critique

As a connoisseur of writing how-tos (and yes, I had to look up how to spell connoisseur – and okay, “addict” might be a more accurate word), I have read a TON of them. And while I find valuable nuggets in nearly all of these books, lately I’ve noticed that many recent writing how-tos are essentially sharing slightly different flavors of some very similar core information.

So when I encounter a book about writing that offers some new (to me, at least) ways of looking at the craft, I sit up and take notice. My gushing ode to Chuck Palahniuk’s Consider This in this 2020 post is an example.

I just finished reading another such departure from mainstream writing how-tos: The Intuitive Author, by WU’s own Tiffany Yates Martin, who, in addition to being a wonderful writer and editor, is also an insanely good teacher and public speaker. Seriously, if you ever have the opportunity to attend one of Tiffany’s sessions or events, take it. And if you’re an author who speaks at literary conferences, trust me: you do NOT want to follow Tiffany. She’s that good.

Having seen Tiffany’s amazing presentation on backstory at WU’s brilliant 2022 OnCon, I knew what an extraordinary editorial mind she has, and how good she is at getting under the hood to amp up and improve your writing at multiple levels. So with The Intuitive Author, I guess I was expecting a book full of deep analysis into the mechanics of writing, along with some sophisticated editorial techniques. Instead, much of the analysis she offers in the book leans more towards the psychology and strategy involved in pursuing – and ideally, enjoying – the life of a writer.

I quickly realized I was not reading The Average Writing How-To, and I dove into the book with my curiosity piqued. (And yes, I had to double-check whether it was “piqued” or “peaked.” Got it right the first time – yay! Hey, it’s the small victories. But I digress…)

In short, The Intuitive Author is filled with insights and perspectives quite unlike those offered in the vast majority of writing how-tos currently on the market. And reading Tiffany’s book made me think about another writing how-to I’d recently read that takes a pretty big departure from most conventional writing wisdom: the provocatively titled Kill the Dog: The First Book on Screenwriting to Tell You the Truth, by author and screenwriter Paul Guyot.

What does this Guyot dude have against dogs, anyway?

Nothing, actually. Instead, the animal Guyot truly hates – and is taking a not-at-all thinly veiled swipe at – is the cat. Specifically, the cat in the well-known “Save the Cat!” series created by the late Blake Snyder.

If you’re not familiar, Snyder’s initial Save the Cat! book (STC to the cool kids) burst onto the scene in 2005 with a VERY structured set of templates for storytelling, which he reverse-engineered from studying many successful movie scripts. Targeted at aspiring screenwriters, Snyder’s methodology offered a compelling framework for them to adopt […]

Read MoreMy dad, Grant Overstake, has written millions of sentences. As a former journalist, pastor, and now novelist, he’s got what the writing world considers “chops.” Big papers like the Miami Herald published his sports column for years, and small papers had his by-line on every article from op-eds to sports to obits.

His young adult sports novels are precise, beautiful, engaging. His sermons, spoken word he wrote to help rural Kansans navigate their faith journeys and complicated lives in the late 90s, were captivating, heart-felt, well-rounded. This man has done it all in the writing world — if I listed his awards, I’d reach my word-limit in this article.

I decided early in my life that I, too, would be a writer. If you’re a parent and you try to get your kid to find passion in the things you love, you likely will feel one of two things: the sting of rejection accompanying an eye-roll, or the wave of pride accompanying an attempt. My first attempt was verbal storytelling, just like my dad behind the pulpit. It turned into written storytelling as soon as I could hold a pen. Sign me up, Dad! I wanted to be like him.

Sometimes, a sign-me-up attitude can be intimidating as a parent. What if your child is no good? What if they’re not coachable? What if criticism of them is too much? I don’t know what form of bravery swept me as a child, but I showed my award-winning journalist father my first attempt at a novel, written in a wide-ruled spiral-bound notebook.

