Posts by Tracy Hahn-Burkett

In 1979, I was a serious ballet student, growing up an hour’s drive from New York City. Devoted to this art, I took classes daily, studied ballet history, the French language (nearly all ballet terms are French), and watched the great dancers at every opportunity. To truly study ballet is to strive for perfection every day knowing you’ll never achieve it, but to love the art form so much that you dedicate yourself to the pursuit of that perfection anyway.

Several times each year, my mother would take me to Lincoln Center in the city to see the major ballet companies perform. I’d get to study the technique and artistry of the finest dancers in the world from the best seats in the theater we could afford. I’d watch the dancers achieve what I could only strive for, and I’d analyze their performances. Afterward, I’d walk to the car on NYC’s sparkling sidewalks, dazzled every time and eager to return to the studio the next day to practice what I’d learned. (I still don’t know what the city put in the concrete to create that glittery effect.)

One August evening that year, we settled into our seats at the New York State Theater to see the Bolshoi Ballet, then one of the top six ballet companies in the world. A day or two earlier, a young Bolshoi principal dancer named Alexander Godunov (whom you may remember as one of the terrorists in America’s most unlikely Christmas movie, Die Hard), had just defected from the company. His wife, also a dancer, had not defected with him, and the Bolshoi immediately put her on a plane to return to Moscow. But the U.S. wouldn’t let the plane leave until they were satisfied that she was returning of her own free will, and as we waited for the ballet to begin, that plane was still sitting on the tarmac. Incensed, the Soviets subjected us to a long political lecture prior to the performance.

As a pre-teen, I didn’t comprehend the finer points of that lecture, but I did understand defections by Soviet ballet dancers and why they happened. Earlier defections by iconic ballet stars Rudolf Nureyev, Natasha Makarova, and Mikhail Baryshnikov had taught me about Soviet artists who were exquisitely skilled but could no longer tolerate the restraints they suffered practicing their art in a society that wasn’t free. Baryshnikov emphasized the artistic versus the political nature of his defection:

“[M]y life is my art and I realized it would be a greater crime to destroy that. I want to work with some of the West’s great choreographers if they think I am worthy of their creations.”

These dancers were my childhood and adolescent heroes. Not only were they the best practitioners of the art I revered, but they taught me that we Americans possessed something of value that only came at great cost to many others: freedom. We were privileged, and other people were willing to sacrifice everything else they had—family, country, every possession they owned—just to access the freedoms we Americans took for granted as our birthright.

Decades later, we live in a different world and a different country. And far too many Americans have become complacent.

I know that many people—perhaps some of you […]

Read MoreLast week, I had to have a tooth pulled. (I know, you’re thinking, “Yes! All great Writer Unboxed posts start with a dental story.” No? Stick with me.)

Now, I’m a bona fide dentophobe, my extreme reaction to any dental procedure caused by a childhood dental trauma. I’m also cursed with terrible teeth, so I find myself in the dentist’s chair far too frequently. And the coping mechanism I’ve adopted for every procedure, from cleanings to root canals, is by listening to engaging novels with the volume turned up high enough to drown out the high-pitched whine of the drill.

This brings me to last week’s procedure. I’d recently begun a dystopian novel whose name I will not share for reasons that will become clear. The novel’s premise intrigued me: What would happen to society if a certain, real, high-tech weapon was used against the U.S.? The author had a military background, and I was curious about how he would depict the aftermath of the weapon’s potential use.

By the time I got to the dentist’s office, I’d already listened to the novel’s beginning, and it wasn’t promising. The characters were uniformly flat, and formulaic. The ex-military guy and his teen daughters. The mother-in-law who gives expensive gifts to her granddaughters and has very definite, regionally based ideas about how the girls should behave. The ex-military guy’s gruff, military pal. The family lives on a mountain with sweeping views that will come in handy in the coming crisis. The early pages were nothing but a set-up that ran on too long, and I became impatient for the actual story to begin.

The inciting incident finally happened, and I thought, Good. The story will at last begin to move while my tooth is being yanked from my head. But my God, these characters were slow. Despite clear signs all around them that the world was amiss, they were at best mildly concerned. They neglected to ask obvious questions. By the time my procedure was done, they still hadn’t even figured out they were in trouble. The most emotional person in the whole story was me.

