Posts by David Corbett

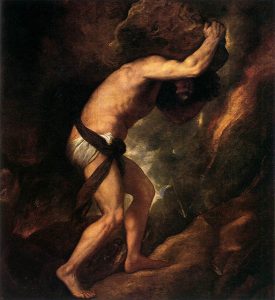

In a recent piece in Foreign Policy magazine (“The End of History is the Birth of Tragedy”), the authors, both professors of strategic studies who have served in government—i.e., members of the “Washington elite,” by some lights—argued that, “Americans have forgotten that historic tragedies on a global scale are real. They’ll soon get a reminder.”

The article drew parallels between tragedy as an art form and public policy, so as a writer I was naturally intrigued. But although I found the article rich in food for deep thought—some of which I hope to bandy about here—I found other aspects puzzling.

The authors argue for an aesthetic that recognizes humanity’s own role in creating disaster, without which whole civilizations fail to recognize the potentially cataclysmic consequences of their own actions. With this I could not agree more wholeheartedly.

The prime example they provide is Athens in its Golden Age, the 5th century B.C.E., a culture that first developed the art form we now refer to as tragedy.

“This tragic sensibility was purposefully hard-wired into Athenian culture. Aristotle wrote that tragedies produce feelings of pity and horror and foster a cathartic effect. The catharsis was key, intended to spur the audience into recognition that the horrifying outcomes they witnessed were eminently avoidable. By looking disaster squarely in the face, by understanding just how badly things could spiral out of control, the Athenians sought to create a communal sense of responsibility and courage and to encourage both citizens and their leaders to take the difficult actions necessary to avert such a fate.”

There are at least two problems with this example, however.

One is its misunderstanding of what Aristotle meant by “catharsis.” The authors aren’t alone in this, of course, because Aristotle wasn’t perfectly clear. Arguments over that particular definition have been virtually continuous ever since he made it. I’ll have more to say on that below.

The second misunderstanding is one that, to their credit, the authors themselves recognize. The “tragic sensibility…purposefully hard-wired into Athenian culture” by Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides, among others, hardly spared their native Athenians from making horrible blunders.

Athens lost the Peloponnesian War, though the cost of the decades-long conflict, not just in terms of money but men and resources and influence, proved so draining to both sides that Sparta, the nominal victor, also fell into irreversible decline.

And how exactly did that come about, and what did it look like? For that we need to turn to a historian, Thucydides, not a tragedian:

“Love of power, operating through greed and through personal ambition, was the cause of all these evils. To this must be added the violent fanaticism which came into play once the struggle had broken out. Leaders of parties in the cities had programs which appeared admirable – on one side political equality for the masses, on the other the safe and sound government of the aristocracy – but in professing to serve the public interest they were seeking to win the prizes for themselves. In their struggles for ascendancy nothing was barred; terrible indeed were the actions to which they committed themselves, and in taking revenge they went farther still. Here they were […]

Read More“What do you think is the world’s most recognizable container of information? It’s the human face.” –John Chipchase, consumer behavior analyst

People don’t just recognize us over time because of our faces; from the very start, it’s the first and primary fact they use in trying to understand us. Yes, it’s mixed in with a lot of other data—sex, height, build, posture, gait, tone and timbre of voice, diction, dialect, clothing, style, complexion, general health, odor (or, hopefully, fragrance). But it’s the face that seems to capture our essence best.

And though there are certainly types of faces—a fact that often conjures that eerie sense of having seen a certain person (or her twin) before—there is also a quality about the human face that far more often distinguishes the person to whom it belongs with unique specificity. We can’t imagine anyone else looking exactly that way.

To know the face is to know the person. Our faces are the roadmaps of our lives—they reveal our lingering innocence and hard-won experience, our openness and suspicion, our capacity for laughter, our bitterness, our anxiety, our lightness of heart.

And yet the ability to describe the human face in fiction seems to be, if not a dying art, at least in a state of decline, even indifference. And given the face’s importance in our understanding of each other, this seems like a significant lost opportunity.

