tale – there are so many from which to choose – set in a dystopian future or a dilapidated boom town. Invariably, at some point the explanation comes, the why behind the collapse of what had once held such majesty. It’s the backstory dilemma writers strive to handle well, how to inform without dragging down the present action. Movies may get away with an introductory narration, a literal data dump of how to receive page one – “long ago, in a galaxy far, far away ….” You get the picture.

But contemporary novels are trickier. Some writers are skilled at employing internal monologues. I have used them myself, and sometimes they manage to escape the dreaded “gazing into the mirror” phenomenon. But even when handled with aplomb, they can become repetitive. If every new character spends a few minutes musing about their current predicament, or their past, tales will all too often land in a reader’s “maybe later” pile, if they get published at all.

That dynamic can change if, when the proper time arrives, the past comes alive through the eyes of a character. An elderly woman eking out an existence on a failing farm telling a beloved granddaughter about her own nuptials decades earlier, a longing evident in her voice, can provide a window to the past. The details she shares of that special day – the wine, the music, her mother’s blessing – all […]

Read More

“What do we say about coincidences? The universe is rarely so lazy.” –

Sherlock, S3 Episode 2

Writing is a leap of faith, a nail-bitingly risky foray into the unknown. We’re adventurers following strange paths, never certain whether we’ll find our way or what type of reception we can expect if we finally arrive. Is it any wonder, then, that we look for encouragement along the journey?

Sometimes that means stumbling across it in unexpected places. When I was writing my last book, which features Peter Pan and talks about stars, I found both everywhere. Peter Pan figurines in odd little gift shops and tattoos of the boy who wouldn’t grow up inked on random passersby; stars scribbled on bathroom stall doors and folded out of origami paper. These signs showed up at odd times and hours, often when I was in despair about ever pulling the book together, and lifted my mood enough to carry on.

I’ve since started a new project, and to my delight the magic continues. I’ve found symbols that represent my new story by the side of the road when I’ve been out jogging, on record covers in second-hand stores, and once, most memorably, in a flower shop in Salem, Massachusetts (home of the WU Unconference).

These little signs never fail to surprise and enchant me. It’s as if the universe is whispering in my ear, telling me I’m on the right path, that home is just around the corner if I’m brave enough to persist.

I don’t really believe this, of course. Instead, I think these “signs’”are like the pink elephant theory—once you’re thinking about something, it’s almost impossible to stop. These physical displays are just my subconscious working overtime, struggling to find patterns and story threads wherever I look.

But still, they make me happy. And I try to turn them to my advantage by asking myself two questions when they appear:

The first is simply: How does this item relate to its setting and can the juxtaposition between the two help me think about my writing in a different way?

For example, during the writing process for my last book, I found a tiny golden star on a park bench. The juxtaposition between the star—shiny and bright—and the park bench—worn and dingy—had me considering what would happen if magic entered the real world from another place. Would the magic somehow be tarnished, or would it stay bright? These thoughts eventually helped me form the “rules for magic” in my story.

The second question I ask is: What does this mean? I’m not necessarily looking for a universal truth – although if I can suss one out, that’s a bonus. Instead, I’m thinking about what the item’s story is in relation to the person or event that placed it there.

The star mentioned above could be a trinket abandoned by a child (leading me to think about the fleetingness of childhood and the emotions that arise from that) or it could have been deliberately placed on the bench in memory of a person or relationship, or any number of other scenarios. What interests me most is whether any of these resonate with what I’m working on, […]

Read Morephoto adapted / Horia Varlan

Thanks to the 24/7 information kiosk that is the internet, anyone with a smart phone can now become a lay doctor. This can be handy if you wake up in the middle of the night with a stabbing pain and learn that the burst appendix you feared was probably just gas. But for a while now, I’ve been wondering if immediate access to all things medical is always good news for novelists.

Back before it only took a tap of the finger to paste a celebrity photo onto a Pinterest board or borrow a bio from a known sociopath, writers imagined their characters into existence. If that character’s specific story included a mental or physical health challenge, instead of cruising the ’net for a diagnosis, the writer might wonder, If something in a man’s brain made him go blind, how might that test his wife’s assertion that her plastic surgeries were meant to please him? In that story, the husband’s localized headaches and blurred vision might be convincing enough. Consider the law of diminishing returns: these days, a writer can spend hours if not days of their precious writing time googling whether shrapnel from the Vietnam War could migrate slowly through the brain to cause similar damage decades later. (If that sounds oddly specific, um, well, I have no idea why).

I’m not convinced we need to do that.

