Posts by Juliet Marillier

Let’s talk about heroes. I’m not talking sporting heroes or comic book superheroes. I’m using the term hero to mean a person of any gender who demonstrates extraordinary courage and acts in a way that makes change for good in the world. Some people, through birth or other circumstances, seem destined to live heroic lives. An unlikely hero, on the other hand, is someone whose heroism comes as a surprise to us – it simply isn’t what we expected of such a person. Such individuals appear in the oldest stories of many cultures: folklore, legends, fairy tales. From time to time they appear in our literary works. And they exist in real life, though we don’t always witness their remarkable deeds or recognise them for what they are. Sometimes our unlikely heroes just get on with what has to be done.

There’s a common pattern to this in many traditional stories. We might start with three brothers or sisters and a quest to be completed. Siblings A and B are big, strong and confident, though possibly also selfish/unkind/thoughtless. Sibling C is seen by the family as lesser – quieter, weaker, too soft-hearted for their own good, perhaps a bit of a dreamer. They may be a step-sibling or half-sibling to the others. When the challenge comes, it’s A and B who go out, in turn, to confront the dragon or find the treasure or whatever. Both A and B make errors, generally because they won’t listen to good advice, or refuse to perform an act of kindness that may stall their progress, or are so focussed on the goal that they don’t bother to pick up clues along the way. A and B both fail in the quest.

Sibling C is the unlikely hero, someone who does not display traditionally heroic attributes such as great physical strength, charisma, excellence in fighting and so on. Sibling C takes time on the journey; listens to strangers they encounter; stops to help those in trouble (old woman carrying a heavy load; injured bird; lost dog that nudges C along a different path.) Sibling C does not contemplate the reward for the task as they make the journey. C wants to do their best, and as kindness comes naturally to them, they take the time to be kind along the way. The dreamer who used to play tunes on the whistle while out tending the sheep now stops beside the track to entertain a group of travellers and is rewarded with gifts of food and information that will prove vital to the quest. Sibling C may also pick up various companions along the way, the sort of folk with whom A and B would never mingle, and they help C with the task. In the end it is the unlikely hero who completes the quest.

It’s ironic, in view of what sparked this post, that an obvious choice of an unlikely hero from classic literature is the socially awkward Pierre Bezhukov from Tolstoy’s War and Peace. As the illegitimate son of a count, Pierre unexpectedly inherits a fortune and finds himself catapulted into the upper echelons of Russian society. Over the course of the truly epic story, the reader sees this misfit character grow and shine […]

Read MoreIf there’s anything good about a creative slump, it’s the extra time it provides for reading. When I’m working hard on a manuscript my recreational reading goes down in both volume and seriousness. But over the past year I’ve done very little writing – the dire world situation has caused a shutdown of creativity, not only for me, but for many of my writer friends. I salute those who’ve managed to continue regardless.

A crisis like the pandemic may lead us to feel that our world is shrinking, and with it our opportunities. Those may be small opportunities – the ability to walk the dog whenever you like, without masking up – or big ones, such as international travel for study or employment. It’s near-impossible to make plans. It can be hard to maintain hope. That, too, can be smaller or larger scale: the hope that you may be reunited with a beloved family member, or the hope that world leaders will unite to solve the problems facing humankind.

During my fallow time as a writer I’ve done a lot of reading, and I’ve rediscovered the power of good fiction to lift us out of our everyday woes and open us up to wider perspectives of the world and the human condition. When reading the brilliant novel The Overstory by Richard Powers, I was reminded how effective a well-told story can be to convey a message – many times more so than hammering that message home in a political rant or endlessly re-stating it to an audience or readership whose attention was long ago lost. Story provides a powerful and subtle way to make a point. The Overstory is a highly imaginative, beautifully written novel about climate change and the role of trees. It’s also a skilful interweaving of several story threads whose characters we can relate to and care about. It is both entertainment and message. While conveying the terrifying truth about the way humankind is destroying the planet, this novel leaves the reader with a feeling of hope. Yes, maybe we can do something about this. Yes, it is worthwhile to keep on trying. There are good people out there making a difference, and we can be among them.

