Inspirations

My husband recently took a trip out of state. My kids went away with grandparents, and I was alone for three days.

“You should just relax,” my husband said before he disappeared into the airport.

Instead, I pretended I was on a writing retreat.

I wrote more and for longer hours than I have in a very long time. And even when I broke for dinner, I felt passion for my stories drawing me back. I had to talk myself out of continuing to write and instead spend an hour reading before bed.

Without any demands on time outside of my own needs (and yes, I forgot to eat a few meals some of the days, so accustomed am I to having kids at home begging me for lunch and reminding me humans need food), I lost myself in my inner worlds.

For me, writing is an obsession.

If I let myself, I would be a workaholic. I have trouble pulling myself away from my work because it’s an obsession. It’s also much more than that.

But before I get into that, I must acknowledge: I know writing is not an obsession for everybody. It takes hard work and dedication to show up to the page every day. Many might even consider me lucky——though anything taken to the extreme can be problematic.

My interest in writing goes deep. It started early, when I was very young and fell in love with stories. I loved the way stories could take me away from the world I inhabited. I couldn’t wait to bury myself in a book and spend time in other places, with other people, living lives I’d probably never live myself. And it didn’t take long for me to decide I wanted to create those places and people and lives in the stories I’d write.

I consider what I do my purpose. Telling stories is what I was made to do.

Many of us feel that way. Maybe even most of us. Why else would we come back to the relentless blank page?

But there’s something else I’ve noticed in my years of pursuing this dream, and it’s this:

Writing does the most work on us. It changes us for the better.

Writing centers us.

When I write, I become a calmer person. I make sense of my chaotic world. I dream and imagine and explore. I quiet all the worries and anxieties that pursue me. Writing is my stillness and my solitude. It allows me to take a breath, reconnect with myself, and remember all the good that’s in my life (and there’s so much!).

I remember a woman laughing at me, way back at the beginning of my writing career, when I confessed to a room full of people that writing made me a better mother. My children were very young at the time. And so needy. Writing, I felt, helped me balance that neediness with seeing to my own needs, thereby making me a better mother.

The woman made a beeline for me after the event was done. She said, “If you want to write and work, fine. But call it what it is—you just want to write and work. It doesn’t make you a better mother.”

I was taken aback, because how could she know? The days I managed […]

Read More

There’s a band from Chicago called Wilco that I’ve been in love with my entire adult life. If you’ve heard them, you know what I mean. If you haven’t, maybe you’ve heard their music pop up in movies and TV shows, like Ted Lasso and, most recently, The Bear.

Back on June 20th, my wife and I gave our kids some pizza and permission to stream as many movies as they wanted and made the trip from Baltimore down 1-95 to see Wilco perform at an outdoor amphitheater in Virginia. They were, as always, terrific.

Early on in the set—their seventh song, but who’s counting?—the band played “I Am Trying to Break Your Heart,” a hit off their album Yankee Hotel Foxtrot. Generally, most Wilco songs are fairly straightforward. Much of IATTBYH, though, at least lyrically speaking, makes very little sense, and that’s a good thing. Here’s how it starts:

I am an American aquarium drinker

I assassin down the avenue

I’m hiding out in the big city blinking

What was I thinking when I let go of you?

You get three lines of poetry here—lovely and random. But then, my god, that fourth line. It’s crystal clear, pitch perfect, and, in lead singer Jeff Tweedy’s voice, it’s an emotional stunner. My eyes welled up as he sang those words in Virginia, and, embarrassingly, they’re welling up a little now as I write this. Damn you, Jeff!

My point—along with humble bragging about getting to see a sick concert—is that emotion is what makes art so powerful, and, as writers, it’s our job to deliver that emotion as much as we can. Here are some tips for doing that and for turning up the volume on all those feelings in your work.

