Editing

Please welcome back Tiffany Yates Martin to Writer Unboxed today! Tiffany has spent nearly thirty years as an editor in the publishing industry, working with major publishers and bestselling authors as well as newer writers. She’s led workshops and seminars for conferences and writers’ groups across the country and is a frequent contributor to writers’ sites and publications. She is the author of Intuitive Editing: A Creative and Practical Guide to Revising Your Writing. Visit her at www.foxprinteditorial.com.

How to Weave in Backstory without Stalling Out Your Story

Your characters don’t just spring to life at the beginning of your story. If you’ve developed them fully, they are “real,” three-dimensional people with complex backstories and experiences that have shaped who they are at your story’s “point A” and directly inform the journey they take in your manuscript toward point B.

Yet how can you fluidly weave in all that depth and complexity without stalling pace and story momentum—getting bogged down in info dumps, flashbacks, or just too much exposition? As an author, how do you glance backward while still moving the story forward?

Let’s look at some practical techniques for developing and revealing who your characters were and are without slowing down the story of where they’re going, using three main ways of bringing in backstory: context, memory, and flashback.

Context

People don’t operate in a vacuum or on a single plane of existence. No matter how compelling our current challenges, conflicts, or goals may be, our experiences in any given moment are a sum total of all our previous experiences, memories, hopes, desires, worries that may be simultaneously present within us.

But dumping in swaths of a character’s backstory can stall momentum and yank readers out of the story. Instead, look for ways to weave this essential context in amid the forward motion of the scene.

Let’s say you have a scene where you’re showing your protag being fired. Unless her workplace has been a significant part of the story, readers may not know enough backstory to invest us, to let us know what’s at stake, to plant our feet in the impact of this event on her life and her arc. Depending on the purpose of this plot development, we might wonder:

What is she being fired for? Is it deserved or unjust? In either case, why is it happening? Did she know this was coming, or suspect it? What’s her boss like, and what’s her relationship with him? Her coworkers? How does she feel about this job? How long has she been with this company, and in this position? Is she good at what she does? What’s her immediate financial situation without a job? And her prospects for other employment?

This is just a sampling of the context that might be germane—key to letting readers know why this event is important, what it means to her and her arc. So how can you include this essential information without swaths of info dump that stop forward momentum cold?

Think of weaving threads into a tapestry, rather than basting in discrete swatches of a patchwork quilt. For instance:

Leah knew the moment she walked toward her corner office that something was amiss. Her door, always open literally and figuratively—always—was shut, and there was a […]

Read MoreIf you read writing books, you know that your characters should say whatever they say, with no help from you. “John said” or “Mary said.” Neither spluttered, murmured, extemporized, or expostulated. And no one ever said anything with an adverb attached – apologetically, artfully, dolefully, anything. In early to mid-20th century books, even successful authors just added “-ly” to any adjective, however unlikely — I’ve seen “boringly” and “heart-warmingly.” I think that habit is what killed the questionable art of adverbial speaker attribution.

It’s easy enough to know who is speaking when you only have two or three characters in a conversation. In fact, with two, you don’t have to do anything except let them talk – your readers can just follow the back and forth. But what do you do if you have a crowd to manage – a dinner party or the denouement of a complicated mystery?

The first step in keeping a chatty crowd under control is to know all the different ways you can flag the speaker of a line of dialogue. Speaker attributions, of course. “’We’ve got some old friends coming over tonight,’ Mary said.” But if you start ending every paragraph with a “said,” your readers are going to start tripping over them.

Injecting a little bit of action before a line of dialogue can flag a speaker. “Sky held out a hand with dirty fingernails. ‘Hey, dude, it’s been, like forever.’” You can also use a little interior monologue from your viewpoint character. “John could not for the life of him understand why Mary had invited Sky and Lotus Petal. They hadn’t seen them in years. But he may as well make the most of it. ‘It has. Good to see you again.’”

Read MoreThis month’s fiction therapy is a reply to a question from a member of the WU community, Nanette J. Purcigliotti.

I had edited some of Nanette’s work, and she had some questions afterwards, with concerns that I think many writers have about working with an editor. Here’s what she wrote:

“I thank you again for your revised suggestions. But they are your words, not mine. That doesn’t make me comfortable. How do I get around that?”

A fair question, I think, and I completely understand Nanette’s concern. Working with an editor means that some of that person’s suggestions, and even words, could make their way into your work, a work that is deeply personal to you. And this can be done to the point that it doesn’t feel like your words. I can get that, and I can understand that an author would be uncomfortable with that.