As I mentioned in a WU post a few years ago, I dislike stories that end with no note of hope or learning. I don’t mean a happy ever after; for that to occur in every single novel would be unrealistic. But I like at least one character to come out of the story a little wiser, a little more compassionate, a little more positive. A little kinder, a little more courageous. Those are the qualities we need to go on moving forward as human beings. That element of hope can be built into almost any kind of fiction, though I recognise that horror writers may find it more of a challenge. And it can be done with the most delicate of touches. I’ve just finished reading Anxious People by Fredrik Backman, a curious puzzle of a novel, at times hilarious, sad, thought-provoking and insightful. The characters are (mostly) people with whom you would not wish to be trapped in a hostage situation […]

Read More

This post is about two things: growing old and storytelling. At seventy-three I’m definitely an older woman writer, and that increasingly concerns me. Can I tackle another trilogy, or will I be too old to maintain the pace and quality by the time I get to Book 3? How do I balance that with the expectations of readers who want a book a year, delivered promptly? Is it time to put myself out to pasture? And by doing that, would I be erasing myself because of age, making my story just another in which the female protagonist must be below a certain age to be considered interesting? There is a lack of older women characters in fiction, especially in my genre of fantasy. I’ve been guilty of this myself as a writer. Many of my novels have young central characters. It’s not because I ever thought older protagonists were boring or wouldn’t sell. In the historical periods of these novels, lives were generally much shorter than they are now. Folk died in childbirth, in nasty farm or workshop accidents, in battles, or from diseases for which there were no known remedies. They were living adult lives by their early teens, and were lucky if they made it to the grand old age of fifty. It’s realistic for my active central characters to be in the age range of sixteen to thirtyish, with a sprinking of (mostly) wise elders.

I stepped out of that pattern to write the Blackthorn & Grim series, in which the two central characters are older (though still youngish by contemporary measures) and severely damaged by trauma. I loved writing that series – it was so rewarding to live the journey with Blackthorn and Grim as they worked their way out from the shadows of PTSD. Those two felt the most real of any characters I had created. But for the following project my agent steered me toward a style of story that was faster paced and featured a younger central cast. At the time I was not happy, feeling my artistic judgement and skills as a writer had been devalued. But he knows the business and his advice made good sense. We reached a compromise that satisfied both parties. The Warrior Bards series has both young protagonists and significant supporting characters who are much older, plus cameo roles for my favourite duo from the previous series.

Then came the pandemic, along with political instability in many parts of the world and the escalating climate emergency. I was not the only writer who found it difficult to be creative in a time of such uncertainty. Many of us struggled, not only to find motivation, but to deal with depression, anxiety, and other mental health issues. A year went by, and I had not only failed to write a new book, but could not even complete a book proposal to my own satisfaction. I wrote many words but they all went in the bin. And I grew a year older. I started to see people of my own age group move to retirement villages or become so frail they could no longer function without help. And I found that people who did not know me sometimes treated me as […]

Read MoreWhere do our female characters stand in history? As authors of fiction, are we bound to reflect their situation as it would have been in the (implied) time and culture of the story? What if that time and culture was one that oppressed, demeaned or belittled women? Does historical accuracy mean reduced agency for the women of our story, and how does that go down with the contemporary reader?

Whatever the chosen period, a writer of historical fiction has a certain obligation to be accurate. The reader expects the story to be true to its time, not only in the detail such as what people wore, what they ate and drank, and how they travelled, but also more broadly: politics, religious faith, education, social interaction. Then there are the big events: war, plague, drought, famine, a comet passing over, a volcanic eruption, the dethroning of a monarch. Write about a specific year and forget one of these, and readers will soon let you know about it. The strongest historical novelists know their period inside out, and can paint a compelling picture without excess detail. Story comes first; this is fiction, after all. The wealth of historical research lies behind the story, adding depth and credibility.

Much of historical fiction is set in times of limited choices for women, especially low-born women. Frequent child-bearing, hard physical labour and patriarchal cultures restricted their opportunities. With no miracle drugs to fight infection, life expectancy was far shorter than it is now. For a woman of high birth there would have been more choices – a queen or an abbess, for example, might have made opportunities not only for herself, but for other women under her control or patronage. Authors may choose to focus on fictional characters within the historical framework, allowing freer rein with the storytelling – invented characters can be given more choices than historical figures, whose lives may be well documented. But the astute reader will expect the events of the story to be possible for that time and place. Fortunately, history is full of quirks and surprises, and an imaginative writer may find opportunities for their female characters to rise above the obstacles of their time and culture.

