Posts by Dave King

From Hermes the trickster to Renaud the Fox to Sherlock in all his incarnations, readers have always loved stories of smart people being smart. It’s fun to watch an apparent weakling defeat someone stronger through sheer cleverness – David and Goliath became an archetype for a reason. It’s rewarding to finally see what the smart person has seen all along – to have the veil pulled back to see how the killer actually did it. And there’s always pleasure in simply watching someone doing something that they’re very good at.

The thing is, how do you create a character who’s plausibly smart?

This problem comes up most often in mysteries, where the detective has to be cleverer than both readers and everyone around him or her. But if you’ve ever had a story ruined for you because a main character pulled some boneheaded move at a critical juncture, you know that lack of smarts can do damage no matter what the genre.

The first step in creating smart characters is to remember that you can give your character the gift of discernment by stacking the deck in their favor. You’re in charge of your plot. You know what will happen, what will be important, what all the characters are doing. So your detective can find the key clues because you’re the one who planted them. Your heroine can avoid making stupid decisions because you know in advance what will happen to her.

The danger with this approach is that it can easily become obvious that you’re giving your detective a boost from behind the scenes. When your detective suddenly hangs the entire denouement on some insignificant slip someone made back before the murder took place, then your readers are going to be less than impressed. It’s much more effective to let your detective not simply see facts that no one else has noticed, but to see something new in facts that everyone else already knows. When Sherlock Holmes pointed out the curious incident of the dog in the night-time – the classic obvious clue — Detective Gregory knew the facts as well as he did. Gregory – and Doyle’s readers — simply didn’t understand what they meant.

You can set up this kind of double meaning because, again, you’re in charge of what happens. When you’re structuring your mystery, you can pick some key clue that has both an obvious meaning and a more subtle, second meaning. An old friend of your main suspect gives him an alibi. The alibi could be genuine, or it could be a lie, provided out of friendship. Or – as your detective might eventually realize – it also gives an alibi to the alibi witness, who turns out to be the genuine killer.

Another way to make your main character seem smart is by contrast – to give them a “stupid friend.” In a lot of classic mysteries, stupid friends were also handy for getting information across to your readers – the detective almost always explained all the clues to the stupid friend in the end. And though the stupid friend is most often a trope used in mysteries (looking at you, Captain Hastings), mainstream novels and romances often benefit by giving the main character a sidekick to bounce […]

Read MoreWhen Isaac Newton first came up with the theory of gravity, he presented what seemed like a simple problem. If you have three bodies orbiting around each another, how do you come up with an equation that describes how they move? Two hundred years or so later, mathematicians came up with the answer – you can’t. It’s easy enough to describe two bodies orbiting around one another – the Earth and the Sun, say – but once you throw in more bodies – the moon, for instance, or the other planets – then you can’t really predict what will happen. The extra bodies throw the system into chaos. This is why you’re always seeing news reports about celestial events that won’t happen again until some seemingly arbitrary time in the future.

When you’re writing a novel, you naturally center on your hero or heroine, tracking his or her fears and desires to your big climax. That’s where your story lies. With a mystery, you’ve also got to consider the perspective of a second character, the murderer. Romances, too, involve two characters whose lives circle around one another, as do thrillers that include a well-developed villain. All these stories tell how these two characters orbit one another and come together at the end.

But most stories have more than two characters, which means you’ve also got these other people with their own motives and desires circling around your main characters. How you handle these other characters – how much independence and individuality you give them – can change how much your fictional world feels like real life.

The obvious mistake — and it’s easier to make than you might imagine — is to simplify the other characters to the point where they become props. They don’t really have internal lives or backstories of their own, they’re just there to play a specific role in the story – feeding your readers critical information, or causing some complication at a critical point. Granted, you don’t have to delve deeply into the motives and history of the delivery guy or the cop who pulls the heroine over that one time. Their characters don’t have to amount to more than a couple of telling, idiosyncratic details.

But when your supporting actors – outside the orbit of your one or two main characters, but still players – are nothing more than props, your story is going to feel less authentic. After all, everyone but a complete narcissist knows that other people are living lives as unique and complicated as their own. So if your hero has a friend whose only purpose is to provide comic relief, or if your heroine has an old lover who is only there to play the rival, your readers simply aren’t going to believe in your world.

