Diversity

Flickr Creative Commons: Bruce Guenter

An interesting thing has been happening to me with increased frequency: I’ve been asked to read friends’ and acquaintances’ manuscripts as a sensitivity reader for stories that deal with immigration. Because I am a Latina and an immigrant, and the authors who’ve requested I read their work are writing outside of their own experience, I’ve been asked to evaluate their work for authenticity. So far, I’ve had to turn down these kinds of requests because I’ve been busy with my own writing and mentoring work, not to mention personal commitments. But while I am not actively offering sensitivity reading as a service, there are several writers and editors who are. As sensitivity readers become more sought after in the publishing world, their role has been met with mixed reactions.

First Things First: What Is a Sensitivity Read?

A sensitivity read is an evaluation of a manuscript, usually one that touches upon characters and experiences of a marginalized group of people, that is performed by someone within that group to bring attention to potential inaccuracies, biases, and reinforcements of harmful stereotypes. Much like one might ask a cardiologist to read their story about a cardiologist for accuracy, a sensitivity read helps ensure that the portrayal of characters and worlds unknown to the author ring true. But more than that, it helps authors better yield the immense power and responsibility of their words. How many of us write because we want to make sense of the world around us? And more importantly, how many readers seek out our work in search of stories and truths that will, inadvertently or not, shape how they see the world?

This kind of work takes, well…work, at every stage of the process. There’s pre-writing research, there are revelations we experience during the writing itself. Post-writing, a sensitivity read provides yet another crucial layer of learning to the process. And yet, some authors continue to resist (and resent) the very idea of one.

Maybe it’s the name. The word “sensitive” has gotten a bad wrap lately, too often used to accuse someone of being too touchy or emotional. Perhaps the real question writers should be asking is: am I being sensitive enough? Am I using my senses to foster acute awareness and concern for the complexities of what I’m writing about? Isn’t that part of our job as writers?

Maybe it’s how it’s described. A recent story titled “Publishers are hiring ‘sensitivity readers’ to flag potentially offensive content” included an unfortunate word choice in the headline alone. The main purpose of a sensitivity read is not to avoid offending; it’s to avoid harming. If you’re writing about a person who is marginalized or underrepresented, understand the weight of what that means—for readers who rarely see their experiences reflected in books, seeing negative or erroneous stereotypes reinforced can be hurtful to them and their community. For readers outside of that experience, yours may be one of the few stories about a disabled or gay or black person that they read for years. Books carry authority; they have a way of seeming […]

Read MoreThe book market is shifting again as it has quite often in the last five years. Let’s face it. It’s desperately trying to keep up with our fast-paced world. How we discover books, how we purchase them, and how we read them have changed completely. All of that change is difficult for an industry that’s been around a couple hundred years, and it’s arguably even more difficult for those of us who create books in the first place. But the market is bound to evolve, especially in a digital, global world that must meet the needs of different kinds of readers. The market changes, sure, but is the craft of writing evolving too? I asked some established authors to see what they had to say. This is what I asked:

How has the craft of fiction changed in the last decade? Specifically, what have you noticed about books in terms of structure, characters, topics, trends, etc?

They said:

“I think in genre fiction, the readers are pushing for shorter chapters, quicker reads, and less depth. The publishers are following their lead. Literary fiction still allows the full beauty of the language to be explored, but genre authors have a unique challenge. Many of us try to inject a literary tone while still producing a page-turning quick read. That’s the sweet spot we are all shooting for, but with shorter attention spans, it is becoming a greater challenge.”—Julie Cantrell Perkins, NYT Bestselling author of The Feathered Bone

“I think the lines between genre and literary fiction are blurring. I think genre lit is becoming more character driven and nuanced. Literary fiction is becoming a little less self indulgent… stuff needs to actually happen in the book. In all cases I think the reader is beginning to expect more in terms of balance between engaging story and well-crafted prose.” —Aimie Runyan, author of The Daughters of France series

“Many published novels are shorter than earlier works, often less than 100,000 words and/or 300 pages and also much more first-person and multiple viewpoints rather than third-person following one pov.”—Sally Koslow, author of The Widow Waltz

