Posts by Dave King

If you believe mystery writers, an awful lot of murders take place in isolated country cottages or on ships at sea or on snowed-in trains. This kind of isolation makes it harder for the killer to escape, but it limits the cast, which makes the writer’s job easier. It limits the number of suspects, and readers know everyone from the beginning. Some more of them may turn up dead before the end, and one or two may turn out to be long-lost heirs or imposters. But the dramatis personae is stable from the beginning.

What do you do if your cast is less well behaved, though, given to popping in and out of the narrative in unpredictable ways? Maybe your plot structure leaves you no choice but to introduce a character early on and then sideline them or bring in a new character late in the game. Your readers naturally expect that your cast of characters is stable – that they know who the important players are as they read through the story. If you drop a memorable character halfway through, readers are going to subconsciously expect him or her to show up again before the end. If you introduce a new key character near the end, readers are going to feel cheated. Part of the joy of reading is anticipating what’s coming next, and readers get upset when you hand them something they couldn’t have seen coming.

I’m currently editing a story that, near the beginning, introduces a sharply-drawn character – the main character’s boss – who has an intriguing relationship with her. The boss later plays a key role in the main character’s life. The problem is, as the writer got deeper into the story, it grew to the point that it needed to be broken into three books, and the memorable boss we met at the beginning of book one doesn’t reappear until book two.

My client can’t just cut the character. She’s going to need him eventually, and readers need to know how the boss gets along with the main character before she undergoes some serious changes in that first book. The most straightforward solution would be to create some independent subplot involving the boss that my client could cut to from time to time as the story progresses, just to remind readers he’s still there.

Read MoreSix months into the worst pandemic in a century, we’ve passed five million cases with more than 170,000 dead, more than 30 million out of work, and the economy collapsing faster than it did during the great depression. Our politics have grown even more divisive, making it harder for us to act together. The world is changing around us in ways that we can’t possibly understand because we’re right in the middle of it.

So let’s talk about how this affects your current work in progress. That is, assuming you’re actually working on your novel instead of binge watching or binge baking or binge eating or binge drinking or crying quietly into your pillow every night. Or all of the above.

Of course, if you’re just starting out on a new manuscript, the virus offers all sorts of opportunities for drama. Covid is the ultimate A Stranger Comes to Town, upending peoples’ lives, putting them under strain, and revealing their true character – think Shane in virus form. But there’s something you’ve got to watch out for if you do decide to work Covid into your story — we still don’t know how the pandemic is going to end. Stuff could easily happen in coming months that will eclipse anything you might use as a background now, leaving your story feeling dated before it’s even finished.

Read MoreIf you read writing books, you know that your characters should say whatever they say, with no help from you. “John said” or “Mary said.” Neither spluttered, murmured, extemporized, or expostulated. And no one ever said anything with an adverb attached – apologetically, artfully, dolefully, anything. In early to mid-20th century books, even successful authors just added “-ly” to any adjective, however unlikely — I’ve seen “boringly” and “heart-warmingly.” I think that habit is what killed the questionable art of adverbial speaker attribution.

It’s easy enough to know who is speaking when you only have two or three characters in a conversation. In fact, with two, you don’t have to do anything except let them talk – your readers can just follow the back and forth. But what do you do if you have a crowd to manage – a dinner party or the denouement of a complicated mystery?

The first step in keeping a chatty crowd under control is to know all the different ways you can flag the speaker of a line of dialogue. Speaker attributions, of course. “’We’ve got some old friends coming over tonight,’ Mary said.” But if you start ending every paragraph with a “said,” your readers are going to start tripping over them.

Injecting a little bit of action before a line of dialogue can flag a speaker. “Sky held out a hand with dirty fingernails. ‘Hey, dude, it’s been, like forever.’” You can also use a little interior monologue from your viewpoint character. “John could not for the life of him understand why Mary had invited Sky and Lotus Petal. They hadn’t seen them in years. But he may as well make the most of it. ‘It has. Good to see you again.’”

