Editing

A well-edited novel will stand out from the crowd and command attention—and even help boost sales. Professional editing will not only correct errors, it can clear away the clutter, tighten up the plot, invigorate characters, and strengthen the author’s voice.

In last months’ article, I concentrated on how to find a good editor to help you improve your novel and on what makes a good editor. But why bother with an editor in the first place? Do you really need an editor

This time, I outline five reasons why I—as an editor—think you should hire a professional to edit your novel.

Editing is like housework, it goes unnoticed unless it’s not done.

Professional editing is an indispensable—not just a desirable—part of a novel’s journey to publication. Editing can make all the difference to getting a novel noticed by a prospective publisher and audience alike. An editor will make sure the reader remembers the dazzling plot and characterisation, and not the problems with grammar. Authors need editors, just as editors need authors. It takes teamwork to craft a polished and captivating work that could become tomorrow’s bestseller.

Lots of authors ask friends to take a look at their novel. Most people are flattered by the request and are happy to help.

While any feedback is welcome and can help improve the manuscript, friends tend to give a lot of positive feedback and encouragement. They can gloss over some of the novel’s shortcomings to avoid causing offence. And there could be those who are just a little bit jealous and who will gladly recount a whole list of failings.

Professional editors, on the other hand, are experienced at giving criticism. They are systematic and thorough, covering not only familiar issues of grammar and punctuation but also matters of style, pacing, dialogue, plot twists, and fact checking (to name but a few). Above all, the feedback they give is honest and objective.

Like the author, editors want your readers to be focussed on the narrative and not be distracted by misspelt words or absent apostrophes.

Read MorePlease welcome new contributor Kasey LeBlanc to the Writer Unboxed team! From his bio:

Kasey LeBlanc (he/him) is a graduate of Harvard College and of GrubStreet’s Novel Incubator program, where he was an Alice Hoffman Fellow. He has been published by WBUR’s Cognoscenti and was a finalist in 2018 for the Boston Public Library’s Writer-in-Residence Position. He is currently revising his Novel Incubator manuscript, a young adult novel about a closeted trans teenage boy, Catholic school, and a magical dream circus.

We’re so glad to have you with us, Kasey!

—

If you’ve taken a writing class before, you’re probably familiar with the stereotypical “nightmare” student. He, for it’s often a he, is someone who thinks his words are a gift to humanity, someone who skewers other writers with his harsh criticisms, but is unwilling or unable to take feedback on his own writing. This person may be someone you’ve encountered in your own writing workshops, or perhaps is simply a fictional bogeyman meant to scare students into being better workshoppers. Either way, it seems that we focus a lot on this type of student.

I’ve taken a fair few workshops, most with the wonderful GrubStreet writing organization in Boston, and I’ve not seen many of this type of writer. But I have seen plenty of another type of writer. This writer is the opposite of the nightmare student in many ways. Instead of skewering their classmates’ work, they give advice generously and kindly. And rather than rejecting the suggestions given to them, they take them in. All of them. Or, when they don’t, they stress that they should somehow incorporate them all.

Today I would like to talk about this second type of writer and when you might choose to ignore a suggestion and stand up for your vision.

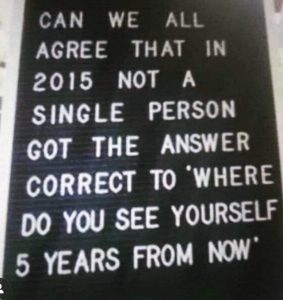

A book that pleases everybody is a book that pleases nobody. Or, as Aesop may have once said in a fable about a man, a boy, and a donkey (helpfully titled The Man, the Boy, and the Donkey), “If you try to please all, you please none.” It’s an unfortunate truth that in the end there can only be one version of the book we write. Along the way we’ll try out many different versions, but eventually need to pick just one. “Okay, sure Kasey,” you might be saying, “that’s a task much easier said than done.” As a writer known for drastically revamping and overhauling my book between drafts rather than getting to the nitty gritty line edit stage, I totally feel you. But if there is one thing I’ve become good at doing, it’s choosing when to listen to writing advice, and when to pass. And today I’m going to pass along three bits of advice I hope will help you.

1. Know your audience. Who are you writing this book for? My current manuscript is a YA novel about a closeted trans teenage boy and a magical dream circus. While I hope that my book can speak to many people, I write first for teens and for transgender people of all ages.