So what about historical fantasy? What additional freedom does it allow the female character? Firstly, don’t make the assumption that because it’s fantasy, you can throw in whatever you want. “Hey, it’s not the real world, it’s got magic, who needs research?” Wrong. The world of your novel needs to make sense. That’s the first rule of world building: internal logic. Yes, you can have magic, mythology, the uncanny in whatever form you choose. You are free to change history if you wish, but to do so effectively, base those changes on a solid knowledge of the period and culture in question. In other words, learn the rules first, then break them with skill.

Read MoreI could make that title even grander by adding a subtitle: And How to Handle Them. I’ve written on this topic before. One can generalise about rejection, writer’s block, bad reviews, and how hard it is to keep going in tough times. But the journeys of individual writers are many and varied, from the one-hit wonder to the focused career writer to the newbie dipping a cautious toe in the swirling river of self-publishing while wondering whether to wait for the big mainstream deal that may be just around the corner. There are the poets, the dreamers, and the dilettantes, each following their own muse. And more, many more, just as there are many pathways in this world – from eight lane expressway to quiet suburban street, from winding country road to wee crooked track into the deep woods.

Hope, resilience, courage: these are vital for me as a writer and as a human being, and they feature in both my blog posts and my fiction. My characters meet tough challenges. Some find the courage, wisdom and inner strength to overcome their difficulties, though not without losses along the way – fantasy world it may be, but these are real people whose dilemmas are, at heart, much the same as those you or I might be facing. The protagonist may be a lonely troll princess or a medieval warrior bard or a young woman thrust into a perilous position of leadership. But their challenges are to stand up for justice and freedom; to stay strong in a hostile world; to help others; to survive; to do better. Some characters fall by the wayside, unable or unwilling to find the internal resources required. That’s how it is in real life. If I have a mantra in my work and in my life, it is ‘Be brave, wise and good and you can meet any challenge.’ Simple, yes?

Well, no. Not always. The grand title needs a third part: something about listening to your own good advice. My journey over the past year or so illustrates that. I just checked out my WU posts for this time last year and was reminded that I was working frantically on a major rewrite of my completed novel, after my editors requested substantial changes. Seems that job, done while the pandemic was raging and world politics were especially turbulent, had a bigger impact than I realised. I completed the revision on time and to everyone’s satisfaction except perhaps my own. But what came next was … nothing much.

Ever since I began writing full time nearly twenty years ago, I’ve submitted a novel every year, then immediately started something new. Some years I’ve completed a side project as well: an audiobook exclusive; a collection of short stories. So what happened in 2021? It’s July already, and although I’ve written two short stories, one already published, one coming out later, there’s no new novel. Instead I have three different book proposals in front of me, none of them ready to go to my agent yet. What went wrong?

Read MoreI’m writing this close to International Women’s Day. I’ve blogged elsewhere about the vile sexist culture that’s recently been exposed within Parliament House here in Australia, and the realisation that in many ways we’ve gone backwards since the changes wrought by the Women’s Liberation Movement in the Sixties and Seventies. Having vented my fury on that matter, I want to make today’s post a celebration of women in storytelling, both those who tell the stories and those who appear in them. So here are two of my favourite books featuring great women characters, and two of my favourite female characters from (ancient) story.

The last two novels I read for pleasure just happen to meet the requirement perfectly – both have strong, interesting women in the central roles, and both are brilliantly written. Hats off to Alix B. Harrow for The Once and Future Witches, described by author Laini Taylor as ‘A gorgeous and thrilling paean to the ferocious power of women.’ Focusing on a memorable trio of sisters and set in 1893 in a town called New Salem, this story sees the gradual rediscovery of near-forgotten women’s magic, which is put into service to support the suffragist cause. It’s powerful, engaging, and highly original, drawing the reader right into the heart of the story. In the alternative history that underpins the setting, the magical elements are entirely convincing. Although the focus is on the sisters and the women they recruit to their venture, the author does not overlook the fact that men, too, can be strong advocates for women’s rights. This is a cast of individuals, not stereotypes. And while the story’s message is a strong one, it’s never hammered home. A perfect example of ‘show, don’t tell.’