Here are a couple of sentences from Nanette’s text as an example of where she had this feeling. Please realize that these sentences are taken out of the context of the whole story, so they’re difficult to judge on their own:

Amanda’s mother appeared[1] in the bedroom’s oak-wood doorframe. She tapped the right heel of her Jimmy Choo shoes, said to her fourteen-year-old daughter[2], “This is no time to daydream. You’re beginning a new term in a new school.”

And here are two of the revision suggestions I made.

[1] The word “appeared” is a little passive. This seems to be a no-nonsense character. I think she’d wake Amanda from her dream with a hard rap on the doorframe, making Amanda turn to see her mother.

[2] The phrase “said to her fourteen-year-old daughter” here looks like exposition, like this is information the author wants to tell the readers. It would be better to let this detail come out in the story more naturally. And the next sentence has the perfect opportunity as you could revise that to: “You’re starting eighth grade at a new school.” Or: “You’re fourteen now. You won’t be able to dream your way through your new school.”

Here is Nanette’s latest draft of these sentences after my suggestions:

Read MoreWhen I first started reading books more complex than Green Eggs and Ham, I fell in love with series novels. I raced through the school library’s collection of The Hardy Boys and Nancy Drew. A friend loaned me the complete John Carter of Mars series – great fun when you’re twelve, though they don’t hold up very well – and another introduced me to the Chronicles of Narnia. I even went through my sisters’ old Bobbsey Twins books, which can be taken as a sign of how little reading material we had in the house.

What drew me to series was the comfort of going back to a familiar world, one that was already alive in my imagination. I looked forward to spending time with characters I’d already come to know and love. Besides, even if you’re a voracious reader, it’s a commitment to read an entire novel, especially if you can’t bring yourself to abandon a book you’ve already started. (I’ve mentioned before — it’s down in the comments — that I regret not being able to give up on Kurt Vonnegut’s Breakfast of Champions.) It was easier to commit to the next book in the series because I knew what I was getting into.

Now that I’m a grown-up editor, I can see why series also appeal to writers. It’s tough to write any novel without falling in love with your characters, and once these people are alive in your imagination, you want to keep following their stories. Besides, you can’t always really explore your characters in the space of one novel. There’s also the practical fact that agents and acquisitions editors like the way series novels offer upside protection. If your first novel hits big, your editor knows you have others in the pipeline.

But series books raise some questions that standalone novels don’t. For instance, how do you keep your characters consistent as they age? It’s part of J. K. Rowling’s genius that Harry and the Hogworts gang age plausibly throughout the series. As they mature, their relationships grow more complex, their internal struggles are more gripping, and readers are drawn deeper into the series.

But this kind of growth isn’t always possible, which is why some writers to simply freeze their characters in time.

Read MoreTwo months ago, in the article on expanding your world beyond the confines of your story, a commenter asked how much backstory she should include. I pointed out that your readers will assume that the history you’re giving them will play some role in the plot. The questioner had never thought about the link between backstory and readers’ expectations before. Now she is a little more aware of the web of connections between different parts of her writing.

I’ve written about this web in passing, while talking about genre, but it’s critical enough that it deserves a column of its own. Quite simply, you cannot write well if you’re not aware of how every aspect of your writing affects every other aspect of your writing.

This awareness doesn’t develop overnight. Most writers get into writing because they fall in love with one particular element of storytelling – getting to know an intriguing character, the joy of creating dialogue, the thrill of the slow ramp up to the denouement. When you start out, you aren’t yet aware of all the different moving parts that make up a novel – how you need to use beats to anchor characters in a physical location, say, or make sure each character’s dialogue has a distinctive vocabulary and cadence.

Even when you start to learn these things – reading books of writing advice or columns like this one – it’s easy to overlook the connections between the various bits of your writing. Those of us who write about writing tend to delve deep into one aspect of writing at a time. If you read enough advice like this, you couldn’t be blamed for thinking a novel is made up of discrete parts that you can just fasten together, tab A into slot B. If what you’re learning is something you’ve never thought of before, it’s easy to get so excited about it that it becomes the solution to all of your writing problems. When all you’ve got is microtension, everything looks like a scene that drags.