Read More

One of the more baffling problems I see with my clients is that they’re not keeping their writing real. Their stories might be full of tension and clever plot twists, their characters people I might like to know, but their writing is not rooted in life.

This problem most often shows up in descriptions. Their characters’ hair is “silky,” or wool socks “scratchy.” Hearts “pound,” muscles “ripple,” eyelids “flutter.” Sunsets “glow” or rain “pours.” They are simply writing the sorts of things that other writers have written, time and time again. It’s just as damaging when they go generic. Rooms are “large” or “opulent,” gardens are full of “flowers” surrounded by “trees,” lipstick is “red,” their characters eat “food.”

When you’re creating your fictional world, details matter. A clever story can be entertaining, but readers can’t lose themselves in your fictional world unless it feels real, concrete, definite. Clichés are tired and overly familiar. Generic descriptions are just filler, Pablum rather than steak.

Of course, most writers already know this. So why do they so often fall back on generic commonplaces and clichés?

They’re easy. They’re what comes to mind first. And they often look just good enough on the page that it’s possible to skip over them while you revise and never realize you have a problem. You have to deliberately focus to spot the places where you’ve taken the easy way out.

Other writers, I suspect, fall into commonplaces because they’re more interested in other parts of their stories. They want to get past the descriptions so they can dig into more dialogue, or they’re so caught up in the upcoming plot twist that their characters start talking banalities to get the dialogue out of the way more quickly. And all of that might be fine for a first draft. But when you’re revising, you need to rip out cliches like the weeds that they are.

Replacing them isn’t simply a matter of pulling out a Thesaurus and looking for alternatives to “silky.” You have to pay attention to the actual, real world. That’s where you go to find the distinctive, often surprising details that will make your fictional world real. For instance, the received wisdom is that teakettles whistle. But if you actually pay attention when one is coming up to a boil, you’ll find that it often bangs and pops (depending on how hard your water is) and then begins to hiss. If your readers have never noticed just how kettles boil, showing them that detail can make your fictional world feel more real than their everyday life.

To give you an example of the impact clear, reality-based details can have, Rex Stout once described Archie Goodwin visiting a witness’s apartment.

Read MoreI got a worrying email from an author last week. He had contacted me about a year ago for a free sample edit. He mailed me back after I’d returned the revised text to say he was happy with my work, appreciated my insight, but he had decided to go with another editor because they charged less.

His recent mail details a list of issues he then had with the other editor, including missed deadlines, errors introduced into his manuscript and basic errors missed. Most troubling of all, however, was that the cheaper editor had entirely changed the first two pages of one chapter. The author had originally written the narrative in retrospect—a common technique to fill the reader in on what has happened with these characters since we last saw them—but the editor had completely rewritten this as three pages of dialogue!

I literally gasped.

That, to put it mildly, is heavy handed editing.

I’m reluctant to revise dialogue in any novel because I feel the author knows the voice of the character much better than me. Of course, I’ll offer revision suggestions and correct any obvious errors, but there is, to me, something very intrusive about editing dialogue, so I’d certainly never consider rewriting whole pages in the voices of the author’s characters.

I’m still mentally gasping as I think about this.

This is not an isolated experience, I know, although it is perhaps the most extreme example I’ve heard in a long time. This, unfortunately, is a painful reality for many authors who put their money, faith and precious words into the hands of such editors, only to be disappointed when the text comes back with their voice and style usurped by the editor’s.

I understand that editing is a major investment in your writing career, but sometimes the cheaper option is not always the best or even the most economical. Such stories are bad news for authors and editors alike as, once confidence and trust in the editing process is shaken or lost, it can take a lot of hard work to restore an author’s faith.

A good relationship between an author and editor is essential to a successful publication. The difference between a compelling novel and a mediocre one is often decided at the editing stage.

So, how do you go about choosing a good editor for your cherished novel? How can you tell the difference between someone who says they’re good and someone who actually is good?

Read MoreLetting other people—even those close to you—read your novel for the first time can be stressful. You’ll wonder if they’re going to judge you, if they’ll recognize themselves in there, or if you really want your mother to know that you know about these things.

But after the first few times, you get used to it, and you’ll offer your manuscript to pretty much anyone who shows the slightest interest.

Then you come to the next level, maybe after a few rewrites based on the feedback from friends and family or even distant beta readers. After a while, you have to take that next step, to show it to someone in the publishing industry who will view it with a more critical eye.

An agent (and these days, it’s more likely to be an agent in the first place than a publisher) will pretty much give you a straight yes or no in the first instance. For most writers, even the ones who are now successful, the answer will often be no with little explanation beyond: it’s not for me.