What is the point of this discussion, besides the result that I was not distracted from the tooth-pulling? I know that the author of this book wrote it to alert people to the dangers of the weapon in question. But though I am still interested in the premise, I’ll need to drag myself back to the novel because of the glacially paced story and the uninteresting characters who, an hour into the audiobook, don’t yet engage with their surroundings in any sort of believable manner, even when they’re faced with a challenge begging to be noticed. In fact, I may be better off just finding a white paper on the topic and reading that instead.

There’s been a lot of discussion about politics in fiction lately, here at WU and elsewhere, and with good reason: politics is everywhere these days. Fiction can be pure escapism, but it also can be a place to explore hypotheticals, to show the world the potential results of evil, and yes, to communicate political messages. Authors have written politics into novels for as long as there have been novels, and you can do the […]

Read More

That was a big detour.

I haven’t been here for a while—for several years, actually. I’ve been away from most creative writing, too; since 2017, my time and my focus have been directed elsewhere. Given an existential crisis in American democracy and my professional background in policy and politics, I felt obligated to do what I could for that cause. So I’ve spent these past years strategizing, planning, writing, editing, teaching, organizing, listening, advocating, witnessing, testifying, leading, going to meetings (goodness, did I go to meetings), and many other things.

But I didn’t write anything that wasn’t political—fiction or nonfiction. And I really missed it.

The crisis is far from over, but some breathing space over the last year-and-a-half has given me a chance to evaluate how unbalanced my life has been without my creative writing practice. I’ve realized that I must come back to it.

But how?

After such a long period away, I knew I couldn’t just take my old WIP off the shelf, open it and waltz through it with a red pen. As I began this new phase of writing, I wasn’t confident about my skills. My craft was rusty. I could write you an op-ed about a wide variety of current events, but that’s not the same as creating a crisp dialogue, a riveting scene or just the right amount of tension in the right places in a narrative.

I needed a plan to bring myself back. So I created a short syllabus for myself, to ground me in craft again and return me to a place where writing creatively feels familiar once more.

This syllabus is one I believe will work for me. While I chose every resource based on my own needs and what I know about the writers/teachers involved, there are of course plenty of other excellent resources out there, as well as lots of ways to do this.

Here’s my program for getting back into my writing practice after years away:

Read More

Do you want to make a difference in the world? Tell a story.

Storytelling is one of the oldest and most effective forms of communication, and we still crave it today. From the earliest days of language, people told stories around campfires. Why? For entertainment, yes, and to be social. But they also told tales to communicate knowledge—to educate, and to persuade. “I want you to understand that you should not go over that mountain ridge. Trust me, bad things will happen.” Such words are not always convincing standing alone. (You know this if you’ve ever tried to instruct a teenager about, well, anything.) But, “Let me tell you a story of the ancient Grandmother from our tribe who ventured over that mountain and met wolves bigger than mastodons; she was never heard from again,” is different. That gets people’s attention. They draw closer and listen. They won’t forget.

If you’re reading this, you’re almost certainly a fiction writer, and you appreciate a good story. You probably can put words and sentences together well. You are a storyteller.

Congratulations. You have the tools to make a difference in the world. Don’t believe me? Let’s take a walk together.

Let’s start in 2016, with the election no one liked. Pretend you don’t know the outcome. Try to think back to late summer, early fall of that year. Can you think of what was missing from the presidential campaigns? (Remember, at this point, you know nothing about Russia.)

There was no Joe the Plumber in that election. There was no couple like Harry and Louise. Remember them? Joe the Plumber originated in the 2008 presidential election—a generic guy who wanted to buy a small plumbing business and who became a short-term conservative hero when he asked then-candidate Obama a question about small business taxes. Harry and Louise were purely fictional characters created in 1993, played by actors, to portray the average fortysomething couple considering various aspects of healthcare reform. They then appeared in television ads on and off through 2009.

Regardless of what you may have thought about these three characters, there’s no denying their effectiveness. The electorate paid attention. Candidates talked about policy and spit out attacks, but these characters offered personal stories to the electorate. They communicated, “Once upon a time I was a person just like you, this is what happened to me, here’s how candidate X would change that, and happily ever after.” (Sometimes it was “unhappily ever after.”) And people responded, “Yeah, I get that. Me, too.” The characters’ stories became short-hand for entire political positions, and for some, the candidates themselves.