Hit ‘Em in the Heart, Not the Head

As we know, reading and writing are intellectual exercises, practically by definition. But reading and writing are very much emotional exercises, too. Think about the last few books you read that you didn’t particularly care for. Technically, on a sentence-to-sentence level, those books may have been written well and drafted with great effort and care by professionals. I’m willing to bet, though, that in most cases the authors of those books failed to create characters with whom you connected emotionally or failed to create situations or scenes that made you feel something—at least something worthwhile.

So many of the words and sentences we write in longform pieces—fiction or nonfiction—are the equivalent of nuts and bolts in construction. We’re presenting necessary information. We’re orienting our readers in time and space. We’re erecting the metal posts required to keep our plots from crumbling to the ground. While all of that is important and necessary, never forget that there will be an actual person reading it. As you write and revise, constantly ask yourself: Is this making the reader think or feel? Good writing can do both, of course, just as good writing can be intellectual as hell. But if you’re not skewing toward emotional relevance your reader’s attention will eventually drift.

Be Revealing with Your Characters

Your characters need to want things. Duh. Their motivations will propel the engine that drives your plot. However, your characters are also human—let’s assume—and that means that they love some things, too. […]

Read MoreDearest Gentle Readers,

Hopefully those of you who enjoy televised programming have had the chance to finish the third season of Bridgerton on Netflix. While I always try to relax the writer part of my brain when I read or watch other people’s writing, it can be tough! Inspirations, observations and lessons keep sneaking through. So while I primarily enjoyed Penelope and Colin’s story for its own sake, I also noticed a few things that I felt might be useful for my own writing — and maybe yours?

Warning: spoilers for the entirety of Bridgerton Season 3 abound below!

The end isn’t always the end.

At the halfway point of the season, the key couple declared themselves to each other and the hero proposed marriage to the heroine. End of story, right? Nope, raising the stakes — because once Colin swore his love for Penelope, she had all the more reason to fear the revelation of her identity as Lady Whistledown because she might lose Colin as a result. You don’t want to give your characters everything they want early in the story, but neither do you want to hold off all the major action for the story’s climax. Ebbing and flowing action does wonders.

Villains need reasons.

One of my favorite writing guidelines (I won’t say rules) is that the villain is the hero of his own story, and it applies here to Cressida Cowper. She does a bunch of lousy things, endangering our favorite characters with her machinations from the first episode of the season to the last. Yet the show is careful to humanize her and show why she does what she does, struggling to escape a life she hates. No one sets out to write a cardboard villain, but many of them end up that way if the writer doesn’t do the work of giving them a complete set of circumstances, goals and desires. Sorry about your aunt, Cressida.

Use your cast.

With a sprawling cast like Season 3’s and the way that Bridgerton is structured, we spend a lot of time checking in on characters who’ve already had their day in the sun (Kate and Anthony) and future featured players (hey there Francesca), even if their plotlines sometimes feel like so much wheel-spinning (that was a lot of Benedict, in every sense). You may or may not have a cast this sprawling in your writing — my historical fiction doesn’t, my epic fantasy absolutely does — but when you do, it’s important to ask yourself a key question whenever you need a character to provide an action: can someone the audience already knows do this? We had to meet a lot of new people, but the action also got some goosing at key times from Lady Danbury, the Queen, and even Penelope’s mom, Lady Featherington. It’s going to be easier for your readers to keep track of characters you’ve already introduced, so if you’re going to bring in someone new, make sure they’re essential — and make them memorable.

Do you experience other people’s writing primarily as a writer, or are you able to turn off that part of your brain and just enjoy? Have additional takeaways after watching season […]

Read More

The protagonist in my second novel is a sixteen-year-old boy. Since the book was published in March 2023, the question I’ve been asked most frequently by readers and reviewers, especially men, is how I was able to write a character so drastically different from myself who seems like he could be a real person.

When I was first asked this question, I didn’t have a good answer. I just created a character that felt real to me, I’d say. But after being asked multiple times, I decided to put some thought into it. The tips below are things I regularly do that have helped me make my fictional characters feel like people you might actually meet.

I observe people carefully.