Why has this happened?

Read MoreI’m going to tell you something: thoughts are never honest. Emotions are.

—Albert Camus

I’m wading into tricky waters today. If I’m successful, I will have begun a discussion on a topic that is very dear to one of our own, the esteemed and estimable Donald Maass.

If I’m not so successful, I will have stumbled, fumbled, and bumbled into an area that Don understands far better than I do and will have made a flaming bozo of myself.

Sound like fun?

Here goes.

I’m going to refer to two posts here at Writer Unboxed, one by Don titled “Third Level Emotions,” and another concerning his upcoming book, The Emotional Craft of Fiction.

I’m also going to refer to a talk he gave at ThrillerFest two years ago titled, “Why Your Thriller Isn’t Thrilling.”

In each of these, Don addressed a subject of great importance to him in his evaluation of what matters in fiction: the portrayal and evocation of emotion.

My perspective on this: I have been puzzled by what at times has seemed to be a blurring of the line between emotion and feeling.

As I wrote in The Art of Character:

The difference between emotion and feeling is more one of degree than kind. Feeling is emotion that has been habituated and refined; it is understood and can be used deliberately. I know how I feel about this person and treat her accordingly. Emotion is more raw, unconsidered. It comes to us unbidden, regardless of how familiar it might be. Rage is an emotion. Contempt is a feeling.

[For a more detailed, neurological discussion of this distinction, see “Emotion and Feeling” in Descartes’ Error by Antonio R. Damasio.]

Both emotion and feeling are essential in fiction. But given the distinction between them, rendering them on the page requires different techniques. And that’s where, perhaps, Don and I have differing perspectives.

Read MoreI have had the hardest time trying to figure out what to write for this post.

Part of the problem is that so many other Unboxers have written so well, so honestly, and so inspiringly about the deep and troubling things that are on many of our minds.

Jael McHenry, Donald Maass, and Lisa Cron, in particular in just the past week or so have touched on politics, personal purpose, and story as a source of meaning, respectively. And those posts have invited such generous, insightful comments from all of you that it seemed a great deal of what was on my mind concerned ground already covered–not just well, but brilliantly, movingly.

Part of me wants to answer the bell and add my own rallying cry (How about a discussion of George Orwell’s “Why I Write?” Um, no.), while another wonders if we all aren’t now just a wee bit spent, and could use a moment of respite, or a palette cleanser, or just a decent joke.

For those hoping for Door #3:

Angela Merkel arrives by plane in Paris and walks up to Passport Control.

“Nationality?” asks the immigration officer.

“German,” she replies.

“Occupation?”

“No, just here for a few days.”

As a palette cleanser, I considered writing about the lost art of memorization, or some nerdy, specific element of craft, like how to handle Free Indirect Discourse. But I couldn’t convince myself anyone would really want to plow through any of that, especially given the general gestalt. And I couldn’t really rev myself up to write it, either. (Maybe in 2017, when the dust settles … Will the dust ever settle?)

A moment of respite isn’t really allowed. As much as I might like to hang up a sign reading “Closed for the Holidays,” I doubt Therese would humor me (which testifies to her wisdom).

Finally, I realized I was experiencing writer’s block, which is interesting because I’m finally hitting my stride with the new novel and the pages are coming much more easily and readily than before.

So why the logjam here?

Read MoreEvery August, my wife and I travel to Turkey and stay at a vacation house her parents own near the bayside city of Çeşme.

In addition to the expected pleasures of visiting family, sunning, swimming, watching the remarkable sunsets, and eating great food—boyos (think of a dense, biscuit-sized croissant), gevreks (the bagel’s leaner cousin), sucuk (spicy sausage, usually eaten in a sandwich with a pigeon-shaped roll called a kumru), kofta (Turkish meatballs), lokma (Turkish donuts), stuffed mussels, fresh sardines, and the most amazing figs, olives, melons, and peaches known to mankind—beyond all of that, the one great joy both Mette and I look forward to in Çeşme is one I think most Unboxers can appreciate.

