Posts by Dave King

A client once asked me if he should use deliberate practice to learn how to write better. For those of you unfamiliar with it, deliberate practice involves isolating a skill you need to learn, then practicing it repeatedly with mindful attention to what you’re doing. It’s more focused than, say, practicing scales on the piano — more like practicing a particular passage over and over, paying attention to what the music is trying to say. You’re training your whole mind to this one specific task. It’s a useful way to learn things like a more effective golf swing or the performance of a particular piece of music.

But it’s pretty much worthless for learning to write.

You can’t learn to manage character voice, build tension, or use concrete details through repetition. Everything in writing connects to everything else, so even if you’re writing a number of similar sorts of scenes, each scene has a different contribution to make to your story. You can’t write the same scene twice.

Of course, you can rewrite scenes, often over and over. But even when you’re on your fifteenth draft of a scene, you shouldn’t be focusing on the skills you’re using. What you do have to focus on is your characters – who they are, how they sound, what they’re thinking and feeling. You have to focus on your plot – on where your tension’s been building and where it’s going, on what your readers are learning in the scene and how it will affect them. If your attention is on your writing skills, you’re going to wind up with something mechanical when you want something organic.

So how do you learn to write? Well, speaking as someone who earns his keep writing about how you can improve your writing skills, you can read about it. Even if you can’t learn the skills you need through deliberate practice, you have to learn what they are and how they work.

You can also see how other writers have used them. When you’re reading a favorite author’s work, you don’t have to worry about how you would rewrite it. That leaves you free to concentrate on technique. This is especially true on your second or third reading, when you know what’s coming and can pay attention to how the author is getting you there. One of the things that turned me into an editor was a habit of reading favorite books over and over. I went from getting lost in the story to appreciating how the story was put together.

There’s a danger in this technique. I’ve found that, after focusing my attention on technique for decades, it’s harder for me to simply lose myself in a good book. I still enjoy a well-told story, but I often find myself thinking less “Well, she’s in trouble now,” and more “Well, the writer certainly set that twist up effectively.” It’s still a pleasure to read, but it is a different sort of pleasure than what got me into reading in the first place.

I realize this is a little self-serving to say, but one of the best ways to learn to write is through using an […]

Read MoreIn the world of opera, the chorus often plays the role of an army. But to look like a convincing fighting force rather than a small huddle of singers, the chorus is often padded out with non-singing parts — bodies who just stand there to fill in gaps. These living props are known in the business as spear carriers.

Fiction has its spear carriers, as well — shopkeepers or DMV clerks or taxi drivers who need to be there to make your fictional world seem authentic, but who play little or no role in the story. Like the operatic spear carriers, they are more living props than people.

But sometimes, spear carriers can be hard to handle without throwing off your readers’ sense of proportion. Truly anonymous strangers with no dialogue aren’t much of a problem. Though no one is going to think the waiter who brings your heroine lunch is going to turn out to be a key player in the plot, you often have to pay more attention to your background characters. How do you keep from calling more attention to them than they deserve?

I’m currently editing a story in which one of the main characters, a king, meets with various bureaucrats, scientists, and courtiers who need to populate the palace but have no real impact on the story. The author’s first instinct was to not give them names, so readers wouldn’t think they were more important than they were.

Reasonable enough, except that the king would have known their names – he had been working with some of them for years. So in scenes from the king’s point of view, it felt inauthentic to refer to them as “the master of records” or “the chief guard.” They needed names and a sense of what the king thought of them – hints of personality and backstory. But not enough to distract from the main characters in the story. The palace needed to be staffed, not stuffed.

We were able to solve the problem in part by bringing some of the courtiers back several times – the king tended to receive briefings from the same ones over the course of the entire manuscript. This eliminated some of the excess characters and let the critical ones be developed in more depth. Essentially, the characters’ roles in the story were allowed to expand to fit the attention paid to them.

Another way to get around the problem is to make all of your minor characters memorable. If even the waiters and the taxi drivers stand out in readers’ minds, then readers are less likely to assume they’re important than if only one or two of your minor characters are developed in more detail. Readers who know your methods will accept the sharply-drawn spear carriers and think nothing more of them.

I’ve written before about how Sue Grafton is a master at capturing a wealth of finely-observed, idiosyncratic details that give all of her scenes an individual feel. She does the same with her characters. For instance, here’s her description of a shopkeeper who appears exactly once in C is for Corpse and only has a couple of lines of dialogue.