Why?

Just as there’s a saying that all politics is local, a lesser-known axiom states that all politics is personal. People want to hear stories that reflect their own experiences, their own feelings, their own future possibilities. This shows empathy on the part of the candidate and lends his or her statements and promises credibility. But that element was missing in Election 2016. Hillary Clinton eventually brought out the story of Miss Universe, Alicia Machado, but it was too late by the time she did. And Donald Trump’s “story” of “forgotten people” (eerily reminiscent of the “forgotten men” in Sinclair Lewis’s It Can’t Happen Here) wasn’t a story. It was a caricature. But […]

Read MoreTrying to solve a problem in your manuscript and you just can’t figure it out? Just say you don’t care and move on to something else.

Yes, really. Stay with me on this one. Let’s say you’ve been working on a problem in your manuscript for hours, days, months, or a lifetime in dog years. You’re trying to write a new piece of it, or you’re trying to solve an old problem in a new way, or you’re working on any scene that requires some creativity on your part. But you’re tired. It’s draft 37 and you’re burned out. You don’t really care how the love interest dies anymore; you just know he needs to be dead in a way that gets to the next plot point and isn’t inconsistent with three other conditions already set up in the rest of the story. Frankly, if you could make him appear to you in the flesh for a moment, you’d hone one of your chewed-up pencils to a super-sharp point and just do the deed yourself. That would feel so good right now.

But that’s not how this works. Now, you’re seasoned enough to know that you can’t wait for your muse to show up before you start to write, so you sit down in your chair, lift your fingers to the keyboard, but…nothing. You can’t figure out the problem. You eat chocolate, and…nothing. You drink copious amounts of coffee. Nothing (except an urgent need to pee). You stare out the window, walk the dog, clean the house… All the usual prescriptions for jogging a writer’s brain add up to you being no closer to accessing the necessary creativity than you were at the beginning of this effort.

So give up. Turn your attention to writing something else.

I’ve discovered that sometimes, when I’m having trouble working through a problem or a scene, I can jog my writing brain into action by metaphorically walking away from my problematic manuscript and instead writing in the form with which I began my writing journey:

Read MoreThat title doesn’t appear to make much sense, does it? You might be thinking, do you even know what those words mean? One is either a plotter or a pantser. If you’re a plotter, you outline. You like to know where you’re going before you set out on your novel’s journey. You may choose to turn right where your outline indicates you will turn left, but that will be a conscious diversion. Order. You must have order.

Pantsers, on the other hand, thrive on spontaneity and the unknown. If you’re a pantser, you just get in the car and drive. You introduce yourself to your characters and let them navigate; you allow yourself to become their instrument. Outlines are like nasal-voiced GPS programs constantly chirping reprimands at you each time you deviate from the pre-approved route. SHUT UP, they make you want to shout. Don’t bother me with directions. I will feel where I want to go.

Me? I’m a pantser. When I write, I always hope to find myself in The Zone, that place composed of buzz and bliss where I forget I’m typing and the words surprise me as they appear on the page, outcome unknown. What do you mean it’s 5:00? Wasn’t it just lunchtime? Whoa, did Sage just drop the key to the whole story in her admonishment to her sister? I didn’t know she was going to do that. Did Michael just die in that accident? Where did that come from? That’s not where I thought this was going, but it’s great. I’m going to follow this trail and see where it takes me.

I may sketch out a few guideposts in advance, maybe identify some oncoming trouble points, but overall, this is how I draft new material. When I complete a draft, I follow the advice of wise author and teacher Jenna Blum: I write a chapter-and-scene outline of the completed manuscript.

“But why outline when you’ve already written the book?” This is a valid question. Here’s why I do it:

Read MoreAnybody else having a focus problem these days?