Because I’m an introvert, I’ve always spent a lot of time watching other people, both friends and strangers, often without realizing it. Doing this has allowed me to pick up on subtle traits and habits individual people have, such as the way someone ties their shoes (lefties tend to use the “rabbit ear” method), or the things some people do when they feel stressed or nervous, like repeatedly adjusting their eyeglasses.

Sometimes these traits can be age-specific or more commonly seen in people of a certain gender, culture, or ethnicity. After a lifetime of observing people in my own family, I’ve come to believe that many of these behaviors are inherited or at least “contagious.”

Also important is noticing the way people are dressed. A habitual runner might still have his sweatsuit and sneakers on when he goes grocery shopping. A trial lawyer might always be wearing a tailored suit when she picks her kids up at school. Someone who’s wealthy, or trying to appear so, might carry an expensive handbag when wearing an otherwise unremarkable outfit.

When I sit down with my laptop to work on a novel or story, I think about the characters and what similarities they might have to actual people I know or have seen, and I try to incorporate some of their traits into my characters’ personalities.

I listen to the way people talk.

Because dialogue, both spoken and internal, is an essential part of any fictional story, paying attention to the way actual people talk is important. Someone’s accent, even a complete stranger’s, can often tell you volumes about that person whether you speak to them or not.

Because I have lived in a city that has a large population of immigrants from around the world for the last twenty-plus years, I’ve gotten good at discerning accents. I can tell the difference between a native Spanish speaker from Puerto Rico and one from the Dominican Republic, for example, by their accents when they’re speaking English.

One of the most interesting things about paying close attention to the way people speak is when I hear someone who is trying to hide their accent. I first picked up on this after meeting the wife of a colleague of my husband’s who was from Alabama. To a casual listener, she might not have seemed to have had any accent at all, but there were subtle markers in the way she pronounced certain […]

Read MoreMy blood pressure is rising, as I sit here pondering what has dominated my writing life lately and what, therefore, I should write my WU article about today. My blood pressure skyrockets as I wonder when and if I’m EVER going to get more words in on my WIP. And then I am struck with the answer: procrastination! For weeks, I’ve been sitting down (the ol’ butt-in-chair) and attempting to write, but instead, I look up recipes and write “to do” lists and take care of the dozens of writerly admin chores waiting for me in my inbox. I write a few sentences and delete them, gaze at my outline, and then I clean the kitchen and run errands. I do everything but put actual words on paper.

I have a deadline, you see, around the holidays at the end of the year, and I’m trying not to panic as I stare at my 28,000 word count that has remained the same for weeks and weeks. I know it’s possible to crank out a draft by December, but given the kind of writer I am and the amount of drafts I typically do, I should be on my third draft already, layering, layering, layering. Instead, I’m stewing over the plot, moving commas around, cutting pieces and filling in others, waiting to hear back from experts on a few historical details. Worst of all, I’m still trying to figure out how I want these details to drive the B story of the book. What is the B story?! I just don’t know how this will all come together. I don’t know if my heroine’s story is a worthy tale, or if I’m using the best structure, or if I pull this one off!

In the midst of all of these “I don’t knows,” I’m practicing some serious self-loathing and above all – procrastination. Ahh, procrastination. We are old friends, but I must admit, it has been quite a while since I have seen thee. I’m a “put in the work a little every day” kind of girl, at least since I graduated college many moons ago. But it seems that right now, the young, dithering, procrastinating Heather of yore is back.

WHY OH WHY IS THIS ONE FEELING SO HARD?

So you see, I’m actually glad I’m writing this post today because I could use a little self-examination to help get me going again. This is what I’ve come up with:

The Problem

The Solution

When our procrastination is at an all-time high, we need to reframe our thinking, alter our typical routines, and make room for an evolving writing process to set ourselves up for success. Here’s how.