Read MoreSay that you’ve created a main character or two that you love and then start to follow their story. That story leads you to new characters you love every bit as much, and you delight in watching them start to interact with the main characters. Then the story takes an unexpected turn that you can’t resist, leading into new settings and new drama that absolutely excite you.

And then you realize you haven’t written anything about your main character for sixty pages, and your story is now focused on a character your readers didn’t meet until 100 pages in. So you try to pull it all together into a single storyline, and the only way to do that is through some serious deus ex machina manipulation. Then you realize that following your story has led you right off into the middle of the woods.

If you look around and find yourself lost, how do you find the breadcrumbs to lead you back out?

The first step is understanding how you got there. Every writer approaches their novel differently, and there’s no such thing as a wrong approach. But if you are the kind of writer who prefers to launch into a story with no idea how it will end, then getting lost in the woods is an occupational hazard. I know because I’ve had several clients come to me to help them find their way home.

Read MoreFor the first time, you’ve been caught up in a plot, or a character, or a world of your own making. You give in to it, give our heart to it, maybe you even start dreaming your next scenes. You find yourself dwelling on it when you should be thinking about other things. You work on it for maybe a year or more. You revise it, get friends and family to give you feedback, and revise it again. Then it’s finished, and it breaks your heart because it’s like saying goodbye to your characters.

And then you send your novel off to the professionals, either agents or editors. And learn that you should just put it in a drawer. I have had to gently break this news to clients from time to time. I feel like the police must feel when they tell someone that a loved one has died.

The problem is that novels are huge. They involve moving parts you may not even be aware of and require skills with language and tension building and insight into characters that take years to develop. You don’t just have to master these skills, you also have to develop a feel for how they all work together. And you can’t start doing any of that without investing a large chunk of your life and soul in a novel that is likely to wind up in a drawer.

I know how discouraging this sounds. I know how discouraging it actually is. A lot of writers, faced with the prospect of starting a second novel after shoving their first one in a drawer, simply can’t do it. So they give up writing and take up macramé or bowling or something. That is often a shame, because some of the practice novels I’ve seen show genuine promise. The novel itself may be so fundamentally flawed that it probably won’t ever see print, but there is clearly a real writer at work behind it, one who deserves encouragement. So take heart. The practice novel is almost always the first step that anyone takes in becoming a writer.

Remember, your writing life is about more than just this one novel, even though it’s easy to get the two confused. After all the work you’ve sunk into it, this one, massive project can become the only thing you see. But if you really intend to become a writer, you’re probably going to write a lot of different novels in your life. That will still be true, even if your first one goes into a drawer. Letting go of that practice novel is often the first step in becoming a writer.

Read MoreWhen I first started reading books more complex than Green Eggs and Ham, I fell in love with series novels. I raced through the school library’s collection of The Hardy Boys and Nancy Drew. A friend loaned me the complete John Carter of Mars series – great fun when you’re twelve, though they don’t hold up very well – and another introduced me to the Chronicles of Narnia. I even went through my sisters’ old Bobbsey Twins books, which can be taken as a sign of how little reading material we had in the house.

What drew me to series was the comfort of going back to a familiar world, one that was already alive in my imagination. I looked forward to spending time with characters I’d already come to know and love. Besides, even if you’re a voracious reader, it’s a commitment to read an entire novel, especially if you can’t bring yourself to abandon a book you’ve already started. (I’ve mentioned before — it’s down in the comments — that I regret not being able to give up on Kurt Vonnegut’s Breakfast of Champions.) It was easier to commit to the next book in the series because I knew what I was getting into.

Now that I’m a grown-up editor, I can see why series also appeal to writers. It’s tough to write any novel without falling in love with your characters, and once these people are alive in your imagination, you want to keep following their stories. Besides, you can’t always really explore your characters in the space of one novel. There’s also the practical fact that agents and acquisitions editors like the way series novels offer upside protection. If your first novel hits big, your editor knows you have others in the pipeline.