Read MoreFirst impressions count. And your title is the first impression you make on your readers. Problem is, there isn’t much to a title. In fact, they’re considered so content-free that you can’t copyright one. You could call your next book The Great Gatsby and no one could complain – legally, at least. So if you only have a handful of words to draw your readers in, how do you pick the right ones?

The most obvious step is to choose a title that gives your readers a quick glimpse of your contents. This could be the main event (Agatha Christie’s A Murder is Announced), a central character (Paula Hawkins’ The Girl on the Train), or even a key location (Frank Herbert’s Dune). So if you’re looking for a good title, the place to start would be a one or two sentence summary of your story, or a list of your main characters, or even a list of locations.

But the contents of the book are just your starting point. Look for a title that ascribes meaning on more than one level. C. J. Box’s Badlands takes place in the actual badlands of North Dakota, but the title also evokes the corruption and danger that are moving into the area with the discovery of oil. Some of the action in Hillary Mantel’s Wolf Hall takes place in the actual hall – the home of the Seymour family at the time – but the title is more about the cutthroat world of Tudor court life that Thomas Cranmer finds himself immersed in. And Andy Borowitz, one of the best humorists working at the moment, recently wrote a serious short piece called “An Unexpected Twist,” which describes both his struggle with a twisted colon and the way that a simple medical problem suddenly turned life-threatening.

Another way to capture some of the spirit of your story is through irony. The Hunger Games puts together two contrary ideas – the misery of hunger and the playfulness of games – in a way that sums up the dystopian society of the novel. Lauren Groff’s Arcadia is about a commune by that name in the sixties, with echoes of earlier incarnations of rural utopias. But the focus of the main character’s story is how he learns to see the darker realities behind the utopian ideals.

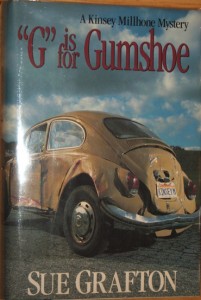

It’s often easier to find a title if you’re writing a series, since a string of similar titles helps establish your brand. Sue Grafton fans recognize her alphabet books immediately, and James Patterson is doing well with his numbered series. Even here, though, pay attention to the contents of the story. The single word that Grafton changes with every new book also manages to resonate with what’s between the covers, either directly with the content (C is for Corpse) or with the meaning of the book (L is for Lawless, which centers around a family long comfortable with breaking the law).

If you have a distinctive voice or are aiming at a unique publishing niche, giving your books similar titles can establish your brand as an author. Many of Scott Turow’s books are titled with legal terms: Burden of Proof, Presumed Innocent, Personal Injuries. Michael Crichton seems fond of punchy, single-word titles: Sphere, Timeline, Congo, […]

Read MoreA couple of months ago, a writer posted a problem on the WU Facebook page. A character who would play a major role in her plot’s climax didn’t show up until the second half of the novel. This meant they never got a chance to know the character well enough given her place in the story, which made her more of a plot device than a person. The problem was, if the author introduced her earlier, the ending would lose some of its shock value because readers would guess the character was going to figure into it somehow. Otherwise, why would she be there?

Stories are artificial, with a carefully constructed internal architecture, each piece relying on the others, all of them there for a reason. And readers are aware of that. Sure, they’re willing to suspend disbelief and enter the world of a story as if it were real life. But they’re still aware of the structure behind the story, even if they’re not conscious of it.

Normally, this isn’t a problem. If your characters are engaging enough, readers are willing to forgive you a plot whose bones show through from time to time. But the more your readers notice your plot architecture, the harder it is to suspend disbelief. The most effective stories are completely transparent, with readers blithely unaware of the author’s behind-the-scenes manipulations. How do you get your story to that level? How do you give an essentially artificial construct the organic feel of real life?

The most effective way is to watch and listen to your characters as you write. When you let your events arise out of their personalities and desires, the story they lead you into will feel more authentic. Unfortunately, I’ve seen a number of clients who became clients because their characters led their stories right into the woods – plots that rambled, doubled back, and ended up nowhere, as often happens real life. I suspect that many overly literary stories have their stereotypical flaw — engaging, beautifully drawn characters to whom nothing much happens – because the writers want to capture real life and avoid the gauche artificiality of an actual plot.

