Posts by Sophie Masson

In a previous post, I wrote about the ‘red lines’ that authors and publishers alike might encounter in book contract negotiations. In this post, which like the earlier one is drawn from a conference paper I presented late last year, I look at another important question for authors: Are big or small publishers easier to deal with when it comes to contract negotiations?

In my home country of Australia, the size and importance of the small and independent press sector has grown exponentially in recent years, which means that more authors and agents are working with small presses than ever before. In the paper, I presented interviews with authors and agents who had worked with both big and small publishers, focusing on how they viewed the contract negotiation experience. The answers offer some illuminating insights on the contrasting experiences and opinions within the industry:

‘Most publishers have a take it or leave it attitude to contracts. The bigger the organisation, the more they exert their will in terms of the details within the contract.’ (author-illustrator)

‘Small publishers are generally more nimble and flexible and are often less intent on holding certain rights so we’re generally able to reserve more for the author. Having said that, there are some small publishers who are inflexible on their terms because of their business model and that can be off putting for creators and/or agents.’ (agent)

‘I have found there has been more room to move in contract negotiations with larger publishers than small. The smaller the publisher, the more limited the budget, the less room there is to move with regards to money. But I have negotiated things like future writing work clauses, division of rights, and the number of copies I get.’ (author)

‘It’s not size but the company. For instance, taking two of our biggest publishers – one is very difficult to negotiate with and has a very hard-line approach, which is actually a disincentive to pitch to them at all, and another is always fair and reasonable to negotiate with – not a pushover, but you know you’ll get a straight answer. Many smaller publishers are great to negotiate with – they know their business and where they can bend, but a few use their small size to (wrongly) try to justify very poor terms for authors indeed.’ (agent)

Read MoreYour book is coming out soon and you want to mark its entry into the world. You don’t want it to just slide out unnoticed amongst the serried ranks of ‘New Releases’ in the bookshops. You want it properly launched. But your publisher isn’t keen to do a launch. Too much time and effort for too little return, they imply. Unless you’re a celebrity, or a highly publicized first-time author with a dedicated, free-spending, large family and friends network, book launches aren’t a big part of many publishers’ promotional strategy these days. But—surprise, surprise—we authors still love them! And so it’s become more and more common for authors to put together their own book launch.

But launches are not as easy as they might sound to someone who is new to the process—that time and effort cited by reluctant publishers as reasons not to have one are very real things. As a veteran of many launches—both those I’ve attended and those I organized for my own books as an author–I can vouch for that! I’ve also recently organized other people’s book launches as a small-press publisher–generally small publishers are warmer to the idea of book launches than big ones. So I’ve accumulated some knowledge of what can help to make your launch a hit and not a miss!

First of all, it’s about planning. Planning well ahead of time, months ahead of time. Ask yourself:

What kind of launch do I want? Big, small, straightforward, themed–that is, not just themed around your book, but with a certain look? You will not be surprised to learn that a big, themed launch is the most time-consuming and expensive to pull off. However, don’t let it stop you if that’s what you want. With our small press, we’ve run a couple of themed kids’ Christmas book launches with a cast of thousands. Well, not exactly thousands but you know what I mean. Readings, music, party gifts and prizes have worked really well, but have also been a large amount of work to get right, with many panicky pre-launch moments.

The smaller, more straightforward launch, where someone launches the book with a short speech, the author says a few words, then everyone toasts the book baby with the sparkling stuff before hopefully lining up to buy signed books whilst trying to graze on the last remaining nibbles, might not be as glamorous but they can still work really well, especially if this is your first book, you’re celebrating it locally amongst your family and friends, and everyone’s excited to see you in print. When you’ve had several books out, it’s better to space out your launches—don’t have one for each book, because people, even your nearest and dearest, get launch fatigue. And small, standard launches are much, much easier to get right, aren’t nearly as much work, and booksellers know exactly what to expect and don’t get jumpy about unusual activities happening too close to those neat shelves.

