Posts by Rheea Mukherjee

I’ll start this post with a disclaimer. As a fiction writer, I am drawn to writing stories that work within the realities we exist in. I’ve rarely worked with magic, fantasy, alternate world histories, or creating imaginary worlds.

Primarily, I enjoy stories of humans living in contemporary urban realities. I wanted to expand the way I wrote, but it always seemed like a struggle. Over time I made peace with it and plunged further into the kind of writer I wanted to be. I wondered why I related to books that told stories about our times, struggles, pop culture, gender roles, and other political realities.

My upbringing between two countries (U.S and India) possibly shaped how I read. The sense of displacement and mixed ideas of identity had imprinted a curiosity for people and how they could adapt to very different realities depending on circumstances. The idea that the world we relate to can be so stunningly different for another person in another country or even another city or village in the same world compelled me.

Writing in real life meant a lot of my work started to blend into prominent political stories that pointed to the limitations of colonized worldviews. The most important revelation in my writing was the understanding that all writing (whether you mean to or not) is political.

Our writing points to our worldview; who published what, and what gets published? It demonstrates our cultural imaginations, both in their glory and limitations. When I talk about this, a lot of people get uncomfortable. The idea that one is bringing ‘politics’ into writing is something only some types of writers desire. I think this discomfort exists because the concept of politics has been largely misconstrued. We believe ‘political writing’ takes a particular stance and label. It is motivated by fear that certain writing will offend some people.

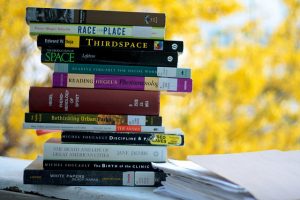

To me, politics means growing awareness of how humans experience and construct cyclical systems of oppression. Why are some stories boring to us and others amazing? For example, in a western mainstream imagination of books, main characters living in a country we know little about can be boring or not relatable unless it caters to a sense of exoticness that satisfies the way we imagine alien life to be. Indian diasporic writing was limited to only first-generation struggles for a long time. In contrast, stories set in India were limited to exotic ideas of clothing and food.

Books written from a non-first-world perspective have only a few readers who praise them for their international qualities.

Most of the world has set American pop culture and markers of the ‘good life’ as the gold standard. Most of the world is familiar with American books, movies, and music, and many know more about American politics than their own countries (and in many cases, more than Americans). Globally, there is already a pre-existing bias for us to relate to the features and realities of this culture. This isn’t so much a problem; it is a loss for us to examine the world from perspectives and storytelling styles that might take more adjustment to enjoy. I believe that reading and writing things that might seem unfamiliar to us can broaden the way we understand humanity.

I remember reading […]

Read More

In 2018, I went on submission with my first novel, The Body Myth, with my agent Stacy Testa. At the time, I was still shocked I even had an agent in New York who wanted to represent my work and had done multiple levels of edits with me over a couple of months.

I had no idea what to expect about the submissions process, but soon, I’d not only know everything the internet had to say about it, but I would become obsessed and relentless in wanting to know everybody’s submission story.

My agent was very warm. Her process was exceedingly considered and organised. She had created a list of top editors as her round one and then a couple of other publishers/editors she wanted to try if round one didn’t work out.

In the very first week or two, I got two near misses. One editor from a big five almost loved it enough but ultimately just wrote an excellent rejection. I got a couple of glowing-praise-in-some-feedback letters, but they were still all rejections. After a flurry of these nice rejections that came in very early, an eerie silence descended upon my inbox.

TLDR, we had to wait till round two of submissions and a total of 5 months before I got my acceptance from Unnamed Press. This was followed by multiple offers from all the Big 5 publishers in India, and India rights were sold to Penguin India after a 5-way auction!

Well, it’s been 3-and-a-half years since The Body Myth was published. It’s always nice to tell people your story after it has a nice enough ending. But those 5 months? They almost killed me.

I read whatever blogs were available about authors (bless their souls) who wrote about their submissions process in great detail. I even read some brave authors talk about their experience of going through the entire process and ending up having to shelve the project.

I checked my email even when I knew there was no way my agent was up (I live in India). All I knew was that my good/bad news would come by email because of our time difference. My Inbox was the alter that I paid my respect to every hour of every day.