But if you want to tell an effective story with your characters, or if you still haven’t developed the depth of imagination you need to follow your characters wherever they go, then how do you get a plot that moves along so naturally that readers feel they’re watching real life unfold?

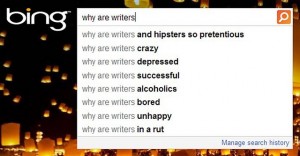

Read MorePart of my job description as an editor is to keep writers from getting discouraged as they struggle to publish and publish well. It’s not easy, since it takes a lot of effort to learn the craft of writing, and once you break into print, your readership tends to build slowly. Even writers who are prepared for these natural roadblocks often give up – I can think of several clients with promising first novels who I wish were still writing.

Maybe the answer is to change the focus, from writing to publish to just writing.

Of course, you want to publish. You want to share the joy of your creation with other people. It’s nice to have the marketplace affirm your skills. And it would be even nicer to be paid for writing, if only because it gives you more time to do it.

But if all you’re interested in is making money, there are easier ways to do it. I once had a potential client who said he didn’t want to spend money on having his book edited unless I could guarantee it would earn $100,000. I don’t think I need to explain to Writer Unboxed readers why we parted ways. So don’t lose sight of the other reasons for writing.

Read MoreBack in the nineties, before social networking or even blogs had been invented, I belonged to a chat list for published writers. You carried on a slow conversation with like-minded people by sending e-mails to a central server, which then sent them out to all members of the list. Tom Clancy, another list member, used to give a piece of advice to writers who were stuck at various stages of the writing process: “Just write the damned book.”

I think of that advice whenever potential clients ask me to read over the first few chapters of their work in progress, to make sure they’re “on the right track.” They don’t seem to realize that there is no track. When you write your first draft, you lay the tracks as you go. As you follow your story, you may find out that a minor character moves to the center of the action, or that a plot twist you’ve been building toward for a hundred pages just won’t work. Or your story may simply transform into something else as you write it. In its original draft, William Golding’s Lord of the Flies was magical realism, with Simon having genuine mystical visions and sacrificing himself willingly at the end.

The process is a little different if you work from a detailed outline, but not much. True, you do have an idea of where you’re going when you actually begin writing. But some of the creativity and surprise – the getting to know the story and characters – that other writers experience with the first draft, you get with the outline. And no matter how detailed your outline might be, you should still treat it more as a guide than a rulebook. The actual process of getting the story down on paper has a unique intimacy and particularity. Stories are organic. You’ve got to let them grow as you write, even if you’ve already built a trellis.

Still, the problem those clients are looking to me to solve is real — a lot of writers get lost in the middle of their first draft. One reason may be a lack of confidence and drive. I find it’s usually second novels that I’m asked to keep on track. Many writers enter the field because they’re burning to tell a particular story. But after the first novel is done and they launch into the second one, they often lack the passion for the story that got them through the first novel. After The Joy Luck Club, Amy Tan began and abandoned seven different second novels — at one point breaking out in hives — before writing The Kitchen God’s Wife.

You can also trip up on your first draft by focusing on the mechanics of writing – like the beginning writer who recently complained on the Writer Unboxed Facebook site that, whenever she read a how-to-write book, she felt like she was going about it wrong. It’s easy to get so obsessed with the technical details – how you’re managing your micro-tension, if you’re giving your readers enough physical description to imagine the scene, whether your antagonist is sufficiently balanced or your dialogue is pithy enough – that you can’t find your story. You’re like the centipede who was […]

Read MoreAs so often happens, the comments on last month’s piece (What Do Your Readers Know and When Do They Know It) showed that there was a lot more to the topic than I could cover in a single column. So I thought it would help to look in some detail at how a master of the craft created tension by how he fed his readers information.

If you’re not already familiar with John le Carré’s The Spy Who Came in From the Cold, the quickest, easiest way to get to know the story is to stream the movie. The plot follows the book very closely. Besides, Richard Burton and Claire Bloom are always a pleasure to watch, and keep an eye peeled for a very young Robert Hardy. If you’d like to check it out now, I’ll wait.