“Don’t overwrite,” he said. “Simplify it. Here, read this.” And he handed me Hemingway, Herman Hesse, and Rick Reilly.

In high school, he read my articles for the school paper and with his bracing, left-handed scrawl, edited with no hesitation. I remember, at first, that it stung. I might’ve cried. I was fifteen, learning from a master. I worked harder, read more closely, listened carefully. I built my words on the true stories from a small-town high school where football reigned supreme. In this world, the girls on the sidelines weren’t writing articles; they were dressed in cheer uniforms, caught up in the spectacle rather than the storytelling.

I donned a cheer uniform, too, and learned and listened to how sports were played. I wrote for myself, for my classes, for my newspaper, for essay contests. I sought my dad’s praise, his admiration, his subtle nod that affirmed I’d done it right. I won some of my own awards.

I had to learn, from an amazing writer, how to accept what a first draft is: each sentence might change. Bones are there, meat needs to fill in around it. Simpler is better. Red ink is strengthening your work. None of this is personal – these words are not tattooed on you. Nothing is permanent until the paper’s put to bed, kid. I remember the smell of newsprint, the dusting of ink on the sides of his hands, his press badge on the kitchen counter, his fingers calloused with the grip of a pencil.

I learned how to accept his red ink […]

Read MoreCredit: ABC Studios

My fellow writers, we need to talk about the new documentary by Andrew McCarthy, BRATS. It’s not just a nostalgia trip. It’s about criticism and rejection and survival as artists.

The film is instructive because it’s not about how criticism landed on one person and their career. It’s a research study about how criticism affected a group of people, each reacting in their own way. This is what gives us options.

(It’s also about a writer with his own bruised ego. We’ll get to him later.)

Here’s the back story — a group of young actors were enjoying huge success when, as NPR puts it, “journalist David Blum wrote a story in 1985 for New York magazine titled ‘Hollywood’s Brat Pack,’ centered on time spent partying with Estevez, Lowe and Nelson, that cast shade on the group — lumping them together as unprofessional and over-privileged, while sticking them with a moniker which would follow them all around for decades.”

We follow McCarthy as he tracks down as many members of the so-called Brat Pack as possible to find out, thirty years later, how the nickname affected them, professionally and personally.

What might be astonishing for non-artists is how heavily being lumped into that group weighed on McCarthy, disastrous to his career and to him, personally. But this is not an unusual story for creatives. I see storylines like this—albeit not usually at this level of fame—and openness.

Let’s take a beat to be grateful for McCarthy here. One issue facing creatives is that so few people are willing to talk about failure, real or perceived, so our narratives are skewed and our models for how to deal with rejection and failure go missing.

As we move through the film, we watch McCarthy realize that his reaction was specific to him, and not a foregone conclusion.

There’s a slider scale, one might say, of reactions here. Rob Lowe and Demi Moore on one side, having forged on. Emilio Estevez and Allie Sheedy are somewhere in the middle, having struggled with the name in their own way.

But it would be a mistake to see McCarthy as sitting on the other extreme. We don’t hear from Molly Ringwald. Judd Nelson remains elusive. Anthony Michael Hall is never even mentioned by name. It’s possible that the hardest hit aren’t visible to us on the slider scale and that McCarthy sits dead center.

Meaning, McCarthy’s response, though he seems doomed in retrospect, was actually pretty damn healthy. He’s thoughtful, introspective—sober, alive—and seems to have a full, happy life. But he can’t help but look back.

And, for all of the buzz around mindset, this is such a fascinating deep dive.

Demi Moore emerges as a brilliant gift. It’s Moore who quickly breaks it down for McCarthy. The nickname had value because he gave it value. It became what he feared it was.

