Fiction therapy

Stonewall Inn – Jun 21, 2019. Photo by John J Kelley

Fifty years ago, when I was but a toddler in a bayou town along the Florida Panhandle, an uprising at a nondescript Manhattan bar changed my life. On Jun 28, 1969, patrons of Stonewall Inn, a hangout for some of the city’s most marginalized populations did the unexpected, striking back rather than complying when police raided the establishment. For reasons even participants could never fully explain, frustration and anger from years of ongoing harassment suddenly erupted. Over the course of several hours, what began as a clumsy operation to clear the bar grew into an open rebellion, drawing hundreds to the streets of Greenwich Village in protest. When the dust settled two days later, the queer community found an instant rallying point which would propel its members from the closet to the front lines of an ongoing civil rights movement.

But public incidents, no matter how epic they may feel in retrospect, rarely change any given individual’s mind or touch one’s heart. As a child of the Deep South, I wouldn’t even hear of Stonewall until two decades later. So while I am grateful for their act of defiance all those years ago, and for the many struggles – and successes – that followed, stories from Stonewall were not key to my personal evolution as a gay man, at least not emotionally. That I owe to the talents of a writer on the opposite coast a few years after the events of 1969. That man is Armistead Maupin, and the weekly serial he crafted for readers of the Pacific Sun and later the San Francisco Chronicle became the beloved Tales of the City book series.

CC BY-SA 3.0 – Stonewall Inn 1969, Diana Davies, copyright owned by New York Public Library

Coming to terms with my sexuality while serving as an Air Force officer, Tales offered a glimpse of a world in which being gay need not define me, dictate some hopeless fate or dominate my thoughts as it so often did at the time (the closet can be like that). Maupin’s characters were funny and flawed and imminently human, living their fullest lives with zeal. And though the narrative was as breezy as a beach read, when it dove into deep emotion, the words rang true, offering profound insights on the human condition. In ways I didn’t realize at the time, his stories gave me a blueprint for how life could operate if I opened my heart and let myself breathe. In essence, his writings gave me the freedom to be myself.

Great stories can do that. They open a window to a broader world and provide a microscope for examining our innermost feelings. Now that I am a writer as well, one still striving to achieve Maupin’s skill at developing a compelling cast of characters with tightly woven arcs, I have a theory that every writer has an “origin source,” the read that first opened their eyes to who they are or aspire to be, and which act as touchstones through the years. To explore my premise […]

Read MoreJesper Sehested via Flickr Creative Commons

Which do you enjoy more . . . revising or writing (first-drafting)? Just like the universal plotter vs. pantser question, this is one of the most enduring discussions among writers I know. Maybe you’re in one camp more than the other? Or maybe you’re somewhere in between.

Until recently, and without hesitation, I’d have answered I was squarely on Team Writing. But lately I’ve been thinking differently about revision. Not that it’s an either-or versus writing, but that there’s a closer link between revising and writing—a different way of looking at the relationship. But not in the obvious way—of making a given manuscript better—but as a writing tool. As a way to enrich the writing process, to reinvigorate your approach to writing.

Let me explain. I used to love the thrill of the blank page, of getting lost in a new story. That was before I hit the slump of all writing slumps, which I’ve written about here and here. I’d lost the real passion for my writing projects, and I was never able to get anywhere near that magical “writing zone.”

Go Team Revision!

As part of my attempt to get my writing back on track, I turned to revising a novel I wrote four years ago. My thought was that I already had a completed body of work, and by starting with that, I could avoid what had become a fear of the blank page. A fear of writing. It didn’t hurt that I believed the novel was worthy of revision—I’d gotten good feedback from an agent in the form of an R & R (Revise & Resubmit)—which she ultimately passed on. But I did have her extensive notes.

Neil Gaiman said, “. . . Put [the story] in a drawer and write other things. When you’re ready, pick it up and read it, as if you’ve never read it before. If there are things you aren’t satisfied with as a reader, go in and fix them as a writer: that’s revision.”