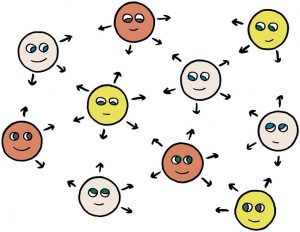

Read MoreA commercial airline pilot recently described how his job gave him a sense of how large the world really is. He would leave his home in London and drive to the airport among hundreds of other motorists and pedestrians going about their daily business. At the end of the day, he would land in New York or Johannesburg or Ankara and drive to the hotel among hundreds more. Eventually, watching these people pass by and imagining their lives made him aware that the people he’d seen that morning in London were still going about their daily business, just like the people at his destinations. This simple imaginative exercise left him with a sense that the entire planet was full of individuals living out their daily lives.

It’s natural to see the world only in terms of the people you encounter every day. We all know theoretically that there are seven and a half billion more of us out there, going to school in Lagos or heading to work in Asuncion or shopping for groceries in Osaka. We’re just not aware of them. We don’t feel they’re out there the way the pilot did.

It’s also natural to see your characters only in terms of the events of your story, giving them enough background to convey their personalities, making minor characters distinctive enough to be remembered. But you can give your story more depth – make your imaginative world bigger – if you learn to pay attention to the lives that your other characters, especially minor characters, live when they’re offstage.

When you create a minor character, think about who they are when your readers aren’t watching them. What do they do for a living? What are their good and bad habits? Married? Kids? What were they doing just before they entered the scene? What will they keep doing after they exit, stage right? If you can give your readers hints of life taking place beyond the confines of your story, you’ll make your fictional world feel not only larger, but less artificial and more authentic.

I’m currently working on a mystery in which the detective, in trying to get a sense of who the main suspect is, interviews the couple who lives next door to her. This couple only appears once in the book, for a handful of pages, but in that time readers see them arguing over who the suspect was. There’s no real anger or animosity in the argument. They still love and respect one another. They just have different ways of looking at the world and are comfortable expressing them. It’s clear this argument has, in various forms, been going on for years and will continue for years to come – it’s woven into their marriage. This glimpse of their life together stretching on past that one scene makes the couple feel more real, and the writer’s world feel larger.

Read MoreAfter seeing lots of hype in the media, I’ve been catching up with the HBO series Succession. The writers are there are expert at manipulating their audience. Their basic message is straightforward and not subtle.

The main characters – members of a family that owns a multinational media and entertainment empire – are horrible, selfish and self-absorbed. They treat everyone with contempt. But they reserve their true disdain for those outside the immediate family, in other words, those who are not super-rich.

Cousin Greg arrives bright-eyed and eager, desperate to ingratiate himself into the business. He meets Tom, who is also an outsider after marrying into the family. We’ve already seen Tom crave the attention of the patriarch, Logan, to the point of being sycophantic. And yet he still ends up the brunt of many insults as he struggles to fit in. Tom could be the perfect ally for Greg. And Tom appears helpful. On Greg’s first day, Tom tells him in a calm sympathetic tone, “If you need any help, seriously, any help, any advice … just, you know … don’t f***ing bother.”

Read MoreDan Brown has mastered the art of writing books that are hard to put down. This is remarkable because, in the course of most of his novels, he also introduces a wealth of background information. Just The da Vinci Code alone – to take his most popular example – educated readers on everything from Gnostic pseudo-Gospels to Renaissance cryptography. Yet his story keeps driving forward at a fast pace that never feels forced. One of the ways he does it is by creating effective scene endings.

Of course, your denouement needs to be clearly defined, wrapping up the plot questions you introduced near the beginning and giving readers a satisfying sense of closure. Your chapter endings need to be sharp, teasing future events to keep readers from closing the book at a convenient stopping point.

Scene endings are trickier to manage simply because there are so many of them. If you work too hard to bring a cliffhanger or sudden revelation to every scene, it won’t be long before your readers feel manipulated. You want endings that are subtle enough to feel organic, but still make readers want to keep binging your scenes like a Neflix series. So how does Brown do it?

Warning: there will be spoilers. I’ll be describing the content of key scenes so even those of you who haven’t read The da Vinci Code will be able to follow what’s going on. An additional warning: I’m well aware of Brown’s other literary shortcomings. He tells a ripping good tale, but as I read through it again for this article, I often itched to pick up my editing pencil.

So . . . the obvious candidate for a good scene ending is some new revelation that leads you to keep reading to find out what it means. And Brown does a fair amount of this – the second scene of chapter 86, where Remy, Leigh Teabing’s servant, reveals that he’s secretly working for the mysterious Teacher by turning a gun on Teabing. Or the end of chapter 98, where we discover that Teabing is, in fact, the Teacher and the earlier attack was staged.

But as I say, you can only include so many of these kinds of revelations. Brown often changes things up by ending a scene, not with new information, but with a revelation that rewrites what you think you already know.