In an earlier segment, while talking to Sheedy, McCarthy talked about how, in his auditions, everything felt different. With Moore, he talks about his fear, before the article, that someone was always going to stab him in the back. With Estevez, he hints at his troubled relationship with his father, with whom he could never make things right, but, in the end, […]

Read MoreOctober was gracious with unexpected warmth and blooming dahlias. November funneled golden shafts of sunlight through dayglo foliage that refused to drop. December, the woodstove snapped with cedar, brightening the endless dark, while the open screen door off the kitchen let in cool air that feathered our bare feet. Winter played peek-a-boo and we fretted about the lack of snow in the mountains but were secretly glad we didn’t have to scrape ice from the windshields.

Then came January’s deep freeze. Now, I’ve lived in eastern Washington and in Colorado’s High Country and on the flat plains of central Illinois. Real cold is when your nose hairs freeze and you can’t catch a breath for the pain of icy air in your lungs. What we experienced — a few nights when the temps sank into the teens, well below our average winter lows of upper 30°s— isn’t going to impress anyone. But it did unexpected damage. Several of our plants and evergreen shrubs, including hearty ceanothus and myrtle, shriveled, their drooping, brown foliage falling hopelessly to earth. With the warm autumn and mild winter, these plants never properly hardened off; perennials and trees began the new year with fragile buds building on their stems and branches. We’d mulched in autumn, of course, and a few inches of insulating snow had fallen before the cold snapped, but without the opportunity to acclimate, the plants’ soft tissue was ruined by the sudden and sustained plunge in temperatures.

In my work teaching writing workshops and as a freelance editor, I often caution writers about sharing work too early. I’m now calling it the Soft Tissue Principle.

In our excitement about a story that compels us to the page and propels us forward, we rush pages into a critique session or press them into the hands of a friend, a partner or even another writer we trust, our desire to have our work validated clouding our judgment. We haven’t given our stories time to acclimate. A nascent narrative is full of tender soft tissue that needs to develop connective strength. The writer herself often needs the objectivity that comes with time: time to construct solid drafts and time to step away between each, coming at the story with fresh eyes and a 360° perspective.

Now, you might toss your premise out there to see how it lands. I met up with a former county sheriff, bought him a beer, and laid out the premise of a novel I was in the early days of sketching together, just to see if what I had in mind was even plausible. He decreed it to be so, and put me in touch with a former Seattle-area homicide detective who gave me even deeper insights and possibilities. I then ran the premise by my agent and with her thumbs up, I was off to the races. But it would be another three years of writing and revising before I felt the story was ready to share a draft with her, my first reader.

How do you know when it’s time to seek feedback? As in anything to do with writing, there are no hard and fast rules, only trials and errors and a certain rhythm you will come to understand […]

Read More

Ever taken a punch to the face? I have.*

Sometimes getting feedback on a manuscript feels very similar. I’m shocked, my head is spinning, I’m a bit bruised, and I want a nap. And maybe some dark chocolate, or a hug.

Taking criticism is hard, even when you ask for it.

I think the best writers ask for it. (Thanks to Ray Rhamey, we’ve all read what happens when the best writers stop asking for it.)

I’m lucky to have found critique partners I can trust to be honest with me. They’ve saved me from some serious mistakes and helped me sharpen my skills. Early in my career, I scrapped my (rushed) sophomore book that had been professionally edited and already had a cover, because multiple people I trusted said it wasn’t good enough. And they were 100% right. I didn’t even revise the book; I just wrote a new one from scratch.

An outside reader can see character issues that I can’t, the key elements I’ve failed to articulate because they’re clear in my head but not on the page, and the threads I dropped three chapters back because I was so focused on writing a kick-ass finale.

But my friends don’t leave me bleeding on the mat. They also tell me what they liked, what’s working in the story, and what made them laugh or cry (in a good way). They’ll happily help brainstorm solutions and read revised sections.

And I do the same for them.

It’s like having a good sparring partner. They reveal your weaknesses and force you to improve your technique to avoid getting hit again.