I turned around. The man who stood there looked as out of place as I […]

Read MoreStart your story at the beginning, write until you reach the end, then stop. Then start your revisions with page one and work straight through from there, too. Although there is no best way to write a novel, a lot of writers take this approach because it’s the most natural. And it may work for you.

But stories aren’t always so linear. Instead, they loop back and forth, with later events affecting earlier ones. Your characters might veer in unexpected directions, plot points that seemed minor when the story started may turn out to be critical, and vice versa. The ending can change the meaning of events at the beginning. I almost never edit a client’s manuscript without reading the entire thing, because I need to know where the characters and the story end up before I can know where they should start.

This is why revising is so critical. You can’t really see what your opening scenes should be until you have the entire story in place. I’ve often had clients work with me, editing through a manuscript, then ask me to take a second look at the opening chapters, to bring them into line with the changes we’d made further along. The end of the story no longer lines up with the beginning.

It’s also critical to be willing to let go of what you’ve already written. It’s been said in a lot of different places that you have to give your characters enough freedom to surprise you. You need to give your story the same freedom to rewrite itself. It’s possible that your later chapters have taken it in a new direction. You need to be willing to rip apart and rewrite your opening chapters to fit.

Read MorePhotographer: Bwag

Ruth recently read a mystery in which the main character was staying in a room in a large, rectangular mansion. The room was described as a small bedroom but it had windows on three sides. Maybe the writer simply got involved in her story and didn’t bother to pay attention to the architecture.

The truth is most readers wouldn’t consciously notice something like that, either. But even if they didn’t, the physical impossibility of the space would probably nag at them at a subconscious level. This is why it’s important, among all the other details you need to juggle when creating your world, to make sure that the spaces you’re describing hold together physically.

Does your hero’s home contain two small rooms downstairs and three reasonably sized bedrooms upstairs? Or vice versa? Does an interior room have a window? Or too many doors? Or not enough? For locations where a lot of action takes place, it wouldn’t hurt to sketch out a diagram on graph paper to make sure all the details line up.

It’s probably not a good idea to include those diagrams in your novel. During the glory days of the puzzle mystery in the twenties, the solution to the puzzle often depended on the architecture – who had a line of sight where, whether one character could get from one part of the house to another unseen, how someone got in and out of a locked room. Mystery writers often shoehorned floor plans and diagrams into the story to get the precise details across. Agatha Christie included floor plans in The Mysterious Affair at Styles and Murder on the Orient Express, and Dorothy Sayers included one in Clouds of Witnesses. Now that mysteries depend more on insight into the characters than cleverness in setting up a puzzle, those sorts of diagrams seem quaint and outdated.

But even if your plot doesn’t hinge on architectural details, don’t neglect the effect architecture can have on your locations and characters. Nothing says grim dystopia better than some Soviet Brutalist apartment blocks.

Read More“A poem is never finished; it is only abandoned.” W. H. Auden, paraphrasing Paul Valéry

I edit books for a living, so I know it’s true that writing is rewriting. But I’ve sometimes seen clients fall into editing traps that can cause real damage to their work. Although some simply waste valuable writing time, others get so caught up in the wrong kind of editing that they either lose sight of or actually blot out their vision of the book.

Before we get into these traps, a caveat. Every writer has their own approach to writing, including rewriting. There are plenty of exceptions to everything I say here. So unless you recognize yourself in the problems I describe, feel free to ignore me.

#

Do not start editing too soon. I’ve written before about how all the elements of a story interconnect with one another to form a complex ecosystem. If you start delving into detailed rewrites before your story, with all of its interconnected character and plot threads, is in place, then you are probably not doing all the editing you need. You cannot know how a character’s voice should sound until you know who they become. Nor can you judge the importance of descriptive details or the relative weight of different events until you know where your story is going. And you may waste time editing scenes that you later cut.

It’s tempting to jump into the editing too early. You may have reached a critical juncture in the plot where you’re not sure what happens next, so you dive back into the weeds of what you’ve written so far, looking for a way forward. Sometimes this works. But more often, the editing is just a distraction. It’s better to buckle down and finish your first draft before you start delving into the details.

#

Starting too early isn’t the only trap you can fall into with your editing.