I stalked editors on Twitter; I tried to read into random tweets. In short, I lost any reasonable sense. I did have some fellow pitch-wars authors who were on submissions simultaneously; those email exchanges were life-affirming. We could share our angst and excitement.

Finally, one night, when I least expected it, I got that mail from Stacy saying, “Great News! Read below!” and it was a note from the editors at Unnamed Press detailing why they loved the manuscript and asking if they could they set up a time to talk with me.

Now, let’s come back to 2022. After 5 months of editing and feedback with my fantastic agent, we are on submission with my second novel. Things are a bit different in how we approach it this time, but it’s still the waiting game.

Here are 3 things I know now about the submissions process that I am applying to my second novel:

1. Trust the cliché; every submission story is indeed different. The submissions process is a complex universe holding […]

Read MoreThere’s a trope we’ve all investigated in our collective culture. The idea that many great artists, creators, writers are often plagued with mental health issues. The idea that some of the greatest writers experienced unfathomable tragedies or chronic depression, and that this somehow is inextricably linked to the deepness of their work.

The idea that tragedy or chronic depression allows for better art is imprinted in popular culture to the extent, that today, we’re talking about how the romanticization of mental health might be a new toxic trap we’ve created for ourselves.

For years, I’ve thought about the intricacies of honesty. Or rather, what it means for us to have honest conversations about what art is and how it’s defined by our experiences. I have lived with moderate depression for most of my adulthood. Its worst symptoms have been stabilized for years through medication. Although bouts of incapacitating depression are few and far between for me today, I think about the imprints it has left on me as a writer. Do I tend to write about the darker elements of human experience because of it? And if so, why do most people who know me think I am a super optimist in the way I approach life?

I am coming to believe that every human being has many ways to label, approach, or deal with what we may generically call the ‘obstacles’ of life. And they all show up in what we create. Are the challenging parts of our life critical to the quality of our work?

Most of my twenties would have had me nodding in agreement. The glorification of pain was the perfect road for me. A space that offered a payoff for the trauma I experienced. A place where I could feel included and validated.

This was the same glorification that also birthed many variations of ‘inspiration porn’. A space where our human tendency for voyeurism could quell its curiosity by reading about other people’s experiences while thanking God they didn’t have to go through it. But this would be a reductionist view on its own. Because narratives about or inspired by real life trauma allows many others to resonate and give articulation to things they could not express or write about. It has allowed people to take issues like mental illness more seriously and offered new and evolving language that continue to empower people.

Now, in my late thirties, my own path with mental illness has been a negotiation of sorts. A partial rejection of the institutionalized labels and boxes it has created. A partial rejection that it is what defines me or my writing in any way. Sounds a lot like sitting on the fence? Perhaps, I find it healthier not to have a complete answer. A space where we’ve realized a lot about ourselves over time and pause now, to embrace the evolution of our thoughts to come. Much like the stories we write, they don’t have perfectly wrapped endings. Our characters and worlds, real and unreal, don’t have exact answers or explanations either.

Personally, depression has allowed me to observe people more. It made me imagine more about their circumstances; what makes them sad, driven, ambitious, happy, static, or numb? Maybe it’s a response born out of […]

Read MoreAfter more than a decade of freelancing and co-running a small boutique firm that provided creative branding services in Bangalore, I jumped ship and took my first full time job at age 37. In the past, my only full-time jobs were smaller stints I did as a social worker right after college and summer barista jobs.

Up till last month, I was a published author who had paid the bills mostly by working on my own terms with copious amounts of flexibility. But the pandemic hit, and things got harder and harder. The late and dwindling payments were not enough to stabilize even with help from my family.

It’s true that a vast majority of published/ professional writers will need a day job to support themselves. In an epically ideal world, we’d be paid well for articles, workshops, talks, and teaching stints that would all line up perfectly with our schedules. I consider myself lucky to have made most of my adult life with the ability to write and set my own hours for work that actually paid me.

This is why I resisted a traditional full-time job for years. I thought I’d never be able to adapt to a 9 to 6 job in a larger company.