If you’re looking for your own critique partner, here are a few things to consider:

Read More

So often in the craft of writing authors are presented with black-and-white dos and don’ts, foolproof systems for creating best-selling stories, story-craft dogma accepted as gospel despite our industry being entirely built on absolutely subjective opinion: from beta reader feedback to what will appeal to agents and publishers to what sells in any given market to wildly varying critical and online reviews of the exact same book.

Despite that I have worked 30 years in this business offering exactly that—opinions and advice about what makes story effective—I do not like writing rules.

I’m a staunch proponent of the idea that every story is unique, as is every author creating it, and that effective stories grow from the inside out, not by having a rigid system or set strictures imposed on it from the outside in. I base all of my work as an editor—and the entire premise of my book Intuitive Editing (where I even put the word “rules” in quotes every time I use it)—on this idea.

But (always a but)…! It’s true that human beings tend to respond to story in largely predictable and conventional ways, our brains predisposed for certain storytelling conventions. It’s true that there are market realities, genre expectations, reader expectations. We can forge our own path in telling our stories, but the ultimate litmus test of whether they work is how well they engage and affect the reader. And this is something that we can learn by mastering and intentionally wielding elements of story craft that can elicit those results.

And yet invariably when I’m teaching a workshop, someone will bring up exceptions to every guideline for successful storytelling. I call this the “James Bond never changes” phenomenon, from a common comment I hear when speaking about character arcs.

And sure enough there are plenty of successful stories where characters don’t change. (I’m looking at you, Forrest Gump and John Wick.) Plenty of stories that don’t build to a clear climax (hello, Cloud Atlas), where characters don’t seem to have clear driving goals (’sup, Lebowski?), where so many of what we construe as the holy grails of storytelling simply don’t apply (I see your weird ass, The Lobster). And yet the story is still successful, whether critically or in its sales or in its audience devotion.

So while in my speaking, teaching, and writing about writing I usually cite stories that successfully illustrate effective use of the storytelling techniques I’m teaching about, after finishing a recent book I really enjoyed that conformed to very few of these “rules,” I thought it might be useful to analyze how it breaks them and succeeds anyway.

Why this story shouldn’t work

Jhumpa Lahiri’s The Namesake was recommended to me by a friend as her favorite novel (as much a subjective gray area of a concept as are storytelling “rules”).

Lahiri’s debut novel, published in 2003, followed her 1999 Pulitzer Prize–winning collection of short stories, Interpreter of Maladies. It received a very healthy number of high-profile good reviews, and also this painfully tepid one from Publishers Weekly. It has a 4.3 rating on Amazon with just over 10K reader reviews, more than 500 of which are 1- and 2-stars, and nearly 1,100 […]

Read More

Please welcome our newest contributor, Virginia Pye, to Writer Unboxed!

Virginia is the author of four books of fiction, essays, and short stories. Her latest historical novel, The Literary Undoing of Victoria Swann, was published in October 2023. Her collection, Shelf Life of Happiness won the 2019 Independent Publisher Gold Medal for Short Fiction and one of its stories was nominated for a Pushcart Prize. Her debut novel, River of Dust was an Indie Next Pick and a 2013 Finalist for the Virginia Literary Award. Her second novel, Dreams of the Red Phoenix was named a Best Book of 2015 by the Richmond Times Dispatch.

Virginia has taught writing at New York University and the University of Pennsylvania and, most recently, at Grub Street Writing Center’s Muse and Marketplace Conference in Boston.

You can connect with her here, on her website, or at the social media sites links listed below.

Welcome Virginia!

A question faced by all writers, no matter their level of experience, is how and when to solicit critical feedback. How can you know when your work-in-progress is ready to be seen and who should you trust to respond both honestly and constructively?

The decision is different for short stories. A critic reads them in full and can respond to a writer’s overall intentions. With a longer work, when a reader may respond to only part of the whole, comments can feel less useful. Novel workshops are often structured to offer feedback one chapter at a time. It works for some writers, but in my experience, piecemeal criticism, especially of an early draft, can miss the mark or even lead the writer astray.

