Posts by David Corbett

Hi, David Corbett here. This month I’m handing the wheel over to Laurie R. King, a dear friend and the New York Times bestselling author of 27 novels (two series and several stand-alones) and other work, fiction and non-fiction. She has some excellent advice to share for those of you considering a mystery series.

Laurie’s fiction includes the Mary Russell-Sherlock Holmes stories (from The Beekeeper’s Apprentice, named one of the 20th century’s best crime novels by the IMBA, to this year’s Riviera Gold, due out this week), as well as a modern-day series featuring Homicide Inspector Kate Martinelli of the San Francisco Police Department. She has won an alphabet of prizes from Agatha to Wolfe, been chosen as guest of honor at several crime conventions, and is probably the only writer to have both an Edgar and an honorary doctorate in theology. She was inducted into the Baker Street Irregulars in 2010, as “The Red Circle.”

Take it away, Laurie.

* * * *

Ah, there’s nothing like writing a mystery series. Standalones require so much work—reinventing the world each and every time. New characters, new situations, like moving house with every Page One. But a series is like a family reunion (even, as these days, a virtual one), right? You make yourself comfortable, you settle down, you prepare to catch up…

Well, it is true that devoted readers like to revisit familiar characters. And it’s true, some bestselling series novels are more or less interchangeable, with the ritual of the plot and fight scenes and banter giving precisely what people want.

Still, sometimes the reader (and more often, the writer) wants a change—but one that isn’t a change. Something in the same general world, yet new and enticing and fresh. I know that the times I’ve found myself writing the fourth novel in a row about the same exact characters are the times when I’ve started hurting them, a not-so-subtle vote of resentment. But how to keep a series from turning into a family reunion where That Uncle makes the same joke over and over? Well, here’s half a dozen things that have worked for me.

Hurt your characters. You can try resentfully upping the stakes by doing damage to your central characters. You might even be tempted to do a Conan Doyle and kill off your protagonist (though that was a temporary demise.) But you need to remind yourself what happened to Nicholas Freeling’s Arlette Van der Valk series, which began when he killed off her policeman husband after eleven successful outings. What, you don’t remember Arlette’s series?

Exactly.

Maybe we should look at less drastic ways of keeping your readers, and yourself, eager to start a new book.

Travel your characters. I started writing a series about a girl who meets an ageing detective on the Sussex Downs. Which made for a great meet, since that was where Sherlock Holmes retired, but there’s even less scope for dastardly murder on the Downs than there is in Cabot Cove. So beginning with that first book (The Beekeeper’s Apprentice), they wandered. And in subsequent volumes they went far afield: Palestine, Lisbon, Morocco, India, Japan… Each of those places, particularly in the 1920s, had a distinct personality and a new set of problems—political, social, economic, criminal. […]

Read MorePhoto by Pat Mazzera

Yes, I know, how slight and sentimental—a story of love, while the wolf devours the world.

That sentence appears on the first page of my current novel, which I just finished. It captures not just my hero’s world view, but my own. And since it’s Valentine’s Day, it seems appropriate to talk a bit about that curious experience: love.

In the aftermath of my first wife’s death, I had to find not just a reason to live but a way to do so.

The reason came quickly enough: I wanted to live for the sake of the companionship of the people—and three wee dogs—I had come to cherish. Don’t laugh—the dogs proved crucial. (Tilly, the last of the three, is pictured above.) It wasn’t just in connection but care that I found my way. I wasn’t terribly good about caring for myself for a while, but the dogs needed me, and that kept me going even during the darkest days.

Once I decided not to jump ship, the next question rose to the fore—if I’m going to live, what matters? How can I make that guide my life?

I decided on three key virtues as my compass: love, honesty, courage. I knew, given my innate capacity for over-complication, that I should keep it simple. And I quickly learned that living up to a mere three virtues proved far more difficult than I imagined.

More importantly, I quickly discovered they were interconnected.

The word courage, of course, has its roots in the Latin word for “heart,”though the evolution of usage is never as simple as that. This, from the Online Etymology Dictionary, brings that point home:

1300, corage, “heart (as the seat of emotions),” hence “spirit, temperament, state or frame of mind,” from Old French corage “heart, innermost feelings; temper” (12c., Modern French courage), from Vulgar Latin *coraticum (source of Italian coraggio, Spanish coraje), from Latin cor “heart”…

Meaning “valor, quality of mind which enables one to meet danger and trouble without fear” is from late 14c… Words for “heart” also commonly are metaphors for inner strength.