Time constraints & Accountability. When I am at my most distracted, I have discovered that setting a timer for thirty minutes – in particular with a writer friend that I can sprint with – works miracles. Suddenly I have accountability! Not just that, I have a literal ticking clock! The pressure is on […]

Read Morephoto adapted / Horia Varlan

Early reading influences can have a powerful effect on a future writer. In her May post, In Praise of Passionate Persistence, WU contributor Kristin Hacken South shared an early influence of hers, The Phantom Tollbooth. Her post inspired such nostalgia in me that I wanted to play, too.

When I thought it through, though, the story that offered up the most useful and practical lessons wasn’t one of my favorites. Yet its impact was memorable, and only in retrospect have I appreciated its lessons about story and the writing life.

It began:

In the old days, no one but a king could have a dog for a pet.

Published in 1958, written by Benjamin Elkin, and illustrated by Katherine Evans, it was called The Big Jump. If you’re interested, Grandpa Brian will flip the pages and read it aloud to you at this link. The following plot summary contains spoilers.

When the king walked his dogs, all the boys and girls came out to watch. One day a pup ran away from the king and straight toward a boy named Ben. He told it to go back—he didn’t want to get in trouble—but the pup licked his hand. The king took note.

Ben wanted the dog badly, but alas, he was not a king. Until the king told him, he didn’t even know that to be a king, one had to be able to do The Big Jump. Ben asked what The Big Jump was but the King was gone—and reappeared on top of his palace. If Ben could jump that high he couldn’t be a king, but he could have the dog. For now, he could keep the pup for one day.

At home, Ben stacked wooden crates and practiced jumping. They were nowhere near as high as the palace, and yet he failed, over and over. Then he had the idea to vault with a stick, and was able to jump to the top of four boxes—but no more.

The pup jumped onto the first box, then the second, then the third, and then sat on top of the stack. Ben knew how to jump to the top of the palace. After he demonstrated for the King, the other children mocked him, saying that they could all do it that way. But the King pointed out that they could only do it now because Ben had showed them how. He won the pup.

Here are 8 of this story’s metaphorical lessons for writers.

Read More

In my last essay for Writer Unboxed, I made a case for not sharing early drafts. For ignoring other voices, especially critical ones, and blocking out the constant noise of everyday life to protect space for the imagination. I encouraged fellow writers, especially newer ones, to listen to the tentative, inchoate voice within. In this essay, I pitch another approach to the writing craft: reading. Finding one’s voice as an author can only happen when we unplug, turn off our phones, shut down our screens, and not just write, but read. Reading is my number one recommendation for how to improve as a writer.

In today’s cacophonous world the goal of sustained reading is harder to achieve than ever and, I would argue, more important. Before the pandemic and farther back, before constant iPhone use, I read fifty to sixty books a year, mostly novels. Post-pandemic, I can’t seem to finish thirty to forty. Those numbers might still sound large, but not if you consider that novel writing is my business. To write good novels, I need to read good novels, and sometimes bad ones. A key part of the practice of becoming a serious writer is to be a serious reader.

The reality of a waning attention span, though, looms over my, and perhaps your, literary life. Recent studies suggest the average undivided attention span for adults today has shrunk to just eight seconds. Eight seconds! Against a statistic like that, novels haven’t got a prayer. More and more people are listening to audio books as a cheat against distraction. You can drive, wash dishes, and walk the dog all while narration reaches some other part of the brain. Listening to a novel may require less concentration than reading a text, but I think still ‘counts’ as reading.

Still, there’s nothing as rewarding and engrossing as deep immersion in a book. It’s a complex experience that can be magical, taking a reader out of the present moment and their own body and into another world. Some people find listening to music transporting. Or watching a film. To my mind, those experiences don’t require the same meeting of imaginations that takes place between a reader and a writer.

But what does this have to do with crafting our own work? I’d say everything. As Margot Livesey has put it, we must “learn to read as a writer, to search out that hidden machinery, which it is the business of art to conceal and the business of the apprentice to comprehend.” As we absorb the written words of others, we not only learn about structure, character development, and all the other choices a writer must make, we also develop a crucial ear for language. So much of good writing is the shape and rhythm of sentences. By reading well-structured syntax, we internalize it and more easily make it our own. Familiarity with the vast array of written voices paradoxically offers a better chance to be innovative and original. How else to know what’s already been done so we don’t repeat it–or are at least aware when we do? In reading broadly, we position ourselves within the literary conversation that’s been carrying on for not just years, but generations.