Read MorePublishing contract

Recently, I presented a research paper at a publishing conference which was themed around the experience of negotiating, and signing, book contracts. The paper, based on a series of interviews with Australian-based authors, publishers and agents, looked at all kinds of questions around book contracts. One of the questions which aroused a lot of interest was the idea of the contract ‘red line’—when do you know, whatever side of the publishing table you’re on, that you need to walk away? I thought WU readers might be interested to read some of the things people said.

General comments:

All publishers and all creators are different, but they all need to be able to communicate clearly with each other. If a creator is uncomfortable with discussion at the contract stage, this is a good time to consider whether there is a good fit with the publisher (publisher).

The time to walk away is when an author or publisher comes to believe they won’t be able to sustain a positive relationship any longer, because if you can work together and communicate effectively then there may still be a way forward, regardless of the written contract (author).

I think you should walk away if you feel unduly pressured into making decisions that you are not comfortable with. Perhaps another publishing house may suit you (publisher).

If the publisher won’t negotiate on something important to you, don’t sign. Once you sign the contract you’re bound by it, no matter how unfair it is. Authors have more options than ever before to get published, so just walk away (author).

What about specific ‘red lines’? These ranged from:

Read MoreAuthors have used pseudonyms, or pen-names, since the beginning of well, authorship. It’s fairly likely ‘Homer’ wasn’t the real name of the poet who wrote the Odyssey and the Iliad—but nobody knows for sure! Famous authors as varied as Mary Anne Evans (George Sand), Eric Blair (George Orwell), Theodore Geisel (Dr Seuss), David Cornwell (John le Carre) and JK Rowling (Robert Galbraith) have all adopted pen-names, for various reasons. But it’s not just the famous and exalted who adopt pen-names; many of us writers have used pseudonyms at one time or another. I myself have used two—Isabelle Merlin and Jenna Austen. Each pen-name was used for very particular kinds of books: the Isabelle one for a quartet of YA romantic thrillers set in France (published between 2008—2010) the Jenna one for a duo of middle-grade/tween romantic comedies, the Romance Diaries, inspired by Jane Austen novels (both published in 2013). Each worked well within its genre, despite the fact no-one knew I was Isabelle, and it stayed that way for at least the third book, when my publisher revealed it was me; whereas neither I nor my publisher ever hid the fact I was Jenna. And nobody seemed to mind either way, though people who knew my writing under my own name were, surprisingly but gratifyingly, generally very surprised to discover Isabelle was me, as they felt the style was so different. Jenna’s style was different too, but because everyone knew it was me from the start, they adjusted to it quicker than they did than to the Isabelle style—because that name, and the enigmatic biography (which was all true, by the way, just not precise!) and ‘glamorous’ author pic (see above–and yes, it’s really me!) gave them a different experience, in keeping with the tone of the books. At least that’s my theory.

Anyway, I enjoyed the experience both times but went happily back to using my own name for my later books. But recently I started thinking about the whole question again, after reading an interesting post on a blog which argued that in the digital age it’s a silly idea to use a pen-name, especially more than one pen-name, as in these days of social media saturation you are likely to be found out, and people would be annoyed with you for tricking them. Besides, the author went on, there was much more understanding these days that writers can flit between genres, and so that reason for adopting the pen-name is no longer valid. So, was that right? Have we really gone past the time when pen-names are useful—are they more of a hindrance these days?

I don’t think so. Why not?

Read MoreFlickr Creative Commons: Thad Zajowicz

These days there are so many ways of promoting a book—yet also so many chances of that book not being noticed at all in the flood of promotion that washes over people daily. So as an author, what do you do? In this post I’m listing a few things that have worked—and not worked—for me. These are very personal observations of course; you may have had a totally different experience.

What’s hot:

Cover reveals on social media—accompanied by an intriguing ‘tag.’ These can start a buzz well before publication.

What’s not:

Book trailers on You Tube or similar channels. Heaps of fun to make but in terms of effects on sales, pretty much nil. You don’t get half as many people looking at them, compared to cover reveals. However, as long as they don’t cost you heaps of money and time to make, there’s no reason to not do it as it can be a nice adjunct.

What’s hot:

Interviews with local radio stations—a brilliant promotion, in my experience, although that may be because at our local radio station there are at least two presenters interested in books and publishing. They and their producers are very keen on local publishing/literary news stories. I have had many people over the years say they went to their local bookshop to find a book I’d spoken about on radio. If you have a similarly engaged presenter on local radio, cultivate them; it’s really worth it.

