Posts by Tom Bentley

Photo by Gabriel Pompeo: https://www.pexels.com/photo/father-and-child-playing-with-a-pig-4676941/

We are industrious sentence-builders here at WU, but sometimes motivation fizzles, ardor fades, and a brave sentence’s beginning loses faith at its end. Never fear! In the spirited spirit of Mad Libs, we will build a story of stout sentences, broad-shouldered and charismatic.

Here’s the deal: I’ll list a number of story-building structures, and provide one sentence to light the fuse. You, not unattractively drooling in anticipation, will mentally write the next. And then I’ll reveal the “correct” sentence, since I am driving this careering sleigh. Not exactly democracy, but hey, we’re used to that by now. Unto the breach, dear friends:

Prologue

Kristy Silden watched, with a mixture of revulsion and fascination, the heavily lipsticked piglet dance in its stall.

She was fascinated that the pig had so precisely applied the lipstick, but revolted that the shade was so inappropriate for its pink spring skin.

Setting (Years Later)

The little farm, now hers, lay in a narrow valley, with the Saskatchewan mountain ranges looming on all sides.

She knew there were no mountains in Saskatchewan, but why fetter a wheeling imagination?

Foreshadowing

Ever since she’d seen Claudia, her beloved pig dancing those years ago, she’d wondered if that memory was a dream—and Claudia had aged with that memory.

But Claudia had always been there, and always would be—wouldn’t she?

Inciting Incident

Kristy watched Claudia in the pen, tottering on her once sturdy legs—could she really be that old?

Growing up together, Kristy thought of Claudia as a best friend, but most pigs only live to be 12 or so; Claudia was 11.

Call to Adventure

Kristy finished the Farm Finaglings article about the Berkeley scientists using CRISPR to edit a pig’s genes.

Kristy answered a ringing in her head: “This is Adventure calling; wanna go for a ride?”

Conflict

Kristy and Claudia argued about which vehicle was the best to get to Berkeley: The trusty ’52 Chevy truck her dad had left her (and which could carry a lot of slop), or the 2017 Prius hybrid.

They opted for the Prius, since Claudia couldn’t drive a stick; they could pick up slop at their stops.

Saving the Cat

The highway humming, Kristy idly wondered if a cat would have been a better companion than Claudia.

She made a mental note to start saving up for a cat.

Microtension

Kristy wrinkled her nose, and turned to Claudia, finding that Claudia had wrinkled her snout and turned to her.

They both burst into giggles, though Claudia’s were more of a snurfle.

Dilemma and Flashback

Saskatoon, Edmonton, down into the States to Montana—west to Seattle and south?

Quick diversion to Vegas instead—she’d won $35 on a nickel slot her dad let her play when she was fifteen, and the memory sung.

Man in a Hole

They had to creep slowly by a worker in a manhole in Reno.

Kristy thought he looked a lot like Ryan Reynolds, but Claudia just snorted.

Ordeal

Finally made it to the Berkeley lab, but Claudia was clearly slipping.

Kristy and Claudia’s eyes locked as the pig lie on the table; Kristy could see the faint trace of lipstick in Claudia’s last smile.

The Reward

The cloning was successful; through the sadness, a squealing little piglet was worth the month’s wait.

No Claudia to help drive home, no Claudia at all—but man, this Clara had more to say than talk radio.

The […]

Read MoreSome items I doodled at the bus stop. Well, not really

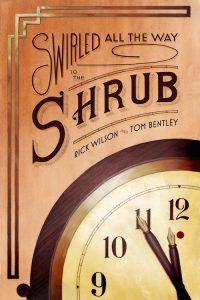

Many book covers do well with a pretty face. But sometimes you have to go with someone’s rear end—you’ll see what I mean in a minute.