So, what sorts of […]

Read MoreIn my last post, I talked about brainwaves and how they tie to intuitive writing. Alpha and Theta are the two brainwaves most conducive for deep creative work. Alpha is when our bodies and minds are in a relaxed, meditative state, and Theta generally occurs in the twilight of sleep when we’re about to start dreaming.

Stories are curated dreams captured on paper. So how can we quickly get into the proper brainwaves to daydream whenever we want—even in a noisy house or during a stressful day?

Sound

One extremely effective way is using sound. Sound has powerful effects on brainwaves, which is why drums, flutes, bells, and singing bowls are often used for transcendental meditation. The repetitive sound-wave from these instruments cause the mind to go into a Theta state.

So if you need to get in the zone quickly, and stay there, find an instrumental song that speaks to you and your story, something that can play almost unnoticed in the background. Then set it to repeat. The first time you play it looped, focus on getting into the zone and having a productive writing session. On the next day, use the same song. If you do this enough times, your mind will immediately enter Alpha state when the music begins to play. I find this very effective when I’m under a tight deadline and every moment at the keyboard has to count.

“Zen” Activities

When you step away from the keyboard, there are simple daily activities that automatically trigger an Alpha state. What if we take advantage of those times and use them to write?

Alpha activities include:

With our intention, we can turn these activities into effective writing times. You may not be at the keyboard (and perhaps worried you’re not) but it’s all about quality versus quantity. Visualizing your story while you’re doing something repetitive or relaxing often brings perfect answers to story problems and delivers memorable lines and dialogue.

So go into the activity knowing it will be writing time. Visually compose scenes in your head. If you drift off topic, that’s fine, just bring your focus back. Have a notebook or your phone nearby to dictate lines, ideas, or dialogue. Hang a “Do Not Disturb” sign to the rest of the word and work deep.

Art

Another Alpha-inducing activity I suggest trying is making a piece of art in solitude.

Think about something you could make that ties to your story. Go to Michaels or Hobby Lobby and browse for inspiration. Then schedule some alone time to unwind with your paints or putty and mull over your story. You’ll be surprised what inspiration strikes–because you’ve gone into a deep Alpha state. (I started practicing this with my second novel. The fun part is whatever I make I usually end up giving away at book events.)

Another idea is to jump on Pinterest to find images thematically tied to your story and simply gaze at them. Allow your mind to quiet and deliver whatever thoughts the artwork evokes. I make visual inspiration boards […]

Read MoreGetting a book-length manuscript to the finish line, polishing it, and launching it into the world require a single-minded focus–and a community of writers like this one to believe for us when the publishing journey gets rough. As a first-time author, I didn’t know what to expect. For a long time, no one was waiting for The Kindest Lie, so I had many years to stop and start, to play, and to delight in the fairy dust that is sometimes (if you’re lucky) sprinkled over a shiny debut. Then I signed a contract with William Morrow/HarperCollins for a second book, People of Means, which releases in February 2025. Anxiety took over, and I wondered if I could do it again. The second time around as an author isn’t easier, but I’m wiser and better prepared.

Here’s what I’ve learned:

You never master the craft. The book isn’t ready when you think it is.

After at least three years of writing workshops and several drafts of my first novel, I thought it was in good shape to send to agents in my quest for representation. Not so much. Following close to 100 rejections, I took a step back for a year-and-a-half and workshopped excerpts of my book at the Tin House Summer Novel Workshop and Kimbilio Fiction for African American writers. Then I engaged five writer friends to beta read for me. Only then did I get two offers of representation and choose the wonderful Danielle Bukowski of Sterling Lord Literistic. Subsequently, my fabulous William Morrow editor, Liz Stein, took my manuscript through three grueling rounds of edits.

