Diversity

Michael Zapata’s ambitious debut novel, The Lost Book of Adana Moreau (Hanover Square Press/HarperCollins) meanders back and forth in time, across continents, languages, and dimensions, as one of the main characters, Saul Drower, searches for the owner of a mysterious novel manuscript that his recently deceased grandfather had promised to deliver. Clues to the mystery reveal themselves via stories within stories, a vague introduction to theoretical physics, meditations on the climate crisis, and delicious references to science fiction classics. As all the stories within stories knit themselves together, Saul tracks Maxwell Moreau, the son of the manuscript’s author, to post-Katrina New Orleans where they confront the meaning of their journeys and their connections to those who came before them.

Mike is a founding editor of MAKE Literary Magazine and the recipient of an Illinois Arts Council Award for Fiction, the City of Chicago DCASE Individual Artist Program award and a Pushcart nomination. As an educator, he taught literature and writing in high schools servicing dropout students. He is a graduate of the University of Iowa and has lived in New Orleans, Italy, and Ecuador. He currently lives in Chicago with his family. His book has already been praised in The Chicago Tribune, The New York Times, The Washington Post, Kirkus Reviews, and other publications.

I was lucky enough to talk to Mike the morning his book launched. He was generous with his insights and his time, which was a real gift because I had a lot of questions about this enchanting novel.

Julie Carrick Dalton: Mike, welcome to The Writer Unboxed. As you know, I’m a huge fan of your book, in part because you take such big risks with structure. You incorporate many complex elements, yet, somehow weave them together beautifully into an un-put-downable story. What inspired you to take on such an ambitious structure in a first novel?

Michael Zapata: The structure definitely emerged sentence by sentence. That said, I have spent a lot of time thinking about the Latin American literary tradition. The structures found in Latin American literature can be so extraordinary, and I think they allow for some of these divergent elements of stories within stories. There’s a long tradition of that. I put a challenge to myself to combine that with the North American structure that is more plot-heavy, concerned with getting from point A to point B. Overall, I wanted to combine a Latin American structure with a North American structure and see what would happen.

JCD: It occurs to me that a reader could tease The Lost Book of Adana Moreau apart, restructure it, and present it as a book of fables. The story of the Dominicana and the pirate, the story of the pony and the mine, the story of the Lost City, and so many others embedded within your larger narrative. I’m in awe of how you pulled this off. Did you take inspiration from other authors who employ stories within stories?

Read MoreElizabeth’s marketing at work.

For my final installment of my Author Up Close series in 2019, I’m sharing a Q&A with Elizabeth Bell. Elizabeth and I e-met after both finaling in a writing award competition. Elizabeth is a craft genius—no surprise there; she has an MFA from George Mason University and works in the school’s library. When I caught up with her she was launching her novel, Necessary Sins, a James Jones First Novel Fellowship finalist. Her 26-year journey to publishing is fascinating, and our Q&A provides an honest look at the sometimes tumultuous road to publishing and how that road makes it even more important to define success on your own terms.

GW: You’ve got an interesting backstory when it comes to writing Necessary Sins, including how long you spent working on it. Will you share what inspired you to write about this particular subject?

DB: When I was eight years old, I visited Charleston, South Carolina. I fell in love with its gardens and architecture and wanted to set a story there. As an adolescent, I devoured Colleen McCullough’s The Thorn Birds, John Jakes’s North and South, and Alex Haley’s Roots. I wanted to write a saga on that scale, something with multiple settings that would follow characters across decades. Those stories are great escapism and drama, but they also taught me about history and place.

The central family in my saga, the Lazares, is multiracial and “passing.” This was partially about secrets—family sagas always revolve around those—and partially about history, getting at the heart of the contradictions that are the American Dream. But the very first seed of the Lazares’ racial makeup came from my mother. She read an early draft and told me Caucasian people don’t have black hair; it would have to be dark brown. But my Lazares had black hair; I just knew it! Caucasian people do have black hair—the Welsh, for instance—but somehow the “problem” of black hair simmered in the back of my mind. I was puzzling out David’s (one of the main characters) personality, what made him reluctant to trust and reveal his true self, as well as why his uncle Joseph might choose to become a celibate priest. Joseph is very pious, but as a priest, he’s also hiding in plain sight. My characters are products of their time, but I wanted them to resist racism. What might make them view the world differently than the slaveholders around them and work for justice? My answers to these questions coalesced into the Lazare family having African ancestry.

It’s taken me a quarter-century of research and revision to become a wise enough person and good enough writer to tell this story.

GW: You went to great lengths to authentically portray characters with African ancestry. Will you share some of the things you did to help with that?