But series books raise some questions that standalone novels don’t. For instance, how do you keep your characters consistent as they age? It’s part of J. K. Rowling’s genius that Harry and the Hogworts gang age plausibly throughout the series. As they mature, their relationships grow more complex, their internal struggles are more gripping, and readers are drawn deeper into the series.

But this kind of growth isn’t always possible, which is why some writers to simply freeze their characters in time.

Read MoreTwo months ago, in the article on expanding your world beyond the confines of your story, a commenter asked how much backstory she should include. I pointed out that your readers will assume that the history you’re giving them will play some role in the plot. The questioner had never thought about the link between backstory and readers’ expectations before. Now she is a little more aware of the web of connections between different parts of her writing.

I’ve written about this web in passing, while talking about genre, but it’s critical enough that it deserves a column of its own. Quite simply, you cannot write well if you’re not aware of how every aspect of your writing affects every other aspect of your writing.

This awareness doesn’t develop overnight. Most writers get into writing because they fall in love with one particular element of storytelling – getting to know an intriguing character, the joy of creating dialogue, the thrill of the slow ramp up to the denouement. When you start out, you aren’t yet aware of all the different moving parts that make up a novel – how you need to use beats to anchor characters in a physical location, say, or make sure each character’s dialogue has a distinctive vocabulary and cadence.

Even when you start to learn these things – reading books of writing advice or columns like this one – it’s easy to overlook the connections between the various bits of your writing. Those of us who write about writing tend to delve deep into one aspect of writing at a time. If you read enough advice like this, you couldn’t be blamed for thinking a novel is made up of discrete parts that you can just fasten together, tab A into slot B. If what you’re learning is something you’ve never thought of before, it’s easy to get so excited about it that it becomes the solution to all of your writing problems. When all you’ve got is microtension, everything looks like a scene that drags.

Read MoreWithin the last week, I’ve had two clients with the same problem, a sign that I’ve found a good topic for an article. (They’ve given me permission to use them as examples – thanks, guys.) What was tripping them up was that they both had to keep the focus on a key character when there was no easy way to put that character on stage.

One of the manuscripts is a historical novel set in the early 14th century and centered on two women. One is Margaret, a noblewoman who’s left in charge of her husband’s castle when he rebels against King Edward II. The other is Edward’s queen, Isabella. For reasons I can’t get into now, the castle is besieged by Edward, and Margaret is captured and sent to the Tower of London with her children. Isabella is put in charge of her captivity. For much of the book, we watch Margaret struggle to keep herself and her children sane and to gain her freedom, with few glimpses of Isabella. But late in the story, Edward summons Isabella north, then essentially abandons her. She is nearly captured by Robert the Bruce, almost dies while escaping, and finds that Margaret’s capture was part of a scheme Edward was running behind her back.

The natural structure of the story is the parallel between the two women, who start off with a serious imbalance of power and eventually grow to see that both are under the control of narcissistic husbands with little leeway to determine their own fates. The problem is that, when Margaret is in the Tower, there is little reason to include scenes from Isabella’s point of view, and when Isabella leaves London, Margaret can do little in the Tower except wait for her to return. Readers don’t really have a feeling for who Isabella is before she leaves, and they lose track of Margaret when caught up in Isabella’s adventures. (Incidentally, after the events of the story, the real-life Isabella has Edward assassinated.)

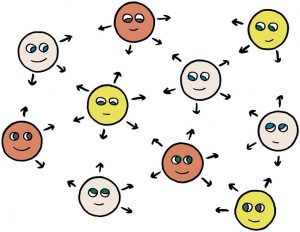

Read MoreA commercial airline pilot recently described how his job gave him a sense of how large the world really is. He would leave his home in London and drive to the airport among hundreds of other motorists and pedestrians going about their daily business. At the end of the day, he would land in New York or Johannesburg or Ankara and drive to the hotel among hundreds more. Eventually, watching these people pass by and imagining their lives made him aware that the people he’d seen that morning in London were still going about their daily business, just like the people at his destinations. This simple imaginative exercise left him with a sense that the entire planet was full of individuals living out their daily lives.