“In women’s fiction, we’ve gone from which designer shoes to wear to much darker, beefier themes. I see this as women claiming literary equality: there’s no problem a male character can tackle in a novel that a female can’t–and the female may learn more from it.”—Kathryn Craft, author of The Far End of Happy

“I think there are expectations to crank out books faster and faster. Especially for romance and contemporary books (thrillers, woman’s fiction, mystery, etc).”—Amy E Reichert, author of Luck, Love, & Lemon Pie

Other changes authors have noticed include:

Read MoreImage – iStockphoto: Inner Vision

‘Get the Message Across More Forcefully’

Last week’s AWP conference—the Association of Writers and Writing Programs (February 8-11)—was the usual sea of campus-based students and faculty members, university presses, plus assorted services for publishers and authors.

Early estimates were of some 12,000 people being in attendance. The book fair area of booths and tables was said to have more than 850 outfits represented. And in roughly 550 sessions, attendees heard and debated issues, many of them based in questions of diversity. I wrote an advance piece at Publishing Perspectives on the program’s stated mission of inclusiveness.

Being set as it was in Washington, D.C., however, the political nature of so many of its admirable points of support for writerly egalitarianism was heightened. Some of the attendees participated in demonstrations of their political leanings. I’d guess that very few sessions went by without some mention, pro or con, of the White House administration a few blocks away.

From the hotel, I could see the top of the Washington Monument and the Capitol—they seemed farther apart than in the past.

I was on a panel called Current Trends in Literary Publishing, a session that’s put together and moderated annually at AWP by Jeffrey Lependorf of CLMP, the Community of Magazines and Presses dedicated to literary work and to literary journals in particular. With us were Katie Freeman of Penguin Random House’s Riverhead Books; Dawn Davis of HarperCollins’ Amistad; Literary Hub’s Jonny Diamond; and Michael Reynolds of the independent publisher Europa Editions.

It was Reynolds who, in reminding us that Europa Editions was originally founded in Italy, told the audience that current events are causing houses like his to reflect on why they choose to publish literary fiction. His house has a Turkish author, for example, who’s currently jailed by the regime there, as are many in publishing and journalism. And as the pressures of nationalism increase in many parts of the world, including the States, the Philippines, the United Kingdom, France, what is it about serious fiction that seems to resonate so strongly for so many?

“What about current events,” Reynolds asked, “makes it important to publish literary fiction?

“Do we need to provide more context?” he asked. “Do we need to frame our publishing program differently in order to get the message across more forcefully in this moment?

“In publishing literary fiction,” Reynolds said, “I think we all know that reading fiction—reading fiction in general—is good for our empathy. And I think a publishing program can think about social empathy, and global empathy.”

Several of us on the panel would go on to seize on that phrase Reynolds had given us, “global empathy.” My own key message to the event was very close to his but with that usual provocateur angle: I urged the room of several hundred people to take their belief in literary fiction—and especially in its peculiar capacity and internationalism to promote “global empathy”—and begin to speak more loudly, more proudly about it. I see this political era as a stark opportunity to demonstrate literary’s importance.

And that brings me to my provocation for you today.

Read MoreCan writers in the dominant culture be confident that they are speaking authentically, meaningfully, and vitally about this real America? In September at Bouchercon, Sisters in Crime held a workshop addressing the challenge of diversity. Panelists Frankie Y. Bailey, Cindy Brown, Greg Herren, and Linda Rodriguez join us at Writer Unboxed today to share some of the highlights and major takeaways, including, LGBTQ characters, disability in plotting, diverse settings and the extraordinary challenge of dialogue.

Frankie Y. Bailey is a criminal justice professor at the University at Albany (SUNY). A native Virginian, she writes a series featuring Southern crime historian Lizzie Stuart. Having spent much of her life in upstate New York, she also writes near-future police procedural novels featuring police detective Hannah McCabe–most recently What the Fly Saw. Her non-fiction focuses on crime history, and crime and mass media/popular culture. Frankie is a past president of SinC and a past EVP of MWA. Connect with Frankie on Twitter and Facebook and on her blog.