Silly question. Of course you are. News. It doesn’t even matter where you stand, which side you’re on, or Russia what you believe. The news has captured health care just about everyone’s interest, and for most of us, the climate change ability to concentrate on what we’re writing requires Herculean effort. Because subpoena when the future of our country is at stake, and news is sometimes breaking FBI at the rate of a story every five minutes, most of us, understandably, have discovered NATO we can’t look away. (And let’s not even Trump begin to talk about the additional alcohol and caffeine crazy we’re consuming, the stress eating, budget the lost hours of internet trolls sleep…) Sorry, what was I saying? It’s been a whole paragraph. I had to go check Twitter.

ARRRGGGHHH!

Seriously, let’s talk about focus. Often a problem when we’re bogged down in the clumsy middle of a book, many of us are now experiencing a different sort of distractibility stemming from stress and the fact that we’re living through a more plot-twisty story than anything any of us could have dreamt up. (And one that would have been rejected by almost all editors for its lack of plausibility.) What’s more, unlike the stories we write, this story potentially carries terrifying, generation or longer real-world consequences. It’s the ultimate page-turner. So how do we pull ourselves away from this reality and focus on the worlds we’re supposed to be creating?

The first part of the answer is that you don’t pull away. You accept that you’re going to cede some of your productivity to the news and maybe even to activism, if you’re so inclined.

But you’re probably more interested in part two of the answer—the one that gets you back to your writing. Let writing be your refuge. This constant, high-stress vigilance is exhausting. It’s not where most writers feel comfortable. So no matter how compelling that big world story may be, find a way back to that place of your own creation. Those first few moments in front of the blank page may feel strained, but the people in your fictional world are going to make sense to you in a way the people in the news don’t. Besides, won’t it be a relief to spend time on a regular basis with people whose behavior you can control—at least most of the time? What a great de-stressor, even if you end up not keeping everything you write.

Third, I’m going to share a stunningly simple tool I’ve found works to keep me focused and motivated when writing through the cumbersome sections of my manuscript. Conveniently, it’s also helping these days to bring me back to the page when I feel like my brain is so immersed in the global news vortex I might never be able to retrieve it.

At the beginning of each full draft*, I write on a sticky note a few simple mantras I intend to apply specifically to that draft and place the note where I can see it when I’m working. These mantras can be basic writing precepts, or they might mean nothing to anyone but me. It doesn’t matter so long as they function instantly to direct my attention […]

Read More

Let’s say I’m writing a novel. Heck, let’s say I’m rewriting it. And let’s say this process is taking me an ungodly long time. How long? Let’s not get bogged down in details. This is all theoretical, anyway. I’m hypothesizing for a friend.

Why, fellow unpublished novelist, might this rewrite be taking so long? There are so many reasons: kids, home, work, aging parents, democracy, volunteering in your community, etc. If you want to publish, yes, you need commitment. But you also can’t ignore the rest of your world. Throw in a few life crises, and the process of writing a novel can start to feel like it contains more chapters than the novel itself. Raising a kid? That only takes eighteen years. But a novel is forever.

So what do you do when you feel like every writer you know has finished her seven-book series while you’re still struggling with your debut (or maybe your second or third book)? First, stop beating yourself up. It’s okay. Second, recognize that this abundance of time is an opportunity, especially if you’re unpublished. If you don’t have an agent and publisher tapping their fingers on their desks, expecting you to meet a contractual deadline, then use this time to work on your craft and get that novel right. If all goes well, you may not have this kind of time in the future.

Third, be prepared. If you’re traveling the long road to finishing a book, you may run into a specific set of problems, one or more of which undoubtedly involve you questioning your own sanity. Let’s examine some of these potential anti-speed traps, and see if there’s anything we can do about them.

The gnawing plot problem

You’ve come to a tricky plot point in the middle of your manuscript, and the problem is exacerbated because you can’t give it your undivided attention. Here’s the trap: you’ll solve this problem. Then you’ll solve it again. And again. In fact, you’ll come up with so many solutions to this problem and have so much time to consider each one while you’re tending to your other obligations that you’ll decide each solution seems too contrived to be usable. If it’s not contrived, it’s too obvious, as evidenced by the fact that you thought of it. This is true even if in your literary historical novel set during the American Revolution, it occurs to you that aliens from the Vega star system could thwart the British before they capture the young Patriot by guiding said Patriot to the cache of laser-powered muskets. Duh. Anyone would see that coming.