Last month I got an offer to join a rapidly growing start-up as a senior content manager. The opportunity had come because of my years of experience in branding but also because of the unique insights I might be able to provide from my creative writing life.

Part of my larger resistance to a traditional full-time job was that most people in that set-up were forced to look at life through limited ideas of time management. The workday culture, in my opinion, keeps our identity and purpose latched to work. It makes tending to the rest of our life seem like just a nice notion, something you just had to do, like eat and sleep. There didn’t seem to be any room to nurture ourselves in ways outside the imagination of a weekend.

Most importantly, the full-time job aids the way our hyper-capitalistic world has taught us to be ‘productive’ and measures our worth only through these metrics.

The question that has no answer is this: Can the larger corporate world really benefit from the insights of the life of a creative writer? Can it structurally offer a space where these two divergent lifestyles can interact in a meaningful way?

There are many possible answers to this, but suffice to say that I didn’t go into this with dreamy ideas of dismantling some of the oppressive structures of larger companies. I went for two reasons. The first being my belief that I could provide value through my experience and apply it to a much larger infrastructure. And second, it would provide me with an above average paycheck that would come every month with the promise of more in short amounts of time.

The truth is, I have started this new life at a very opportune era. It takes up the time between the endless waiting a writer must live with. In July, I finished writing my second book. The time it will take my agent to read, process, edit, and then submit will take months. It will take […]

Read MoreFlickr Creative Commons: paolobarzman

Real life might be stranger than fiction, but does that mean writers should abandon plausibility?

The past year has seen me doing two things. The first thing has been coping with the pandemic during the massive COVID spike India witnessed earlier this year. The country was reeling in shock from the lack of basic infrastructure while grieving with the loss of loved ones. Of course, the world is not done with this terrifying plot; if anything we’re just getting better at living in the moment.

The second thing I’ve been doing is finishing my second novel (yes, this was the productive part of my coping). I was writing a plot that ‘could’ be the future if we didn’t take some political and social realities seriously enough. One of my characters, who in general stands up for many social issues, does something truly awful to a friend. To be honest I had a hard time trying to convince myself about the plausibility of it all, both the larger plot of the book and my character’s surprising behavior.

As if COVID as a global tragedy wasn’t enough for me to be comfortable with the idea that literally anything could happen and change everything we knew; it’s absurd really, the idea of writing a plot that might be ‘too much’ when ‘too much’ was happening all around me.

It got me thinking about our craft and our intent as writers.

When we decide to write something, we are unspooling a character or a series of events that, most of the time, says something about our humanity. Sometimes a weird unbelievable incident or anecdote comes your way, and it inspires us to write a story or a book.

I’ve been a true crime fan for a long time now. I can watch endless hours on YouTube about people who did the most horrific things without an ounce of remorse. In fact, some things that have happened in our world are far more absurd than anything I’ve read in fiction (at least fiction that stays within the realms of reality and humans).

But that’s seldom enough for you to base the entire intent and pacing of your story.

While it’s true that any wild concept can be a plot and any character can partake in something ‘absurd’, I have come to believe that plausibility isn’t the main challenge.

Our characters are more than their plot points

Write a character well enough and they tend to surprise you with what they do later in the story. Our characters are important to the life we bring to our stories. When we do them right, we also give them agency. It’s a bit of a contradiction, perhaps like God and the idea of free will (if you’ll indulge me). If we think we’ve done our best with our characters, to the point that they start doing things on their own terms, I urge you to trust that instinct. Here are some things to think about when writing your characters:

Our plot points are more than their shock value

Read MoreFlickr Creative Commons: Cheryl Foong

Everything we write whether it’s literary fiction, memoir, or science fiction, comes from the influence of our own lives. Those parts of our lives might be written in metaphors or vague references. Some of us are more direct, we write stories based on actual events in our life. We write to play and make sense of our reality.

The question I’ve been playing with? Well, what is reality? In context, especially, to us writers. Reality is our perception of the world, the priorities we arrange in our day to day existence that become most notable.