Take, for instance, the opening scenes of chapter eight. Robert Langdon, an expert on symbolism, has just been brought in on the murder of Jacques Saunier, a curator at the Louvre, who wrote a series of cryptic and possibly satanic symbols next to his body while he was dying. Most of the first scene is spent on what the symbolism might mean, with the devout Captain Fache, the police inspector who summoned Langdon, acting hostile and suspicious toward the symbols’ satanic implications. Finally Langdon makes an obvious point that, if Saunier wanted to lead police to who killed him, he would have simply written down a name.

“As Langdon spoke those words, a smug smile crossed Fache’s lips for the first time that night. ‘Precisement,’ Fache said. ‘Precisement.’” And . . . scene.

Read MorePlease welcome developmental editor Tiffany Yates Martin to Writer Unboxed today! Tiffany reached out recently with an offer to write a piece for us on developing a stronger editorial sensibility, and we were immediately intrigued. She wrote:

Editing is something so many authors dread, but to me it’s where the magic happens. Like any other part of learning this craft it’s a skill that improves with practice–but it can be really hard to practice it objectively in our own work. I’ve found that authors don’t always realize how much value there is in editing others’ work and seeing it edited.

More about Tiffany from her bio:

Developmental editor Tiffany Yates Martin is privileged to help authors tell their stories as effectively, compellingly, and truthfully as possible. In more than 25 years in the publishing industry she’s worked both with major publishing houses and directly with authors (through her company FoxPrint Editorial), on titles by New York Times, USA Today, and Wall Street Journal bestsellers and award winners as well as newer authors. She presents editing and writing workshops for writers’ groups, organizations, and conferences and writes for numerous writers’ sites and publications.

Connect with Tiffany on her website, and on Facebook and Twitter.

How to Train Your Editor Brain

One of the hardest skills for a writer to master is editing her own writing. Assessing your work objectively when you are so deeply familiar with it can feel like trying to do your own brain surgery—but it’s a skill you can learn.

The best way I know of to switch on “editor brain” is to see others’ work edited. This is because you automatically come to others’ work with the mental and emotional distance it can be so hard to achieve with your own writing. With someone else’s story, you see—and evaluate—only what’s there, a crucial skill to develop in editing your own writing, spotting the things you’re often blind to in your own work.

Here are some of my best tips for how to do that:

Find a crit group—and home in on its hidden value

Participating in a critique group with other writers offers a regular opportunity to learn to analyze and assess effective writing (with a number of caveats, primarily that you find one that’s supportive and constructive, among lots of other baseline requirements; a bad crit group can do more damage to writers than almost anything else. Here’s a great article on red flags for unhelpful crit groups).

Yes, you’ll get the chance to receive feedback on your own work—revealing potential flaws you may never have considered—and gain direct experience critiquing others’ work. But the hidden value of a critique group is the opportunity to listen to critiques of others’ work. Observing multiple critiques of the same submission is an invaluable way to see not only what objectively works and doesn’t in a piece of writing, but to notice subjective differences as well—one reader’s Romeo and Juliet is another’s Fifty Shades of Grey.

Learning to edit your own writing is also about knowing when to stick with your vision even if it doesn’t work for every beta reader, and those variations of opinion are a […]

Read MoreLisbon, PT

In a recent interview for a writing blog, I was asked how publishing has changed since I’ve been an editor. The obvious answer is the rise of self-publishing and e-publishing. But these are only symptoms of something deeper.

Most publishing houses used to offer more support for midlist writers – writers who weren’t celebrities but who sold well enough to turn a decent profit. (They were “midlist” because they appeared in the middle of the list of new releases the publishing houses put out twice a year.) Then, starting in the 70s and 80s, publishing houses began to consolidate, and their approach to the business began to change. Major houses started paying large advances for established writers, looking for blockbuster-sized sales and profits. Spend a million dollars to buy the rights, spend another million promoting the book, and make five million in sales.

It’s not a bad business model, but it does limit one of the main avenues for talented new writers to break into print. Most writers will never become bestsellers, and certainly none of them start out that way. So how do the skilled, respectable writers who aren’t blockbusters get into print now that traditional publishers are a little further out of reach?

I’ve written before about small presses and self-publishing, both of which have their advantages and pitfalls. But one of the main dangers of either of these came home to me in this last month – they don’t have gatekeepers.