The solution? Realize it’s possible your perspective has become skewed over time. Yes, you’ve thrown out at least fifty possible plot points. But hopefully you kept a few of the better ones in a “scraps” file somewhere, because chances are at least one of them contained a nugget of something good.

Read More

You never know when you’re going to run into a good writing lesson.*

Last month, team Hamilton released a book about the Broadway show/mega cultural phenomenon, written by the show’s creator, Lin-Manuel Miranda, and Jeremy McCarter, a cultural critic and theater artist who has been involved with the show since its beginning. The book consists of the entire libretto, accompanied by photographs, annotations by Miranda and essays about the show’s development.

I opened the book intending to read it as a fan,** but before long I realized I was reading a class and case study in writing. And while Hamilton is musical theater, many of the lessons scattered throughout the book apply just as readily to writing a novel as they do to writing a musical.

So let’s learn from the masters.*** Here are a few of the lessons tucked into Hamilton: The Revolution. (Note: SPOILER ALERT. You may want to listen to the soundtrack before you read further. Or read a history book.)

Image by Stefan Chinof via DeviantArt.com

How much do you TK? That’s the question.

TK in a manuscript means “to come.” So if you’re writing a scene in a historical novel set in, say, New Jersey in 1777, and you’re missing necessary facts but don’t want to stop writing at that moment in order to find the relevant information, your draft might look like this:

Mary inclined her head toward the parlor, letting him know they were not alone. The [TK-appropriate rank soldier] hesitated, then turned and walked outside. Mary checked the pocket of her skirt again to make sure the [TK-medium for message] was still there, then followed him onto the porch.

You know where you’re heading with the story and what your characters are doing, but you haven’t yet worked out some of the details. So you drop a few TKs and keep going.

Do you TK when you write? Or does writing with TKs make you feel like you’re preparing a savory recipe like Chicken with Forty Cloves of Garlic but omitting the garlic, the wine, the herbs and anything else that contains any flavor? In which case, why bother making the recipe at all?

Read MoreThis post isn’t so much about writing as it is about being a writer. Or, to be more precise, it’s about simultaneously being a writer and a citizen of the troubled world in which we live.

Here’s the question: should the writer of fiction also publicly discuss politics and related controversial topics?

The prevailing wisdom says no. As writers in the twenty-first century, most of us necessarily spend nearly as much time growing and nurturing our platforms as we do writing the books and shorter works those platforms exist to promote. It doesn’t make sense to work as hard as we do to build our platforms only to weaken them by broadcasting our political views. When it comes to political matters, everyone’s got an opinion, and everyone is convinced he’s right. So unless you make your living as a political writer, it’s simply not worth the risk of offending half of the potential readers out there by expressing political opinions we might just as easily keep to ourselves.

But maybe the prevailing wisdom isn’t always right.

I can think of two reasons for a writer to discuss politics with care, and they go hand-in-hand. First, she believes the person she is presenting via her platform is not genuine because the political side of her is a key part of who she is. Second, she believes she has an obligation as a human being to speak up where she sees injustice. In these cases, perhaps it’s better not to remain silent.

Are you the kind of person you want to be? Given your unique skills–which include communicating nuanced ideas to others in ways that resonate–are you fulfilling your obligations not just to promote your work, but to improve whatever it is you value in the world? People look around our troubled planet all the time and wonder how to change it. As writers, we possess a power not shared by everyone: the power of the pen (or laptop). If we write fiction, must we surrender that power completely in order to market successfully our stories and our books?

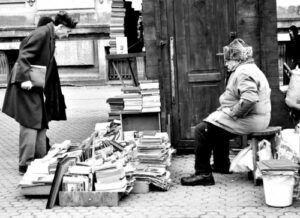

Read MoreI’m going to wear a different hat today than I usually do. (You can’t see me, but I’m taking off my writer’s hat—the one with the red-pencil holder and the built-in chocolate and coffee dispensers—and putting on another hat right now.) I’ve just completed a two-year stint as a part-time bookseller at a lovely independent bookstore. Aside from the obvious bliss of having spent two years surrounded by books and people who love them, I also came away with a new perspective regarding authors and how they approach their close allies, bookstores. I found myself with an excellent opportunity to study both the good and the bad, and I want to share with you what I learned.

