Diversity

Among the many powerful things I’ve read recently, the one that struck deepest as a writer of fiction came from Robert Stone’s piece in Paths of Resistance: The Art and Craft of the Political Novel. The piece was titled “We Are Not Excused,” and the section in question was this:

The practice of fiction is an act against loneliness, an appeal to community, a bet on the possibility that the enormous gulf that separates one human being from another can be bridged. It has a responsibility to understand and to illustrate the varieties of the human condition in order that consciousness may be enlarged.

The writer who betrays his calling is the one who, for commercial or political reasons, vulgarizes his own perception and imagination and his rendering of them … The reassurance [such writing] offers is superficial: in the end it makes life appear circumscribed. It makes reality appear limited and bound by convention, and as a result it increases each person’s loneliness and isolation. When the content of fiction is limited to one definition of acceptability, people are abandoned to the beating of their own hearts, to imagine that things which wound them, drive them and inspire them may be a kind of aberration particular to themselves.

Stone’s remarks reminded me of something Simone de Beauvoir wrote in a review of Violette LeDuc’s memoir, La Bâtarde:

She who writes from the depths of her loneliness speaks to us of ourselves.

Finally, I was also reminded of the philosopher Richard Rorty’s concept of ironism, which can be described as “fashioning the best possible self through continual redescription,” an effort that requires us to reach beyond our own experience to learn from the experiences of others—in no small part from reading and writing. This is how we create solidarity:

Solidarity is brought about by gradual and contingent expansions of the scope of “we;” it is created through the hard work of training our sympathies … We train our sympathies … by exposing ourselves to forms of suffering we had previously overlooked … to sensitize [ourselves] to the suffering of others, and refine, deepen and expand our ability to identify with others, to think of others as like ourselves in morally relevant ways. The liberal ironist, in particular, sees “enlarging our acquaintance” as the only way to assuage the doubts she has about herself and her culture.

The task of achieving solidarity is … divided up between agents of love (or guardians of diversity) and agents of justice (or guardians of universality).

I doubt I’m alone in taking heart from thinking of “guardians of diversity” as “agents of love,” though it is also disturbingly clear that this is a view currently under strenuous attack.

My point here, however, given that it’s Valentine’s Day, is to broaden our understanding of love as it pertains to the stories we write, and why we write them.

I imagine it seems somewhat counterintuitive to think of fiction that conforms to convention as enhancing a sense of loneliness or isolation. The whole point of writing in a conventional manner is to be popular, to gain as wide an audience as possible. Stone’s point is that this is an act of bad faith, […]

Read MoreGreetings, WU Family. In my first post of the year, I’m introducing you to Ann Michelle Harris. Ann Michelle is an attorney by day, and at night, she writes romantic suspense and fantasy/speculative fiction with diverse characters and positive social justice themes. In today’s Q&A, she shares how her work in the areas of poverty, abuse, and child welfare guides her, how that work inspired her novel, North, and why she feels building community is one of the most important things a writer can do for their career.

GW: One of my favorite parts of this series is learning about an author’s origin story: the thing that propelled you from someone who only thought about writing to someone who actually wrote and has a book out. So, what’s your author origin story—in other words, why did you start writing and keep writing?

AMH: I have loved reading adventure stories since I was very young. I was an English major at Penn so I loved not just stories but also story analysis, themes, and structure. Several years ago, I went through a stressful time in my life and began immersing myself in escapist stories as a form of comfort. After months of consuming other people’s stories, I decided to become a contributor of short stories to a public writing forum. Positive responses convinced me that I might have a larger story worth telling and that I could be brave enough to take the risk to try to tell it. I specifically wanted to write an adventure story in honor of my children. Shortly after this, the pandemic came and gave me even more stress but also much more time to write since I no longer had to spend hours commuting to the office each day (and it gave me plot inspiration). That extra time allowed me to dig deeper into creating a full manuscript and begin the process of querying.

GW: Can you tell us about your path to getting North published?