Prioritizing the protagonist’s character and her story before doing research is still a solid approach. In the May/June issue of Writer’s Digest magazine, author Alyssa Cole spoke about her process creating the lead character for her newest thriller, One of Us Knows, who is the host of a “system”—the group of personalities formed when an individual has dissociative identity disorder. Cole first came up with the basic story idea: “What happens when the main person who is causing trouble is also the one who has to get them out of trouble?” She says, “I didn’t want to read someone’s story and then be like, Oh, let me make a story based on this thing.” Only then did Cole check primary sources to ensure that she was “accurate within reason and respectful.”

Put story first

For my debut novel, I decided that a formal diagnosis for my protagonist would fail to communicate one of the most frustrating realities in treating mental illness: it’s the person who doesn’t think they have a problem that must seek the diagnosis. The words “body dysmorphia” also would have ripped the heart from my story. It was her disordered thinking about her body that kept her butting up against the unwanted consequences that pressured her to change. I chose differently for a major secondary character. Her known cystic fibrosis diagnosis averted any “medical mystery” that might upend focus on the story I wanted to tell, of how two woman of the same age—one with a strong body but a weak spirit, the other with a hearty spirit but a weak body—might influence each other.

Impaired characters who remain undiagnosed are common in literature. Since 1843, when Edgar Allan Poe’s The Tell-Tale Heart was published, it has been critics—not the text of the short story itself—that spoke of the […]

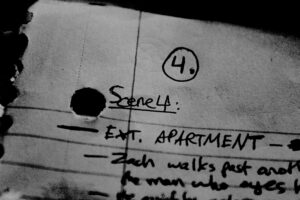

Read MoreThis year I decided to try my hand at screenwriting. I didn’t think it would be radically different, and in a way, I was right. Everything I’d learned about character and plotting gave me a leg up on initial creation.

But when it came to actually writing the story, in that format, the difference was mind-blowing.

Here are the biggest takeaways I’ve gleaned… so far, anyway. I sense there’s even more I’ve yet to learn.

IMPACT.

Imagine taking a 300-500 page novel, and then carving it down to 90-120 pages, without summarizing or losing depth.

Much like equipping a sailboat, every bit of usable “space” needs to serve a purpose – ideally more than one. There is no room for pure decoration. Every bit of action, setting, character, and dialogue needs to do several things at once, in an interconnected manner. It also must engage the audience, while moving the story forward.

(Note I didn’t include exposition. More on that in a sec.)

As Pascal once said, “I have made this longer than usual because I have not had time to make it shorter.” It’s often quoted in reference to the difficulty of writing short form fiction versus long. Screenwriting showcases this problem. It’s a puzzle, a fiction sudoku. The approach, however, can also apply to prose. The trick is to make sure you are applying it every time.

VISUAL.

Because film is a visual medium, there is an expected emphasis on both setting and action. “Show don’t tell” becomes less a guideline and more a mandate, especially since no exposition should be included. (You could include exposition in action blocks, but it’s frowned upon. If you can’t show it, the audience doesn’t know it, and there’s no point in including it. Also, you’re eating up precious page real estate.)

While writing isn’t visual, the concept still applies. You don’t need to abolish all exposition, and in my opinion, you shouldn’t. Still, talking heads in generic settings are static, both on screen and in prose.

The solution is ensuring that the environment your characters are in, and the action they’re taking in the scene, is not only more engaging, but provides context, emotion, foreshadowing, and most of all, conflict and tension (positive or negative.) Study what you’re trying to communicate, and see how you implement that visually. It’s about making sharper, smarter, and, per the last tip, more impactful choices.

SUBTEXT.

This is most often understood in terms of dialogue, which often takes up 40-60% of a screenplay.

You rarely want “on the nose” dialogue, baldly stating what a character is thinking, feeling, or planning. Subtext not only sounds more natural, it’s a multi-tasker. How something is said communicates character and environment. It injects emotion. It’s a good source of conflict. And of course, it provides information, but not in so glaring a way that the audience is yanked out of the immersive experience.

Subtext is a distillation of meaning, not just providing, but relying on situational context and characterization to reveal story. This ties into the previous point: with the right setting and action, and with a clear understanding of the character, your dialogue will be a lot easier to express in terms of subtext. All the moving pieces, interlocking like the gears in a Swiss watch.

TRUST.

Billy Wilder, one of the greats in […]

Read MorePlease welcome back multi-published author Henriette Lazaridis as our guest today! Henriette is the author of The Clover House (a Boston Globe bestseller), Terra Nova (which the New York Times called “ingenious”), and Last Days in Plaka, which was published just yesterday, on April 9th.

Last Days in Plaka is Henriette’s most personal novel to date. A first generation Greek American and only child of expat parents, Henriette grew up speaking Greek as her first language and listening to her father relay Homer’s Odyssey. It’s no wonder that she has set her latest novel in Greece or that the story centers on issues of identity and nostalgia.

It’s also told via an omniscient narrator “who knows when to invoke the reader and when to extend their reach beyond the scene at hand,” said early reader Jesse Hassinger of the Odyssey Bookshop in South Hadley, MA.