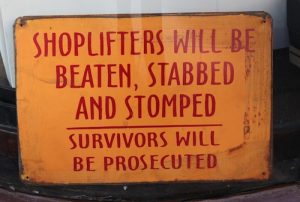

Through all my high school years, I was a lunatic thief, and became more and more brazen: I would dribble basketballs out of stores, march out holding new briefcases as if I were a businessman, stroll out with completely unrolled sleeping bags—my behavior was quite mad. I sold much of the loot at school.

I only stopped—temporarily—after spending a few days in jail for stealing a bottle of Scotch. Budgeting as a high school student can be so restrictive—stealing all the things I “needed” seemed to be a reasonable answer. Oh, I was an altar boy too—hmmm.

Clarity came to me on how I could pay my debt to society: I would write a memoir about my shoplifting business, in which I could complain about how all those stores and plainclothes people tried to thwart me. So I did. I finished the book a while back, checked it many times for the proper use of the semicolon, had a developmental edit and a copyedit, and then mulled over whether my stickman drawings of someone stuffing a tape player in their coat (collectors’ items, suitable for NFTs) would work for the cover. No.

Asking the Pros What They Know

So I checked out the sites of admired writers who are generous with their resources. I looked over Joanna Penn’s list of cover designers and Jane Friedman sent me her list of editors and designers. Jane’s list included Studiolo Secondari, for which I got a fortuitous second recommendation. I contacted Linda Secondari, head of the studio, and had a 30-minute Zoom call with her on my work and her process. She was grateful we were on Zoom, because I could tell she was nervous about me stealing the family tableware.

On request, I sent her 10 cover images I admired, taken in my local bookstore, with brief explanations of what I liked about the cover, whether it was image/illustration, typography, colors or something less tangible. That cover bundle is the lead image of the post here.

She then sent me a 4-page creative brief, a portion of which I’ve included below. The brief covers a number of points on cover possibilities and flavors, image potentials, and also had a number of questions for me. I replied to that brief with thoughts on her thoughts (we are thinkers!), answers and some questions of my own.

Juggle the Votes (Then Rig the Voting)

After a couple of emails, she sent me four cover comps based on our discussions, seen below.

Debriefing, that’s the criminal mastermind at 16 in the first shot, two modelings of the Stones’ “Sticky Fingers” album cover (with type somewhat modeling the Sex Pistols “Never Mind the Bollocks” cover) and the last perhaps a take on an SciFi/drug fantasy feel, though the colored disks there were to be later rendered as candies. But if they brought LSD to mind, that was part of my diet then too.

I circulated the comps to 25–30 people, not all of them […]

Read MoreWith apologies to Isaac Newton, who I’m sure had polished off a great deal of hard cider before being bonked by that apple pulled earthward, I’ll paraphrase his first law of motion: most fictional characters in their conventional orbits aren’t intriguing unless they are acted upon by an external force. And a fine way to force that force is to put them on the road, meeting people and places that tilt their gravity and pull their thoughts and actions a sharp tug from their safe routines.

Joseph Campbell’s oft-cited Hero’s Journey is likely the most circulated exposition of this notion, outlining a series of stages by which a person is compelled from their ordinary world into an adventure they first resist, then are mentored in preparation for the quest, meet allies and enemies, must overcome a supreme challenge, and get home in time to do laundry.

My first self-pubbed novel (which feels like a lifetime ago), All Roads Are Circles, pulls a dipstick from that tank, though considering my main character’s disposition, the Stooge’s Journey might be more apt. That book was loosely based on a 6-week period when I was 17 and hitchhiked from Vancouver to a small town in Ontario and back, a jaunt of fun, madness and peril.

To draw on: Drivers driving stolen cars, drivers who tell you that they are JUST coming on to their first hits of acid (and smiling at you in that special way as they accelerate to lunatic speed), drivers pulling out guns “just to show you that there won’t be any problems,” a van full of people ALL on acid, playing Blue Oyster Cult at ear-bleeding volume, and insisting, and I mean insisting, that you ride with them for HOURS, drivers who wept, cursed and wanted so much to share their tiny chewed rag of earthly experience expressed so succinctly … in seventy-seven chapters, blow-by-blow as you weakly nod.