I’ve just finished reading The Ruthless Lady’s Guide to Wizardry by C. M. Waggoner. I loved this author’s first book, Unnatural Magic, and I found her second equally engaging – this was the perfect antidote to my anger and distress over the political debacle of recent days. Waggoner’s novels are set in a beautifully imagined secondary world where trolls are the wealthy, educated class and humans the ordinary working folk. Those who have read Unnatural Magic will be delighted to find a link between the two books, though each is a stand-alone story. Petty con artist Dellaria Wells, desperate for funds, talks her way into joining a motley crew of women bodyguards, hired for their martial or magical abilities. Their job: to protect a young lady in the time leading up to her marriage. But there’s hidden peril and things soon get both dangerous and complicated. The witty writing is an absolute delight. We experience every high and low, every moment of self-doubt, kindness, misunderstanding and terror with our characters. I loved flawed protagonist Delly and her half-troll comrade Winn, but my favourite character was a skeletal reanimated mouse named Buttons.

Read MoreLast night I sent an email to my editor, to which was attached the revised manuscript of my novel. The last six weeks have passed in a blur. I’ve been hunkered down dealing with a structural report that required rewriting large portions of the book, while beyond the insulating walls of my workspace the world was growing ever crazier, or so it seemed. I had to apply strict limits on my engagement with news media, despite the urge to tune in frequently and find out what bizarre thing had happened now. (The answer usually was, something even less believable than what happened yesterday, or an hour ago.) Truth really has become stranger than fiction: the current wild ride of US politics; the dog’s breakfast of Britain’s departure from the EU; the failure of some world leaders to act effectively when the looming disaster of climate change is staring them right in the face. Not to mention a global pandemic. People behaving badly. People eager to believe and promote blatant falsehoods. People turning irrational when asked to obey lawful instructions. Weird. Terrifying. And yet we can’t look away. Like it or not, this is the world we live in.

I wanted to know and I didn’t want to know. The workspace with its clearly defined project, its tight deadline and its isolation from the outside world became something akin to the cave of a hibernating creature in winter, except that instead of sleeping I was immersed in the world of the book, wrestling with the dilemmas of my characters, dealing with the logistical and continuity problems of a major rewrite, and keeping to a timetable that governed my waking hours. I was not in pandemic lockdown. But I was largely absent from the outside world, with my faithful writing companion, the old dog, pretty much my sole source of social interaction.

Of course, social media is always only a click away when you’re writing. And social media means wall to wall coverage of world events, ranging from the professional and well-informed to the wildest of incoherent rantings. Yes, I did check from time to time. How could I not? The news was like a compelling horror story that a person doesn’t really want to read, but keeps on reading anyway to find out just how horrific it can get.

I don’t often read the horror genre for entertainment. Such terrible things happen in real life that I have no wish to delve into fiction for more. Based on the same argument, I almost never write horror. All my work demonstrates my belief that justice, wisdom, courage, compassion and empathy still exist in our flawed society and can win out over cruelty and oppression. Whether it’s as small as one person performing an act of kindness and understanding, or as big as Greta Thunberg’s wake-up call to the world on climate change, every positive act counts.

Read MoreI’m not a hoarder. But some items are hard to give away. Books in particular. I try to limit new acquisitions to ebook format, but I do love the heft and character of a print edition. And as I spend a lot of hours gazing at the screen while working as a writer, it’s good to give my eyes a break when reading for pleasure. My house has multiple bookshelves in almost every room (the bathroom wouldn’t be kind to them.) My collection includes some precious old editions that belonged to my mother, among them The Golden Staircase: Poems for Children (1906), whose colour plates I remember vividly from childhood. The Golden Staircase contains such classics as Wordsworth’s Lucy Gray (who wandered out in a storm and was lost forever, but maybe still haunts the moors) and The Forsaken Merman by Matthew Arnold. Its dramatic illustration of the merman and his children reaching out from the waves for their lost human wife and mother is an old friend – when young, I could probably have recited the whole poem by heart. We were, and are, a family that values and enjoys reading.