A former theater professional, Cindy Brown was the first director of ARTability, a national-award-winning organization that provides access to the arts for people with disabilities. She’s worked as an ADA consultant, written about accessibility for the Smithsonian Institution and the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, and received the Mayor’s Award from the City of Phoenix Mayor’s Commission on Disability Issues in 2004. Cindy became a full-time writer in 2007 and is now the author of the Agatha-Award-nominated Ivy Meadows series, most recently Oliver Twisted, a madcap mysteries set in the off, off, OFF Broadway world of theater. Connect with Cindy on Twitter and Facebook.

Greg Herren is an award winning author and editor from New Orleans. He has written over thirty novels under his own name and various pseudonyms, edited twenty anthologies, and has published over fifty short stories. His most recent novel, Garden District Gothic, is the seventh Scotty Bradley mystery, He also edited this year’s Bouchercon anthology, Blood on the Bayou. Greg says, “As an out gay man who has been writing about gay and lesbian characters for over fifteen years, I would love to see more LGBT characters in mainstream works by mainstream writers.” Connect with Greg on Twitter, Facebook, and on his blog.

Linda Rodriguez’s book, Plotting the Character-Driven Novel, forthcoming this month, is based on her popular workshop. Her fourth mystery featuring Cherokee campus police chief, Skeet Bannion, Every Family Doubt, will be published in June 2017. Her three earlier Skeet novels—Every Hidden Fear, Every Broken Trust, and Every Last Secret—and her books of poetry—Skin Hunger and Heart’s Migration—have received critical recognition and awards, such as Malice Domestic Best First Novel, International Latino Book Award, Latina Book Club Best Book of 2014, Midwest Voices & Visions, Elvira Cordero Cisneros Award, Thorpe Menn Award, and Ragdale and Macondo fellowships. Her short […]

Read MoreA few months ago, I read a fascinating article on the Stuff You Missed in History Class blog. After receiving innumerable complaints about their podcast which boiled down to either “you talk about women too much” or “you only talk about women”, Tracy Wilson went back over the episodes they’d produced and put together graphs showing the breakdown between episodes focused on men, women, and ungendered events. You can see the results here. But, unsurprisingly, (spoiler alert!) they showed that stories about women made up roughly 30% of their content.

Those results tie directly into the recent research that shows that men talk significantly more than women in a mixed group, but women are perceived as being more talkative and taking up more time. There are various explanations for this disparity between objective reality and perception, from old-fashioned sexism to differences in male and female speaking styles. Whatever the reason, however, it’s safe to say that the old “truism” about women talking three times as much as men is exactly the opposite of truth.

I was reminded of both these things a few days ago when my nine-year-old son asked, “Why do we only ever read books with girl main characters?”

Now, as a mother of two boys, I take particular care to make sure that the books I read to them feature a mix of male and female protagonists. For every Charlie and the Chocolate Factory there’s a Matilda. For every Harry Potter there’s a Wrinkle in Time. So my first reaction was to feel pleased that my attempt to provide gender-equality in our shared stories was working.

We’ve just finished reading Catherynne M. Valente’s glorious novel The Girl Who Circumnavigated Fairyland in a Ship of her own Making, starring September — a twelve-year-old girl from Omaha who travels to Fairyland– and have moved directly on to Barbara O’Connor’s How to Steal a Dog, starring Georgina — a young girl living in a car with her mother and little brother when they suddenly find themselves homeless. I don’t remember what we read before that, but after my moment of pride, I fell into doubt. Have I pushed the pendulum too far and deprived my son of his heroic male role-models.

So I took my son by the hand and went to find out whether his assertion that we mostly (because “always” was clearly an exaggeration) read about female protagonists was true.

Read MoreImage – iStockphoto: AH 86

A Minority-Run Industry

Nielsen staged its inaugural Romance Book Summit yesterday (July 14) at the Romance Writers of America’s (RWA) conference in San Diego. We knew we’d see plenty of good statistical research and a lot of thoughtful, intelligent speakers.

Kristen McLean

The program’s lead, Nielsen’s director of new business development Kristen McLean, over the years has become an increasingly compelling industry analyst, focusing first mostly on YA and children’s literature and now looking with hard compassion at romance.