In Middle English, the word was used broadly for “what is in one’s mind or thoughts,” hence “bravery,” but also “wrath, pride, confidence, lustiness,” or any sort of inclination, and it was used in various phrases, such as bold corage “brave heart,” careful corage “sad heart,” fre corage “free will,” wikked corage “evil heart.”

“The saddest thing in life is that the best thing in it should be courage.” —Robert Frost

Though we often think of courage as persistence in the face of fear—worse, the absence of fear, which is abnormal—this automatically begs the question: why? Why persist? Why not succumb to the fear—run, hide, compromise, surrender?

The answer typically lies in something or someone the individual values with her whole being, or feels she must defend at all costs. Something or someone cherished. Loved.

And yet how easily we fool ourselves in our affections. I’d be amazed if more than a handful of people reading this post haven’t had at least one relationship that didn’t deserve the epitaph, “What was I thinking?”

Misguided love is a kind of self-betrayal, a denial of what one […]

Read MoreEvil? by neverything

Any quasi-sentient being who’s been paying attention to recent news has encountered frequent if not exuberant usage of that uniquely evocative word, “evil.”

The assassination of Qesem Suleimani alone has brought forth the word with impressive regularity, ironically not just to describe the decedent but also those responsible for his death.

The fact the word can be employed in such diametrically opposing ways suggests more than just moral relativism or ethical facility. It points out that, irrespective of whether something we might call evil truly exists, the use of the term to describe one’s adversary will continue as long as sanctimonious self-congratulation resides in the hearts and minds of mankind.

But as writers, we should avoid such convenient simplicities. We’re in the truth business, even when we employ fiction as our method—especially then.

Those of you who attended the Un-Conference may recall my presentation on villains, specifically my attempt to define what we mean by evil in a character. This is problematic given our need to justify, not judge our characters, and to keep in mind at all times that every character is the hero of his own narrative, regardless of what repulsive, horrifying, inexcusable means he employs to pursue his ends. That effort rests on our commitment to always see our characters as human subjects, not objects.

And yet even a passing acquaintance with the affairs of mankind alerts us to the presence of those individuals who not only cause harm and damage in the pursuit of what they want, they go further. The create that harm or damage deliberately, with “malice aforethought” or “malignant hearts,” or worse—they savor the harm, delight in it.

“The cruelty is the point,” as some have remarked concerning current immigration and asylum policies.

In creating a character who fits that prototype, if we wish to be honest, requires us to dig deep and explore where that sense of cruel vindication comes from, what generates and justifies not just the need to inflict pain but the exaltation in it.

Often, a sense of weakness or victimization is being reversed, not infrequently tinged with a profound sense of shame, guilt, or both. In this sense, it is an act of psychological legerdemain, where that sense of shameful victimization or weakness gets magically erased by being transferred onto another.

This also suggests that the new victim must be selected carefully, to truly expiate the old feelings of inadequacy, otherwise the magic won’t quite work.

It’s a sneaky business, finding just the right victim who best represents what we hate about ourselves. But this is a fool’s errand, because the magic is tainted by its nature. The shame and terror can never be truly erased—it really is part of us, not them—and so a new victim, a better victim, must be found, over and over, ad infinitum

This logic applies across a wide spectrum, from schoolyard bullies to abusive husbands to sadistic cops to serial killers, even to heads of state. Ivan the Terrible, after all, didn’t earn his catchy sobriquet by being open-hearted.

Whether the term “evil” applies to Qesem Suleimani is a question I don’t intend to address here. Dexter Filkins wrote an excellent profile of the man for the New Yorker in 2013. (To read it, go […]

Read MoreBuckingham Palace Victoria Memorial by Gary Todd

Yes, I know it’s Friday the 13th, but I don’t want to talk about horror and dread. I want to talk about quite the opposite.

During the recent Unconference in Salem, Donald Maass spoke about emotional turning points in stories, and specifically mentioned how moments of forgiveness can have great dramatic power.

In my own talks, I too discussed the power of forgiveness. I believe forgiveness is a rare touch of grace in any life, given the human propensity to hold onto grudges and grievances and to fear that if we try to let bygones be bygones, we’ll only be hurt, betrayed, or taken advantage of again.