AMH: After completing my manuscript, I began to query it to a few agents and independent publishing houses. I got rejections, but one rejection from a large indie press had detailed feedback about the plot (particularly the ending) and that helped me tweak some elements. I also worked with a developmental editor, a beta reader, and a critique group to fine-tune the scene structure and build more tension in the story arc. By then, I had heard from a few writers that it is sometimes more accessible to directly find a publisher than to find an agent. I had another historical gothic manuscript that was getting a lot of traction with agents, but I decided to pitch North to a small press at a writing conference, and they loved it after reading the full story. After I signed the publishing contract, I continued to fine-tune the manuscript and then worked with the publisher for editing, galleys, and cover design. I tweaked everything until it was ready for submission to the distributor, and then finally it went into pre-order. I used my pre-launch time to promote the book online, connect with readers, and lean heavily on the wisdom of my more experienced writer colleagues, who were incredibly supportive. Then the big day came […]

Read MoreI’m guessing, given Tuesday’s election, most of us have been living in a world of, shall we say, heightened reality the past few days (if not weeks, or months). So, with no desire to diminish the importance or impact of that reality, allow me to offer a bit of a diversion, one I’ve had planned for some time: here’s an interview with Rachel Howzell Hall, known for her bestselling thrillers, about her turn to romantic fantasy with her latest book.

Rachel has been on a bit of a tear lately: her most recent previous novel, We Lie Here, was both a bestseller and nominated for a Los Angeles Times Book Prize. Before that she had three bestsellers in a row, What Fire Brings, What Never Happened, and These Toxic Things (also nominated for the Anthony Award, the Strand Critics Award, and the Los Angeles Times Book Award), with And Now She’s Gone garnering nominations for the Lefty, Barry, Shamus, and Anthony Awards.

With so much success in the thriller category, why jump ship and climb aboard an entirely different genre? I asked her that question (see below).

Meanwhile, The Last One, which comes out December 3, has garnered significant pre-publication praise:

The Last One can be pre-ordered now at Bookshop.Org, Amazon, B&N, Google Books, Kobo, Apple Books, or at your favorite local bookstore.

How did your agent (and/or editor/publisher) respond when you proposed a book so different from your past work?

Actually, it was my agent Jill Marsal who first reached out with the possibility of collaborating with publisher Liz Pelletier. I was thrilled at the opportunity—Liz is a genius. She was preparing to launch a new imprint from Entangled called Red Tower, filled with high-concept ideas she wanted to bring to life. I was honored to be one of the writers she thought would be a good fit for the project.

I get the feeling that this is a book you’ve been wanting to write for some time—have I got that right? If so, what kept you from getting to it sooner? How long did it take to imagine it, plot it out, and then get it down on the page?

I didn’t realize I wanted to write this book until I actually started. I was pretty intimidated by the idea of tackling not just one, but two new genres. I had never written a romance, and I had never written a fantasy. However, I soon discovered that I still had a lot to say—things I’d expressed before in mystery and crime—but now I had the opportunity to explore them in a world I could entirely create. A world without rules, until I made them.

I was offered the opportunity in July 2022 and began writing. I […]

Read More

“The first rule of Fight Club is: you do not talk about Fight Club.”

Fight Club, the book and the movie, comes at you like a right hook. In my experience, you love it or you hate it. But unless you’re tragically hipster or a Gen Z nihilist, the last thing you are is ambivalent.

Which brings us to the topic of today’s post.

Welcome to the Suck.

I’ve been in the publishing industry for nearly 25 years. It’s always been the Wild West. Lately, though, it’s been looking less like a Western and more like a post-apocalyptic dystopia. We went from High Noon to The Hunger Games in six seconds flat.

In this landscape, your story is either a Sherman tank, or a ghost.

“One size fits all” fits no one.

I can’t tell you how many writers I’ve talked to who say their story “could appeal to everyone… anyone from age ten to seventy, any race, any gender, any walk of life!”

No, it really, really doesn’t.

Because nothing appeals to everyone.

Hell, I know people who don’t like pizza, and if that’s not proof there is no universally appealing thing on earth, I don’t know what is.

More importantly, appealing to everyone should never be your goal when it comes to writing, especially now.

“Universally appealing” generally means average, safe, standard.

That’s DMV beige. That’s unseasoned boiled chicken breast.

That’s ghost territory.

Turning it up to eleven.

It started with the rise of the internet, when a plethora of images, information, and interaction were suddenly, literally at your fingertips. Ironically, in a time where we have the largest buffet of brain candy in the world, people are starving for all the choices.

(If you’ve ever spent an hour perusing Netflix titles while choosing nothing, you know what I mean.)

As a result, it takes something truly vibrant, amplified, and dare I say polarizing to connect with the right readers… the ones who will not only love your work, but spread it like an underground rebellion through their various whisper networks.

In this environment, “meh” is the enemy. Ideally, you want people to either love it or hate it, but by God, they have strong feelings either way.

That’s what we’re looking for. Strong feelings.

But how do you do that?