It’s hard to forget the individually hitchhiking strangers in the back of a pickup on the return ride to Vancouver, who surrounded by other hitchhikers, had sex under a tarp. After they’d known each other for two hours.

The actual trip was fodder (sliced, diced and spiced) for many of the character-revealing escapades for the novel’s two protagonists, who have secrets from one another that vividly color their behavior. Those secrets are only revealed when they vie for the attentions of a worldly young woman—a wholly invented Circe not met on the real trip—they take up with on the road, leading to their collective Supreme Ordeal.

Clearly, writers can’t just fling characters all over a map and just hope fortune’s tumbleweeds scratch their shins in a reader-pleasing way. But picaresque adventures that don’t rely on a crutch of 1-2-3 episodic challenges can be satisfying stories of trial and growth. A few examples from novels I’ve read, some long ago, some fresh:

Books to Inspire Your Traveling Hooks

Think of Huck Finn and Jim rolling down the Mississippi, bumping into liars, cheats, stalwarts and good souls in a chain of fits and starts. The broader and more fulfilling story—despite the tangents of their fortunes—is the deepening connection between the two and […]

Read MoreAn editor waiting to eviscerate the nearest adverb

It is a truth universally acknowledged that the very best thing you could do for your writing is to tighten it up, just a little. Still with me?

With bowing and scraping apologies to Jane Austen, my take on that initial sentence that clogged your pores: it’s a gasbag, a dirigible without a destination. Why? Because it’s filled with unnecessary words and phrases. It’s filled with air, not substance. But this is air that doesn’t breathe life into your reader’s lungs—it suffocates them.

Consider: any sentence that has a qualification, a dodge, is a sentence that whimpers. Words like “very” and “really,” which seem to be intensifiers, are the opposite—they are diminishers. They are the celery left a year in the cellar: no snap. And a clause or phrase like “It’s a fact …” or “just a little” might seem to refine a sentence, give it some razoring of thoughtful gradation, but instead it hobbles it.

Really, Just Very Bad

Remove some of the fluff, and you get a working-class sentence: “The best thing you can do for your writing is tighten it.” But wield the scalpel again, and you get something crisp: “Tighten your writing.” That sentence, which turns a key in a lock, implies that the tightening will improve the understanding, rather than making it bloatedly explicit.

Of course, if you’re an essayist, a fiction writer, a vaunted creative, you might chafe at the constraints. There are times when sentences need luxuriant branching, elliptical orbits to trace their flight across the heavens. But even then, the “verys,” the “justs,” the “reallys,” the “it’s clear thats”—those blackguards rob your writing of vigor.

Vigor = good. Languor = bad.

All Modifiers Are Not Created Evil

Sometimes modifiers can add nuance to a sentence so their absence is loss, not gain. “He took a few, halting steps, expelled a gust of breath and took a voluptuous fall.” If there is intent behind your diction, your use of “halting” (and even “voluptuous” in this instance) could serve a narrative purpose. At least it’s arguable. But the actually here: “Actually, I couldn’t stand him” actually, factually, does nothing. Same with “quite” and “rather”—something that’s “quite exciting” fails to excite.

I am very guilty of veritable volumes of verys in my writing; for me, “just” is also just a spasmodic touch-type away. One of my favorite Mark Twain quotes is, “Substitute damn every time you’re inclined to write very; your editor will delete it and the writing will be just as it should be.” Verily.

Adverbs Under Editing Threat!

There’s been a threadbare-but-broad blanket of denunciation of adverbs and adjectives thrown over prose the last few years, but that’s employing a squinty eye blind to when modifiers can add color and spark to a page. All of those urchin adverbs and adjectives aren’t bad—just the ones that are padding, or those that substitute for strong verbs and nouns. Used with discretion, they are ketchup with fries. (Or sriracha, if you need more kick.)