And by the way in my experience local TV can be good but is hard to get on board.

Read MoreThe hands have it: giving the poetry workshop

Recently I’ve had quite a bit of success with having poetry published for kids, in both magazines and book-based anthologies, with the most recent being the inclusion of no less than seven of my poems in the gorgeous anthology, A Boat of Stars (edited by Margaret Connolly and Natalie Jane Prior, published by ABC Books, Harper Collins Australia 2018). That’s generated quite a bit of demand for me to give poetry workshops, both for kids and adults. For one such workshop, which was for an audience of speech and drama teachers, I came up with a new concept which I’ve called Page to Voice, Pen to Performance and which focuses on the oral and dramatic aspects of improvised poetry in a simple, engaging and accessible way. I thought other people might be interested in the concept–and I’m very happy for anyone to freely use it in their own workshops, just with due acknowledgement of the originator, ie me. :-)

Here’s how it works: You choose a theme to build a poetic concept around first. In the case of the workshop I gave, I chose to build that poetic concept around something we know well and use in both performance and speech: our bodies, and specifically, five parts of the body: feet, hands, mouth, eyes, ears.

Then I used three different frameworks to use that concept with: body as music; body as metaphor; and body as mini-drama, to create three simple poems which are designed to be spoken and performed, but which also work on the page. The point, too, is they are improvisational: You shouldn’t think about them much at all, they are ‘instant poems;’ I made these up in just a few minutes.

So here goes:

Read MoreSo–the publisher or agent you’ve written to has responded favorably to your query letter, and now asks to see a book proposal. Attention spans aren’t long at the submissions coalface and if you miss your moment, it may not come again. It’s important that your proposal is not only ready to go, but leaves a positive impression. Whether you are writing fiction or non-fiction, the aim of the book proposal is the same: to convince your first readers of the credibility, value, and marketability of your book. Publishing is a collaborative business: decisions made at acquisition meetings are group decisions, and include not only editorial staff, but marketing, publicity, finance, and accounting, as well as specialist departments such as rights, educational, etc. The editor might love your proposal but she has to convince everyone else of its merits, so you need to help that process along by including the ‘meat’ of your proposal, i.e. a summary of the content of your book, plus either a story arc and character description (for fiction) or a list of chapters which indicate clearly what is in each one (for non-fiction). You also need to show you understand the market you are writing for. When you propose a book outside of your normal genre—say, like me, a fiction writer proposing a non-fiction project—this is especially important. It can be embedded within the body of the summary of the project, as well as flagged at the end. For instance when I was pitching my non-fiction book, The Adaptable Author: Coping with Change in the Digital Age, (Keesing Press, 2014) here’s how my book proposal summary began:

Getting published is every aspiring author’s dream, the focus of enormous energy, hopes and fears. The statistics quoted in articles and books on the subject can be dispiriting, so if that dream comes true, then as a newly-anointed published author, you can feel as though all your struggles are now over and you can relax into the life of the professional author. But getting published is only the start, and in retrospect, it can seem a good deal simpler than what follows: staying published, and maintaining a career as a professional author. That’s never been easy, but in a modern publishing industry in the middle of rapid and turbulent transformation, it has become even more difficult.

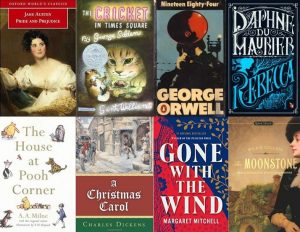

Read MoreIn my last Writer Unboxed post, I wrote about great first lines in fiction. Today I want to jump forward to the opposite end of a novel, and great last lines.