But the power of forgiveness on the page is complicated by the difficulty of conveying it convincingly. Just as you cannot make someone love you, you cannot force someone to forgive you. Love and forgiveness are gifts, not rewards.

Just as you cannot make someone love you, you cannot force someone to forgive you. Love and forgiveness are gifts, not rewards.

This means that no matter what your character does in her attempt to be forgiven, the actual act of forgiveness lies completely beyond her control. Even penance that convinces the reader that it’s time to move on may not have the same effect on the character in the story whose forgiveness is sought.

This is what makes forgiveness so powerful. It is uncommon, it is unearned, and yet when it finally appears there is something almost otherworldly about it. The great burden of guilt has been lifted, and a newfound freedom from the past is born.

A particularly moving example of how this can be done well appeared in an episode of the TV series The Crown this past season. The episode, titled “Bubbikins,” was memorable not just for how emotionally affecting it was but for how the moment of forgiveness was staged.

WARNING: spoiler alert. If you have not watched this episode and want to remain surprised when you do, stop reading now.

The episode begins in a convent in Greece with an aging nun standing in her dilapidated convent. What makes her particularly memorable, however, is that she is lighting up a cigarette, and clearly enjoying her first inhale.

The “chain-smoking nun” is an iconic example of a kind of contradiction I describe in The Art of Character as comic juxtaposition. And like all proper uses of contradiction, this one immediately fascinates—who is this woman? What makes her tick?

Shortly, we see her conversing in with her accountant over the convent’s lack of funds. A new roof is needed as well as medicine and food for the poor people the convent cares for. Reminded that in previous crises she always found some way to come up with the money, she replies that she has nothing else to sell.

This turns out to be untrue, and another contradiction presents itself. The nun goes to a bureau drawer and removes a large, stunning broach wrapped in a lace hankie. She passes through armed guards in the city streets—some kind of civil unrest is afoot—to a pawnbroker. The man refuses to believe the broach is real because he’s never seen a sapphire so large. She replies that he […]

Read MoreAmong the great joys and benefits of teaching is the opportunity to learn from my students. That point hit home dramatically this week at Uncon – or rather, at lunch just before registration began.

I happened to arrive at the Hawthorne Hotel restaurant shortly before another conference attendee, L. Deborah Sword, and upon realizing we were both there for the conference we decided to share a table.

I quickly became intrigued by Deborah’s story. A Canadian (she lives with her US-born husband in Calgary), she more than lived up to her country’s notorious reputation for sheer unadulterated niceness. I shortly learned, however, that her gentle, courteous demeanor was hard-won. She has spent much of her life researching, consulting, speaking, and writing about conflict.

She started with a master’s degree in environmental dispute resolution, then moved to conflict management, which focuses on “conflict competence.” For her doctorate, she studied conflict analysis, which seeks to ask better questions about the heart of conflict by analyzing the issues earlier and delving deeper into their nature and origins. In her “volunteer time,” she has served on the boards of directors of numerous environmental and peace organizations, and she donates her services to a number of nonprofit agencies.

She’s here at the Uncon to see if she can find a home for her first novel so she can begin her second, which she eagerly hopes to do. Its protagonist will be a woman lawyer in an alternative history featuring a speculative world in which a crucial British case concerning shareholder rights versus community interests goes differently than it did in reality. The narrower financial interests lose out in her version, and the broader impacts to society become central to the world Deborah imagines.

But the teacher’s lesson began when Deborah asked me what I was working on. I mentioned I thought I had finally managed to find the solution to a crucial section in my current WIP that had stopped me cold for months, largely because of the research required.

The section concerns a young African-American woman born as a slave within the Choctaw tribe. (The “Five Civilized Tribes”—Seminole, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Cherokee, and Creek—were all driven from their native homelands in the South along what came to be known as the Trail of Tears, due to the high death toll the tribes suffered along the way. Like the whites among whom they had lived, they too had African-American slaves, and brought them to their new homelands in Indian Territory, modern-day Oklahoma.) At the outbreak of the Civil War, the young woman’s family decides to make a break for Mexico, where slavery is outlawed. This requires a hazardous trip across Texas, in the grips of a decade-long drought. Only the young girl survives, and she is found wandering the barren grasslands by a Comanche hunting party. She is taken into the tribe, where she gradually evolves from a prisoner to a “chore wife” of a head man within the tribe.