Mechanical Brain Man Machine by aytuguluturk on Pixabay

After my long professional baseball career was over, and I wrapped up teaching undergrad literary theory at Harvard to Steven King and Margaret Atwood (and took a quick detour to consult on lab work in first developing Messenger RNA), I thought I’d settle into a life of leisurely reading of the classics, a stout glass of port in the early evenings, and the trills and cheeps of friendly birds at the water garden.

And then I woke up. And I thought, “Man, doesn’t anybody dust around here?”

My version of reality, which likely shares at least a few of the touchstones that yours does, has never felt as shaky as it has in recent days, making me wonder if I basically had it wrong all along. My latest “Ugh, what’s that smell?” came after reading the developmental assessment of a memoir I wrote over the first seven months or so of the pandemic. The book centers on my high school shoplifting business, covering years of thefts and sales, theft techniques and multiple brushes (well, make that handcuffings) with the law, and my eventual coming to my senses—or a semblance of sense.

I did months of pitching in the late fall and winter, which has resulted, after some mild interest, in 65 rejections, half directly saying “no,” and half those agents or publishers not responding at all. Thus I sought the help of a developmental/assessment editor.

The editor did a sound, credible job, many times buoying me up with praise for passages and turns of phrase. But she pointed out many diversions from the theme, which I thought was “Catholic boy in the suburbs breaks bad but finally forms a conscience.” She pointed out that a reader might see multiple themes, or what I presumed the main one expressed murkily. She also noted many attempts at wit that clunked, many changes in tone that didn’t produce music. And she was right.

I wasn’t surprised, just disappointed in myself. I thought that a lot of the things that she dubbed as diversions were part of my building a psychological profile of that kid with the happy hands, and what might have caused him to go that criminal way. (I took a psychology class in junior college, so I know all about this mind stuff.) And having been both an editor and on the receiving end of edits since somewhere around Gutenberg’s time, I should have been able to take it stoically.

The Stoics (who seem to be having a renaissance, so keep those skinny jeans) have opined in several ways that there is the event and separately, how we react to the event. As Seneca, one of the heavyweights said, “Reason shows us there is nothing either good or bad but thinking makes it so.” But when I read the well-reasoned (and warm) remarks from my editor, my initial reaction was, “God, she hated it!”

But that wasn’t true, no. Not at all.

Read MoreRemember when you were in high school and you told your mom you were going to Susie Straightlace’s house to study but you really went to Rachel Riskwhisker’s rager where you drank so much Grape Crush and vodka you had to crawl home with one eye shut and you peeked in your living room window to see if your mom was still up and you saw that she had removed her glowing, rutabaga-shaped brain from its cranial case and was recharging it with what you had once thought was a giant electric razor and you realized that she was an alien overlord?

I don’t, because that’s your memory, not mine. But gollyjeepers, I’ve got some doozies. (To be clear though, my mom was an angel.) Me, I had a tidy little enterprise in my high school years and beyond: professional shoplifter. I say “professional” because I ascended the ladder of five-finger skills through enterprise and gall, and because I sold the goods I lifted to high school acquaintances. Satan whispered in my ear a lot those days.

Well, I sold some of the goods–the significant amounts of liquor I stole were consumed by me and my cronies. Many of those were quaffed in the name of science, since items like blueberry schnapps and MD (Mad Dog) 20-20 “wine” weren’t actually meant to be ingested—by humans at least. And I was the guy who did steal Abbie Hoffman’s Steal This Book when it came out—Abbie, you asked for it.

Confessional memoirs have possibly peaked in popularity, but I’m always late to the party, so I recently wrote one. I have written essays over time about the impossibly poor judgment I had as a lad, but I hadn’t thought about writing a memoir until I was editing one for a client, hers being a 140,000-word composition about her years as a marketing executive in the senior care industry.