It’s natural to see the world only in terms of the people you encounter every day. We all know theoretically that there are seven and a half billion more of us out there, going to school in Lagos or heading to work in Asuncion or shopping for groceries in Osaka. We’re just not aware of them. We don’t feel they’re out there the way the pilot did.

It’s also natural to see your characters only in terms of the events of your story, giving them enough background to convey their personalities, making minor characters distinctive enough to be remembered. But you can give your story more depth – make your imaginative world bigger – if you learn to pay attention to the lives that your other characters, especially minor characters, live when they’re offstage.

When you create a minor character, think about who they are when your readers aren’t watching them. What do they do for a living? What are their good and bad habits? Married? Kids? What were they doing just before they entered the scene? What will they keep doing after they exit, stage right? If you can give your readers hints of life taking place beyond the confines of your story, you’ll make your fictional world feel not only larger, but less artificial and more authentic.

I’m currently working on a mystery in which the detective, in trying to get a sense of who the main suspect is, interviews the couple who lives next door to her. This couple only appears once in the book, for a handful of pages, but in that time readers see them arguing over who the suspect was. There’s no real anger or animosity in the argument. They still love and respect one another. They just have different ways of looking at the world and are comfortable expressing them. It’s clear this argument has, in various forms, been going on for years and will continue for years to come – it’s woven into their marriage. This glimpse of their life together stretching on past that one scene makes the couple feel more real, and the writer’s world feel larger.

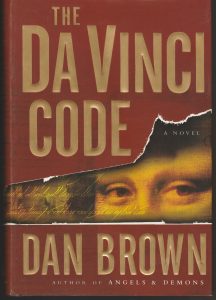

Read MoreDan Brown has mastered the art of writing books that are hard to put down. This is remarkable because, in the course of most of his novels, he also introduces a wealth of background information. Just The da Vinci Code alone – to take his most popular example – educated readers on everything from Gnostic pseudo-Gospels to Renaissance cryptography. Yet his story keeps driving forward at a fast pace that never feels forced. One of the ways he does it is by creating effective scene endings.

Of course, your denouement needs to be clearly defined, wrapping up the plot questions you introduced near the beginning and giving readers a satisfying sense of closure. Your chapter endings need to be sharp, teasing future events to keep readers from closing the book at a convenient stopping point.

Scene endings are trickier to manage simply because there are so many of them. If you work too hard to bring a cliffhanger or sudden revelation to every scene, it won’t be long before your readers feel manipulated. You want endings that are subtle enough to feel organic, but still make readers want to keep binging your scenes like a Neflix series. So how does Brown do it?

Warning: there will be spoilers. I’ll be describing the content of key scenes so even those of you who haven’t read The da Vinci Code will be able to follow what’s going on. An additional warning: I’m well aware of Brown’s other literary shortcomings. He tells a ripping good tale, but as I read through it again for this article, I often itched to pick up my editing pencil.

So . . . the obvious candidate for a good scene ending is some new revelation that leads you to keep reading to find out what it means. And Brown does a fair amount of this – the second scene of chapter 86, where Remy, Leigh Teabing’s servant, reveals that he’s secretly working for the mysterious Teacher by turning a gun on Teabing. Or the end of chapter 98, where we discover that Teabing is, in fact, the Teacher and the earlier attack was staged.

But as I say, you can only include so many of these kinds of revelations. Brown often changes things up by ending a scene, not with new information, but with a revelation that rewrites what you think you already know.

Take, for instance, the opening scenes of chapter eight. Robert Langdon, an expert on symbolism, has just been brought in on the murder of Jacques Saunier, a curator at the Louvre, who wrote a series of cryptic and possibly satanic symbols next to his body while he was dying. Most of the first scene is spent on what the symbolism might mean, with the devout Captain Fache, the police inspector who summoned Langdon, acting hostile and suspicious toward the symbols’ satanic implications. Finally Langdon makes an obvious point that, if Saunier wanted to lead police to who killed him, he would have simply written down a name.