An editor, on the other hand, will give you much more detailed feedback. It’s not unusual, for example, for me to write 20 to 30 pages of analysis for any one novel. And the nature of editing means that much of that feedback will come across as negative since you won’t improve so much of your novel by only hearing praise.

Read MoreDo you have an unfinished writing project that you had to set aside before it was finished? Maybe life events intervened. Maybe you got stuck and shifted to a different project. Maybe you just decided to wait for another year when daily existence didn’t suck the life and soul out of your creative energy. Do you think about whether or not to pick back up with that abandoned project and try to finish it? Restarting an unfinished project can be deceptively challenging, involving far more than simply writing the next scene. If the project has been dormant for a while, there’s a good chance that the story has grown ‘cold.’ You can’t remember where the plot was heading. The characters have lost their vivid presence in your mind and feel hollow. Or maybe you are a different writer now than you were before you had to take a break, and you worry that you just can’t match the tone.

Because of a variable schedule on my day job, my writing time comes in fits and starts and I’ve had to restart cold projects on a regular and repeated basis. Here is the process I go through to get myself back ‘into’ the story and some suggestions and strategies for how to revive a cold project and finish it.

First – a warning: When you set your expectations and your goals for the project, keep your flexibility level on overload. Your intention might be straightforward–get back to the project and finish it–but there are (at least) three likely outcomes when you try to restart a cold project:

All of these are good outcomes, because they all get you past one of the biggest hurdles to getting back into any writing project–finding the emotional strength to stop looking backward and to start looking forward.

What to Do Before the Writing Break (If you can see it coming).

Sometimes, you have some advance warning that you will have to take a break from writing. Maybe you are switching jobs, or have a huge deadline coming. Maybe you are making a lifestyle change that will curtail your writing time temporarily. If this is the case, in the last days (or hours) you have left to work on it, write down where you think the story is headed. This could be a synopsis, an outline, an abbreviated story, a few critical later scenes, or even just a few lines summing up the things you think should be important for the remainder of the story. Whether you write three lines or three thousand, do not sweat the word choice, style, or punctuation for this. This is not final prose, this is a story reminder, a memory jogger. Get down the basics, the who does what, and what happens […]

Read MoreOur houseraising, in 1992. I’m in the white shirt on the far right. Ruth is the photographer.

I’m writing this while they’re still counting votes after the election, when tensions are running high on both sides and the entire country could use a little something (non-liquid) to calm them down.

The best choice for readers is what might be called “gentle books,” straightforward tales of ordinary people in mostly every-day, low-key situations. No psychotics, no wrenching twists, no gore, no vampires or werewolves or demons.

Often comic, sometimes inspiring, these sorts of books were popular from the thirties right through WWII and into the sixties. Gentle books – the work of Angela Thirkell, D. E. Stevenson, Elizabeth Cadell, and many others – offered readers well-written, character-driven stories that reminded them of their own lives. Gentle books continued to thrive through the sixties and seventies with Miss Read, James Herriot, and others. Garrison Keillor and Alexander McCall Smith are among those who carry the tradition on today.

But don’t be fooled by the familiar settings and characters of these books. They are notoriously difficult to write well. It’s just too easy to sink into either banality or saccharine gooeyness – what might be called Hallmark Holiday Special fiction.

One problem is that the sources of tension available to you are, by definition, gentle. It’s easy to keep readers on the edge of their seats when your characters are trying to escape horrible deaths or fending off the destruction of the world. It’s a lot harder to keep readers interested over whether Bertie will be able to escape saxophone lessons or James Herriot will be the one who receives a cocoa tin full of goat droppings to analyze for parasites (considered an honor in Siegfried’s practice). Yet readers need to care enough about such minor, everyday problems that they will want to keep reading and will feel satisfied with the conclusion.

Read MorePhoto credit: Ruth Julian

Unless your writing is completely grounded in urban grit, sooner or later you’ll find yourself relying on nature. You may have a character who gardens or simply likes staring out the window at a garden – or a forest, hills, parks, sea, or desert. Your plot may need a tornado, flood, forest fire, hurricane, blizzard, or ice storm. You may want nature to reinforce the mood of your story or characters. Or maybe a character just needs to take a walk.

The key to any good description is to capture the idiosyncratic details – the handful of features that make a person or a place what it is, that capture its character. This is a lot easier to do with people and human-created spaces, since most of the details were put there by individuals, who can be pretty idiosyncratic. The details that make up a natural scene come from a lot of different directions, which makes it harder to pick out the ones that define the scene.