The most useful feedback, in my view, responds to the manuscript as a whole. This requires greater commitment from a friend or colleague, of course. And from the novelist, it requires more patience with the process. We can’t rush to finish if we’re waiting to hear back from a reader who’s evaluating the book from beginning to end.

This slowing down can often work in the writer’s favor, a “forced” breather from a manuscript can create much needed distance, even before hearing any comments. More than once, a break from a novel-in-progress has helped me prepare for a critique that’s coming my way.

But when should we ask for this gift of time and insight from our first readers? It’s time to seek out first readers when you’ve done enough self-editing to not feel embarrassed by our effort, and yet still know the manuscript needs plenty of work. A first reader needs to see the big picture, assessing the novel in its entirety and not focusing on the sentence level.

The writer should guide their reader with basic questions, such as what works in my manuscript and what feels weak? What did you want more of? What did you find extraneous? An early reader should be someone whose literary tastes you trust. Not everyone is skilled at giving literary feedback, so you’ll want to avoid anyone who’s too prescriptive or insistent, as their opinions may undermine your confidence or constrain your imagination.

Even with the value and necessity of a first reader, I try not to share a manuscript until I’ve completed a full draft. For me, […]

Read More

I’m pretty comfortable with being naked. If I’m backpacking with friends and someone suggests a skinny dip after a long day of hiking, my clothes are off before she’s finished her sentence. I have plunged naked into Lake Superior, remote rivers in the Adirondack wilderness, and glacial lakes in Washington state (not to mention some neighbors’ pools).

Sharing my fiction, however, is a whole different kind of being naked, one that’s much more difficult. I’m currently more than 100 pages in to a new novel, my first in almost a decade. Thus far I have shown my WIP to exactly one person, the writing partner I meet with every month. With my previous novels (three published, two started and abandoned), I’d shown my writing to at least six or seven others by this point, including my agent and editor. But not this time.

I’m reluctant to share for several reasons. One, I’m in a honeymoon phase with this new novel. I love my story, I love my characters, I love the way it’s unfolding, and it’s a joy to work on. I’m not sure I’m ready to have someone point out the inevitable flaws and shortcomings of my beloved. Second, I’m writing at an unusually (for me) productive pace. I don’t want negative feedback to discourage me to the point that I slow down. Finally, I am naked in this book. The characters are not me, the story is not anything I have done or that has happened to me, but the insecurities, fears, lapses in judgment, failures, longings, griefs—I know those all too well. Sharing this book is showing pieces of my bare soul to the world.

Of course we all do that when we write. If a book is to have any emotional truth, then we have to write the hard, scary, unpleasant truths. It’s not easy for me to peel back the layers of myself and show those truths to others. Yet, getting feedback is a key part of the process of writing and refining and perfecting our work. How do you know what to show, when, and to who?

One of my friends doesn’t show anything to anyone until she’s finished a solid first draft. Another shares in thirds—give the first third to some select readers, then adjust, give the second third, etc. Some writers I know share with friends; others share with readers they’ve found through writing groups or on social media. So, almost 20 years and (almost) four books in to this whole process, here’s what I know:

Think about what you want. What’s your goal in sharing your work at whatever stage you choose to share it? Do you want encouragement that your WIP is good, some incentive to keep going? Or do you want to know what is or isn’t working, what plot holes you need to fix, what shadowy characters need to be more fully drawn? There’s value in most kinds of feedback. It’s important to be clear with yourself what you’re hoping to get from it.