Read MoreStonewall Inn – Jun 21, 2019. Photo by John J Kelley

Fifty years ago, when I was but a toddler in a bayou town along the Florida Panhandle, an uprising at a nondescript Manhattan bar changed my life. On Jun 28, 1969, patrons of Stonewall Inn, a hangout for some of the city’s most marginalized populations did the unexpected, striking back rather than complying when police raided the establishment. For reasons even participants could never fully explain, frustration and anger from years of ongoing harassment suddenly erupted. Over the course of several hours, what began as a clumsy operation to clear the bar grew into an open rebellion, drawing hundreds to the streets of Greenwich Village in protest. When the dust settled two days later, the queer community found an instant rallying point which would propel its members from the closet to the front lines of an ongoing civil rights movement.

But public incidents, no matter how epic they may feel in retrospect, rarely change any given individual’s mind or touch one’s heart. As a child of the Deep South, I wouldn’t even hear of Stonewall until two decades later. So while I am grateful for their act of defiance all those years ago, and for the many struggles – and successes – that followed, stories from Stonewall were not key to my personal evolution as a gay man, at least not emotionally. That I owe to the talents of a writer on the opposite coast a few years after the events of 1969. That man is Armistead Maupin, and the weekly serial he crafted for readers of the Pacific Sun and later the San Francisco Chronicle became the beloved Tales of the City book series.

CC BY-SA 3.0 – Stonewall Inn 1969, Diana Davies, copyright owned by New York Public Library

Coming to terms with my sexuality while serving as an Air Force officer, Tales offered a glimpse of a world in which being gay need not define me, dictate some hopeless fate or dominate my thoughts as it so often did at the time (the closet can be like that). Maupin’s characters were funny and flawed and imminently human, living their fullest lives with zeal. And though the narrative was as breezy as a beach read, when it dove into deep emotion, the words rang true, offering profound insights on the human condition. In ways I didn’t realize at the time, his stories gave me a blueprint for how life could operate if I opened my heart and let myself breathe. In essence, his writings gave me the freedom to be myself.

Great stories can do that. They open a window to a broader world and provide a microscope for examining our innermost feelings. Now that I am a writer as well, one still striving to achieve Maupin’s skill at developing a compelling cast of characters with tightly woven arcs, I have a theory that every writer has an “origin source,” the read that first opened their eyes to who they are or aspire to be, and which act as touchstones through the years. To explore my premise […]

Read MorePainting of Dido Elizabeth Belle (l) and her cousin Elizabeth Murray (r), circa 1778

I start this call to action with a confession. I began writing my first historical novel, The Magician’s Lie, around 2009. After multiple rewrites, working with my agent and an outside editor, we finally sold the novel to Sourcebooks in 2013. After more work and more rewriting, the book was published in January 2015. I estimate I must have done no fewer than 10 complete revisions, in which I overhauled nearly every aspect of the story: plot, character, timeline, scene breaks, chapter breaks, language, perspective, and countless other elements of the novel.

And at no point during that process do I ever remember thinking, You know, maybe there should be a character in this book who isn’t white.

Now, this seems vaguely ridiculous. White privilege is a reason, not an excuse, and as an American-born white writer I have benefited from that privilege. I’ve had the luxury of not thinking about things like, oh, whether this aspect of my writing reflected either today’s world or the world in which my story was set. I haven’t had to consider whether agents or editors will be interested in stories about people who look like me: overwhelmingly, they look like me.

If you’ve been following publishing at all, you probably know there’s an active, powerful #ownvoices movement advocating for stories in which the protagonist and the author share a marginalized identity. And that’s awesome.

What I want to advocate for here is something different. Not every writer is equipped to take on a book with a marginalized protagonist; not everyone has that kind of story to tell. As allies, white writers can support, promote, purchase and read stories that bring racial and ethnic diversity to the fore. Same goes for stories from other marginalized communities and identities. Find them, love them, talk about them. It’s all the same stuff we ask our readers to do for our stories; it’s the least we can do to encourage stories we want to see in the world.

So if I’m not advocating writing stories from communities outside the mainstream, what do I want historical fiction writers who look like me to do?

More work. More research. Look, I know there’s already a lot. We’re spending hours looking up the menu at Delmonico’s in 1905 and finding exactly the right smart cloche for our fashion-forward 1923 flapper to slap onto her head. We’re digging up slang, addresses, music, architecture and more. The best historical fiction pulls the reader into a world so well-drawn it feels like we’re there with the characters, seeing and tasting and touching that world.

And if you haven’t considered that not every face in that world you’re writing about is white, it’s time to consider it.