But it’s not only that nature has a lot of moving parts. The character of a natural scene changes from moment to moment. We’re in the throes of autumn here in New England, and the foliage has a completely different feel in bright sunlight – when the colors are all vibrant and on the surface, like the paint used in elementary school classrooms – and on overcast days – when the trees seem to glow from within.

So there is no substitute for the hard work of actual observation. Go to the places you want to describe and spend some time there, watching them change and develop. Learn to read the moods of the landscape, to understand it as deeply as you understand your characters. At the very least, you’ll avoid glaring mistakes like having daffodils and roses in bloom at the same time.

Read More

A while back, I texted my daughter.

Dinner is ready.

Her: Are you mad at me?

What? Why? I’m just saying that dinner is ready.

Her: Your period is really angry.

Perhaps you’ve encountered this yourself. These days, if your text message doesn’t end in an exclamation point, you come off as terse, and even (apparently) supremely pissed off. So, I guess dinner is ready! Hooray! Who knew we’d ever eat again?! *confetti emoji*

But there is something interesting about this phenomenon that applies to fiction writing–namely, while we toil over the perfect word choice to create the right mood and to elicit the intended emotions, those little flicks and curls are sitting there, waiting to do their own heavy lifting. They look small. But they can be mighty.

Here is a non-exclusive list of ways you can use punctuation to impact the emotion in your dialogue and narrative voice.

The Punchy Period:

Using full stops more frequently can add power and energy to your words. They can be used to emphasize an authoritarian voice because periods give the dialogue more control. For example:

“Today, you will be gathering stones from this field, beginning now and working until the sun goes down, and you hear my whistle.”

– versus –

“Today you will gather stones. You will start now. You will continue until the sun sets. Listen for my whistle.”

In which example does the prison guard command the most respect? In which example can you best hear the guard’s speaking voice? For most people, the answer to each of those questions is the dialogue with the most full stops.

But frequent full stops can also be used to indicate uncertainty, surprise, or the inability to understand; for example:

It was a ship. There. On the horizon. Yes. He was almost sure of it.

– and –

She stood. Right in front of him. Not at home with her mother. Not where she should be at all.

Frequent full stops can also show despair, like this example from Brooklyn by Colm Tóibín:

“Would you like me to call Miss Bartocci?” she asked.

“No.”

“Then what?”

“I don’t know what it is.”

“Are you sad?”

“Yes.”

“All the time?”

“Yes.”

Try using frequent end stops whenever you want to deliver an emotional punch.

But wait! There’s more.

Read MoreIf you believe mystery writers, an awful lot of murders take place in isolated country cottages or on ships at sea or on snowed-in trains. This kind of isolation makes it harder for the killer to escape, but it limits the cast, which makes the writer’s job easier. It limits the number of suspects, and readers know everyone from the beginning. Some more of them may turn up dead before the end, and one or two may turn out to be long-lost heirs or imposters. But the dramatis personae is stable from the beginning.

What do you do if your cast is less well behaved, though, given to popping in and out of the narrative in unpredictable ways? Maybe your plot structure leaves you no choice but to introduce a character early on and then sideline them or bring in a new character late in the game. Your readers naturally expect that your cast of characters is stable – that they know who the important players are as they read through the story. If you drop a memorable character halfway through, readers are going to subconsciously expect him or her to show up again before the end. If you introduce a new key character near the end, readers are going to feel cheated. Part of the joy of reading is anticipating what’s coming next, and readers get upset when you hand them something they couldn’t have seen coming.

I’m currently editing a story that, near the beginning, introduces a sharply-drawn character – the main character’s boss – who has an intriguing relationship with her. The boss later plays a key role in the main character’s life. The problem is, as the writer got deeper into the story, it grew to the point that it needed to be broken into three books, and the memorable boss we met at the beginning of book one doesn’t reappear until book two.

My client can’t just cut the character. She’s going to need him eventually, and readers need to know how the boss gets along with the main character before she undergoes some serious changes in that first book. The most straightforward solution would be to create some independent subplot involving the boss that my client could cut to from time to time as the story progresses, just to remind readers he’s still there.

Read MoreWriting is usually a fairly solitary experience, except maybe when your cats walk across the keyboard and add their contribution. But the publication process can be different, especially if you want to stand out among other authors and deliver a professional manuscript that can compete with the many thousands sent to publishers and agents every year, along with all the novels by indie authors and those already on the shelves.