So, The Spy Who Came in From the Cold opens with Alec Leamas, the head of the Berlin bureau of MI6 (i.e. the Circus), waiting for Karl, his last remaining operative, to make a desperate run across the border from East Germany. Karl finally appears but is gunned down before he can reach safety. All of Leamas’ other operatives have also been hunted down and eliminated by Mundt, a particularly vicious chief of the East German secret service (i.e. the Abteilung). So when Lemmas’ boss, Control, offers him a chance to destroy Mundt once and for all, he jumps at it.

Given that setup, le Carré then proceeds to feed his readers information at three different levels of reality: what the world thinks is happening, what Leamas thinks is happening, and what is actually happening.

We first watch level one develop as Leamas comes apart at the seams. He’s given a makework job in accounting at the Circus, starts to drink, is accused of embezzlement and fired, drinks more, and winds up in a grimy apartment working a menial job at a library. There he meets and starts to fall for a young, idealistic communist named Liz (‘Nan’ in the movie). Despite the light she brings into his life, he continues to spiral downward until he assaults a grocer and is jailed. When he’s released from prison, he’s approached by a bumbling East German agent, who has heard about his situation from Liz.

At this point, le Carré pulls back the curtain on the second level. Leamas sneaks off for a secret meeting with Control that makes it clear his disgrace and collapse are a ruse to get the East Germans to recruit him. In this meeting, Control challenges him on his relationship with Liz – it’s out of character for someone spiraling into degradation to fall in love – and offers to help her out. It’s during this meeting that readers also learn, almost in passing, that George Smiley, the Circus’s legendary strategist, wants nothing to do with the operation (a detail omitted from the movie).

Le Carré still hasn’t revealed how Leamas’ staged collapse will lead to his getting revenge on Mundt, so curiosity about the plan will keep readers turning the pages. But they’ve also come to realize by this point that Leamas is intelligent, brave, idealistic, and loving. They care about him, and […]

Read MoreAs any good operative can tell you, information is power. Whether you’re dropping bombshells on your readers, teasing them with hints and suggestions, or letting them know ahead of time that disaster is approaching, you control their reactions by how and when you dole out the facts. So how do you best wield the power of information? What do you tell your readers, and when, and why?

It depends on whether you’re getting your tension primarily from your plot or your characters. If you’re naturally drawn to creating tension from events – if you love building a story around plot twists that shock your readers – then you want to hold things back until the big moment. But this is trickier than it sounds.

For one thing, unless you’re deliberately using an unreliable narrator, none of your viewpoint characters can know the key facts before you spring your plot twist. There was a time when the narrators of mysteries could tease readers with hidden knowledge. In The Door (1930) Mary Roberts Reinhart’s narrator regularly says things like, “It was then on Sunday afternoon that there occurred another of those apparently small matters on which later such grave events were to depend.” Today that approach to building tension seems unbearably quaint (as does her sentence construction).

But if your viewpoint characters are aware of the pertinent facts and you don’t reveal them, your readers are going to feel cheated. After all, if your readers are inside the heads of characters who know stuff, why didn’t they learn it as well?

Read More

“The robber baron’s cruelty may sometimes sleep, his cupidity may at some point be satiated; but those who torment us for our own good will torment us without end for they do so with the approval of their own conscience.” C. S. Lewis.

Fanatics make terrific villains, whether it’s an animal activist destroying labs where lifesaving drugs are developed, the mother who ruins her children’s lives in order to save their souls, or a terrorist blowing up civilians to trigger the holy war. Because fanatics are obsessed with a single idea, they’re impossible to reason with. They’ll cling to their idea regardless of evidence or argument. They’re often blind to the damage they cause as well, continuing to destroy the lives around them with impunity because, as Lewis says, their hearts are pure.

Yet this sincerity makes them easy to humanize. Psychopaths, by contrast, don’t feel that the people they hurt are really people, which makes them less than human themselves. It can be frightening to watch a character fall into the hands of a serial killer, say, but in some ways it’s no more emotionally engaging than if the character is attacked by a wolf.