For example, someone who is caught up in the intricate details of the mundane may take note of the steam rising from a cup of coffee, the light shining off the leaf of a tree, the lines on the sidewalk. The same world might be very different for a person who is focused on climate change. Their mental and emotional bandwidth will note every plastic cup being sipped on the way to work, news headlines that catch their attention and fill their thoughts will be focused on our environment, and therefore their reality. An animal lover will notice every dog in the car, every injured squirrel, and know all the local shelters and animal-helplines by heart and therefore program their world reality with that focus. The same world can be a million things depending on who you are.

For me, this becomes a fascinating idea when it comes to the work we do as writers. We are obviously writing about things, places, and scenarios that come partially from what is most palpable to us. Readers therefore will interpret our stories with the perspective they are seeing the world with. When I wrote The Body Myth, I honestly thought most readers would pick up on a fundamental philosophical question about existential purpose. When the book was published, however, readers picked up on other elements of narrative, many of which I had not thought about myself.

I’d like to toy with the idea that writers are essentially reality expanders. Expanding other possible truths together, some of which we might never participate in.

But what happens when you as a writer truly want to use real world events: personal and political and ‘talk’ to the reader about it? How do we align with the fact that we both have complete control and no control over our own narratives?

Here are a few things I’ve been realizing and working with over the past couple of years.

Read MoreFlickr Creative Commons: gato-gato-gato

These days, I find myself thinking about my ancestors. I have no idea what they may look like. I happen to think they inhabit the air I breathe. They played many roles to get to me. This is a limited and relatively selfish perspective and yet it’s an important one to write about.

I have a lot to unravel as a person that writes.

My ancestors played a lot of roles. Some of those roles are fuzzy and unrelatable.

I am more familiar with recent generations who are seemingly more linked to the silences and traumas I have held inside me. You too will hold these stories in your flesh, in the pace of your walk, within the seconds that skip between your blinking eyes.

By now I know the ancestors that played the role of a woman had played it mostly through silence. When silence grows in you, you perform towards your world quietly, without questions.

Silence is an act of self-preservation.

I find myself thinking about their opinion of me.

Mostly because I am writing things: twisting and strangulating their absurd amount of silence into submission. Every year, I write something that surprises myself. Things like my body and its betrayals become easy to document on paper. Deconstructing my own ideas of love and my internalization of toxic patriarchy has become exhilarating painful things to write. Like picking at a lovely fresh scab.

First I’d write things, small tests, small truths fluttering about between the threads of a soft cotton veil (let’s call it fiction).

Over the years, I have opened up old wounds and let them spill into paragraph puddles. They grow into floods. I think they might drown me at first.

I know my ancestors are cautious people. They live within me and are in shock. When they see what I write their anxiety travels into my chest. When they really want to catch my attention they give me migraines. You need to really think if you can put this out there, they tell me. After all, generations of silence is a hard thing to translate. Careful.

And yet over the pandemic, when the days melt into each other, they come in my dreams. No vision, I don’t know what they look like still. But I can hear their thick whispers.

Saying:

Are you sure you want to write that? (Please do)

I don’t think you should write that (But please do)

You’ll be finished if you write that (And it must be done)

Read MoreFlickr Creative Commons: Francois Pacaud

I am going out on a limb here and going to make a small assumption. We’re all in the same boat in terms of what’s occupied most of our minds for the last couple of months. It is the first time we can collectively relate to an experience no matter where we live. We’ve been smacked down with what we thought only our imagination and ace-plotting skills could create. A world-wide pandemic that has universally changed our lives forever.

In my lifetime, I’ve had templates and past experiences to shield me from the unexpected. From physical pain, loss, grief, breakups and financial struggles, we had a certain knowing, an understanding that we will go through these things. And while all of those things are terrible (and usually make us learn something about ourselves), they are the things we’ve been socialized to accept.

What we’ve not been socialized to accept is constant uncertainty. One that only offers one certainty: that no one has a real answer. And so, as we scroll newsfeed after newsfeed that features new ways to feel uncertain, some of us might feel like words themselves are limited.

In the past month, I’ve felt like my writing can’t fully grasp the cycle of fear and the need to connect to each other at this time. In spite of this, I’ve felt that acknowledging the limitedness of words can be empowering. The idea that my words can’t ever fully explain my heart, it can’t articulate the buzz in my chest that can come from both a feeling of doom and a moment of peace. Words can’t illustrate what uncertainty has done to us on a cellular level, it can’t measure the layers of humor in the phrase ‘stranger than fiction’.