We’re going to dive a little more deeply than we generally do into the specifics of a book today, to better understand why Henriette chose to write this novel with a narrator’s voice. With that understood, a little more about the plot to orient you:

What do you do when you feel like your time is running out? Or when you’re uncertain that the time you’ve spent on earth so far is even meaningful? Searching for connection to her Greek heritage, Anna has left her parents behind in Astoria, New York to come to Athens, working at a gallery by day and making clandestine graffiti art by night. Irini is an elderly widow, once well-to-do but now dependent on the charity of others. When the local priest brings the two women together, it’s not long before they form a connection. Anna’s friends can’t understand why she spends so much time with the old lady, yet Anna becomes more and more rapt by Irini’s tales of a glamorous past, the mystery surrounding her estranged daughter, her lost wealth and the earthquake damage to her noble home. Together, they join the priest’s tiny congregation to study the Book of Revelations ahead of a pilgrimage to the religious site on the island of Patmos. Desperately seeking to find her purpose, Anna makes a reckless decision that endangers her life, exposes Irini’s web of lies, and forces herself to confront the limits of her ability to forgive.

How did Henriette land on an omniscient voice and why did she know it was right for her novel? Read on. You can also learn more about Henriette and her novels on her website.

When I began writing my third novel, Last Days in Plaka, the voice in which the story announced itself to me was omniscient. Someone–I had no idea who–was telling this story of two women in Athens in the summer of 2018. “This is not her story,” the book began in my head one August night. “She stole it from the young woman who did not know until the end that it was hers.” The novel came into existence right from the start as the tale told by someone who knew it all, who knew the end–and who knew even before I did that the character of the young woman would come […]

Read MoreWelcome to a new edition of Desmond’s Drops!

This month, enjoy three new drops focused on one topic: Blake Snyder’s genres from his classic book, Save the Cat!

Email subscribers, please click directly to staging-writerunboxed.kinsta.cloud to view, or visit all of Demond’s Drops on YouTube.

Look for more of Desmond’s Drops in May!

Have your own bit of wisdom to share? Drop it in comments.

Read Morephoto adapted / Horia Varlan

The email assault continues without rest, its dire warnings and in-your-face messaging delivered in yellow highlighter, handwritten red ink, and ALL CAPS WITH MULTIPLE EXCLAMATION POINTS!!! [Yawn—is it November yet?] I’ve never been more grateful for the phone setting that rejects calls from people who aren’t in my contacts.

But seriously—is a novelist’s life ever truly free of political content? Listen in on some memorable moments I’ve plucked from the last twenty years of my life.

Heard at a recent book club meeting:

When putting forth as our next book club pick Emily St. John Mandel’s Sea of Tranquility, I shared from the book description that one of the point-of-view characters lives on “the second moon colony.”

“No.”

I was surprised to be cut off so soon. Typically we are an open-minded group, willing to read books that fall outside our usual fare. Thinking this was simply a call for further convincing, I shared the accolades: over 26,000 reviews that averaged 4.3 stars, starred trade reviews, “Best Book of the Year” nods from sixteen reputable sources, President Obama’s reading list, plenty to chew on and discuss…

“That scares me too much,” my neighbor said. “I can’t think about that kind of future.”

Her admission sent a thrum through a room gone suddenly quiet.

Instead, my neighbor steered us toward the other novel I’d put forth, Z, A Novel of Zelda Fitzgerald, written by our WU friend Therese Anne Fowler. I suppose my neighbor’s thinking was that the conflict in a historical—which in this case included the financial and psychological struggles of a life in publishing, a woman’s fight to be heard among the men who marginalize her, and the deleterious effects of drinking to excess on health, relationships, and a career—might produce less anxiety, since it had already been resolved.

Hmm.

Heard at a party, the summer of 2016:

“I refuse to talk about anything political.”

That will be a trick, I thought. But I knew as well as the speaker did that her politics would not be particularly popular in our grouping, so I asked, “What would you like to talk about then?”

She said, “I don’t know, the arts.”

Oh boy did that poke a very political bruise for me, and anyone else present whose underpaid work to enhance and preserve our country’s culture—our very humanity—had depended on grants from the National Foundation on the Arts and Humanities. With everyone watching their steps, the topic quickly petered out.

“Okay then, pets!”

Talking about fur babies might sound like a subject insulated from political intrigue, but the one and only time I had to go to court to defend my rights was after a neighbor, ignoring leash laws, allowed her German shepherd to run into the street, pick up my cockapoo by the neck, and shake it until he tore his skin. My peace-loving Max could still walk, thank goodness, but he was so afraid to do so I had to carry him up and down hills for more than a half-mile to get home, even as my own arms were shaking. Then […]

Read More