Repeat with reader experience. Think about what draws readers to your genre. For example, in mystery, they love the puzzle, the challenge. They want the clues, the twists, the red herrings. They want to feel smart, but challenged. They want to know they could solve the murder – but still be pleasantly surprised at a fair, believable, yet unexpected finale.

Add depth to […] Read More

In my senior year as a math major, I scored second from the top of my class in the theoretical aspects of advanced analysis (calculus squared, as it were) and fifth from the bottom in the practical applications of the same material.

The head of the department, Dr. Arnold Ross (born Chaimovitch)—a man who profoundly influenced me in numerous ways—took me aside and said, “You want to be a philosopher, not a mathematician.”

He wasn’t wrong, though I ultimately became neither. But my philosophical disposition has revealed itself in both my reading and writing.

Although we speak often and at length on the importance of making sure our readers feel something, I personally cannot commend a novel that does not also make me, in the words of Dr. Ross, “think deeply about simple things.”

Some of you may remember a post I wrote for Writer Unboxed a year and a half ago titled, “Writing Our Country.” It sought to apply some of the ideas of the American neo-pragmatist Richard Rorty to writing fiction in today’s literary environment.

Specifically, the post addressed Rorty’s belief that the novel served a uniquely valuable role in expanding not just the perimeters of our understanding but the range of our empathy for others whose backgrounds, cultures, and daily experiences vary widely from our own.

The goal of this expansion was to broaden the range of solidarity of human beings seeking a more just, prosperous, and peaceful world.

The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy puts it this way:

The key imperative in Rorty’s ethico-political agenda is the deepening and widening of solidarity … [He] distinguishes between “us” and “them,” arguing that thinking of more and diverse people as “one of us” is the hallmark of social progress. Solidarity is brought about by gradual and contingent expansions of the scope of “we;” it is created through the hard work of training our sympathies … by exposing ourselves to forms of suffering we had previously overlooked. Thus, the task of the intellectual, with respect to social progress, is not to provide refinements of social theory, but to sensitize us to the suffering of others, and refine, deepen and expand our ability to identify with others, to think of others as like ourselves in morally relevant ways.

As self-proclaimed “postmodernist bourgeois liberal”:

[Rorty] is skeptical of political thought purporting to uncover hidden, systematic causes for injustice and exploitation, and on that basis proposing sweeping changes to set things right. Rather … [he] follows Judith Shklar in identifying liberals by their belief that “cruelty is the worst thing we do,” and contends it is our ability to imagine the ways we can be cruel to others, and how we could be different, that enables us to gradually expand the community with which we feel solidarity.

For Rorty, the novel plays a uniquely valuable role in this effort:

Novelists, like Vladimir Nabokov, George Orwell, Charles Dickens, Harriet Beecher Stowe, and Radclyffe Hall, offer new descriptions that draw our attention to the suffering of previously overlooked people and groups. They contribute to social progress by pointing out “concrete cases of particular people ignoring the suffering of other particular people.” Because reading novels is one of the best ways to sensitize […]

Read MorePhoto courtesy of Lost Places

As so often happens, last month’s comments section inspired this month’s column.

The commentor had written a fantasy story for a competition, and in order to create a sense of a strange and exotic world in as little space as possible, pulled a number of details from ancient China. The judges liked the story but ultimately rejected because they felt the commentor was writing about a culture not her own. As the judges said, great writers had done this in the past, but “nowadays, ethnicity and authenticity are more significant.”

So . . . when it is appropriate to create characters who belong to another culture or race or gender or orientation – someone with very different life experiences from your own?

First, a caveat. I am a 63-year-old straight white man who grew up in a thoroughly homogeneous culture – Wyoming Valley, Pennsylvania. Nearly the entire population was white, primarily settlers from Connecticut and Philadelphia overlaid with immigrants who came over from eastern Europe in the nineteenth century to work the mines. A mixed marriage at the time was Polish Catholic marrying Italian Catholic. I’ve never had to worry about the possibility of being shot during a traffic stop or that my family would cut off contact because I fell in love with the wrong person, and I’m sure I take that privilege for granted.

But given that caveat . . . part of the art of writing is putting yourself in someone else’s head. It should be possible to do that even with a character who has had very different life experiences from your own. That is, after all, what imagination is for. Abandoning this approach to fiction is what gave us the old joke about MFA programs producing a lot of first novels about MFA students struggling with their first novel.