Last lines are important not only because they are the final words a reader will see in a book, but because they help to fix it in the reader’s mind. Great last lines can have the effect of sending chills down your spine, or making you breathe a sigh of satisfaction, or intriguing you with possibilities to come. They may make you want to go right back to the beginning to start again on what has been an exciting journey. Or they may simply make you feel pleasure at the thought you have been so skilfully guided by the author through that journey. Great last lines work because whatever feeling they evoke in you, they are both suited to the particular kind of story they’ve been telling, and they’re memorable. And generally short, like those effective first lines I mentioned in my previous post–though that isn’t always the case, especially with 19th century novels. Finally, they come in two main types: the kind that closes the story off completely, having tied up all loose ends; and the type that whilst not being completely open-ended, leaves the story door slightly ajar, as it were, allowing for the reader to continue wondering about the characters and their futures. I’m not talking about books that have sequels here—those obviously will have last lines that are open-ended in one way or the other—but standalone novels.

Let’s look at some favourite examples of both types of last lines, and why they work.

First, the ‘closed’ kind:

He loved Big Brother. (from Nineteen Eighty Four)

We know from this chilling last line of George Orwell’s famous dystopian novel that nothing will be right for Winston, the main character, ever again; his spirit has been utterly broken.

And so, as Tiny Tim observed, God bless us, every one! (from A Christmas Carol)

In contrast, this line expresses joy that everything worked out for everyone, the perfect ending to Charles Dickens’ short novel that blends ghost, fairy tale and morality tale elements.

Darcy, as well as Elizabeth, really loved them; and they were both ever sensible of the warmest gratitude towards the persons who, by bringing her into Derbyshire, had been the means of uniting them. (from Pride and Prejudice)

This last line from Jane Austen’s celebrated novel underlines both the happiness of Darcy and Elizabeth and their thoughtfulness regarding other people. You know they are set for a good future!

But wherever they go, and whatever happens to them on the way, in that enchanted place on the top of the Forest a little boy and his Bear will always be playing. (from The House at Pooh Corner)

With this nostalgically beautiful line, AA Milne both points to the end of childhood and the putting away of favourite toys: yet the enduring power of memory and imagination.

There are many more examples, of course, that we could find—but now let’s look at the ‘slightly ajar’ kind:

Read MoreIn the first month of a new year I thought it was fitting to write a post about first lines. First lines are important because they create an immediate impression in the mind of the reader. If they’re memorable, they can pass into common cultural reference. Think for example of the famous opening lines of Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice, or Charles Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities, which apparently are the most widely-known, according to this Guardian article. But ‘the past is a foreign country; they do things differently there’, from LP Hartley’s The Go Between, and ‘happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way’, from Leo Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina, are also common cultural currency, quoted again and again and sometimes in contexts far removed from their original source!

Here are some of my favourite first lines from famous books:

Mr. and Mrs. Dursley, of number four, Privet Drive, were proud to say that they were perfectly normal, thank you very much. (JK Rowling, Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s/Sorcerer’s Stone)

In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit. (JRR Tolkien, The Hobbit)

Last night I dreamt I went to Manderley again. (Daphne du Maurier, Rebecca)

It was a bright cold day in April, and the clocks were striking thirteen. (George Orwell, Nineteen Eighty Four)

Alice was beginning to get very tired of sitting by her sister on the riverbank, and of having nothing to do: once or twice she had peeped into the book her sister was reading, but it had no pictures or conversations in it, ‘and what is the use of a book’, thought Alice, ‘without pictures or conversation?'(Lewis Carroll, Alice in Wonderland)

Marley was dead, to begin with. There is no doubt whatever about that. (Charles Dickens, A Christmas Carol)

‘Christmas won’t be Christmas without any presents,’ grumbled Jo, lying on the rug. (Louisa May Alcott, Little Women)

All children, except one, grow up. (JM Barrie, Peter Pan and Wendy)

I could go on 😊 of course but I won’t! What I want to focus on is why those lines work so well.

Read MoreAt my grandmother’s.

I was born into a family where stories were all-important. Not just stories you read in books, though those were much loved; not just stories about imaginary people and magical lands, though we adored those; but also the stories that had made us who we were—stories of the family. As a very young child, I lived with my grandmother in France while my parents were away working in Indonesia, and she told stories of her past. Later, living with my parents in Australia, I heard many stories of their pasts, and the family pasts stretching well beyond them, into the mists of the centuries: in my father’s case, right back into the sixteenth century. Secrets and dramas, tragedy and comedy, big characters and twisty plots: they all featured in the family stories and we could never get enough of them. Later still, I told stories of my own past to my children, as well as passing on the stories from my parents and grandparents and way back. It was a natural thing to do, and it still is. And what I realised was this: the fact that I was brought up in that ferment of family story not only grounded me in my identity, it also had the effect of heightening my own memories of childhood and adolescence so that later, as a writer for children, I had a deep and authentic well to draw from, for my fiction.