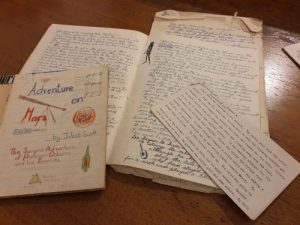

I recently came upon a box of juvenilia: examples of my childhood writing, mostly in small lined exercise books. Some were written in pencil and are now faded beyond reading, but most are in pen and ink or typed neatly on a manual typewriter by my mother, who was always supportive of my efforts. So we have the story about killer robots, written at around age 8. It’s dramatic and bloody, but ends well when the practical kid saves the day. We have two adventures of Professor Frank Osborne, Naturalist, in which he firstly discovers prehistoric life in the fiords of New Zealand, and later goes on an expedition to Mars. The first story has a great conservation message. The second lacks scientific accuracy but I remember that my friends enjoyed it. That story, written when I was 11, includes not only a mad Russian scientist but a cat who stows away on the spaceship and has kittens during the voyage. After that, I suspect someone challenged me to write what I knew, as there’s a story about difficulties among school friends and another starring a pet rat (I had one at the time.)

The writing of slightly older Juliet reflects what I was reading at age 13-15: historical fiction by authors like Rosemary Sutcliff and Geoffrey Trease, along with myths and legends. I started experimenting with style and structure, sometimes quite well, sometimes not. It’s fascinating and salutory to revisit those early efforts. I see a nascent author there, and I remember how a story idea would grip me and refuse to let go until I got it down on the page. No wonder I had rather a limited social life as a teenager!

But then … I stopped. I didn’t do any creative writing from my mid-teens until my mid-forties. Instead I pursued a career in music, raised a family, made quite a few wrong turnings, and generally grew up a lot more. I kept on reading; fiction was a great solace and strengthener, especially when real life got too hard. I learned about being sad and angry and […]

Read MoreMy first novel had a single first person narrator throughout. It was the ideal choice, since the book was loosely based on a fairy tale in which the central character is mute for much of the story (think Jane Campion’s wonderful movie, The Piano.) First person allowed the reader into her thoughts and feelings, and meant we could walk her journey alongside her. I kept the same pattern for the rest of that series, with a different narrator in each book.

I love the immersive feel of a first person voice, but of course it doesn’t suit all stories. First person is intimate, bringing reader and character close. If the narrator is unreliable, first person can draw us in, then deliver a big punch when the truth becomes evident. But it does give a very tight focus to the story, the only ‘live’ scenes being those in which the narrator is physically present. If there’s only one narrator, other characters are denied a point of view, making it trickier to show their thoughts and feelings. Devices such as dreams or visions do provide a vehicle for such insights, especially when writing fantasy, in which the uncanny is usually present in some form. I made use of psychic connections between some characters in that series.

Later on I wrote novels on a more epic scale, with a bigger cast and a wider geographical reach. Third person was a better fit for those. I gradually learned that with clever use of tight third person rather than distant third or an omniscient view, a writer can create the huge canvas of a saga while also allowing the reader deep into the minds of the main characters. With each new series, I set myself some further challenges and tried out different techniques. I noted how brilliantly some writers use structure and voice in the service of storytelling. As I continue writing, I keep on learning. I’ve moved gradually toward a structure in which a small cast of central characters takes turns narrating in first person, chapter by chapter. This approach can also work well with tight third person, in the right hands – an excellent example is Joe Abercrombie‘s The First Law series.

At present I’m putting the finishing touches to the last book in my current trilogy, a historical fantasy series called Warrior Bards. Those of you who write trilogies will know about the challenges of the third book, in which the writer must tie up the threads of two stories to the reader’s satisfaction: the one-book, stand-alone story, and the over-arching series story. In this series I have a trio of central characters narrating chapters in turn. Braiding three strands is relatively straightforward, even when those three strands don’t match (characters are individuals.) But what if the story takes those three strands in different directions? What if it’s necessary to add a fourth narrator? How can this become a neatly woven, coherent story?

In this book, the over-arching story requires my narrators to be separated for a long stretch of chapters. Not only are they physically apart, but they can’t easily send messages. This story is set long before the time of motorised transport and lightning-fast communications. Then […]

Read MoreHere’s a story about a little dog named Pippa. Pippa is a Miniature Pinscher, a breed originally designed for rat catching. Although she is very small – 2.8 kilos or around 6 pounds – she has the temperament of a mighty hunter. Or maybe Queen of the Universe might be more appropriate. (And yes, this will eventually come around to writers and writing.)