When I began writing my second novel, I felt pretty confident that I knew what I was doing since I had done it once. Wrong! After sending early pages to Liz, I learned that the book needed a lot of work: structure, character development, relationships, motivations, and more. Under contract with a tight deadline, I didn’t have time to solicit beta readers or workshop the book. With Liz asking me lots of probing questions and helping me dig deeper, I revised multiple times until finally the book on the page came close to matching the vision in my head.

Life doesn’t pause for the publication of a novel. Don’t be afraid to ask for what you need.

I have a demanding day job leading corporate and internal communications for a large health care organization. Early in my writing days of my second novel, I got promoted to a director role and began leading a small team. The day job supports my writing habit, so no complaints there. But suddenly, I had more responsibilities, which made my writing time even more precious.

Soon after, my mother began to repeat the same stories and mail greeting cards more than once for the same occasion. A neurologist diagnosed her with Alzheimer’s, and I took on the role of caregiver. With a deadline for book two looming, I sold my mother’s house and moved her into a senior living community and helped her navigate this monumental life change. I desperately wanted to do it all, but I couldn’t. As a former journalist, I’m a stickler for deadlines but I knew I couldn’t meet this one. With great trepidation, I asked my […]

Read More

“What do we say about coincidences? The universe is rarely so lazy.” –

Sherlock, S3 Episode 2

Writing is a leap of faith, a nail-bitingly risky foray into the unknown. We’re adventurers following strange paths, never certain whether we’ll find our way or what type of reception we can expect if we finally arrive. Is it any wonder, then, that we look for encouragement along the journey?

Sometimes that means stumbling across it in unexpected places. When I was writing my last book, which features Peter Pan and talks about stars, I found both everywhere. Peter Pan figurines in odd little gift shops and tattoos of the boy who wouldn’t grow up inked on random passersby; stars scribbled on bathroom stall doors and folded out of origami paper. These signs showed up at odd times and hours, often when I was in despair about ever pulling the book together, and lifted my mood enough to carry on.

I’ve since started a new project, and to my delight the magic continues. I’ve found symbols that represent my new story by the side of the road when I’ve been out jogging, on record covers in second-hand stores, and once, most memorably, in a flower shop in Salem, Massachusetts (home of the WU Unconference).

These little signs never fail to surprise and enchant me. It’s as if the universe is whispering in my ear, telling me I’m on the right path, that home is just around the corner if I’m brave enough to persist.

I don’t really believe this, of course. Instead, I think these “signs’”are like the pink elephant theory—once you’re thinking about something, it’s almost impossible to stop. These physical displays are just my subconscious working overtime, struggling to find patterns and story threads wherever I look.

But still, they make me happy. And I try to turn them to my advantage by asking myself two questions when they appear:

The first is simply: How does this item relate to its setting and can the juxtaposition between the two help me think about my writing in a different way?

For example, during the writing process for my last book, I found a tiny golden star on a park bench. The juxtaposition between the star—shiny and bright—and the park bench—worn and dingy—had me considering what would happen if magic entered the real world from another place. Would the magic somehow be tarnished, or would it stay bright? These thoughts eventually helped me form the “rules for magic” in my story.

The second question I ask is: What does this mean? I’m not necessarily looking for a universal truth – although if I can suss one out, that’s a bonus. Instead, I’m thinking about what the item’s story is in relation to the person or event that placed it there.

The star mentioned above could be a trinket abandoned by a child (leading me to think about the fleetingness of childhood and the emotions that arise from that) or it could have been deliberately placed on the bench in memory of a person or relationship, or any number of other scenarios. What interests me most is whether any of these resonate with what I’m working on, […]

Read More

If you attended the opening night of last fall’s UnCon, you heard me tell of the career struggles and dismay I experienced in the wake of my 2022 novel’s release, and how I dug my way out of that hole by embracing the theme Therese Walsh had announced for conference: All In. Today’s post revisits that struggle, along with what came next.