“As Langdon spoke those words, a smug smile crossed Fache’s lips for the first time that night. ‘Precisement,’ Fache said. ‘Precisement.’” And . . . scene.

Read MoreLisbon, PT

In a recent interview for a writing blog, I was asked how publishing has changed since I’ve been an editor. The obvious answer is the rise of self-publishing and e-publishing. But these are only symptoms of something deeper.

Most publishing houses used to offer more support for midlist writers – writers who weren’t celebrities but who sold well enough to turn a decent profit. (They were “midlist” because they appeared in the middle of the list of new releases the publishing houses put out twice a year.) Then, starting in the 70s and 80s, publishing houses began to consolidate, and their approach to the business began to change. Major houses started paying large advances for established writers, looking for blockbuster-sized sales and profits. Spend a million dollars to buy the rights, spend another million promoting the book, and make five million in sales.

It’s not a bad business model, but it does limit one of the main avenues for talented new writers to break into print. Most writers will never become bestsellers, and certainly none of them start out that way. So how do the skilled, respectable writers who aren’t blockbusters get into print now that traditional publishers are a little further out of reach?

I’ve written before about small presses and self-publishing, both of which have their advantages and pitfalls. But one of the main dangers of either of these came home to me in this last month – they don’t have gatekeepers.

In order to get onto a publishing house list at all, you have to get past an acquisitions editor – the gatekeeper who both warned writers that their books weren’t ready for print and helped shape those who were close. As a result, even beginning writers had a trained professional watching over them to let them know if and when they had gone off the rails. There were still hacks, of course, but many writers who were only modestly popular in their day were skillful and engaging to read.

Of course, there are still strong, midlist writers like that today. But . . .

Read MoreNot long ago, a friend who has been reading literary novels for years recommended one to me – Norwegian Wood by Haruki Murakami – and gave me the Kindle version. Murakami is award-winning and well-reviewed, so I launched into the book with considerable hope.

I immediately met a protagonist who didn’t care much about his own life and whose memories were dominated by a love affair with a woman who barely registered as a character. I got thirty pages into it before I decided I didn’t care enough about either of them to keep reading.

I should have known better. Years ago, before the advent of Kindle, I brought home a few promising-looking books from the library for Ruth, a voracious reader. Ruth glanced through them and rejected one out of hand. “It’s won awards,” she said.

I’ve written before about my frustration with modern literary stories where nothing happens – stories that are beautifully, skillfully written, but ultimately pointless. But there’s more going on in Murakami’s book than artful stagnation — I’ve read the summary of the plot on Norwegian Wood’s Wikipedia page, and it confirmed my decision to abandon the book. His characters are in a desperate search for meaning while being driven by forces beyond their control through an uncaring world. It’s a dark vision of what it means to be human.

Murakami is not the only one who shares this vision. I got about halfway through Cormack McCarthy’s All the Pretty Horses, another recommendation from a literary friend, before I realized that I didn’t care enough about Grady’s increasingly painful and meaningless life to wade through the unconventional punctuation. My interest in English history was the only thing that got me to the end of Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall, where I watched another honorable man slowly flattened by forces beyond his control.

The problem may be getting worse. Back in the eighties, I read and enjoyed E. L. Doctorow’s Billy Bathgate. It was a beautifully-written and fast-paced coming of age story, with an engaging protagonist and an intriguing supporting cast. A couple years ago, I tried Doctorow’s more recent Andrew’s Brain, and while I found parts of it technically interesting, I was once again faced with a character about whom I didn’t care very much, a story that required considerable effort to follow, and an ending where the protagonist is simply ground down by life.

Why are so many gifted writers drawn to the dark side of life? Why are they driven to present characters who are hard to love or lovable characters in situations that are either hard to follow or hard to endure? Why does it feel like work to read them? And why are they winning awards for this?