Really, everything I’m going to say boils down to one thing: always be professional. This rule applies to all authors, of course. However, I would be remiss if I didn’t share my observation that the majority of the authors I met who needed a helping hand in this area were self-published authors who hadn’t made the necessary effort to understand the business they were entering.

*Write a good book and have it professionally edited. I wouldn’t write this if it didn’t still need to be said. You want your book to be the best book it can be, yes? Someone’s eyes have to be on it other than yours, and I mean someone other than your best friend/mom/spouse/etc. You’ve spent zillions of hours laboring over every word of your book, and you have to know that your eyes at some point glaze over the words and can’t pick up every flaw, every mistake, every typo. You might even miss some structural problems, never mind your personal writing tics. (Did you realize that your protagonist twists her hair over her left index finger every time she gets anxious? That was effective the first two times she did it. But the next thirty? The reader wants to rip her hair right out.)

*Understand that the bookseller wants to carry your book. For some, this might be the most surprising point of all. You and the bookseller are in the same business: convincing the public that it should be reading great books (instead of playing Trivia Crack, taking selfies and goodness knows what else). If the bookseller has a quality product to carry and market, her job is easier. So if you, the author, can approach the bookstore with a superior product–your book–and present it in a manner that demonstrates you understand the business aspect of books as well, you’ll be well on your way to establishing a mutually beneficial and lasting relationship.

*Respect the bookseller’s time and process. You came in and asked how to go about getting the store to carry your book. You were told: speak to a certain person; call Dave, email Judy, send a copy of the book to Steve, wait two weeks because it’s the holidays and the store is swamped, etc. Follow these guidelines. DON’T follow staff around the store pitching them your book, especially if they’re trying to help customers.

Read MoreOne of the most valuable methods of research for writing a novel can be the in-person interview. Experts in a particular field or people who have personally experienced something related to your story can not only answer questions put directly to them, they can provide experiential, sensory and other details it might be impossible to gain any other way.

When I talk to other writers about conducting interviews as part of their research, many express trepidation or outright intimidation at the prospect. This is understandable. First of all, many of us in this profession are introverts, and asking forthright, sometimes intimate questions of people we’ve just met falls outside of our comfort zone. Second, the people we seek to interview are often busy professionals, sometimes holding positions of high status. How can we approach them with any expectation of receiving their time, particularly if we’re unpublished, unknown writers?

The answer is to choose carefully the people you approach and to act professionally and with confidence–even if it’s an act at first. Don’t know where to start? No problem. Here is an 18-step process (yes, 18!) for interviewing people for your novel.

Read More

The first Writer Unboxed Un-Conference begins tomorrow! (Applause, shouts of joy, cheers, hugs, panicked rummaging through clothing when you realize you have nothing to wear.)

The Un-Con promises to be unlike other writing conferences. It focuses on the writing part of being writer—developing our craft, building our inner strength, and actually writing and telling stories. There will be networking, yes, but no pitching, no marketing lessons, no sliding copies of your manuscripts to agents under bathroom stall dividers. (Please, please, don’t do that.)

In other words, the Un-Con will be Un-Conventional. We’ll spend a week sharpening our literal and metaphoric pencils and deepening our writing skills. That might mean finally understanding a specific element like voice, or acquiring new writing-life skills, like strategies for how to write through difficult times. Or perhaps we’ll just soak up every word Donald Maass says, regardless of topic. No matter our approach, we should come away from Salem next weekend better writers than we are today—assuming we apply what we’ve learned.

But what if you can’t make it to the Un-Con in person? Don’t worry; you can Un-Con on your own. First, you can follow what’s happening at the conference in real time on Twitter by following the hashtag #WUUnCon throughout the week. Second, we’ll try to post recaps and materials from the conference here at Writer Unboxed later in the year.

Third, you don’t need to be at the Un-Con to shake up your writing practice and try something new. As the dark hours of the day grow longer and people retreat into their caves against the cold and the wind (at least that’s how it works where I live in northern New England), the timing is perfect to consider what new element you can introduce into your writing, or how you can experiment. How can you wake yourself up when the whole world—or at least the northern hemisphere—is about to curl into itself and go to sleep?

Read More