*

Two years ago, for the second time in my 15-year, seven-novel writing career, an ineffective marketing plan led to anemic sales—which meant that I once again found myself at the bottom of a steep hill with a heavy rock to push if I was going to continue to have a fiction-writing career (where each advance, as well as retailer orders, are determined by the previous book’s sales). Did I want to keep writing novels and publishing them traditionally? I stood there looking up the hill. I nudged the rock to gauge its weight. I’d been writing fiction full-time since 2007. I knew exactly what it was going to take to push that rock up that hill again. I thought, Fuck it.

Yet, even as I lamented all the ways things hadn’t gone well and all the ways the industry is stupid, my brain just kept doing what it’s been doing since the days when Captain and Tennille ruled the radio stations: noticing things and people, wondering about them, fitting them into scenarios and then playing with those ideas as if they’re Rubik’s Cubes. IT…JUST…HAPPENS, even when I don’t necessarily want it to. So, what I needed was something to spark not the creativity for producing fiction, of which I have plenty, but rather the ambition to persevere despite the aggravations.

Perseverance is fueled by ambition, of one kind or another.

The spark eventually arrived in the form of a new story idea that, the more I explored it, felt like I’d found lightning in a bottle. I celebrated the return of those old familiar loves, Impatience and Excitement. If I could figure out how to transmute my idea into words on a page, I might have a rock worth pushing. I also recognized that if the book-to-be was going to get its best chance in the world, I needed to cancel my existing contract and find a publishing home that would be a better fit for my work. Doing this is not fun. But sometimes it’s necessary. I made a big commitment to clearing the decks and starting fresh. I went all in.

The universe sometimes seems to reward bold actions and difficult choices, and this was one of those times: soon after I made the big commitment, Amy Einhorn, an editor/publisher I’d admired from my earliest fiction-writing days, left Holt to restart the fiction line at Crown using a publishing model that promises careful attention to a small number of titles each year. It sounded like the perfect new home for me and the new book-to-be—an ambitious novel set in the chaotic wake of WW1 and inspired by my own family’s history. I wrote a detailed proposal and some sample pages, sent them to Amy (through my agent), we had a great conversation, and she offered me a contract, which I accepted. Then we lived happily […]

Read More‘There were trees here once, in another age,’ Mother Rowan said. ‘Great, wonderful trees something like the one you called the Ancestor. Such things they witnessed in their long lives: the fall of kings, the deeds of heroes, the passing away of tribes and the grief of survivors. Courage and cowardice; justice and tyranny; love and hate. No wonder old trees are so full of wisdom.’

That’s a quote from my work in progress, folks. Odd way to start a WU post, you may think. How can the wisdom of trees shed light on the craft or business of writing? Well, this is a post about storytelling, and the protagonist of my novel is a storyteller who cares very much for the environment, and in particular, the preservation of forests. And it’s a post about writing in an age when trees are often not accorded their due respect. In some parts of the world, those in authority understand how vital the survival of trees is in the struggle to protect our planet. In other parts, tragically, those with the power to act don’t understand this—or don’t care—even when it’s playing out right before their eyes. Here in Western Australia we’ve had virtually no rain in the last 7 months (late spring until end of autumn.) This has been the hottest May since records began. And our trees are dying. Street trees in the cities and suburbs; forest trees further away. Not only young trees, but mature ones and ancient, celebrated ones. Habitat for wildlife. Shade for humans. Breath for the earth.

A step back into folklore, fairy tale and legend now. Trees have an important place in traditional storytelling. In the days of tales told around the fire, folk most likely understood the importance of forests without knowing the science behind it (I’ll refrain from a harsh judgement of today’s humans here.) People in those times knew trees offered shelter from the cold, shade from the heat, food, fuel, somewhere to hide from your enemies. No doubt tree deities or spirits were duly thanked for these gifts. As for storytelling, where would the Robin Hood legend be without Sherwood Forest, where you can still see Robin’s ancient oak? In Irish mythology, a lone hawthorn tree was believed to be a portal between the human world and the Otherworld, a place where a person might communicate with that realm of magic and seek wisdom. And there’s the Ogham alphabet, thought to have been used by Irish druids back in the day, in which each letter relates to a tree species with its associated symbolism. These signs were inscribed on stones or the trunks of trees, or sometimes, it’s said, shown subtly with the fingers as a means of covert communication – not so much spelling out words as using a coded sign language. Handy in an awkward business meeting between, say, druid advisers to warring kings.