Part cautionary tale, part horror story about the dark side of aging, part song of friendship, part instructional on best and more humane industry practices, hers is a funny, sad, sharp and scary volume. Working with her on it made me realize that I could shape my misdeeds into a book, and at the least, terrify the parents of high schoolers who think their charges are studying at Susie’s.

Read MoreThe guy with the scythes is happy—he’s still got a job

“We experience pain and difficulty as failure instead of saying … literature has come out of it.”

—Marilynne Robinson

Trigger warning: several bummers ahead. Yes, your groaning is my groaning, and though this post will dig some dark coal, there is a writing diamond or two herein as well. And before we mention that effing virus, a little rehash:

Six months ago, my cat Malibu disappeared. I was deeply bonded to her, time and again laughed at her antics, worried when she was sick, looked to her regularly for comfort and companionship. Though I know she’s not coming back, I still scan for her striped shape in the nearby fields.

A few days ago I saw her sleeping on our bed—but it was just a crumpled-up shirt. She was semi-feral when we got her, so we continued to let her roam outdoors in the daytime. That felt right, but now I feel I failed her, that I failed to protect her. I still see her, purring with eyes shut in my lap. Six months later, the loss is daily.

Loss is a hollow place.

We try to help where we can, and try to survive our own trials and stresses, illnesses and elections. We work really hard at not being driven crazy by noise and speed and extremely annoying people, whose names we are too polite to mention. We try not to be tripped up by major global sadness, difficulties in our families or the death of old pets …

—Anne Lamott, Stitches

Two days before Christmas, my old boss skied into a tree at Tahoe and died. Though I hadn’t worked for him for years, I had always admired his goofy gusto, and how he drew others into his mad enthusiasm for skiing, diving, boating, hiking. At his memorial a month or so ago, many people testified to his fundamental decency.

On a cliffside above the beach, surrounded by the large memorial crowd, his son, a professional dancer, improvised to acoustic music a hard-twisting, and soft-flowing, and fully mesmerizing dance, a tribute to his father. Those movements were so knifing and experiential I can’t accurately describe their immediacy, but the dance made me burst into tears.

“They understood that the meaning of life is connected inextricably, to the meaning of death; that mourning is a romance in reverse, and if you love, you grieve and there are no exceptions–only those who do it well and those who don’t.”

—Thomas Lynch, The Depositions

Photo credit: alittleblackegg on Visualhunt.com / CC BY-NC-SA

When I was 11, frustrated and sugar-crazed, I tried to open a Coke can with a steak knife. I’d broken the can’s pull-tab ring and shrewdly thought that I could plunge the knife through the aluminum seal. Instead, I plunged it fully through that flying-squirrel skin web between my thumb and forefinger. To this day, I can rub the little ball of scar tissue on that skin, and reflect on flawed decision-making.

In my mid-twenties, I was going to heat up a tortilla on an iron skillet. Having heated up many a tortilla on many a skillet, I knew that I could just hover my hand over the skillet to see how hot it was. Instead I put my hand flat on the surface of the pan. Message received!

But not quite, because years later, I did THE VERY SAME THING. Message not learned. (My book, Cooking with Tom—or Cooking Tom, available now.)

This is not to emphasize that I’m an idiot (though one could argue), but that people often do things that we puzzle over. Arming your fictional characters with specific eccentricities or traits—hates cats, never turns left unless forced to, starts a book by reading the last page—is a way to anchor a reader to a character, whether by delight or confusion or revulsion.

Saabs or Die

In A Man Called Ove, noted curmudgeon Ove loves Saabs. Other cars are for fools. “In the parking area, Ove sees that imbecile Anders backing his Audi out of his garage. It has those new, wave-shaped headlights, Ove notes, presumably designed so that no one at night will be able to avoid the insight that here comes a car driven by an utter shit.”

Now, Ove is always a sourpuss, but when this particular trope on the irrevocable superiority of Saabs recurs, you get a little tingle, “That Ove, what a freak!” that puts him deeper into your skin. You begin to look forward to him railing about other people’s cars.