That’s what I did. At the beginning the process was frustrating. I had some of the same problems I felt with writing new material—I was afraid I just couldn’t do it. I knew that the second half of the book was the most problematic with both plot issues and a weak character arc, but I wasn’t quite sure how to fix the problems. I consulted an editor. She allowed me to see the story through her eyes, and that helped, but what really swayed me into Team Revise was that I’d been away from the story for a long time. I was able to read it more as a reader with less emotional resistance to making changes—I was able to be more objective—and for the past three months I’ve been deep in those revisions.

A lot changed on the way to “THE END 2.0.” For instance . . . the end of the story. It didn’t change completely, but it changed enough to offer the main character more transformation and growth. In addition, some secondary characters took on larger roles, some smaller, one disappeared altogether. I added more description and breathing room; I took out unnecessary […]

Read MoreBest-selling thriller writer, Ian Rankin, has been writing professionally since the mid-1980s. He’s written close to 30 novels. He pretty much writes a book a year. But, at a certain point in his drafting process, usually somewhere at the end of the first month, he is struck by, what he calls, ‘the fear.’ He is convinced that all the work he’s done in that month has been a waste of time, that this new book won’t be any good.

When he mentions this to his wife, she usually asks, ‘Are you on page 65?’ He thinks about it, and yes, he is. It’s then he realizes that he goes through this phase with every novel, always at the same point. Always around page 65.

Many writers, if not all, experience this kind of doubt about their work at some stage. And, since writing is such a lonely profession, they don’t all have someone with whom they can share their frustrations.

I feel privileged, in my work as an editor, that authors confide their fears in me. Sometimes they just need someone who can give them feedback, someone with experience who can reassure them that their work is worth pursuing after all and they’re not wasting their time. Someone who can help them get past their page 65.

But not everyone has the time, the inclination, or, let’s face it, the money to seek reassurance from an editor. That doesn’t mean you have to suffer alone. Below are some techniques that can help authors deal with that inner critic and get back to writing.

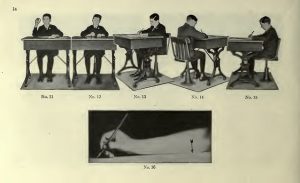

Read MoreEarly in the fall of 1994, I had a terrible realization: I did not know how to write.

This was problematic as I, fresh out of college, had been hired to teach high school English. In other words, I was supposed to teach something I couldn’t do myself.

But how had I never realized I couldn’t write? Worse, how was it possible that not one of my high school English teachers, not one of my college professors, had taught me how to write?

I promptly began working my way through the Ten Stages of Writing-related Grief: Shock, Betrayal, Anger, Humiliation, Chocolate, Half-hearted Acceptance, Chocolate, Despair, A Decent Amount of Acceptance. And finally, Peace.

I hunkered down in Shock and Betrayal for quite some time, wondering how this could have happened. As I hunkered, I soothed myself with chocolate chips and episodes of Seinfeld.

True, my high school English teachers were crummy and weary. They assigned writing, but assigning writing, I finally understood, was not the same as teaching writing.

My 12th grade English teacher was one of those old school, sweet-but-tough-but-good teachers who cracked her feedback whip with lovely, looping, curving, cursive penmanship.

A few decades earlier, she might have whipped me into shape, but by the time I became her student, she was getting along in her years. And losing her filter. As well as her ability to focus. On several occasions, she’d pause herself mid-lecture, tilt one ear to the ceiling, and–I am not kidding–shush us so she could listen to God. This was public school, but God, they say, is everywhere, including in AP English Lit class. So He’d interrupt our class, our teacher would listen thoughtfully, after which she’d take time to relay His messages to us. By then, class would basically be over, and we’d have gone another day without learning how to write. Because God is everywhere.

In college things were no better. Pursuing a degree as an English major, I found myself surrounded by tough and salty professors, none of whom (I see only with hindsight) spent time teaching us to write. Instead, the gnome-ish Medieval English Literature professor nearly daily recited The Canterbury Tales in a wobbly, sing-songy voice that indeed sounded Chaucerian.