But fiction’s one thing. Memoir is quite another. And writing stories about yourself and your family, for public consumption, is also quite different from telling them within the family. There’s so many things you don’t need to explain within the family, but for strangers to understand, to enter into the very personal world you are recreating, you need to at least set the scene. Memoir is written usually in subjective first person; but you need the third-person objective eye, too, if it is to communicate to readers and succeed as a work of art.

Read MoreEach year, in both adult and children’s fiction, tens of thousands of new books come out, and to keep up would tax the powers of even the most voracious reader. So why should we bother with the classics, books that first saw the light of day decades or even centuries ago?

My own answer to that question goes back into my childhood. Our house was full of books, many of them classics beloved of my French parents—books by authors like Alexandre Dumas, Victor Hugo, Jules Verne, the Countess de Segur and others. We children didn’t think of them as ‘classics’; the ones that we loved (not all of them, of course) we just thought of as great stories. As well, thanks to our great local public library, I discovered many fabulous English-language children’s classics that my parents, having grown up in France, didn’t know: Alice in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass, The Railway Children and Black Beauty; The Princess and the Goblin, Wind in the Willows, The Jungle Book, Winnie the Pooh, The Secret Garden and The Little Princess, The Wizard of Oz and the Narnia books, The Silver Skates and The Silver Sword, Little Women and What Katy Did at School, Pollyanna and Anne of Green Gables. And many, many more!

Later, in high school, thanks to wonderful, dedicated English teachers, I discovered lots of other classic books, novels and poetry: works by Charles Dickens, Shakespeare, William Blake, WB Yeats, Gerard Manley Hopkins, John Donne, Charlotte Bronte—if Verne’s Michel Strogoff was my favourite childhood classic, Jane Eyre was my teenage favourite– and the great Russian writers: Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, Chekhov, Gogol. As I was growing up in Australia, Australian classics too—I loved the works of Martin Boyd, Kenneth Slessor and Miles Franklin, for example. And also what are known as modern classics, many with a political/social tinge: George Orwell, Aldous Huxley, Ernest Hemingway, Harper Lee …as well as, by way of contrast, classic fantasy fiction: Lord of the Rings, Dracula, Frankenstein.

But it wasn’t just classics written by a single author that fed my childhood and adolescent reading: for retold fairytales and legends, Greek and Celtic myth, Norse sagas and medieval Arthurian epics, ran like glowing golden threads from many centuries past into the weave of my own imagination.

So what did reading all those classics do for me?

Read MoreI spent a month in Cambridge (UK) in May/June. It was a magical time to be there–the weather was sunny, bright, warmer in fact than I’ve ever known it in England. :-) Cambridge, always a beautiful city, looked even more stunning set against the bright blue of the sky, with flowers rioting everywhere and people in light summer clothes strolling by the river banks.

But I wasn’t only there on holiday; I was there to write. Working on my PhD in Creative Practice (which means I’m basically in the happy position of writing a novel plus an academic exegesis–a kind of mini-thesis), I was also in Cambridge as a ‘Visiting Scholar’ in the Children’s Literature Centre based within the Faculty of Education and Homerton College, which meant I could use University facilities, including the libraries, as I wished. And my time there was extraordinarily productive, despite or actually perhaps because of the many cultural, historical and natural pleasures Cambridge and its environs has to offer–and which I fully indulged in.

I worked on the second draft of the novel, added to the exegesis, wrote two short stories, and delivered both a seminar paper and a conference paper. The working environment was perfect, it must be said. Sitting at a desk in the pleasant faculty library, looking out at a lovely peaceful garden complete with the occasional visit from deer and squirrels, was a perfect spot to get into the writing mode; but so was the table in the upstairs flat we rented a block from the city center, where you could watch the world go by on their bicycle. The atmosphere of Cambridge itself is immensely conducive to both thought and relaxation; both lively and laid-back, it has an energy that feels both creative yet peaceful. And it got me thinking about how working in an unfamiliar setting, away from home, affects a writer’s work.