In A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court, Twain’s man-out-of-time lead character (“The Boss”) does a lot of work in the book to undermine (and make fun of) feudalism, the monarchy, and undemocratic elements of medieval England. But The Boss is never pure: he introduces modern marketing to the era, doing things like putting advertisements for soap on itinerant knights’ shields and introducing fee-based telephone service. The Boss’s commercial efforts, which are returned to over and over, is a side-plot that has the reader wondering what he’ll try to sell next.

And that bag o’ quirks can sell the reader on the character.

In Celeste Ng’s Little Fires Everywhere, Izzy, one of four daughters of the central character, is a black sheep of sorts. She is stubborn, opinionated, sometimes righteous, often clashing with her mother and other family members. What might first come off as a whining punk turns more into hard-won spunk when you see her bristling traits recur in new circumstance. There’s an “Oh jeez, who is she going to offend next?” kind of feeling, but when it happens again, you both react to it and further anticipate it. Read More

Book covers are influential. When I saw Abbie Hoffman’s Steal This Book in the store, I stole it immediately. (Abbie, thank you for not titling your book Eat Your Poop.) I’ve been motivated and moved by cover artistry many times, so much so I’ve paid for books about which I knew little other than their cover’s invitation.

There are seemingly endless combinations of illustration, typography, geometry and color that simply click that “yes!” in our heads—the cover is something felt, it paints an inviting dimensional landscape in our imaginations.

And then there are covers that are like eating poop.

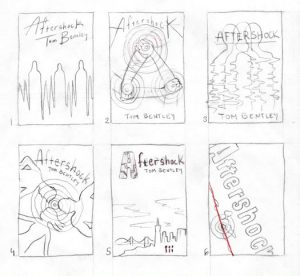

When I slapped awake an old novel that had been Rip Van Winkling in my mind’s grotto, and decided I might self-pub it, I concluded my ability to draw only stick men—stick women, out of the question—was a stopping point. So I engaged the services of Alicia Neal, a woman who had illustrated the cover for a spectacularly unpublished collaborative novel of mine. She had done compelling work on that, so we began the email dance of grubby, obscurantist author and genial, accommodating designer to come up with an expressive, irresistible cover. (I gravitated toward Steal This Book as the title, but worried about copyright.)

After confirming that she’d like to work on the design and setting up a tentative timeline, I sent her the query, synopsis and first fifty pages of my novel, Aftershock. Those pages introduce the reader to the three main characters of the work, who are unceremoniously tossed together by the 1989 San Francisco earthquake. The landing after the tossing doesn’t go well, but that’s fiction for you.

So, what follows is a condensed—and it’s still way long for a standard WU post—exchange of our emails and the images of the developing cover, which evolved from rough sketches to a lovely thing. If this whole piece is tl;dr, just breeze through the images while sipping from an umbrella drink.

After reading the novel’s beginning, here’s what Alicia wrote back:

I read through everything you sent me. I thoroughly enjoyed the first 50 pages, and I’ve been working on concepts all weekend but I have to admit I’m a bit rusty, the visual inspiration hasn’t quite hit me yet. I’m leaning toward something that plays on the theme of the earthquake: a destructive force, uniting the paths of three very different people (unity through division, or order from chaos, etc.). I’m still working on getting you thumbnail sketches in the next couple days, but when you have the time to take some photos in the bookstore like you mentioned, that would be a huge help.

Here’s some of my response (which is embarrassingly vague), to try and kick off the process:

I guess a stereotypical image might have the Golden Gate Bridge in it, though it was the Bay Bridge that was damaged by the quake, though bridge damage doesn’t figure greatly in the story. Downtown San Francisco does.