After I recounted all this to Deborah, she mentioned that, in Canada, reconciliation with the First Nations on whose land we live is a government priority, and official public gatherings often begin with a verbal naming of the Tribal lands and treaties. She asked a simple […]

Read MorePhotograph by Anna Ty Bergman

David Corbett, here. I’m teaching at the History Writers of America Conference in Colonial Williamsburg, Virginia today, so I’m handing over this month’s post to a writer I very much admire, Hilary Davidson.

Before she became a full-time, award-winning, bestselling novelist, Hilary was a journalist, starting as an intern at Harper’s Magazine in New York then joining the staff of Canadian Living magazine in Toronto. After deciding that she’d rather write than edit, she left her day job to freelance full-time. That decision led her to write 18 nonfiction books and articles for wide array of publications.

Her debut novel, The Damage Done, won multiple awards for Best First Novel, and launched the Lily Moore series that continued with The Next One to Fall and Evil in All Its Disguises. Hilary’s first standalone thriller, Blood Always Tells, was published in 2014 and her latest novel is One Small Sacrifice, the bestselling first book in the Shadows of New York series. The next book in that series, Don’t Look Down, will be released in February 2020.

Hilary’s short stories have also won multiple awards and have appeared in a wide variety of outlets and anthologies; in 2013 she gathered some of her personal favorites for a collection called The Black Widow Club: Nine Tales of Obsession and Murder. (For more information about Hilary and her books, visit her website.)

I asked Hilary if she could provide our readers with some guidance on how to navigate the often perilous cross-currents of today’s publishing world. Turns out she had a very on-point story to tell about the need to take a leap of faith—in oneself.

SHOULD I STAY OR SHOULD I GO?

Growing up, there was nothing I loved reading more than advice columns. They were in newspapers and in magazines, and even in the tabloid papers my grandmother passed along to me. The most-asked question over the years was always some variant of, “My spouse is a good person, but we don’t see eye-to-eye on a lot of things or share the same values; I don’t know whether to stay or leave…” The usual response—unless the partner was engaging in truly terrible behavior—was that such feelings were normal and of course any sane person would stay.

Accept what you have, that was the message. Good enough is as good as it gets.

A few years ago, I found myself asking the same question, only it had nothing to do with love; it was about my career. I would be the first to admit that I’d had a fortunate start in publishing: I was represented by a well-established agent, published by a Big Five publisher, and my debut novel had won the Anthony Award for Best First Novel. Who wouldn’t be thrilled with that? But by the time I published my fourth novel, Blood Always Tells, I was looking at my career and wondering whether I needed to stay or leave.

To be clear, there are no villains in this story, and no one was doing me wrong. But […]

Read MoreThis post is about series of vicious murders, a class I conducted on how to fictionalize such horrific events, and a student who taught me something important in the process.

This all took place late last month at the Book Passage Mystery Writers Conference in Corte Madera, California. For the past several years, I and fellow faculty member George Fong—former FBI Special Agent, now security head for ESPN and a novelist himself—have conducted a class where we take a criminal case, outline the facts, and then ask the participants how they would go about fictionalizing the material. The past two years, we’ve added Jim L’Etoile to the mix, a longtime veteran of the criminal justice system (he’s the son of prison warden)—and, you guessed it, he too is a novelist.

George, given his law enforcement background, has normally led the way by presenting the case; Jim and I have then led a group discussion on how to approach what George has presented as source material for fiction, asking such questions as: Who is the protagonist? Should there be a narrator? Who should have POV status? Where should the story begin? When should the identity of the criminal(s) be revealed? How will answers to these questions fundamentally change the tone, pacing, and dramatic tension of the narrative?

In the past, George has presented cases he has personally worked on, including the Yosemite murders and a Russian mafia kidnap-extortion case out of Los Angeles.

This year, however, he decided to look beyond his own experience and instead present a headline-grabber that many of the conference participants would surely know about: the Golden State Killer case.