For many writers, a major part of that professionalization is working with an editor. It’s also a major cost, and not only in cash terms but in time too. You typically send your manuscript to an editor when you’ve taken the narrative as far as you can on your own. The editor might take about a month to go through your text, and then send you back revision suggestions that require you to go through all 80,000 words or so all over again. And that’s where the real time cost can come in.

But, what many authors don’t realize is that it’s possible to spread that time – and the cost. Many editors offer the possibility to work on your book in sections, maybe 10,000 words at a time. That doesn’t necessarily only suit your expenses but also your writing routine.

For example, a staggered process really helps some of the authors I work with who have chronic illnesses and who can’t spend prolonged periods working on their text. Breaking their books down into blocks means they can revise at their own pace while still feeling like they’re making progress. They can then send the next section in their own time, often at moments when they’re in a less productive phase, but with the knowledge that I’m busy with their work, and they can pick up again when they’re ready once more.

Read MoreSix months into the worst pandemic in a century, we’ve passed five million cases with more than 170,000 dead, more than 30 million out of work, and the economy collapsing faster than it did during the great depression. Our politics have grown even more divisive, making it harder for us to act together. The world is changing around us in ways that we can’t possibly understand because we’re right in the middle of it.

So let’s talk about how this affects your current work in progress. That is, assuming you’re actually working on your novel instead of binge watching or binge baking or binge eating or binge drinking or crying quietly into your pillow every night. Or all of the above.

Of course, if you’re just starting out on a new manuscript, the virus offers all sorts of opportunities for drama. Covid is the ultimate A Stranger Comes to Town, upending peoples’ lives, putting them under strain, and revealing their true character – think Shane in virus form. But there’s something you’ve got to watch out for if you do decide to work Covid into your story — we still don’t know how the pandemic is going to end. Stuff could easily happen in coming months that will eclipse anything you might use as a background now, leaving your story feeling dated before it’s even finished.

Read MoreAt the beginning of 2020 (which must be about 40 or 50 months ago, right?), I stumbled onto a book that literally changed how I think about writing. During an email exchange with my dear friend and fellow writer Jocosa Wade, she recommended an early novel by Chuck Palahniuk, whom I only knew as the guy who had written Fight Club.

I loved the movie by the same name, but had never read any of his novels. To be honest, I’d always been a little afraid to read him, figuring he would be way too hip, dark and cynical for me. But Jocosa convinced me it was time to take the Palahniuk plunge.

Being a perennially cheap bastard, I hit the public library. Yes, this was back in that gilded age when I would still do things like a) leave the house, b) go to a public library – or any other public place, and c) actually touch books – or anything else that other people had likely touched. Ah, such sweet pre-Covid memories!

In searching the library’s catalog, I noticed Palahniuk had just released a new nonfiction book: a writing how-to called Consider This. The book had just come out that month, but to my amazement my local library system already had a few copies, so I nabbed one. My three-word review is below:

DAMN, it’s good.

Seriously, after just the first two chapters, I put the book down and got on the computer to order my own copy for my Kindle, so I could begin taking notes in it. Yeah, it’s that good. The thoughts and ideas Palahniuk shares are clearly stated and directly actionable, not pie-in-the-sky theoretical stuff. And he has such a unique way of looking at some of the most basic components and mechanics of storytelling, which he explains in ways that immediately make sense.

I’ve read a TON of writing how-to’s (it literally is my idea of a good time on a wild Friday night), and it’s been impossible not to notice that many of them are expressing VERY similar ideas. Not Chuck. He looks at writing in some ways that are completely new to me. And he’s a marvelous teacher.

For example, Chuck suggests that we incorporate these three elements in our storytelling: description, instruction, and either exclamation or onomatopoeia.

Instruction? Onomatopoeia? Wait, what? Here’s how Palahniuk clarifies this directive:

Most fiction consists of only description, but good storytelling can mix all three forms. For instance, “A man walks into a bar and orders a margarita. Simple enough. Mix three parts tequila and two parts triple sec with one part lime juice, pour it over ice, and—voilà—that’s a margarita.”

Using all three forms of communication creates a natural, conversational style. Description combined with occasional instruction and punctuated with sound effects or exclamations: It’s how people talk.

Throughout the book, Palahniuk repeatedly touches on tangible, nuts-and-bolts aspects of writing in ways I have never before seen discussed.

Read More