I didn’t have any great starting ideas, other than maybe having the “A” in the Aftershock title be cracked as though it were from earthquake damage. But that might not be that original either. Anyway, I’ll try to get some covers for you a bit later in the week and try to think of any […]

Some light years ago, I was living with my best friend in a small apartment in Southern California, on my own for the first time. It was our first New Year’s Eve together as that eager, barely tolerable species: raffish apartment-dweller-type dudes, barely out of high school. We were going to celebrate that self-congratulatory state of being with a New Year’s party.

That evening we had a respectable turnout of our friends, acquaintances, and other welfare cheats of note, and had settled in to the numerous foolishnesses of New Year’s Eve. We had a wee dram, and a wee dram more. As it neared midnight, my housemate and I had an insight: to christen the New Year, we could both doff our clothes and walk around outside in the soft warm rain that was falling. Did I mention we’d had a drink or two?

Equally inspired, my girlfriend decided to join us. We goofed around a bit out front, and then we saw two figures approaching up the block. In the great spirit of improvisation, my housemate and I worked up a plan: we would walk up to the people, acting as though we were in our fully clothed at-ease, and wish them Happy New Year’s. The creative act, in action.

Remember, it was dark and misting outside. Thus you can understand that it wasn’t until we were but five feet away from our prey and about to spring our greeting when we realized it was OUR LANDLORD AND LANDLADY, who lived only a few blocks away, and who had decided to walk over and wish us happy New Year’s. The fact that they were straight-laced, reserved people, and Eastern Europeans yet, made our calculation all the less calculating.

Well. We had perfect presence of mind and body: Run! Without saying a word, we turned and bolted for the house. Somebody at the party caught a classic snapshot of my housemate in manic mother-naked retreat into the house, eyes bulging out of his head like boiled eggs. Perhaps we thought we’d be safe inside. I literally ran into my closet and hid, lacking the benefit of clothing. I did say that I was young, right?

Read MoreMalibu, humble-bragging: “Pretty, oh, I’m not THAT pretty.”

I’m editing a biography of an accomplished pediatric heart surgeon. The author had interview access to many of the parents of the children with damaged hearts, and he was also allowed to be in the operating room when sometimes superhuman attempts were made to repair that damage. What struck me (and terrified me too) was how with a factual narrative accounting of the bleak medical outlook for these tiny patients and the sophisticated efforts to save them, the book and its stories relentlessly pulled me into its emotional center.

I don’t have any children, so it wasn’t a reflex empathetic response. I think it was the unvarnished way the writing described the terrible conditions of these kids, born with severe defects in their hearts, and of the waves of terror and tedium that followed for the parents in attending to their care. Or helpless in the face of it. And then, in the operating room, a day of reckoning.

Vulnerability is the story’s core: here were children as young as three weeks old getting open-heart surgery, children as young as four years old getting heart transplants. The vulnerability of these tiny kids, the vulnerability of their parents—it was breathtaking. That emotional magnet in the writing pulled and pulled, no matter that some of the material was also technical and dry.

Read MoreIn high school, I had a close-knit group of friends, many of whom remain good friends today. Except for one, a person with whom I was remarkably tight for an intense period, and then it all fell away. (Let’s call him X, because X is a fine name for something buried, though “treasure” doesn’t come to mind.) X probably had the most ranging intelligence of all my friends, the quickest wit and certainly the most ingenuity: he was the kind of a guy who would look at a dead radio, and in five minutes solder a spoon into its wiring and make its silence sing again.

But for all his charisma—and he had that—my friend had a sharp edge to him that impelled him to practical jokes, many of which seemed less than funny. He would put raw eggs in our beds that later made for soggy sleeping, soap our toothbrushes, surreptitiously tie some of our shoes together when in a group so when we got up we would stumble. He drove his Volkswagen van around a big tree in my tight backyard at mad speeds with my parents home and watching, so that it seemed like a demon’s visitation—what was that? He once dumped a full bowl of cereal and milk on me while I was sleeping, for no reason other than the feeling moved him. Because he worked in a pizza parlor, now and then he’d drive by, get out and throw entire pizzas on our roofs.