Read MoreLots of writing books, including Self-Editing for Fiction Writers, will tell you that you can use your paragraphing to emphasize key points. Want something to stand out? Put it in its own paragraph.

Picking which parts of your narrative you want to emphasize is trickier. As a rule of thumb, it’s a good idea to highlight the moments when your scene takes a sudden turn – when your viewpoint character suddenly realizes something, or another character does something surprising, or the mood of the scene simply changes. Just let less important moments develop within a single paragraph.

Today’s selection covers a variety of examples. Two of the mood changes – when Kellyn first feels threatened by the milk guy and when she begins to sympathize with him – are buried mid-paragraph. So is the moment of shock when she spots the sinister man staring at her. The moment when the milk guy first starts dumping milk does begin a new paragraph, but the writer could emphasize it even more by giving the sentence its own paragraph. Her decision to ignore the man in the suit is given its own, single-sentence paragraph, even though it’s a relatively minor development.

This confused emphasis makes it hard to track how Kellyn’s reactions build over the course of the scene. Take the metaphor of the eighteen-wheeler, for instance. It’s a good image, clear and powerful, but we don’t understand why she reacts to milk guy with such panic, then moments later is worrying about only finding change in her purse. If you would like to keep the metaphor, we need some interior monologue to explain her reaction.

Instead, I’ve simply cut it, and adjusted the paragraphing so that her feelings about the milk guy follow a clearer arc, and the panic she feels when she first spots the stranger continues to build.

Because it’s hard to judge the pace of a passage that’s been marked up as much as this one, I’ve decided to include a clean, as-edited copy as well, so you can get a feel for the finished product.

The man at the dairy case was clearly insane, Kellyn decided. [1] Scruffy, unshaven, tattered coat:, he looked homeless. but He didn’t quite smell the part, though, reeking more of paint than filth. The guy picked up a gallon of milk, and muttered something to himself, and put the carton back, either commenting on it or talking about the carton or to it. Interesting. ,

[Paragraph added] [2] bBut that didn’t matter. She Kellyn needed to get a jug of skim for the week. She sidled in and grabbed the nearest half gallon. The man snatched up another carton and . He peered at the label. “Ah,” he said, “ah.”

[Paragraph added] Then hHis fiery gaze fixed on her. “You.” [3]

Read MoreChild narrators can be a problem.

Children don’t yet have the experience or self-awareness to understand what’s going on around them. So if you write intimately from their point of view, using only language and concepts that they would have available to them, it’s sometimes hard to convey what’s really happening. Granted, you can describe events in enough detail so that your readers may understand things that the child narrator might not. There are times that approach can come in handy – if, say, you want to filter harsh realities through an innocent consciousness. But it’s tricky to do this without having your child pay more attention than is plausible. We tend not to pay a lot of attention to events that are going over our heads.

Children aren’t fully aware of what’s going on inside of them, either. If the child’s state of mind is important to the story, you can sometimes use a more sophisticated language than your child narrator has available to them to capture exactly how they feel. This approach works best if you keep the narrative voice consistent — if you use the more sophisticated voice from the beginning of the story and stick with it throughout. This gives your readers a chance to adjust to what you’re doing. But, again, working in a narrative voice that’s separate from your character’s voice requires considerable skill.

Splitting the difference between these two approaches, as this morning’s sample does – writing most of the narrative in the child’s voice, but slipping into a more mature language from time to time — almost never works. Readers adjust to a child’s view of the world, and suddenly that view turns more adult. The shifts jar readers, who aren’t confident they can settle into the child’s view of the world.

So I’ve edited this to keep Malcom’s voice more solidly his own. I’ve tended toward shorter paragraphs and kept the language simple. And the power of the piece comes through. Even though Malcom isn’t aware of the dynamic between his older sister and his mother, readers can see it. And Malcom’s situation is certainly dramatic. Even more so since he doesn’t understand what’s going on.

Twitch Chapter One, Surrey, England, 1833-34

Secrets

The others were right. It was – the devil made him blink and scrunch his face. Aand it was getting worse.

Read More