And we saw was a formidable show of willing self-examination, a group of publishers and authors working together constructively.

The tone was set by the author Caridad Piñeiro’s keynote, which she called “Setting the Table: Why There’s Room for Everyone in the Ever-Evolving Romance Business.”

Based on an anecdote around the first Christmas meal for her Cuban-Italian marriage and family members, Piñeiro echoed what she’d said to Jane Friedman and me in a May interview for The Hot Sheet:

“I am proud to be a member of one of the largest minority-run industries in the country. At every level, from publisher to editor to agent, author, and reader, women dominate the romance book business. Because of that, romance novels provide a wealth of opportunities for women at all levels and speak to women in very unique ways.”

And while she’s right on these points, Piñeiro was winding up into a look at how romance needs to “find a place at the table” for all its people. Since she spoke of women, here’s one instance of interest: sixteen percent of the romance readership, Nielsen’s research shows, is male. And most of that group identifies as heterosexual, not gay. How many of the writers of romance are male?—Nielsen’s figure is 3 percent.

Another intriguing data point McLean would bring out: Nielsen’s research shows that 55 percent of all romance readers asked said that it was more important that imprints and/or series reflect diverse backgrounds than that they reflect the readers’ specific ethnic backgrounds, and this finding seemed strongest in the younger spectrum, those aged 13 to 29. On the other hand, 41 percent of minority readers of romance said they preferred buying their books from imprints and/or series reflecting a diverse background, compared to 23 percent of white readers who said this.

As Piñeiro pointed out, romance is “ever-evolving” because sub-genres wax and wane in popularity. One example: a renewed uptake these days for western romance, as many writers at RWA can tell you, is cowboys. And what began to emerge as the day went on, was an understanding that the diversity of sub-genres in romance itself may point to its capability to lead the way in publishing’s industry-wide crisis of needed diversity.

My provocation for you today has two elements to it.

First, I suggest that romance may be the genre best ready to lead with deep, society-reflecting diversity ahead of other genres, for the very reason that its writers and readers are accustomed to exploring and accommodating variety. When Radclyffe, the influential lesbian author and publisher, told us that five years ago she could still get a note from a […]

Read MorePhoto by George A. Spiva Center for the Arts

There is no such thing as the “average reader.”

I usually see references to this mythic creature — the average reader — in one of two contexts.

First:

“I’m going for mass market appeal — I think the average reader would enjoy my book.”

Second:

“Well, the average reader obviously doesn’t know what good writing is. Why else would they buy crap like (popular bestseller)?”

I’m going to tackle these two usages separately.

The myth of the “mass market” average reader.

Readership is not monolithic. In this day and age, there really isn’t a mass market consumer, and very few mass market products. Commodities like flour and milk are split into more and more specific categories: whole wheat, unbleached, gluten-free, 2%, 1%, lactose-free, organic, goat, cow, almond, soy, etc.

So how could something as subjective as reading taste be considered “mass market”?

Yes, you’ll have some FOMO (Fear Of Missing Out) readers, who are jumping on the bandwagon, only because they want to discuss what everyone seems to be reading. But with the plethora of entertainment choices out there, reading isn’t necessarily the water-cooler discussion point it used to be. (Come to that, there aren’t really water-coolers that people chat around. Break room discussion? Facebook discussion?)

This isn’t something to bemoan. This is not a cultural commentary, and quite frankly, I am not going to waste time making a judgment on a nostalgic “mass market/higher reading” audience. This is the reality we are working with. Story comes in a lot of forms. There are simply more options than there ever have been before, and we have got to stop being so precious about it if we hope to create a sustainable living from it.

The days of demographics.

Demographics are the segmentation of a group of people by factors like age, ethnicity, race, religion, income, and education.

In the earlier days of marketing, any consumer description was couched in demographics. For such-and-such a product, they might describe the ideal consumer as:

Woman, 30-40’s, married, household income of $60k, lives in suburbs.

The assumption is that people of the same gender, marital status, income, etc. would have the same tastes, the same interests. More importantly, they could be reached by the same marketing techniques (which, at the time, were “push” promotion, spread through heavily controlled, one-way mass media.)