George reached out to Steve Kramer, an attorney who previously worked in the FBI’s Los Angeles office, who, despite not being a field agent, turned out to be instrumental in identification and apprehension of the criminal in question, Joseph Deangelo. He simply took it on himself to solve the case which, at the time he got involved, had lain dormant for years. He specifically worked closely with Contra Costa Sheriff’s Detective Paul Holes, who had responsibility for several open cases believed to be linked to the suspect then already identified by the moniker the Golden State Killer.

[Note: Though Michelle McNamara’s incredible true crime book, I’ll Be Gone in the Dark: One Woman’s Obsessive Search for the Golden Gate Killer came out not long before law enforcement identified and arrested Deangelo, it did not, as some believed, point investigators to him as a suspect. Their work, which relied largely on DNA evidence, was independent of McNamara’s.]

During our workshop, George laid out the most salient facts of the case for the participants in a Power Point presentation:

Read More

I’ve invited Zoe Quinton to join me for this month’s post. She’s not just the brilliant daughter of New York Times bestselling author Laurie R. King, she’s also Laurie’s agent and publicist. In her “spare time,” Zoe is an editor and a consultant on the publishing business, including concept development and marketing.

For this post, I wanted to focus on developmental editing, a service both Zoe and I provide. It’s distinguished from copy editing in several significant ways. Whereas the latter deals with issues such as grammar, usage, syntax, punctuation, and fact-checking, developmental editing deals with more global story issues: characterization, theme, plot, pacing, continuity, and so on.

David: Why not tell our readers a little bit about your background and how you got into developmental editing.

Zoe: Well, for me that’s a little like saying how did you get into breathing. I can’t honestly remember a time that books weren’t a large part of my life, a constant companion, a source of escape and wonder. I remember even as a child narrating the mundane events of my daily life as if they were written down in a book. I have always eaten, breathed, drank words.

I can’t honestly remember a time that books weren’t a large part of my life

It helped that my parents also both lived a life of the mind, my dad as a religious studies professor at our local university and my mom first as an academic and then as an author. I’ve been accompanying her to publishing events since I was thirteen years old, so words and reading are literally part of my blood.

I myself am a recovering academic, as I got a master’s degree in international history from the London School of Economics when I was 25. I loved the research and the—no surprise—storytelling of history, and the training I received was priceless: I learned to think and write and argue, how to shape words into a weapon or a salve, how to choose just the right fact to prove my point and let the others fall by the wayside.

A few years later, I started working as my mother’s publicist and later agent, and I soon leveraged my decades of experience by her side into a consulting business helping authors write, edit, and sell their books. My favorite part of my work is truly the editing, where I can get lost in the words and the flow of the story for hours at a time. In a way my life has come full circle—I’m still the girl with her nose stuck in a book, but now I’m getting paid for it.

David, I’d like to know what your favorite part of editing is. Do you, like me, stare into space while working on a project trying to figure out how to make that tricky plot point work? Or is it when a client really gets it and runs with your advice in just the right way?

David: Since I came to developmental editing by way of teaching, I can readily say that the best part of editing is when a client gets back to me saying they understand what I was trying to convey about their work and have launched […]

Read MoreRose Compass by Enrico Strocchi

How do our characters navigate their way through difficult choices where the moral issues are ambiguous, contradictory, or insufficient to resolve the dilemma? How are they to determine what is the right or the good thing to do? How can they be sure of what the wrong or the evil thing is to do?

This is the topic of the presentation I gave at Craftfest on Wednesday, the subsection of Thrillerfest devoted to enhancing one’s writing skills. Fellow Unboxer Donald Maass also presented, revisiting a talk I’ve heard before and which changed my entire way of looking at suspense, “Your Thriller Isn’t Thrilling.”

I’m going to begin the lecture by asking everyone to answer the following questions with respect to their current work in progress. (Note, given the crime-mystery-thriller context of the conference, the questions have a definite slant in that respect.)

Ask yourself for both your protagonist & your opponent:

With the answers to those questions in mind, consider the following scenarios:

Example #1: You work for an International Non-Government Agency (INGO) working with refugees, such as UNHCR, International Rescue Committee, Mercy Corps, etc. You have food and medical supplies for residents of a refugee camp. But the camp is controlled by an armed militia that insists that its warriors and their families get these supplies first, and they take whatever and however much they please. Therefore, if you provide the supplies, you are directly aiding a combatant and potentially contributing to the war effort, which will cost lives and increase suffering. If you don’t provide the food and supplies, people in the camp will suffer and even die. What do you do? On what basis do you make your decision?