As a small puppy, Pip was given to a gentleman named Leonard as an 80th birthday gift. The giver was his friend Reg, who knew Leonard was lonely living on his own. Leonard named his puppy Pipsqueak after a character from an English cartoon he’d enjoyed in his youth. For the first four years of her life, Pip was a beloved companion to Leonard, who hand-sewed a wardrobe of little coats for her, fed her copious amounts of treats, and took her by car to the riverside park every morning for a little stroll. I got to know these two during those outings, as that was my local park and I also had a Min Pin.

Pip was not a sociable creature, but because my dog was of her own kind she accepted us. While Leonard chatted to me and his friend Reg, who had his own car and tiny dog, Pip would guard her man and his vehicle, seeing off both humans and canines with her mighty yap.

Then one morning, down by the river, Leonard and Pip were not there. Reg and I wondered about his absence, then went our ways. The next morning, still no Leonard. Reg had a key to his friend’s house and said he would check on him.

It was several days before I saw Reg again. He had both his own dog and Pip with him, and I learned a sad story. Leonard had collapsed on the floor of his home after a heart attack. For more than 24 hours he’d lain there semi-conscious, while Pip kept watch over him. After Reg found him Leonard was rushed to hospital, but he died a few days later. And while Reg took Pip home with him, he could not keep her as he was already breaking a ‘no dogs’ rule at his accommodation by keeping one. Two would be impossible.

Nobody in Leonard’s family was prepared to take Pip. Of course, I said she could come to me. I lived close to the familiar meeting place, I had a little dog she liked, and it seemed a kinder prospect than surrendering her to a rescue for rehoming. So Pip came to live with us, bringing her collection of cute coats and her imperious temperament. Her life had been turned upside down.

Fast forward eleven years, and Pippa (this became her official name when I adopted her) is an old lady of fifteen. She’s been with me nearly three times as long as she was with Leonard, but I have absolutely no doubt that in the afterlife she will leap straight into his arms with never a backward glance. She had to adapt to many changes when she came to my household. Treats on demand were no longer a thing. Guarding the car did not count as exercise. And she had to live with a changing crew of adoptive […]

Read MoreAt a launch event in London some years ago, where my publisher was featuring several new releases, one of them mine, I first heard the term ‘consolatory fantasy.’ How jarring and condescending it sounded, even though the much-respected speaker was possibly not referring to my work but making a general comment about the genre. By nature an introvert and then relatively new to such public events, I remember wishing I could retreat to a warm burrow and sleep until the launch was over. The term has stayed in my mind for a long, long while. So what is consolatory fantasy, or indeed consolatory fiction in any genre? Isn’t consolation a good thing? Don’t we generally want to feel better after reading fiction?

I hope I’m wiser now. I’ve built a solid career as a writer of historical fantasy. Made my mistakes, learned my lessons. Criticism still stings, but I’ve become better at weathering it – something we all need to do to survive in this business. The fantasy genre comes in many shapes and forms, and I celebrate its breadth and diversity. Fantasy is built around the ancient bones of storytelling: the myth, the fable, the fairy tale, the ghost story, the quirky scrap of folkloric wisdom. They are the raw ingredients that go into our cook pot or cauldron or baking dish, but each of us blends them differently, and each of us adds our own secret herbs and spices. Every dish is different. Every dish has some of the old and some of the new. Some of grandmother’s wisdom, some of the crazy world around us, perhaps a pinch of what we see in our children and our grandchildren. We may choose to set our stories in an uncanny version of the here and how, and see them called urban fantasy. We may set them in imagined worlds or in alternative history, or perhaps in a more magical, mythical version of real history. Or in the future. Label them as you will.