The moment that turned the corner for me was when he tied a string to our front door so that the bag of charcoal briquets that he’d tossed on the roof above would fall on one of us when the door was opened. The fact that it came down on my mother was the catalyst for what followed. All of my friends, my brother included, had some kind of grudge against him. “Remember when X spit in your drink and waited for you to swallow some before he told you?” “Yeah!”

We all had the stories. So we decided to humiliate him.

The Ambush

A couple of our group (also X’s victims) dropped out, leaving me, my brother, and two other friends, all of whom had suffered at X’s hands. Because all of them also worked part-time in that neighborhood pizza parlor (excepting me—I understood from an early age that work was unhealthy), they knew the routine: whoever was the assistant pizza “chef” would need, maybe an hour into the shift, to go to the refrigerated, locked storage shed out in the alley that flanked the shop, in order to bring in one of the five-gallon buckets of shredded cheese. We knew X’s work schedule, and we knew he would come out. We were waiting.

We were hidden in various places in the alley: behind dumpsters and the projecting side of a building. We had a dozen raw eggs and 10 water balloons. I was on top of the shed, hunching in silence, with two plastic buckets of tomato sauce. When he came out, we unleashed a fusillade of high-school-boys-mad-as-hornets hell on him, while howling imprecations.

Our work was effective. He was a miserable […]

Read MoreMy cat killed a hummingbird a few days ago. She brought it in, as cats will do, proud, thrilled with the hunt, mad with animality. If you have a cat that goes outdoors, you know the behavior: your pet’s standard personality is turned up ten notches to a twitching, eyes-afire clench of sinew and nerves.

In my cat’s case, she’s a poor birder, for which I give thanks. In years, I’ve only found evidence of one slain bird in our yard. She’s pleased to display the occasional vole or even a rat from the nearby fields, but I, the moral relativist, shrug off those captures with bland disgust.

But here, a hummingbird. A creature of darting beauty, an expression of brimming vitality in its pulsing flights. Hummingbirds are like a sudden flare in the darkness, the wow of light, the delicate lick of the flitting flame. But this one, its flame out, being flipped maniacally into the air and onto the carpet in surges by my cat, until I was able to grab it off the floor before another flick of the cruel claw.

And when I picked it up, the bird’s limp neck flashed the ruby iridescence that contrasted with its green/gold feathers—beautiful yet, but just a shiny death mask. I put the bird out in the nearby fields, and then felt a pang of shame.

This post isn’t designed to be a forum on the politics of allowing a high-level predator like a cat to roam outdoors. My cat, Malibu, was a semi-feral cat that we’d seen roaming the neighborhood for more than a year before we adopted her. As we later found out, she had survived on the kindness of strangers—and of course, on her hunting skills. What is more interesting to me now, as a writer, is the shame. Since Malibu isn’t, as we are, gifted and cursed with a sense of self-consciousness, I had to experience shame in her stead.

Shame and Guilt, Kissing Cousins

Shame—and its first cousin, guilt—are useful tools for writers (and such intrigues for psychoanalysts): instances where a character was shamed, or felt deep guilt are often motivational markers for later character behaviors. We get a fine sense of the power of shame in our early stories: when Adam and Eve eat the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge, the sudden sense of their own nakedness sweeps over them in waves of shame.

[Note: I don’t know about you, but I would have made a fruit salad out of those apples long before that wiggly fellow in the grass waggled his forked tongue at fair Eve. And I’m all in favor of some people being naked, but clothes do make the man.]

Guilt follows in scene two, when God questions why they bit into the forbidden. Not having good lawyers, each bobs and weaves for blame; expulsion from the Garden follows. (And their boy Cain had a lot of splainin’ to do later for his own guilt-laden crime.) That shame/guilt of our forbears, a backstory bear trap, became a lurking presence in many books, Biblical and not, to come.

Read More