In Theories of Deconstruction, the goatee’d professor spouted confusing things about Jacques Derrida’s theories (pronouncing Derrida like “Dairy-daaaahhh”). There was no writing instruction in that class either. Nor any in my Shakespeare class, nor my African American Lit class, nor my American Lit class. Nor, nor, nor. Zero, zero, zero.

It wasn’t until I stepped into my own classroom, charged with teaching 155 students how to write essays, that I realized the magnitude of this issue. What would I teach if I didn’t know how to teach writing?

Dairy-daaaahhh, the goatee’d professor whispered from the depths of my memory.

The Medieval Lit gnome then chimed in, warbling, And gladly wolde he lerne, and gladly teche.

I tilted my head to the ceiling. God was silent.

I had no wisdom to share, no role model or mentor to use as my guide. But I needed to pay rent, and I needed to […]

Read MoreWorking out what your characters’ goals are will help you plan your plotline and develop engaging, motivated characters your readers will love to follow.

Your characters need goals to get them to the next page, and then the next, and on until the end. They need to be going somewhere, trying to achieve something. That will make them the kinds of characters readers will want to spend time with, maybe even for a few hundred pages.

Readers will want to know if your characters achieve those goals, and if they will overcome the inevitable obstacles (you put) in their way. Sometimes they will, sometimes they won’t. They will have small goals that they can achieve (or not) within a couple of pages, and they will have those overarching goals that will take your heroes right through to the end.

Even Oblomov, the man who stayed in bed for most of the story, had a goal: he wanted to stay in bed. And he worked hard to do it. That was pretty much his story.

Your characters’ goals are therefore essential for determining your plot. Work out the goals and you’ll go a long way to having a plot. And, if you already have a basic plot, you can develop it in greater detail by working out what your characters’ goals will be along the way.

Read Morehttps://wallpapercave.com/dark-sea-wallpaper

A friend of mine recently asked me why I write. She found she couldn’t answer the question herself, not anymore. She’d lost the love, and she was hoping something I’d say, as well as the other writers around her, would trigger an awakening in her. She wanted to find her path back to the career about which she had once been so passionate. I think we all go through this at one time or other, when life at home becomes difficult, or when everything in your writing career goes wrong. The rejections become unbearable, you lose an agent, your editor leaves and you’re left orphaned. Your sales aren’t what you hoped and there’s question as to whether or not your next book will be picked up at all. Then there’s the dreaded: “Sorry, you’ll have to take a pen name because Jane Doe is dead.”

I’ve recently suffered a painful rejection from someone I didn’t expect. A reminder that no matter how many books you have in print, no matter where you think you are in your career, your books, your ideas, your style are subjective and you can be rejected as easily as someone who has never sold a book before. I don’t think “established” authors talk about this enough. How often we still suffer various forms of rejection. Each book is like an audition, and your work may or may not be selected for the competitive publishing schedule. (This is why it must be about the writing, but I digress.) In any event, one never really grows accustomed to rejection, not really, and when it happens, I think many of us find ourselves asking the same question:

Read MoreWhether you’re wondering what happens next in your story, want to write your first novel, or are about to start on the next instalment of your long-running series, there are always times when you’ll need inspiration. And it is often surprisingly close by.

‘Be observant,’ said the dramatist, Lajos Egri, ‘and you will be forced to admit that the world is an inexhaustible pastry shop and you are permitted to choose from the delicacies the tastiest bits for yourself.’

It’s that easy.

Except it’s not.

It’s difficult to suddenly ‘be observant.’ You don’t have time to sit around looking at things. You have to pick up the kids, get to the supermarket, make dinner, finish off that last game of solitaire. And you have to write!

Hemingway noted that it was difficult to be observant, but he also recognized its importance for writers. Being observant, he said in his 1935 Esquire article, Monologue to the Maestro, takes practice. ‘You should be able to go into a room and when you come out know everything that you saw there and not only that. If that room gave you any feeling you should know exactly what it was that gave you that feeling. Try that for practice.’

You don’t have to memorize every object in a room. There are simpler ways to get inspiration for your writing from observing the world around you. It can start with your morning shower.