The rise of psychographics.

As people started connecting in new ways with increased and easier communication options, and sales of products became easier and more global, it became clear that simple demographics weren’t as effective as they used to be.

For example, the original assumptions of the rise of the romance genre was that it was mainly read by suburban housewives of lower education and household income, so marketing should appeal to that supposed “demographic” by referencing things like “when you need a break from the kids!” or literally marketing them like bleach or other household products, emphasizing similarity and brand over individual authors.

While this worked incredibly well for a while, the “category romance” has been in documented decline for the past decade, as their audience is, essentially, dying out. It’s simply easier to get exactly what you want now, rather than settling for a limited range of “commodified” genre offerings. The success of re-tooled category romance has come from the increased sharpening of focus by category lines and the diversification of […]

Read MorePlease join us in welcoming guest Maha Gargash to Writer Unboxed. An Emirati born in Dubai to a prominent business family, Maha studied abroad in Washington, D.C., and London. With a degree in Radio/Television, she joined Dubai Television to pursue her interest in documentaries. Through directing television programs, which dealt mainly with traditional Arab societies, she became involved in research and scriptwriting. Her first novel, The Sand Fish, was an international best seller. Her second novel, That Other Me, is out on January 26 via Harper Collins.

“I’m writing for a Western audience.” It’s a thought that sits quietly in the back of my mind as I write. Sometimes I’m aware of it; other times, I’m not. Always, I find myself adjusting the narrative—whether it’s to do with structure or flow—in order for the story to be absorbed more readily by a Western reader. Recently, I’ve been wondering why this was so and felt the need to examine the matter more closely—culminating in this article.

Connect with Maha on Facebook and through comments to this post—but please note she will be responding from her home in Dubai and because of the 15-hour time difference from the U.S. there may be a delay in her replies.

Writing for a Western Audience

It’s easy to understand why Western readers might be interested in a novel coming out of the Arab world. No longer is the region as remote as it once was. With the ease of travel and increased integration through the interchange of views, products, and ideas, Western readers seem keen to take a peak through a window that remains largely opaque.

And here comes the challenge. Yes, there are many novels from the Arab World that tackle all the familiar themes, whether these be the Palestinian struggle for a homeland or the effects on children growing up in war torn countries. But not all are written with the Western reader in mind.

It’s not only that the Arabic language is complex and poetic, a reservoir of beautiful words. To the Western mind, Arabic thought also renders a complexity and contrariness hard to digest. To add to that, not all Arabs think the same, or express themselves the same way, or even dress the same way. This is hardly surprising for it is a vast region expanding from the Atlantic ocean in the west to the Gulf waters in the east.

Although I always keep in mind the readers of my stories, rarely do I think of them as being wholly Western or Eastern in thinking. Instead, I concentrate on producing a story well told that presents a different reality. Ultimately, it’s the conflict within the story and the interaction of the characters that keep the pages turning.

Still, there are bound to be concepts that might alienate a Western reader. The test is in telling the story without allowing it to get bogged down by over explaining things: customs, traditions, and a people’s outlook.

Read MoreToday we’re thrilled to have Kristina McMorris join us. Kristina is a New York Times and USA Today bestselling author and the recipient of more than twenty national literary awards, as well as a nomination for the IMPAC Dublin Literary Award, RWA’s RITA® Award, and a Goodreads Choice Award for Best Historical Fiction. Inspired by true personal and historical accounts, her works of fiction have been published by Kensington Books, Penguin Random House, and HarperCollins.

The Edge of Lost is Kristina’s fourth novel, following the widely praised Letters from Home, Bridge of Scarlet Leaves, and The Pieces We Keep, in addition to her novellas in the anthologies A Winter Wonderland and Grand Central. Prior to her writing career, she hosted weekly TV shows since age nine, including an Emmy® Award-winning program, and has been named one of Portland’s “40 Under 40” by The Business Journal.

So often, novelists are warned not to incorporate stereotypes into our characters, and yet stereotypes exist for a reason: because they’re usually based in truth. There are so many literary rules—not to mention PC guidelines—we’re afraid of breaking. I hope my post will help liberate some writers who might feel hindered in this respect.