On the other hand, stretching your imagination too far can present some dangers. Cultural appropriation is a thing. If you try to place your story in a culture different from your own or center your dramatic tension on the hardships faced by characters very different from yourself – i.e. write about experiences you haven’t lived – you run the risk of being shallow or exploitative or both. How do you put yourself in the head of someone very different from yourself without offending the very people you’re writing about?

First, this largely applies to realistic stories set in the modern world. If you’re writing from the point of view of a twelfth-century French peasant and get the attitudes wrong, you’re only going to upset a group of medieval historians. If you’re writing from the point of view of a methane-based floating jellyfish living in the clouds of Jupiter, then you don’t have to worry.

And most of the time, the question never arises. Most writers base their characters on themselves, so they tend to not stray too far from their lived experience to get their stories told. But sometimes, for dramatic reasons, you’re called on to write about someone who is further from yourself in critical ways. What should you watch for?

Back in 1999, I read an article in The Atlantic Monthly that stuck with me: “ Read More

In Havana. Image – Getty iStockphoto: Nadezdastoyanova

‘Workquakes’ and Other Influences

I had looked at Bruce Feiler’s new book The Search: Finding Meaningful Work in a Post-Career World (Penguin Press, May 2023) to find a statistic I’d heard Feiler mention in an interview. It’s not the pandemic that triggered so many job changes for so many people. In the United States, the numbers have been rising since 2012.

“A third of the workforce now leaves their jobs every year,” Feiler writes.

It was the next sentence, I discovered, that was even more interesting: “Another third redesigns the jobs they’re in. They assert more influence, work more remotely, dial back hours to spend more time with family, dial up flexibility to pursue side work that brings them purpose.”

Feiler uses a couple of phrases especially good at helping writers think through their work and, more to the point, their relationship to it. Your “work story” is “an ongoing, unspoken narrative that we’re constantly revisiting and revising in response to changes in our jobs, our families, and our lives.

And a “workquake” is an interruption: “We face a never-ending barrage of interruptions – some voluntary, others involuntary; some unique to us, others shared by the entire planet; some that grow out of changes in our workplace, others that grow out of changes in our mindsets.” By his estimate, as many as 80 million Americans are in a “workquake” at any given moment.

Knowing that women make up the largest gender group regularly reading Writer Unboxed, I’ll highlight something else that Feiler surfaces in the research he’s done for this book. It has to do with some of the major writings about career we all have fallen asleep trying to read.

In Stephen Covey’s 1989 The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People, Covey “spotlights 56 white men, two white women, five Black people, and two minorities,” Feiler writes. Richard Nelson Bolles in his 1970 What Color Is Your Parachute? Mentions 85 white men, no women, no Black people, and no minorities.” Probably the grandfather of them all, Dale Carnegie’s 1936 How To Win Friends and Influence People “features 252 white men (including Jefferson Davis), 24 white women, no Black men or women, and two minorities.”

Apparently, one way to win friends and influence people is to be white and male. I’m here to tell you it doesn’t always work, but that’s a different article. The social eras and contexts in which those books were written come into play, of course, as do other factors. But I bring these points up – Feiler has many more – because those demographic elements alone can have something to do with the way we think of our work and our writing.

And is it your work’s place in your writing that counts? Or is it your writing’s place in your work? Put more plainly, what if they’re not one in the same?

What if your career isn’t … the books?

The Orangery on the Hill

Provocations graphic by Liam Walsh

The phrase “work story” makes sense to me because I’ve seen mine change dramatically over the years. What attracted me to Feiler’s The Search, though, has to do with the fact that my writing has changed, too […]

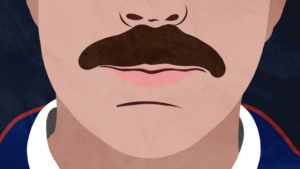

Read MoreThe Apple TV show Ted Lasso has been mentioned here before, most notably in this post by former WU regular Bill Ferris, who spotlighted the show two years ago. But staying true to my lifelong habit of being woefully behind the times (I still haven’t gotten around to seeing that new Kevin Costner movie, Dances with Wolves), I was late to the party in joining the sizable fandom of All Things Lasso.

I’d been hearing about Ted Lasso for a while, but had been dragging my feet about checking the show out. For one thing, it appeared to be about sports. I not only don’t care about sports; I actively dislike them – a holdover from my teenage days when I resented all the attention that high school athletes received, while musicians and other artists were largely ignored. (Yes, I am an attention slut – why do you ask?) It also sounded like a pretty goofy fish-out-of-water premise: an American college football coach who suddenly finds himself transported across the Atlantic to coach a professional English soccer team. So it seemed the level of suspension of disbelief the show would require was already taking this into shark-jumping territory. And then there was that ridiculous ’70s pornstar mustache I kept seeing in photos of the titular character. No, this clearly did NOT look like AKVF (Acceptable Keith Viewing Fare).