Read More

Warning: Hacks for Hacks tips may have harmful side effects on your writing career, and should not be used by minors, adults, writers, poets, scribes, scriveners, journalists, or anybody.

You only get one shot to hook an editor or an agent. If you’re going to get them to like your novel, you’ve got to do it in the first 500 pages. It may sound harsh. It may seem unfair. But if you want to make it as a writer, you’ve got to deal with the fact that most publishing professionals will give you maybe 500 pages—or less!—to hook them. If they’re not invested in the characters, if they’re not completely immersed in the plot, if they’re not moved to tears by your imagery within your novel’s first six dozen chapters or so, it’s probably never going to happen. Don’t despair, though! In this month’s column, I’m going to cover all the elements you need to include to make your first 500 pages absolutely un-put-down-able.

Opening Action

The most important thing you can do at the start of your novel is to grab readers’ attention with an exciting opening! I’m not talking car chases—human conflict and emotion can sizzle just as much as a bank robbery if you play your cards right. A solid, action-filled opening should include the main character facing a problem, experiencing early setbacks, meeting friends along the way, getting rejected by their love interest, hitting rock bottom, then rising up to defeat their antagonist and win their beloved’s affection. It’s a lot to do, but if you use your elements of craft and write lean, muscular prose, you should be able to accomplish all of this by the bottom of page 500.

Stakes

Never take readers’ interest for granted. It doesn’t matter if you’ve got a colossal payoff on page 501 if you haven’t earned their attention by page 500. They need a reason to care—what’s at stake in your book? What’s your protagonist’s reward for success? What’s the penalty for failure? Stakes give readers a reason to care what’s happening, and it’s of paramount importance that you communicate those stakes within the first 125,000-odd words of your manuscript.

Read MoreEvery month, I examine some aspect of fiction—character development, plot, story structure, etc.—and offer advice and tips to help you work through the problems in your novel.

I have adapted many of the concepts you’ll see here from proven techniques used in modern psychotherapy. Hence: Fiction Therapy.

If you have a specific concern about your novel, send an email to jim [at] thefictiontherapist.com and I’ll do my best to help.

I recently reviewed a debut novel, The Valley at the Centre of the World. In it, the author, Malachy Tallack, describes life in a rural village on the island of Shetland. And he tries to do that in an accurate and honest way.

The problem is that not a whole lot happens in a remote village. The inhabitants go about their daily, seasonal and yearly rhythm. Strangers might arrive, but they’re usually looking for peace and quiet. Others might leave, but villagers are used to that too as people, mostly the younger generation, go off to pursue opportunities in the city. Even deaths in these aging communities happen regularly enough that there’s a certain routine to them too.

When nothing happens, nothing changes. And novels—stories in general—are all about change. There is (nearly) always a moment of self-realization for the (usually) main character.

And yet Tallack makes his story work.

How?

Read MoreI just had my in-laws staying. For seven weeks! Don’t get me wrong, they’re nice, easy-going people (at least, they kept telling me so), but I reckon Ghandi could test your patience after seven weeks in your spare room.

There was no one thing they did to annoy me (OK, there was one thing: “The car had an accident,” said Pops. It wasn’t him. It was the car.) It was all the little irks and ticks that built up over the time. And it was a long time. Seven weeks. Did I mention that already?

By the final week, I was frazzled. And my wife was away on business, leaving me to deal with them on my own. It came to a head one evening when I had to ask Mom, again, not to snap the spine of my paperbacks when reading them (“But it’s so much easier to hold in one hand.”)

I had to talk to someone. I had to get it all off my chest. But it was 11pm, who could I call? My wife’s days were full with meetings and preparing for meetings and, anyway, I’d just be moaning again if I called her. Who else then? Who could I call at that time of night to sound off?

It’s at these moments you realize the kind of support network you have. It’s a special kind of someone who’ll take that kind of call at that time of night and still give the level of sympathy you’re looking for.

There will be times in your story, too, when your protagonist needs support. And it’s not always obvious where that support will come from. Sometimes you have to dig deep to find that secondary character who will step in to save your hero just at the right time.

Read More