The Shorter Oxford English Dictionary defines consolation as “the alleviation of sorrow or mental distress.” These days I know from experience that reading fantasy – and reading in general – can indeed alleviate sorrow and improve mental health, and I delight in that. I’ve often blogged about the wisdom contained in those bare bones I mentioned above: folklore, fairy tale, myth and so on. Such stories were told and re-told for a reason: entertainment, sure, but also to pass on a message, something that would help people cope with the challenges of everyday life, large and small. Yes, those tales were full of unlikely, strange and magical things – the fiery dragon, the people who could fly, the mushroom circle that was an opening to a different world. Those fantastic elements grasped the listeners’ attention and kept them enthralled. But the stories also held something far deeper and more important – wisdom from the forebears on how to live your life safely and well. How to be brave. How to look and listen before making judgments. All manner of useful advice.

Now, those bare bones can be used by today’s writer in as many different ways as there are fish in the sea, folks. Are they all consolatory? Or […]

Read MoreIt’s been a crazy season in what increasingly seems a world turning mad. Here in Australia we’ve had fire, we’ve had flood, and now we have pestilence in the form of the COVID 19 virus, which has caused extremely varied responses in different parts of the world, from the rapid, drastic and effective (China) to the inappropriate-verging-on-ludicrous (Australian shoppers fighting in the supermarket aisles over supplies of toilet paper.) Underlying all is the looming threat posed by climate change – odd how many people are super-stressed about the virus but give no thought to the fate of the planet. Human behaviour is indeed weird. At times like this, we see the best and the worst of it.

Writers are observers. We use our observations to put flesh on our characters and make them real, from the individual who responds to a crisis by becoming a hero, a guardian, or a wise nurturer, to the person turned by challenge into a shouter, a denier, blind to all but their own perceived needs or entitlements. Ever since the first tales of wonder were shared around the fire to keep the shadows at bay and to help people live their lives bravely and wisely, stories have grown from the raw materials of real life. And boy, do they contain the good, the bad, and the ugly.

What message would I put in a story to tell around tonight’s camp fire? Sometimes the shadows press very close. Sometimes those who bear responsibility for supporting us through our challenges – certain world leaders, I’m thinking of you – seem entirely inadequate to the task. Sometimes genuine wisdom is ignored. Often, fear renders people deaf to reason. There are fine human beings among us. Every day we hear wise words, see brave actions, discover unselfish, caring souls. Here and there we see shining examples of leadership. Balance that against a cacophony of voices fuelled by political or business agendas, entrenched prejudice, personal resentments or plain terror of the unknown. There should be a perfect story for this time in history. Aren’t those old tales all about facing the monsters bravely? Aren’t they designed to open our minds to possibilities and help us learn?

Read MoreAt the time I write this, Australia is burning. I’d planned to post on a different topic, but I can’t get my mind off the fires that are eating up our forests, killing wildlife, domestic animals and humans, destroying farms and small towns and livelihoods, and filling the air with choking smoke, even in cities like Sydney and Canberra. This cataclysmic event dominates our media. There are the dramatic stories – evacuations in small boats through a thick smoke haze under a dark red sky; heroic deeds by our firefighters, many of them volunteers; the woman who carried a burning koala to safety, wrapped in the blouse she had stripped off. (The koala was transported to a wildlife rehabilitation centre but later died of its injuries, one of many thousands of innocent lives lost.) There are the tragic stories – a woman dying of a heart attack after being evacuated from the smoke zone; a father and son, both pillars of the community, perishing in their car on a lonely road; a farmer weeping as he shot his burned cattle one by one.

I live on Australia’s west coast. There are fires here too, but (so far) not on the same scale as those in the east. I won’t launch into a political rant about our current federal leadership – this is not the place for that. But people are angry. They’re furious. And people are hurting. Not only those who have suffered personal or business losses, but also those of us struggling to accept the destruction of habitat that will take many, many years to regenerate, if indeed it can, and the mass deaths of our native animals and birds, with some species likely to become extinct. This could have been ameliorated, if not prevented, had our leadership heeded wise advice on climate change years ago. They also might have agreed to a meeting requested by concerned fire experts after last year’s unusually hot summer. That they did neither is hard to accept. I’ll allow a more informed and more fluent voice to speak for me about this.

On the heels of this disaster comes rage, and with it despair, anxiety, and often a feeling of helplessness. The scale of the destruction is so vast, and without insightful leaders I doubt our capacity to prevent a recurrence next summer, and the next, until there’s nothing left to burn. It’s all too easy to lose hope, and with it the will to act. So what can we as writers do to address such a situation?

Read More