Reading.

Specifically: beach reading.

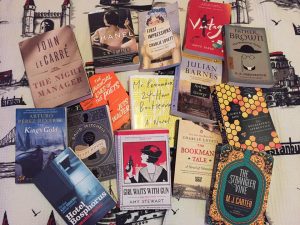

The picture below represents the books Mette managed to devour while sunning herself on the warm white sand. (She’s the kind of reader every writer dreams of.)

My haul was significantly less impressive, but what I lacked in numbers I tried to make up for in heft (he says heftily).

Basically, beyond a series of articles on political theory and histories of the Apache and Afghan wars (they’re strangely similar), I principally focused on one book—Jungian psychiatrist James Hillman’s The Soul’s Code: In Search of Character and Calling—and a lecture series from the Teaching Company titled The Modern Intellectual Tradition: Descartes to Derrida.

Now wait, wait—before you doze off—I will admit my approach to beach reading may seem a bit stodgy, but both the book and the lectures made a significant impact on my understanding of character and characterization.

Allow me to explain.

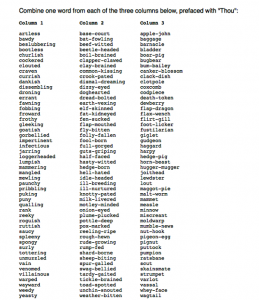

Read MoreHow to Make Your Own Shakespearean Insults:

My last few posts have been pretty heady-and-heavy, so I thought I’d lighten up a little this time around and play with language a bit.

Specifically, I wanted to talk about neologisms (invented expressions) and linguistic holes (understandable concepts for which our language lacks a word or phrase).

In some ways, these are two sides of the same coin–the use of language to express the seemingly inexpressible.

Neologisms seem the special province of writers, for who delights more in creative language than we do?

Shakespeare is hands-down the champion in this regard, as demonstrated by the now-famous worksheet for creating one’s own Shakespearean insults that sits atop this post. (Warning: prepare to get lost for a while, thou pribbling, motley-minded puttock!)

Read MoreLet me kick things off with blasphemy: Conflict is not the engine of story.

Allow me to explain.

The longer I teach, the more writing texts I seem to read, if only to find out if someone else has a clearer, simpler, or more insightful way of presenting the material. (To my chagrin, that’s often case. Fortunately, I’m not too so old a dog that I’ve forsaken new tricks.)

In some of my recent reading, though, I’ve detected a bit of an uproar over the supposed centrality of conflict in our stories.

Ursula Le Guin, for example, in Steering the Craft, takes serious issue with the “gladiatorial view of fiction” that the seemingly obsessive focus on conflict has nurtured. She considers this a kind of tunnel vision that minimizes depth and complexity, “just the stuff that makes a work of fiction memorable.”

Le Guin herself noted that though Romeo and Juliet revels in conflict, that isn’t what makes it tragic. “Conflict is [just] one kind of behavior. There are others, equally important in any human life, such as relating, finding, losing, bearing, discovering, parting, changing.”

Though Romeo and Juliet revels in conflict, that isn’t what makes it tragic.

Debra Spark, in Curious Attractions: Essays on Writing, chimes in by noting that the centrality of conflict has been with us since Aristotle—the terms protagonist and antagonist both derive from the Greek word for conflict, agon, which the Greeks considered a fundamental aspect of existence—“but it doesn’t account for the emotional power of fiction as much as its forward motion.”

Spark adds that even Janet Burroway, who in her widely read and hugely influential Writing Fiction stated baldly “a story is a war,” nonetheless qualified this statement in later editions, noting that it’s a story’s “pattern of connection and disconnection between characters” that provides “the main source of its emotional effect.”

Rosalie Morales Kearns, in her essay, “Was it Good For You? A Feminist Reflection on the Pleasure of Plot,” revealed that Burroway in the third edition of Writing Fiction actually identified birth as an alternative metaphor to battle for story structure, and that though birth also suggests struggle, “There is no enemy.” Rather the story’s forward movement resembles a “struggle toward light”—understanding, experience, wisdom.