I use “white” as shorthand in that sentence but it’s about far more than race, obviously. Neurodiversity. Disability. Gender expression. So much more. People with marginalized identities have always existed; history books and Hollywood have created the illusion that they didn’t. Especially in the past few years, historical fiction has become a key tool to make the untold stories […]

Read More

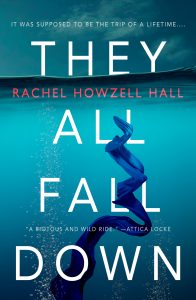

I heard of Rachel Howzell Hall long before we actually met. I had been told by friends about her Elouise “Lou” Norton novels based in South Central Los Angeles, and found them every bit as smart, grounded, and compelling as advertised. Then I read her now famous 2015 essay, “Colored and Invisible,” where she discussed being one of the few black writers at annual mystery conferences. (This was the inspiration for a six-writer roundtable in Writer’s Digest on the issue of being a writer of color in the crime genre.)

Finally, Rachel and I met face-to-face in 2017 at the Writer’s Digest Novel Writing Conference in Pasadena, and were on a panel together where her self-effacing humor, gracious charm, and [insert superlative adjective] intelligence were impossible to ignore. I got on my knees and begged her to be my friend. (Not literally, but close.)

I also began working to get her to join us at the Book Passage Mystery Writer’s Conference in northern California, where she appeared in 2018 and was so popular with the participants we’d like her to be a permanent fixture—ahem, I mean tenured faculty member—if she’ll have us.

That may be hard, because she’s going to be in high demand now. Her latest novel, They All Fall Down, a standalone thriller that came out three days ago—based loosely on Agatha Chriustie’s iconic And Then There Were None—has been getting sensational reviews (“”[A] master class in strong, first-person voice”–New York Journal of Books), and it just may be that her twenty-year slog to Overnight Success may finally have paid off.

Here–let her tell you about it.

You didn’t start out as a crime-mystery writer at all. What were your first efforts in fiction, and how did that turn out for you?

No, I didn’t start out as a crime writer, but my stories always included elements of the genre—people doing bad things to each other and someone trying to understand motives. I always wrote worlds that were ‘off,’ but back then, I didn’t know to label it as ‘crime.’

In my first published novel A Quiet Storm, there’s drama, psychological suspense and a disappearance. The question that threaded the story was, ‘What happened to Matt?’ And, of course, if I wrote that story now, it would probably have the point-of-view of the detectives who, as it stands, make relatively minor appearances in the story.

But I liked the crime and mystery part of the story the most, I just didn’t know how to pull it off while also figuring out my voice. This led to a period in my career where I couldn’t sell a thing because I liked darker material, with black characters, with my odd sense of humor. Editors didn’t like it, couldn’t figure me out. Some were offended by my humor and some didn’t think my stories were ‘urban’ enough.

Rejection became as common as pigeons to me but while I flirted with the idea of quitting, I didn’t. I let those hours of dejection and depression pass and I went back to it. In the meantime, two of my rejected novels were self-published on Amazon. While they weren’t perfect, the stories are solid […]

Read MoreFlickr Creative Commons: Robert GLOD

I’ve spent my life living between India and the U.S.A. One blog post can’t begin to describe the challenges, privileges, lows, and highs of it all. I can, however, talk about being a bi-cultural writer and writing in various global dialects through one language. I am a weird kind of third-culture kid. I was born in the U.S and finished elementary school there. Then I did middle and high school in India and returned to the U.S for another 8 years where I finished college and my Master’s degree. I’ve since been back to Bangalore, India since 2011.

First, let me tell you about my accent. I code shift – my accent and cultural references can change according to country, and who I’m talking with. I still get teased about it.

Because of my experience, I see English as two very different kinds of languages: Indian English and American English. On the macro level you might think it’s just the accent that’s different, but there are more nuanced differences that are a result of specific cultural backgrounds and responses to very different realities and environments. I admit, it’s easier for me to write for a specific cultural audience. That’s why I’ve been involved with the way I think about writing for a global audience. How do I hold a place in a specific narrative and allow for people from all kinds of backgrounds to find a point of similarity to their own reality? Over the years, I’ve done a lot of relearning and decolonizing. Here are 3 important things I have learnt as a bicultural writer.

Letting Go Of Italicizing Culturally Specific Words

Growing up, I’d read Indian authors italicize or explain very Indian terms in strange ways. I acknowledge that for many non-Indian readers, if I made one reference too many to terms or concepts uniquely Indian, I would risk losing them, and worse, boring them. That said, using western-centric explanations and using italics takes away from the authenticity of the environment. I’d read ‘samosa’ with descriptions like seasoned potato filled pastry, and I’d chuckle. This is not because the description is inaccurate; in fact, it is probably the best way to explain what it is in English to a western audience, but it’s not how people raised in India would think of it.