Fanatics, though, are generally working for what they see as the greater good. And the ends they’re fighting for aren’t necessarily bad things. Animal testing is often cruel. Everyone wants the best for their children. And as John LeCarre proved in The Little Drummer Girl, readers can even be brought to understand a terrorist’s aims.

Giving your readers a sympathetic heavy draws them more firmly into your story. Both sides of your conflict become human. And while readers may still want your main character to win, they’ll feel pity for your villain, giving the conflict a new emotional level. Javert, who dogs Jean Valjean out of a fanatical devotion to the rule of law, is in the end more tragic than evil. Readers feel sorry for him when he throws himself into the Seine.

But Fanatics are easy to get wrong.

Read MoreA client recently asked me why English is so bizarre. She was trying to explain its quirks to a precocious, bi-lingual eight-year-old, and not doing very well. Not that I did much better – English is a genuinely freaky language, with random spelling rules, no particular sentence structure, and far more words than any reasonable language needs. Part of the reason it’s so confused is that it’s perfectly happy to steal useful words from just about anywhere it can get them, from Hindi (“shampoo”) to Tshiluba, one of the languages of the Congo (“chimpanzee”).

But the root of English strangeness comes from the way it was formed when two sources of language flowed together. Old English originally grew out of Anglo-Saxon, which is more-or-less Germanic. Then Old English was conquered literally and figuratively by Norman French, which was still fairly close to Latin at the time. As a result (outcome), English at its heart (essentially) has at least two words (expressions) for every concept (thought), one from each of its two mother streams (foundations) of language.

But while this hot mess of a history makes English hard to use, it does give writers a chance to control how their work feels just by picking which source they draw their language from. Short, consonant-packed words grounded in Anglo-Saxon have strength and punch, while longer, vowel-infused Latinate derivatives feel more cerebral and anemic. There’s a reason all of the most effective obscenities come from Old English. Calling someone a coprophagous, copulating, progeny of a female canine just lacks . . . spunk.

Read MoreWhich is more important, plot or character? It’s one of life’s great dichotomies, like the question of nature vs. nurture or Coke vs. Pepsi. And like most great dichotomies, the answer is: all of the above.

So it didn’t surprise me when last month’s column on Joss Whedon’s gifts with plot triggered a discussion that quickly strayed over into his gifts with character. I thought the question deserved its own column.

To recap for those of you unfamiliar with the Buffyverse, Buffy Summers is the Slayer – a young woman chosen to fight against vampires and other creatures that go bump in the night. The slayer is given enhanced strength and agility and is supported and mentored by the Watchers Council. In addition, Buffy gathers a group of friends and allies around her, not all of whom are human, who call themselves the Scooby Gang. Like much in the Buffyverse, the characters in the Gang are sometimes a little over the top. Yet they remain coherent, always interesting, and often beloved. If you’ve never seen the series, you have a treat ahead of you. But if you want to avoid spoilers, I’d stop reading this article now.

One thing that makes Whedon’s characters so memorable is that he doesn’t shy away from moral ambiguity. Even his darkest characters have balancing characteristics that make them interesting and often redeemable – the Scooby Gang has included at times two vampires and a demon. D’Hoffryn, for instance, though a Lower Being and Lord of the Vengeance Demons, is always unfailingly polite. Once, on being summoned by Willow (one of the Scooby Gang who is a powerful witch), he greets her with, “Behold D’Hoffryn! Lord of Arashmaharr, he that turns the air to blood and rains death upon – Miss Rosenberg, how lovely to see you again.”

Read MoreA couple of weeks ago, a client told me one of his beta readers had said his book read like a comic book. I asked why that was a bad thing.

Granted, you don’t want your characters to be shallow caricatures or your plot to be mechanical or contrived, which is what many people mean by “reads like a comic book.” But all of this client’s characters were fully rounded and plausibly human. Even the psychopath who hunted people down in the woods had his vulnerable moments. And while his plot had problems, contrivance wasn’t one of them. I suspect his beta reader was complaining about the fact that his manuscript was an exciting adventure story.

Years ago, I stopped reading New Yorker fiction because I lost patience with beautifully written stories in which nothing much happens. For the sake of this article (oh, the sacrifices I make.), I picked up a recent issue to try again.