How many of you have felt multiple emotions that seem to collide into a moment, only to disappear and rapidly become another thought/feeling? I think part of this palpable anxiety is us processing uncertainty in real time. It allows us to have our own moments of clarity, breakthroughs, productivity, or better still, a space to redefine what those words even mean to us.

As someone who has always taken a spiritual lens to my existential crises, I am allowed a space to peel the layers of what I understand as ‘zen’, or rather a sense of detachment from the world while at the same time, seeing the present moment as a looping cycle of moments that can be filled with potential: to create, to feel love and acknowledge stillness. The present moment is the only space for me to take action instead of obsessing over possible actions in the future, which are, at the end of the day, just ‘stories’ we tell ourselves.

We all write from the human condition, and part of that conditioning is what is being unraveled at a time like this.

Read MoreFlickr Creative Commons: Ralf Steinberger

A universal agreement seems to be that art often comes from conflict and emotional burdens. At the very least, the process of writing holds our imagination, and part of our imagination comes from the conflicts we’ve overcome and the sense we’ve made out of our world view.

At this time, it’s hard for us writers to not be bombarded by information that is repeatedly illustrating themes of world devastation, climate change, political polarities, violence and xenophobia. The truth is that the world has always had a million things wrong with it, but our access to the news is far easier, and its immediate repercussions have never been so present.

As I write this, I have become more and more drawn towards the protests against a very bigoted law in India that threatens to tear the foundation of this country apart. As India becomes a place I don’t recognize, I find my voice through my words. I find purpose in my life as an Indian writer.

Today, I find whatever I write, whether related to the political reality, or something completely creative, is coming from a place of more defined purpose. As an intense couple of months threaten to become a new reality in the country in which I live, I’ve found a few writing truths I’ve been confronting.

What Does Your Immediate Attention Go To? Embrace It

The beauty of the world is that we are all affected differently by the same things. There are many issues that can make other people charged up, emotional, or invested but might make you yawn or disengage with completely. Generally, our culture tends to focus on why other people are so invested in things, but we rarely look at what we are invested in and why that might be. The difference in worldview is what stitches together a grand universal puzzle that all of us witness. Unless we look at the things in life that tend to make us take note and bring our emotions in, we’ll risk the potential of our writers’ voices. The human condition, especially at the intersections of identity, gender, mental health, and spirituality, are things that have always been important to me; this is why most of my work embraces these notions. It wasn’t until recently, though, that I felt the power of my voice and felt comfort in the anchoring it gave me as a writer. It doesn’t matter what you write, you could be writing non-fiction, history, science-fiction or romance, as long as you know that these are the areas you are naturally drawn to. Own the spaces and imagination that you have; the rest will evolve on its own.

Don’t Carry The Burden of Caring About Things People Tell You That You Need To Care About

Read MoreIf’ you’ve read any of my earlier posts you’ll know that I was brought up between the U.S and India. Although I’ve been back in India for the last eight years, I am very much a third culture kid. The amount of cultural perspective I’ve negotiated in my lifetime could go on for pages. Today, I want to talk about a particular learning that has informed the way I express myself as a writer.

The internet has been potently responsible for millions of people having a better understanding of their world. It’s also a space where many of us have unlearned a lot of the notions we had about issues like oppression, war, sexuality, and gender.

Cultural appropriation and social privilege have brought up many hot debates in the world of writers. As they should. After all, writing is more than storytelling, it is a political act. It doesn’t matter if we’re writing fantasy fiction or chronicling the injustices of war. Our stories, our ability to write them and gain diverse sets of readers reveal a lot. If we look closely at any piece of writing, we can see the writer in other forms: Narratives of our social locations, our biases, our curiosities about the world, and our histories all make an appearance.

How much responsibility and awareness of our social locations do we account for when we write? Shouldn’t we feel free to create and imagine whatever we’d like?

Here are three learnings and thoughts I’d like to share with you.