I also didn’t like the idea that I’d need to subscribe to yet another streaming platform to watch this show. I’m already shelling out money to Amazon, Netflix, Paramount, Disney, and maybe a couple more. But I couldn’t find any other way to watch this show without subscribing to Apple TV. So I grudgingly signed up for one month, figuring I could quickly tell whether this show was worth continuing my subscription.

Okay, I have to admit: Within an episode or two, I was hooked. I went on to binge-watch all the older episodes, and then began viewing what would turn out to be its final season in real time, sometimes waiting an entire excruciating week between episodes (surely one of the most relatable first-world problems of our day). I thoroughly enjoyed the entire series, and was struck by what a unique experience I had in watching this show, so today I thought I’d explore my Love of the Lasso. Okay, that sounds like a pulp fiction paperback title that could have a VERY dodgy cover, so let’s move on and take a look at why this show stood out for me.

NOTE: I’ve attempted to avoid any spoilers, but I will allude to some of the long-reaching themes and concepts the show explores.

First of all, it’s so gosh-darn different.

One of the few upsides of the pandemic – besides allowing many people to work corporate jobs barefoot and in gym shorts – was the quality of streaming TV shows that emerged. But, perhaps not surprisingly, many of those shows explored some VERY dark themes. Ted Lasso stands out among them for having an unapologetically upbeat main character, who is bound and determined to share his own folksy (and okay, often seemingly corny) philosophy with everybody he encounters. As the series progresses, we learn that Ted’s life is not all sunshine and rainbows, but […]

Read MoreOne of the more helpful remarks I’ve read recently in the ever-escalating rhetoric of the culture wars came from historian Thomas Zimmerman:

There is indeed something going on in America, and it does make a lot of people…really uncomfortable. We are in the midst of a profound renegotiation of speech norms and of who gets to define them. And that can be a messy process at times. But it’s not “cancel culture.” From a democratic perspective, it is necessary, and it is progress.

Professor Zimmerman made those remarks in a two-part substack series: Part I: On “Cancel Culture” and Part II: The “Free Speech Crisis” Is Not a Crisis. It Is Progress.

In those essays, he argues that much of the criticism focused on student pushback against speakers and material they deem objectionable largely comes from those invested in the (white male) status quo.

And however disagreeable student actions may be, they are not attempts to use government power to deprive anyone of their free speech rights, which definitely is occurring in multiple locales across the country (more on that below).

Nevertheless, the turmoil generated at Stanford Law School recently, when students heckled and jeered a conservative jurist into silence—only to have a campus administrator, in an attempt to restore order, also attack the speaker and side with the students—has brought the issue of a “free speech crisis” back into the national spotlight. (Unsurprisingly, the situation was far more nuanced than one might be led to believe given the hair-on-fire reactions, as recently reported by Vimar Patel, higher education reporter for the New York Times.)

Heckling, jeering, and outrage are hardly the only examples of the “messiness” Professor Zimmerman is referring to in the quote I cited above. All too often the benign-sounding “negotiation of speech terms” translates into,

Over the next few months I intend to explore multiple ways that speech norms are being “negotiated”—especially as they affect writers of fiction, including:

Each of these reflect the efforts of a certain group or groups to establish—and enforce—guidelines for what can be said or written, by whom, and how.

Put differently, they seek to determine who deserves protection from what is being said or written, by whom, and/or how? At its worst, this becomes: “My moral superiority means I not only don’t need to listen to you, I have the right to silence you.”

All of them are restrictive rather than expansive—i.e., they seek to constrain rather than add to what can be read or expressed. It may seem odd to think of book banning as an attempt to negotiate anything, but the other examples I’ve given also reflect attempts by a relative minority to restrict what can be expressed in accordance with its own moral sensibility.

Everyone in this effort claims to have a laudable purpose in mind: the protection of a group they consider vulnerable (children, families, trauma victims, minorities) from demeaning, shaming, or immoral content; from unpleasant emotions or experiences; or even from discomfort or distress.

As Zimmerman implies, however, given the cultural shift that’s taking place, avoiding distress or discomfort is not just misguided, it’s impossible.

It might instead be better to accustom ourselves to the unpleasant—to value […]

Read More