Joseph O’Neill’s “The Referees” tells the story of Rob, who has just returned to New York and is trying to get two character references so he can move into a co-op. We meet a lot of Rob’s former friends and get a good idea of who he is and what kind of life he’s led. He has a clear and engaging voice, and it’s hard not to like him despite his drawbacks. The story makes good use of some advanced techniques, like present-tense narration and a highly unreliable narrator. It also says some intriguing things about how we judge one another and ourselves. But by the end of the story Rob still has only one reference, which he wrote himself, and we don’t know if he gets the apartment or not. Maybe he’s changed by the experience. Maybe he’s not.

In short, nothing happens. It does it quite beautifully, but . . .

I understand why some people might love quality characterization and beautiful writing so much that they’re willing to read a story for these pleasures alone. But most readers need something more to keep them going. They want to hope that something good – or fear that something bad – will happen to characters they care about. They want to watch those characters take action to change their fates. They want to be surprised.

They want plot.

This hunger for plot is, I think, one reason comics and YA fiction, and the movies based on them, are so popular. The best practitioners of these arts know and value the power of story, and one of the best of these is Joss Whedon. He’s the force behind the current revival of the Marvel Universe (The Avengers, the Agents of Shield), but the work I know him for best is the television series Buffy the Vampire Slayer.

Read MoreA lot of humorous novels build the comedy into the characters. We watch two hapless lovers stumble toward each other in rom-coms or pull themselves out of increasingly bizarre situations in screwballs. You can write this kind of humor with nothing more than insight into human nature and enough love for your characters to laugh at them. But you need a different set of skills to create a book where the comedy is built into your fictional world, whether it’s the alternate aristocracy of Jeeves and Wooster or the physics-bending fantasy of Terry Pratchett’s Diskworld.

A funny world has to be consistent, for instance. Not in terms of its physics or metaphysics – in fact, the bafflegab can be less plausible in parody worlds. But place you create has to have a consistent comedic sense. A cosmos in which spaceships travel by creating random whales in low earth orbit feels like the same sort of cosmos in which the answer to the great question of life, the universe, and everything is 42.

Some time ago I edited a book set in an alternate universe in which some fictional characters in our world – Sherlock Holmes, Romeo and Juliet, James Bond – had actually lived. Some, but not all – Romeo and Juliet were real, but Hamlet was not. In fact, it quickly becomes clear that fictional characters are only real in the alternate universe when it lets the writer get away with a gag. The gags weren’t bad, but the ad hoc nature of the world made it harder to believe in, and thus harder to enjoy.

One way to keep your world consistent is to think of it as just another character, with its own sensibility and voice.

Read MoreThis delightful word was originally coined in the fifties to describe deliberately confusing bureaucratic jargon. Since then, science fiction writers have co-opted the term for the scientific background you feed your readers to explain the ways in which your world differs from reality. It’s the bafflegab that persuades your readers to suspend disbelief.

It’s most often used in science fiction, of course, but other genres use bafflegab as well. Fantasy novels require a magic that behaves according to rules – what might be called metaphysical bafflegab. Some romance novels now require an explanation of where vampires come from and how they live. Even historical novels rely on something similar. People who lived in the middle ages would probably find the world of many medieval mysteries unfamiliar, if only for the shortage of lice. But that’s not a problem as long as the world is convincing enough to satisfy modern readers. After all, in Julius Caesar, Shakespeare had Cassius say, “The clock hath stricken three,” twelve centuries before the mechanical clock was invented.

How much bafflegab you need depends on your audience. The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy needed much less in the way of explanation than, say, Jennifer Wells’ Fluency. Being lighthearted lets Douglas Adams deal with alien languages by having his characters stick a small fish in their ear rather than bringing in a linguistic expert, as Wells does. If your readers are into your romance for the dark, dangerous love interests, you don’t really have to go into detail on the biology or ecology of your vampires.

Bear in mind, too, that you can often cut down on the bafflegab by using IJD technology. (How does the spaceship travel faster than light? It Just Does.) We don’t think about the details of internal combustion engines when we’re driving to work. In fact, I’m told most people never think about the details of internal combustion engines at all, though I have trouble believing that. In the same way, people in the future won’t think about how the warp drive works every time they fire it up. So a lot of your background technology can simply remain in the background.

Read More