Accepting Our Privileges

Some social privileges are so inherent to our everyday that we don’t even see them as privileges. Take for example that we’re all on the internet now reading and engaging in the English language, a language which has the most power in global currency. Much of the world doesn’t have access to education and fewer still have access and comfort in accessing the world in English. By that fact alone, when we write, we are writing to a collection of people who interact with this basic social location. Of course, when we add race, class, sexuality, and gender, we complicate it even more. When we live with the comfort of a world that accepts and reinforces our worldview, we can’t really see how experiences for different groups of people are far more difficult because they haven’t been integrated into mainstream norms.

As writers, it’s in our best interest to deconstruct the feeling of being ‘attacked’ when confronted with our privileges. We’ll be far more imaginative and meaningful in our writing if we can be aware of them.

Checking Your Privilege Doesn’t Mean Restraining Your imagination

I’ve heard a lot of people express worry and even frustration when they discuss social privilege. They wonder if they are ‘allowed’ to write about other things, places and people that are different from them. My opinion is that you can write about anything you want, but if you do that without employing the right lens you are very quickly going to write something that is either problematic/offensive to others or you are going to take up the space of writers who are marginalized and don’t get the same platform to write about their own histories/identities. When I say that we have to use the right […]

Read MoreFlickr Creative Commons: Robert GLOD

I’ve spent my life living between India and the U.S.A. One blog post can’t begin to describe the challenges, privileges, lows, and highs of it all. I can, however, talk about being a bi-cultural writer and writing in various global dialects through one language. I am a weird kind of third-culture kid. I was born in the U.S and finished elementary school there. Then I did middle and high school in India and returned to the U.S for another 8 years where I finished college and my Master’s degree. I’ve since been back to Bangalore, India since 2011.

First, let me tell you about my accent. I code shift – my accent and cultural references can change according to country, and who I’m talking with. I still get teased about it.

Because of my experience, I see English as two very different kinds of languages: Indian English and American English. On the macro level you might think it’s just the accent that’s different, but there are more nuanced differences that are a result of specific cultural backgrounds and responses to very different realities and environments. I admit, it’s easier for me to write for a specific cultural audience. That’s why I’ve been involved with the way I think about writing for a global audience. How do I hold a place in a specific narrative and allow for people from all kinds of backgrounds to find a point of similarity to their own reality? Over the years, I’ve done a lot of relearning and decolonizing. Here are 3 important things I have learnt as a bicultural writer.

Letting Go Of Italicizing Culturally Specific Words

Growing up, I’d read Indian authors italicize or explain very Indian terms in strange ways. I acknowledge that for many non-Indian readers, if I made one reference too many to terms or concepts uniquely Indian, I would risk losing them, and worse, boring them. That said, using western-centric explanations and using italics takes away from the authenticity of the environment. I’d read ‘samosa’ with descriptions like seasoned potato filled pastry, and I’d chuckle. This is not because the description is inaccurate; in fact, it is probably the best way to explain what it is in English to a western audience, but it’s not how people raised in India would think of it.

I found authors who were owning their language with the English they spoke, offering more of a realistic picture of life in such a setting. Many Indians grew up reading British and American books with descriptions of food items we had never tasted in the 80s and 90s, and we had to make do with the names and imagine what they were. In fact, my father had grown up reading Archie Comics in India and assumed pizza to be a sweet dish. When he came to America in the late 70s he was shocked that pizza was savory! We never got explanations and we’re probably all the richer for it. While the world is a lot more globalized now and many readers are more exposed to cross-cultural habits and foods, there are still things that will be very specific to a culture and environment. It’s also the age of […]

Read MoreFlickr Creative Commons: Steve McFarland

We are so excited to welcome our newest contributor to Writer Unboxed – Rheea Mukherjee! Rheea is the author of The Body Myth, which is releasing this month from Unnamed Press. Rheea is the co-founder of Write Leela Write, a design and content laboratory in Bangalore, India. You can connect with Rheea at her website, Facebook, and Twitter.

I spent the first fifteen years of my life thinking I was quite stupid because I didn’t do well academically. It took as many years to rewire this thinking and understand how wide the spectrum of intelligence is. It took even longer to identify my own intelligence on that spectrum, which happened to be emotional intelligence. This is precisely why I’ve added quotes to the word ‘smarter’ in the title of this blog.