Connect with Kristina on Facebook and Twitter.

Stereotypical Perspectives

The theme was “Asian Invasion.”

For years I had been tasked with planning an annual appreciation party thrown by my family’s company. Invitations would reveal the surprise theme each year, spurring the vast majority of our five hundred guests—from vendors and customers to politicians and journalists—to find or create suitable costumes to compete for the highly coveted first-place title. Up until then, we’d covered the Roaring 1920s, mobster-era ’40s, ’50s diner days, and disco glam of the ’70s. Sprinkled between those had been a Wild West saloon, sports pub, Vegas casino, and a French Renaissance-style masquerade ball. In various ways, culture played such a key role in those events that ultimately it didn’t feel a far stretch to move on to an Asian theme.

“Throw PC out the window! Just have fun!” we told our guests at a time when the fear of offending others had seemed at an all-time high (a miniscule level compared to now). It didn’t require explanation that the reason my family could host a party encouraging creative Asian costumes was simply this: We’re Asians. (Or half, in my case.) I suppose you could say we had an ethnic “hall pass.” And that allowed us, for a single evening, to extend that pass to others.

On event day, it was a delight to watch people pour out of their cars dressed as Chinese take-out boxes, sumo wrestlers, sushi rolls, and the stars of The King and I.My sister and I went as the Siamese twins from the film Big Fish, our dresses connected at the hip by Velcro. We laughed at ourselves, and others, entertained by the silliness of it all, despite—or perhaps due to the fact—that bits of truth had inspired those costumes.

With a father from Kyoto, I was raised in a house where shoes were removed […]

Read MorePicture yourself in a strange coffee haven, sans plasticine porters with looking glass ties. It’s San Diego in the mid-1990’s and, although smoking indoors has been banned for a little over a year, the lingering haze of ten thousand clove cigarettes gives everything the feel of a White Diamonds commercial. I’m at the counter ordering a round for my buddies when our high-maintenance friend arrives, out of breath and late, again.

“What do you want?” I mouth the words across the room so as not to disturb a reading of The Vagina Monologues.

“A caramel macchiato, 2% organic, extra-shot, extra-hot, extra-whip, with three Splendas and a dusting of dark chocolate,” he mouths back.

I shoot him an “okay” sign with my finger and thumb, turn to the Liz Taylor impersonator and say, “Make that five regular coffees.”

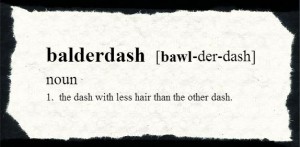

We’re there for our weekly game of Balderdash, a competition of intellect, creativity, and bullshittery –- the perfect distraction for the writerly sect. If you’ve never heard of it, in a nutshell, players pick a word, write their “definitions,” read them along with the correct answer, then vote on which is real. Points are awarded to those who choose the correct definition and to those whose definitions are chosen.

I open with this vignette because among that group was my best friend, Jeff, whom I could never fool. While the others fell prey to my pseudo-Websterisms time and again, every attempt at tricking him was not only dashed, it was balderdashed.

“How do you always know?” I asked one night after a particularly grueling tournament ended with the announcement they had run out of everything but decaf.

“Yours sound like you.”

“Huh? Whaddya mean they sound like me?” I mean, seriously. Pick a word –- any word -– balderdash, for example. Does this not sound like it was ripped straight from the pages of the OED?

Balderdash: (n) the dash with less hair than the other dash.

I rest my case.

Then again, maybe I rest Jeff’s case. “It’s the way you put things,” he continued, “the phrasing, the word choices, the style –- the everything. Sure, they may sound like dictionary entries, but dictionary entries you wrote — even when they’re the correct definitions — if that makes any sense.”

Personally, I think it’s because I typed them.

And that, my friends, was the day I discovered my words had a voice behind them, and that voice was distinguishably mine.

The Authorial Voice

We’ve been celebrating diversity on the pages of Writer Unboxed, and there’s nothing more unique to a writer than their authorial voice. But what is it, exactly, and how can you find yours? Is it the narrative voice? A character voice? The voices in my head? Yes, and no…and yes.

Read More