Can a tree be wise? Can writers learn from that wisdom? I think so. Trees send their roots deep down. They grow tall. They spread their branches wide. Some can live for many, many times a human lifespan. Readers may remember my previous posts mentioning the ancient yews at Crom […]

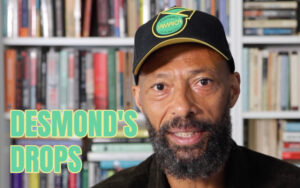

Read MoreWelcome to a new edition of Desmond’s Drops!

This month, enjoy three new drops about Blake Snyder’s genres from his classic book, Save the Cat!

Email subscribers, please click directly to staging-writerunboxed.kinsta.cloud to view, or visit all of Demond’s Drops on YouTube.

Look for more of Desmond’s Drops in JULY! And be sure to visit on JUNE 2nd to read a Take Five interview with Desmond and celebrate along with us as he launches his second novel, BETTER MUST COME!

Have your own bit of wisdom to share? Drop it in comments. Read More

photo adapted / Horia Varlan

Thanks to the 24/7 information kiosk that is the internet, anyone with a smart phone can now become a lay doctor. This can be handy if you wake up in the middle of the night with a stabbing pain and learn that the burst appendix you feared was probably just gas. But for a while now, I’ve been wondering if immediate access to all things medical is always good news for novelists.

Back before it only took a tap of the finger to paste a celebrity photo onto a Pinterest board or borrow a bio from a known sociopath, writers imagined their characters into existence. If that character’s specific story included a mental or physical health challenge, instead of cruising the ’net for a diagnosis, the writer might wonder, If something in a man’s brain made him go blind, how might that test his wife’s assertion that her plastic surgeries were meant to please him? In that story, the husband’s localized headaches and blurred vision might be convincing enough. Consider the law of diminishing returns: these days, a writer can spend hours if not days of their precious writing time googling whether shrapnel from the Vietnam War could migrate slowly through the brain to cause similar damage decades later. (If that sounds oddly specific, um, well, I have no idea why).

I’m not convinced we need to do that.

Prioritizing the protagonist’s character and her story before doing research is still a solid approach. In the May/June issue of Writer’s Digest magazine, author Alyssa Cole spoke about her process creating the lead character for her newest thriller, One of Us Knows, who is the host of a “system”—the group of personalities formed when an individual has dissociative identity disorder. Cole first came up with the basic story idea: “What happens when the main person who is causing trouble is also the one who has to get them out of trouble?” She says, “I didn’t want to read someone’s story and then be like, Oh, let me make a story based on this thing.” Only then did Cole check primary sources to ensure that she was “accurate within reason and respectful.”

Put story first

For my debut novel, I decided that a formal diagnosis for my protagonist would fail to communicate one of the most frustrating realities in treating mental illness: it’s the person who doesn’t think they have a problem that must seek the diagnosis. The words “body dysmorphia” also would have ripped the heart from my story. It was her disordered thinking about her body that kept her butting up against the unwanted consequences that pressured her to change. I chose differently for a major secondary character. Her known cystic fibrosis diagnosis averted any “medical mystery” that might upend focus on the story I wanted to tell, of how two woman of the same age—one with a strong body but a weak spirit, the other with a hearty spirit but a weak body—might influence each other.

Impaired characters who remain undiagnosed are common in literature. Since 1843, when Edgar Allan Poe’s The Tell-Tale Heart was published, it has been critics—not the text of the short story itself—that spoke of the […]

Read More