Choose your readers carefully. If your best friend is brilliant and a natural editor and insightful but someone who hates Sci Fi and you write Sci Fi, she’s probably not your best early reader. Ditto your […]

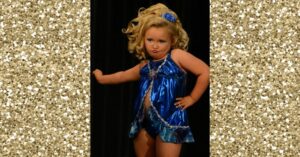

Read MoreFrom the Flickr of briantvogt, INFphoto.com.Ref: infusmi-20/21|sp

My last article, in March, addressed the process of finding and hiring a professional editor for a novel manuscript, comparing the insecurity this sparked as akin to entering one’s dolled-up toddler in a baby beauty contest. There might be harsh criticism and unflattering light. My metaphor was similar to one I’ve used to describe the sensation of having a novel launch into the world: It’s like pushing one’s naked toddler out into traffic to cross a busy intersection alone, while one can only watch what happens from the curb (and one is also naked). So, yeah. Anxiety is involved.

I promised an update in this installation, and I know that millions of you have been on the edge of your seats waiting to hear how it’s going.

It’s going well. Thanks for asking.

As I mentioned last time, there are many ways to find a professional editor. I’ve heard recommendations from writing bloggers, and there are many options available through reputable sources, such as Poets & Writers magazine and The Author’s Guild (if you’re a member). HERE are some great articles and advice from the WU archives.

I asked some fellow historical novelists about their experiences with editors-for-hire. Denny S. Bryce’s next novel, THE OTHER PRINCESS: A NOVEL OF QUEEN VICTORIA’S GODDAUGHTER, comes out in October from Harper Collins. Denny had this to say: “For my first novel, I hired a developmental editor. I wanted to work with someone who had been an editor at a traditional house and could help me with character arcs, turning points, and conflict. I considered the decision an investment in my writing career, and working with her one-on-one definitely contributed to my growth as a writer and the success of my first novel: WILD WOMEN AND THE BLUES.” (Kensington, 2021).

For me, a conversation with a fellow historical novelist led me to an introduction. Have you ever “met” a fellow writer on social media, and instantly liked their vibe, and then loved their book, and struck up some sort of friendship? That happened with me and Tori Whitaker, author of MILLICENT GLENN’S LAST WISH (Lake Union, 2020) and A MATTER OF HAPPINESS (Lake Union, 2022) when we bonded over launching books during a pandemic. Tori is a bourbon aficionado and perhaps something of an expert on the subject. I asked her to contribute a cocktail recipe to my annual series of December Instagram posts called “The Twelve Cocktails of Christmas”. (Tori’s Holiday Old Fashioned recipe was excellent, BTW).

Tori had this to say about her choice to hire an editor: “I retained a trusted developmental editor whose work I admired and who brought 20+ years’ experience teaching writing. That decision was indispensable in finally landing a deal for my debut novel—rather than having another book stuck in a drawer.”

Since Tori writes historical novels, I trusted her personal recommendation and contacted her editor, Jenna Blum. Jenna requested five pages of my manuscript and […]

Read More

Around this time last year, my mom said four words guaranteed to keep anyone up at night.

“I found a lump.”

If that weren’t anxiety producing enough, a diagnostic mammogram required a referral and she had no primary care physician. Those accepting new patients were booked solid for months because so many had delayed routine care during the initial COVID surges.

Two things were clear. First, she was going to have a wait on her hands to find out what, if anything, that lump signified. Second, I was going to make a bad situation worse if I gave in to the existential terror the word ‘cancer’ provokes. That demon had already claimed both my grandmothers and an aunt. A second aunt was securely in its clutches and passed away a few weeks ago.

The manuscript languishing on my laptop was the obvious place to pour all my nervous energy, but panic and focus aren’t exactly a winning combination, especially when I’m stuck. I needed a sense of direction. Accountability. Deadlines.

I needed something like Kathryn Craft’s “Your Novel Year” class.

I’d considered taking it before. I knew Kathryn, I loved her novels, and I suspected I’d work well with her. Barreling through a shitty first draft isn’t something I’ve ever managed to do, though. If forced to participate in NaNoWriMo, I would be clinically insane by Thanksgiving.

It took a nudge from our own Therese Walsh, combined with a major life upheaval, to get me to take the plunge.