In order to get onto a publishing house list at all, you have to get past an acquisitions editor – the gatekeeper who both warned writers that their books weren’t ready for print and helped shape those who were close. As a result, even beginning writers had a trained professional watching over them to let them know if and when they had gone off the rails. There were still hacks, of course, but many writers who were only modestly popular in their day were skillful and engaging to read.

Of course, there are still strong, midlist writers like that today. But . . .

Read MoreDo you ever get the feeling that a scene you’re writing, just isn’t going to work? That no one would ever act this way? That no one would ever believe this outcome?

Do you ever leave the questionable scene in any way because you need this event to happen for plot reasons? Do you jump through mental hoops to convince yourself, well, maybe this is believable?

Maybe no one will notice.

Let’s consider a hypothetical scene:

A man goes into a forest. For plot reasons, the man needs to die in the scene. The writer takes an easy way out and makes a tree fall on our young man, crushing him to death.

I know I’m not giving you much detail, but I suspect you are finding this a bit far-fetched already. What are the chances that, of all the trees in a forest, the tree right in front of our poor guy would be the exact tree that falls, precisely when the man walks by? And that he wouldn’t hear it and get out of the way? It’s a bit convenient. And incredibly unlikely.

It isn’t as if our character walked onto a logging site where someone was actively cutting down trees. There wasn’t a hurricane, tornado, or earthquake tearing through this forest. It wasn’t even windy. The tree just fell on him. Boom. Our guy is dead.

We can try to convince ourselves the scene is logical. Maybe we go back into the manuscript and lay down some foreshadowing about another tree that fell. We could note in an earlier chapter that a tree in that same forest looked unstable. But none of these poorly disguised breadcrumbs can mask the fact that this scenario just wouldn’t happen.

You are probably thinking that this is a ridiculous example. Who would write such a scene? Who would think they could get away with something so obviously implausible.

Ummmm, it was me.

I wrote a scene in a draft of my book where a man runs into a forest and a tree falls on him. (I’m turning red with shame as I write this.)

Every time someone read the manuscript, I held my breath, waiting for them to tell me the scene was terrible. I did all sorts of mental gymnastics convincing myself that under certain circumstances this might happen. Right? I needed him to die and that conveniently falling tree got the job done.

No one said anything.

All the while, my stomach was twisting in knots because I knew it wasn’t working. But I refused to listen to my gut.

Read MoreLots of writing books, including Self-Editing for Fiction Writers, will tell you that you can use your paragraphing to emphasize key points. Want something to stand out? Put it in its own paragraph.

Picking which parts of your narrative you want to emphasize is trickier. As a rule of thumb, it’s a good idea to highlight the moments when your scene takes a sudden turn – when your viewpoint character suddenly realizes something, or another character does something surprising, or the mood of the scene simply changes. Just let less important moments develop within a single paragraph.

Today’s selection covers a variety of examples. Two of the mood changes – when Kellyn first feels threatened by the milk guy and when she begins to sympathize with him – are buried mid-paragraph. So is the moment of shock when she spots the sinister man staring at her. The moment when the milk guy first starts dumping milk does begin a new paragraph, but the writer could emphasize it even more by giving the sentence its own paragraph. Her decision to ignore the man in the suit is given its own, single-sentence paragraph, even though it’s a relatively minor development.

This confused emphasis makes it hard to track how Kellyn’s reactions build over the course of the scene. Take the metaphor of the eighteen-wheeler, for instance. It’s a good image, clear and powerful, but we don’t understand why she reacts to milk guy with such panic, then moments later is worrying about only finding change in her purse. If you would like to keep the metaphor, we need some interior monologue to explain her reaction.

Instead, I’ve simply cut it, and adjusted the paragraphing so that her feelings about the milk guy follow a clearer arc, and the panic she feels when she first spots the stranger continues to build.

Because it’s hard to judge the pace of a passage that’s been marked up as much as this one, I’ve decided to include a clean, as-edited copy as well, so you can get a feel for the finished product.

The man at the dairy case was clearly insane, Kellyn decided. [1] Scruffy, unshaven, tattered coat:, he looked homeless. but He didn’t quite smell the part, though, reeking more of paint than filth. The guy picked up a gallon of milk, and muttered something to himself, and put the carton back, either commenting on it or talking about the carton or to it. Interesting. ,

[Paragraph added] [2] bBut that didn’t matter. She Kellyn needed to get a jug of skim for the week. She sidled in and grabbed the nearest half gallon. The man snatched up another carton and . He peered at the label. “Ah,” he said, “ah.”

[Paragraph added] Then hHis fiery gaze fixed on her. “You.” [3]

Read More