Example #2: You are interrogating a terrorist that you believe has vital information about an upcoming attack, an attack other intelligence indicates will take place in less than 12 hours. The subject has thus far proven unwilling to say anything. You proceed with “extreme methods,” and the subject provides a location for the bomb. Officers rush to the scene but find nothing. The subject lied. As you are about to resume torturing him, word reaches you that a massive bomb placed in a delivery van has gone off in midtown Manhattan. There are hundreds of dead and injured, maybe more, and nearby buildings lie in flames. The terrorist tells you, “ I knew how long I needed to hold out, and that a lie would buy me time. Do whatever you want to me now. We won. And I am at peace with my God.” You and your fellow interrogators proceed to beat him to death as punishment for the innocent lives lost from the bomb. Whose actions are moral here? Whose are immoral? How can you determine which is which? Does this sort of extreme situation somehow lie outside of moral concern—i.e., are there other concerns rather than moral ones to be considered?

Example #3: You and your best friend are prisoners in a concentration camp. Your […]

Read MoreChernobyl by Dmytro Syvvi

This is one of those posts that begins by telling you what I intended to write, why I decided not to write that, and how it led me to what you’ll read below.

I will be in Ireland when this post goes up (meaning I won’t be available for comments—sorry), and what I wanted to write was a sort of paeon to the incredible outpouring of great Irish writing going on right now, especially in the north.

Adrian McKinty, Belfast-born and one of my favorite novelists, is currently working on a piece featuring only the new crop of northern Irish writers, and he’s finding that task alone daunting. On Twitter, he remarked: “Someone needs to do a PhD thesis on this. Civil war + peace + a generation = cultural boom?”

And that’s just the north. Even if you narrow it down to the “Celtic Dawn” in crime fiction, you quickly find yourself overwhelmed. Brian Cliff’s Irish Crime Fiction surveys the terrain masterfully, but it’s a lot of terrain.

So I found myself faced with the prospect of doing the job well, meaning a great deal more immersion than I can currently justify given other obligations, or simply refer to the writers I know or have read and admire, which would seem to give the whole topic short shrift. So I began to think I should wait, do more research, and approach the subject with the breadth and depth it deserves.

I was in the middle of this conundrum when two of the Irish writers I intended to feature in my original piece, Adrian and Steve Cavanagh (another wonderful novelist from Belfast), got into a lusty back and forth on Twitter over a critique in the New Yorker of the HBO miniseries Chernobyl.

The critique was written by Masha Gessen, a Russian emigre who has written expansively and insightfully about the Soviet Union and present-day Russia. I have to admit to being a bit of a fan, and I make a point of reading anything that crosses the virtual transom bearing her byline. So I was predisposed to take her perspective to heart.

Though giving the show credit for attention to detail, Gessen faulted it for using certain storytelling techniques, which she derided as the “outlines of a disaster movie,” to attempt to tell the truth about a situation that defies easy fictional portrayal.

The result, to her mind, often veered between “caricature and folly.” Her chief complaint was in the way the show attributed agency to individuals in a system that crushed individual initiative. She conceded that the resignation typifying Soviet life was “depressing and untelegenic,” and that the conflict necessary for a compelling fictionalization would by necessity falsify a world where “confrontation was unthinkable. But in ginning up such agency and confrontation, the show “cross[ed] the line from conjuring a fiction to creating a lie.”

“It would be harder to show a system digging its own grave instead of an ambitious, evil man causing the disaster. In the same way, it’s harder to see dozens of scientists […]

Read More“Prison” by Kim Daram

Every Thursday from 5:30 to 7:00 PM I join author Kent Zimmerman in teaching a class on writing at the California Men’s Facility (CMF) in Vacaville, California.

We cover fiction, memoir, poetry, even screenplays—whatever the men submit. Most of the manuscripts show a need for basic grammar, spelling, and syntax skills, while a few are as accomplished in style as anything I get from students outside, with stories that hands-down, in subject matter if nothing else, beat most of what I’ve seen from MFA candidates.

As Joe Loya, himself an ex-con (he served eight years in federal stir for bank robbery, and is the author of The Man Who Outgrew His Prison Cell), once remarked: Every convict has at least one great story—the story of his arrest.