When I started writing my novel, The Body Myth, it quickly became apparent that Mira, the protagonist, had a certain bookish intelligence that I did not possess. Mira had read a wide variety of dense philosophical books and could link historic dates and anecdotes to present-day issues. The memory of everything she read was living and breathing and on the tip of her tongue. I panicked when it dawned on me that Mira was way smarter than I could ever be. While I had the same curiosity she had, especially about the past in context to war, oppression, feminism, and culture, I hadn’t read as fastidiously as she had, nor did I have the ability to connect the dots of the past or explain philosophical ideas and theory to a layperson.

How do we write characters that are different from us intellectually? Here’s what I did to create a character that was smarter than me, or rather had a capability that was very different from something I possessed. While the jury is still out on my success, I certainly learnt a lot about what a writer is capable of and tested my own preconceived limitations.

Study the conviction you have in your character

I didn’t make Mira smarter than I was just because I wanted a challenge. The story demanded it. Her trauma manifested as a need to validate the world through intellectualism. Her cynicism and emotional instability emerged from this form of validation. Once I knew this, I realized I had to put myself in her shoes. I also knew that it would be an artificial process for me, but one that had to flourish authentically on the page. All this to say: allow your story to demand a character’s abilities and worldview first and then research accordingly.

Prepare to temporarily rewire your brain

My process of rewiring my own mind took about 2 months. This was a period of time I filled a thick notebook with handwritten notes. I watched youtube videos on philosophy and history for hours. I read articles, processed names and dates, and jotted down eras and influencers of certain time periods. In order to soak in the information I was hearing or reading online and in print, I had to write it down. For these two months I was another person, a person […]

Read MoreBig thanks to contributor Julie Carrick Dalton for introducing us to today’s guest, Rheea Mukherjee!

Rheea’s debut novel, The Body Myth, recently sold to Unnamed Press and will be published in February 2019! She holds an MFA from California College of the Arts. Her fiction and non-fiction has been published in several publications including Scroll.in, Southern Humanities Review, Out of Print, Cleaver Magazine, Kitaab, and Bengal Lights.

She co-founded Bangalore Writers Workshop in 2012 and currently co-runs Write Leela Write, a Design and Content Laboratory in Bangalore. She is represented by Stacy Testa from Writers House.

She’s with us today to talk about an issue that, once upon a time, tested her ability to convey language and threatened her dream of becoming a writer.

Learn more about Rheea on her website and on Twitter.

The Writer Who Can’t Write

I suspect most writers knew they were meant to write before they actually did. This knowledge could have manifested in a bunch of ways. It might have been a passing idea: I think I might be good with words. It might have been a nagging voice: hey you, you’re supposed to be a writer, so write! It might have been a quick thought that was rapidly covered in self-doubt: Maybe, I can write? Nope, you suck, remember?

Or maybe you were one of the more confident ones, aware from an early age that you were meant to write and then did so without an ounce of self-doubt. (Can we meet?)

I was 14 when I first thought I could, maybe, possibly, write. But all the evidence to this was severely contradictory.

I am a third-culture kid. I did schooling in the U.S till the 4th grade and then moved to India where I finished high school. I was back in America for college and graduate school. Living in two cultures has blessed me with all sorts of empathy and boosted my writing imagination. So far so good right?

But see, back when I was in high school in India, the only exams I did well in were English and Biology. I failed most other subjects. I owe this to learning in a very rigid Indian school system while simultaneously dealing with massive cultural changes.

However, at the time, there was only one reason for my failings: I sucked, totally and completely. Why else would I fail this hard?

As a young adult, I realized that my childhood instinct was right. I was good at writing, or rather communicating a moment, time, or idea in a text.

I really was.

But the technicality of writing was something my brain did not cooperate with. And here’s where I tell you the truth.

I can’t spell. I literally cannot. I am moderately dyslexic, so I can’t see basic errors and many of my words read upside down or are missing letters even though they appear correct to me. Somehow, I had gotten away with this (via blissful ignorance and teachers who never really called me out on it) until I finished high school.

Then I turned 18 and went to college in Colorado. My 101 college composition classes were giving me a C Minus for a […]

Read More