If you have ever wondered whether this class or something like it would be worth the time and expense for you, here are some things to consider.

Know your mentor/coach

Handing over unfinished work, particularly in the early stages, involves some major creative risk. Trust is an essential component to a successful working relationship. If you can meet your proposed mentor, at a conference or at least online, you will be better able to gauge their critique style, how flexible they may be, whether you find them approachable or intimidating, etc. Do they have published novels? If so, read them. If they don’t wow you, hesitate before signing any contracts. If your prose is uber-descriptive and theirs is spare, know that you will be encouraged to rein yourself in. This isn’t a dealbreaker if you are secure in your own voice. If prone to blindly follow every suggestion, proceed with extreme caution. Do they write in the same genre (ideal) or at least have a lot of experience with it? If you write women’s fiction and they write spy thrillers, your proposed mentor may have the biggest name and the greatest connections and still be of no actual help to you.

Know that this is an investment with no guarantees

Intensive workshops, especially those involving developmental edits and individualized coaching, aren’t cheap. You will be making an investment, financially and emotionally. To get the most out of the experience, you must be willing to sacrifice a significant chunk of time and energy. In exchange, you will very likely have an improved manuscript, maybe even one that is publication worthy. Many good novels, even great novels, still do not sell. Are you prepared for that possibility?

Know your process

If you are the sort of writer who sets word count goals of […]

Read MoreWhile writing, are you worried about phrases like authenticity, loose ends?

If SO, ASK YOURSELF: WHERE SHOULD EACH OF MY CHARACTERS END UP?

Writing a novel is about communication. Outside of creating fascinating characters, a gripping plot, or filling pages with beautiful, engaging language, a novel should be clear in its purpose, its presentation and especially its ending.

In a recent review of Jennifer Haigh’s Mercy Street, author and critic Richard Russo not only wrote insightful comments about this excellent work of fiction, he also provided some creative insight for the rest of us.

Russo wrote: “At this point in a rave review, critics will sometimes introduce a quibble to prove that they’re tough-minded and serious and not easily gob-smacked.”

He then presents an authorial problem: do writers sometimes interfere with the lives of their characters, a kind of artifice at work? He writes: “But I’d argue the opposite: that it’s the characters themselves who have been working overtime their entire lives, to arrive where they land.”

His point becomes a fascinating way to praise a writer: stating that Haigh isn’t manipulating her characters, but rather paying close attention to their choices, bringing those choices to the page. When concluding his reading of the novel, and then his review, Russo writes that he was gob-smacked, because down to specific details, each of Haigh’s characters had changed during the novel, had revealed their true selves. Haigh had not left readers asking: why was that character even presented, what purpose did he or she have, or what was that character’s message?

FORMING A PLAN

After reading that final line of Russo’s review, I grabbed a pen, and in the margins of the piece, wrote down the names of all the characters in my WIP.

Had I given each of them the power to identify their needs, admit their mistakes? Had I clarified their positive actions and decisions? Was all of that on the page, or was I leaving too much to interpretation? By the end of the novel, had I made it clear where each of their lives stood?

Every character in your novel counts. Each has a voice contributing to the chorus of the story. At the end, where do you see each of them? How are they to live when the novel ends? It’s impossible to leave them hanging, because each character affects the overall story. Their part in the rise and fall of your story’s line and action has to have a satisfying ending.

In one of his workshops, Donald Maass addresses the issue of creating a character, but also never abandoning that character.

“Characters don’t arrive as blank slates. Indeed, in our back story worshiping literary era, there is hardly a character we meet who does not already carry a wound, a burden, or arrive in a state of paralysis. In some novels, recovery is not the end result, but instead the entire body and point of the story…more generally though, characters are people who are explained by their psychology.”

I agree, though I think within the creative process, characters often spring to life without regards to their psychology. It is something we begin to consider as they grow on the page, inhabit the list of character attributes Maass provided: values, dark fears, public face. And let me add: […]

Read More