I found authors who were owning their language with the English they spoke, offering more of a realistic picture of life in such a setting. Many Indians grew up reading British and American books with descriptions of food items we had never tasted in the 80s and 90s, and we had to make do with the names and imagine what they were. In fact, my father had grown up reading Archie Comics in India and assumed pizza to be a sweet dish. When he came to America in the late 70s he was shocked that pizza was savory! We never got explanations and we’re probably all the richer for it. While the world is a lot more globalized now and many readers are more exposed to cross-cultural habits and foods, there are still things that will be very specific to a culture and environment. It’s also the age of […]

Read MorePhoto by Pexels via Pixabay Free License

Recently my latest creative pursuit, a departure from my stalled work in progress, has started bumping against a writerly controversy about which I had previously been only vaguely aware, that of authors receiving sharp pushback on their characters and in some cases their entire story concept because of perceived cultural disrespect or disregard. And though my pursuit has to date been a personal one, I still found myself chafing under what at first seemed arbitrary and potentially insurmountable barriers. You see, my current exercises involve crafting scenes in which I seek to embody characters unlike myself, with life experiences far removed from my own. In doing so I imagine their worlds, borne of research and admittedly from instinct too, as with any fiction. On one level the exercise is simply a creative challenge. But it is has also become an emotional touchstone since my attempts to “walk a mile in their shoes” have reawakened my empathy in an increasingly isolating world. Makes for good stuff, huh?

You would think so, or at least I did. But my joy in this new pursuit has since tempered. You see, last week I stumbled upon a New York Times article about author Amélie Wen Zhao withdrawing her debut novel, Blood Heir, from publication following accusations of insensitivity and outright racism in her portrayal of a fantasy world in which characters born with special powers are enslaved. Though Zhao, a Chinese immigrant, has explained the inspiration for the novel stemmed in part from largely overlooked indentured servitude prevalent across Asia as well as her personal experience as an outsider, criticisms soon overtook the initial positive reception of advance readers, leading to her decision to withdraw the novel prior to its scheduled June release.

Not having an advance copy myself, I cannot assess the full veracity of the complaints. Yet the situation immediately struck me as unfair. After all, an author chose to forego a publishing dream pursued for most of her young life right at the cusp of its fruition. In the days since, I have devoured reports of other recent works withdrawn from publication, both before and after their market releases. And though I now have more insight into the issues at play, my feelings remain torn. So I turn to you, fellow Unboxers, to help unravel the decidedly thorny matter of the degree to which writers should shape their creations to meet the expectations – or demands? – of potential readers.

Read MorePhoto “face time-2” by Albyn Davis

No, this isn’t about writing dishonestly. Quite the contrary.

I’m returning to a topic I’ve touched on before, but with a different slant this time around. Please bear with me.

We live in an era of such extreme social and political division that if often seems tensions cannot resolve without matters coming to blows—or blood. The increasing number of mass shootings underscores this point, as does online acrimony and the testimony of virtually every retiring senator, regardless of party, that something is broken in our current political culture.

Writers are not in the division biz. We’re in the understanding biz. Every book in some sense attempts to address a truth that the writer felt was previously overlooked, undervalued, or misunderstood.

Truth, though, is a tricky critter. It conjures analogies to greased pigs and invisible songbirds.

Let me lay my cards on the table: I do not believe truth exists objectively, like this desk in front of me or the moon. I’m schooled in this position by a long line of American Pragmatists, most notably William James, John Dewey, and Richard Rorty.

James famously said, “What’s true is what works,” and earned the eternal scorn of European philosophers whose belief in truth was very much grounded in Platonic and Kantian idealism and mathematical certainty.

But James’s point was really quite profound. He was implicitly asking: How do we know something is true? And his response was: When we use it, we tend to be more successful than not.

So when I say a book—and for our purposes here, I mean a work of fiction—attempts to address a truth previously overlooked, undervalued, or misunderstood, what I mean is that the writer, in posing the crucial story question, What if…? in some way hopes to show that certain ways of acting in the world—whether believed to be conventionally “right” or “wrong”— achieve their desired ends or don’t.

Does courage always win the day? Honesty? Love? Faith? Family? Or are we better off embracing skepticism, enlightened (or naked) self-interest, moral flexibility, violence, power? Is there a middle ground? If so, who does it favor? Do we, as novelists, even have to decide? Or is our job to show how all of these inclinations collide and interact and contaminate each other in the endless scrum known as human life?

Milan Kundera, in The Art of the Novel, refers to “the fascinating imaginative realm where no one owns the truth and everyone has the right to be understood…the wisdom of the novel.”

Fair enough. But how do I honestly go about creating and portraying characters whose beliefs are not just different from mine, but utterly repellent to me?

Read More