But if conflict doesn’t drive the story, what does?

As noted above, Debra Spark remarked that conflict, despite its limitations in providing emotional power, does largely account for a story’s forward motion.

I respectfully disagree.

Read MoreOne of my favorite quotes about writing is this one from Saul Bellow:

“Writers are readers inspired to emulation.”

That notion calls to mind three recent posts here at Writer Unboxed: one by Dave King on how much he’s learned about dialog from Aaron Sorkin; a second by Kathleen McCleary on how incredibly helpful reading fiction has been for her current work in progress; and just yesterday Greer Macallister’s exploration of writing lessons to be learned from the hit play Hamilton.

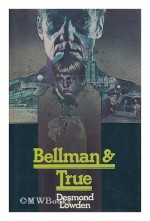

Accordingly, I’ve decided to provide my own contribution to this emerging mini-genre, and discuss a book I return to often for the numerous lessons it’s offered.

The novel is titled Bellman & True, written by British novelist and screenwriter Desmond Lowden. He adapted the book into a film of the same title (follow this link to watch the trailer), and that title comes from an old Cumberland song, “D’ye Ken John Peel,” specifically the lyric:

Yes, I ken John Peel and Ruby too.

Ranter and Ringwood, Bellman and True.

From a find to a check, from a check to a view,

From a view to a death in the morning.

There’s a pun in the term “bellman.” Above and beyond its use to denote both a hotel employee and a town crier, it ‘s also criminal slang for someone who specializes in getting past bank alarms.

Read MoreIn my last post, I talked about how to dramatize a character’s escape from the haunting effects of shame or guilt by seeking to regain the respect or obtain the forgiveness of the person most centrally connected to the humiliation or injury.

As I noted in the piece, however, and as many of you noted in your comments concerning your works in progress, it’s often impossible to achieve that respect or forgiveness for several obvious reasons: the person who can grant the reprieve is unwilling or unable to do so. Perhaps the person is dead. Maybe he’s hard of heart. Perhaps the events triggering the shame or guilt are so extreme that forgiving or forgetting is out of the question.

As I reflected on all this after the earlier posting, it occurred to me that many of the situations one encounters, both in life and fiction, are of this type, where there is no one person whose respect or forgiveness can complete the arc of transformation.

So what does a person—or a character—do in such a circumstance? How does one remove the stain of guilt or the cloud of shame when there is no one to turn to for clear-cut absolution?

A similar issue arises when the wound crippling the character’s soul isn’t caused by shame or guilt, but loss. How does one return to a “state of grace” when death, betrayal, rejection, illness, or some other misfortune turns one’s focus away from pursuing the promise of life, and instead points it toward protecting oneself from the pain of life?

The answer, interestingly enough, lies with the love story.

Read MoreTwo Santas and a Penguin Walk Into a Bar by MrBrown001

It’s the holiday season, which means it’s time to talk about my three favorite elves: Shame, Guilt, and Ho-Ho-Hope.

Those of you who follow this blog daily probably have gathered already that I’m going to follow up on two recent thought-provoking posts, one by Tom Bentley (“Shatter Your Characters”) on using shame and guilt to deepen characterization, the other by Donald Maass (“The Current”) on the implicit presence of hope running through all great stories. (If you missed either of these posts, I enthusiastically urge you to go to the links and check them out.)

What I will try to add to these two discussions is a technique for dramatizing shame and guilt in such a way that they provide not just elements of character, but generate an impetus toward positive action in the hope of some redemptive conclusion—a decisive act that seeks to remove the stigma of shame or guilt that is haunting the character’s life.

To do that, let’s revisit shame and guilt, and try to define them a bit more suitably for the purposes of writing dramatic fiction—by which I mean try to think about them in ways conducive to generating action, not just a sense of sin or self-loathing (two telltale reminders that Santa is, indeed, making a list).

Read More