For me, it’s something absolutely necessary, now and again. I need to get away, far away, to recharge batteries, to be in a place I don’t know but that is full of interesting things. It feels like the green sap rising; like a refreshing drink on a hot day, with my mind and heart open and all senses prickling with awareness. Being away has often resulted, for me, in new insights, new ideas, and reinvention of old ones. Of course it doesn’t always work: The atmosphere can be wrong, life can intervene, stresses can happen. But by and large, for me it’s been a positive thing. Yet I know that for some other writers, being away from home can have the opposite effect. They need to have familiar things around them, to work in tranquility un-distracted by new experiences; not to do so can shrivel the creative urge for them.

Here, from my own experience, are a few things I’ve learned to help minimize stress and make the away-from-your-desk experience as creatively rich as possible.

Read MoreSometimes the shortest things can unexpectedly be the hardest to write. And that’s the case with author biographies, or bios for short. Bios aren’t like CVs. They’re not as formal. They are more like mini-stories. They give a flavour of the person behind them. And like query letters and blurbs, they function as ‘hooks.’

Over the course of a writing career, you’ll discover you need more than one bio. In fact, you might find that you need quite a few. Each of them will be written for particular purposes, whether that be pitching for genre-specific projects, for festivals and conferences, or for book proposals and blurbs. Each of them will have a slightly different angle, though they encapsulate the same basic biographical and bibliographical information. And though they may fall into ‘types’ of bios—ie, for publication, presentation or industry purposes—each bio is also slightly different, even within each type.

The Case of Valerie May

For a bit of fun, let’s take the (imaginary) case of Valerie May, author of romantic suspense novels who also writes the occasional non-fiction authorship book. Here are a couple of her pitch bios, one for a non-fiction book called Roses have Thorns, a practical guide to maintaining a writing career, and the other for her new novel, The Jade Peacock.

Bio A: Valerie May is the award-winning author of fifteen novels, including the internationally bestselling The Black Rose. She is the founder of Delicious Shivers, a popular blog specialising in the romantic suspense genre, and with fellow author Jenna Sims initiated the first Delicious Shivers seminar, now an annual event. Over the course of her career, Valerie May has been a bookseller, served on several literary industry committees, and been a popular speaker at conferences and festivals.

Bio B: Born in London of an Irish father and French-Vietnamese mother, Valerie May was brought up between languages and cultures and now lives in Sydney, Australia, with her family. The award-winning author of fifteen novels of romantic suspense, including the bestseller The Black Rose and its popular sequel, By Any Other Name, as well as three works of non-fiction, she also blogs regularly, and features as a speaker at literary events. Her Vietnamese grandmother’s dramatic story was the inspiration for The Jade Peacock.

These two bios have a similar structure, but a different emphasis, with each aimed at establishing Valerie’s credentials in a particular context . For Roses have Thorns, the emphasis is on Valerie’s professional experience in the book industry; but for The Jade Peacock, the bio takes in not only her track record as a writer, but also a great deal more personal information, including her cultural background which is relevant in this case. In both, the fact that she is a successful professional author is front and centre, but in the novel bio, there is a more private angle as well, allowing the reader to relate to the author as a person. Meanwhile, for the non-fiction book, her experience of the industry from different professional points of view–author, blogger and bookseller–is highlighted, and more personal information is omitted.

By the way, it’s my opinion that it’s best to write bios in third person, and to stay away from quirky bios.

Read MoreFlickr Creative Commons: thinkpanama

Pitch sessions have become a common, and popular, feature of most writer conferences and festivals. Some are private, where writers and illustrators get to present their work one on one to editors, publishers and agents; others are in public, where creators present their work to a panel of publishing professionals, in front of an audience of fellow attendees. The private sessions tend to be longer; the public ones shorter. With both types, prior preparation is the key. But on the day itself, you also need to keep in mind certain things which will help you strike the right note. Here are some tips based on my experience of seeing it from both sides of the pitch table!

Read More