The most surprising element of the writing, though, across the board?

Honesty. The men in my class have highly tuned BS meters, and have little patience for self-serving piety or glad-handing, from each other or from Kent or me. It’s made me far more aware of when I’m holding something back, or shading something to make it sound more interesting or less offensive than it really is. And that in turn has taught me to listen more carefully, and not to judge.

That lack of judgment is important. The men don’t need me to judge them. They need me to listen and help them write better, period. Funny thing, though. In the process, we’ve build a genuine bond of respect, fondness, and mutual concern.

A little background: Kent’s a long veteran of teaching in prison. He and his twin brother, Keith, taught at San Quentin for nearly a decade before submitting a grant proposal to expand their program to other prisons. Just as this effort was bearing fruit, Keith’s Scottish wife desperately wanted to return home to Glasgow, and so Kent was suddenly not only deprived of his lifelong sidekick and co-writer (working together, they’ve written a number of books on the music business, Hells Angels, the Chicago mob, and more), he lacked someone to help him teach some of these now far-flung classes, ranging geographically from Folsom to Chowchilla, 150 miles apart. Vacaville’s not far from where I live, he asked if I’d like to come aboard, and I said yes.

That was two years ago. Some of the men in the class have moved on, either through release or transfer, including a car thief nicknamed Sideshow who wrote some of the funniest, craziest, most interesting stories it’s ever been my pleasure as a teacher to read.

Several others, especially a core group of particularly strong and insightful writers, remain. At least six of them are serving sentences for murder.

What can you learn from a murderer?

Read More

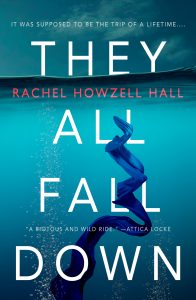

I heard of Rachel Howzell Hall long before we actually met. I had been told by friends about her Elouise “Lou” Norton novels based in South Central Los Angeles, and found them every bit as smart, grounded, and compelling as advertised. Then I read her now famous 2015 essay, “Colored and Invisible,” where she discussed being one of the few black writers at annual mystery conferences. (This was the inspiration for a six-writer roundtable in Writer’s Digest on the issue of being a writer of color in the crime genre.)

Finally, Rachel and I met face-to-face in 2017 at the Writer’s Digest Novel Writing Conference in Pasadena, and were on a panel together where her self-effacing humor, gracious charm, and [insert superlative adjective] intelligence were impossible to ignore. I got on my knees and begged her to be my friend. (Not literally, but close.)

I also began working to get her to join us at the Book Passage Mystery Writer’s Conference in northern California, where she appeared in 2018 and was so popular with the participants we’d like her to be a permanent fixture—ahem, I mean tenured faculty member—if she’ll have us.

That may be hard, because she’s going to be in high demand now. Her latest novel, They All Fall Down, a standalone thriller that came out three days ago—based loosely on Agatha Chriustie’s iconic And Then There Were None—has been getting sensational reviews (“”[A] master class in strong, first-person voice”–New York Journal of Books), and it just may be that her twenty-year slog to Overnight Success may finally have paid off.

Here–let her tell you about it.

You didn’t start out as a crime-mystery writer at all. What were your first efforts in fiction, and how did that turn out for you?

No, I didn’t start out as a crime writer, but my stories always included elements of the genre—people doing bad things to each other and someone trying to understand motives. I always wrote worlds that were ‘off,’ but back then, I didn’t know to label it as ‘crime.’

In my first published novel A Quiet Storm, there’s drama, psychological suspense and a disappearance. The question that threaded the story was, ‘What happened to Matt?’ And, of course, if I wrote that story now, it would probably have the point-of-view of the detectives who, as it stands, make relatively minor appearances in the story.

But I liked the crime and mystery part of the story the most, I just didn’t know how to pull it off while also figuring out my voice. This led to a period in my career where I couldn’t sell a thing because I liked darker material, with black characters, with my odd sense of humor. Editors didn’t like it, couldn’t figure me out. Some were offended by my humor and some didn’t think my stories were ‘urban’ enough.

Rejection became as common as pigeons to me but while I flirted with the idea of quitting, I didn’t. I let those hours of dejection and depression pass and I went back to it. In the meantime, two of my rejected novels were self-published on Amazon. While they weren’t perfect, the stories are solid […]

Read More