Read MoreFlickr Creative Commons: Florence Bouche

“Beneath the whole story, the subtle, imaginative reader may perhaps find a pregnant allegory, intended to illustrate the mystery of human life.” 1852 review of Moby Dick

I’m a big fan of walling off your fictional world from anything that doesn’t arise from the story itself. Anything that might call readers’ attention to the fact that they’re reading, from weird verbs of speech to an eccentric writer’s voice that doesn’t belong to any particular character to excessive omniscient narration – I tend to edit those things out. The main purpose of writing is to let readers lose themselves in your fictional world. Anything that risks breaking that spell needs to go.

Except . . .

Sometimes you can get away with weaving something into your story that transcends your fictional world. These might be allegories – characters or places or objects that mean something larger than they are, like the Great White Whale. They may be motifs – recurring elements that, taken together, emphasize some underlying theme or tie together different plot threads. You can sometimes even get away with more direct intrusions into your fictional world – I recently edited a wonderful magic realism novel in which the author wrote himself into the story as one of the characters. There is a risk that these elements will undermine the suspension of disbelief. But handled right, they can make your story linger in memory long after the plot and characters are forgotten.

Understand, I’m not talking about allegories or motifs that are part of the fictional world. Characters sometime realize that something in their lives has a larger meaning, and linked themes sometimes keep showing up for reasons rooted in the story. I’m talking about things that don’t belong to any particular character. Ahab never thought of Moby Dick as an allegory.

Ruth and I recently binged the PBS version of Galsworthy’s Forsyte Saga. Through it all Robin Hill, a revolutionary modern house, runs as a motif whose meaning evolves over the course of the story. For those of you unfamiliar with the Forsytes, the house is originally built by Soames, the brittle and grasping lawyer, who sees it solely as a prized possession. Soames also sees his new wife, Irene, as a possession. Irene sees Robin Hill as an expression of the artistic vision of its architect, Phillip Bosinney, so much so that she falls in love with him, even though he is engaged to Soames’ niece, June. These two understandings of the house collide when Soames tries to destroy Bosinney’s artistic reputation by suing him for cost overruns, a thread that ends with Bosinney’s death in a London fog. (One of the reasons Robin Hill was built was to provide an escape from the dirt and fog of London.)

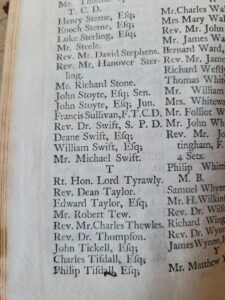

Read MoreOne of my favorite vintage bookstore finds is two volumes (out of three) of a 1742 translation by Rev. Philip Francis of the complete works of Horace. It’s interesting not so much for the translations (Francis turns Horace’s simplicity into contrived eighteenth-century rhyming heroic couplets) but for the technique Francis used to get it published. At the beginning is a list of subscribers – famous and/or rich people who paid a fee to be publicly seen as supporting the author. Among the viscounts and bishops is one “Deane Swift, Esq.” That would be Jonathan Swift, of Gulliver’s Travels.

Of course, writers today don’t have to persuade subscribers to pay for publication, selling their work on the same model that PBS uses to fund Masterpiece Theater. But from what I’ve seen of my clients’ experiences, being a successful writer nowadays involves a lot of skills that have nothing to do with actual writing.

Editing, for instance. This comes in roughly two different flavors – conceptual editing, which critiques how well your plot and characters work, and copy editing, which deals more with correct spelling and usage. (Full disclosure, conceptual editing is what I do for a living.) A lot of writers hire this out, especially the conceptual part, since it’s all but impossible to fairly critique your own work.

But good editing can be pricy, and many beginning writers on limited budgets have to learn to do it for themselves. There are <ahem> a lot of good books on what to watch for as you rewrite. Critique groups, where writers trade critiques on one another’s manuscripts, can be a help. But editing, especially copy editing, is a very different skill from writing, and it’s one you may have to teach yourself.

Read MoreLast month, I talked about the importance of keeping your writing real. This month come the caveats and other notes.

Some commenters last month asked about how keeping your writing real — using authentic and specific details in your descriptions — relates to your point of view. And, yes, what your viewpoint character notices depends on both who they are and how they’re feeling at the moment. If your viewpoint character is too thick to notice much of anything, then you have to adjust your descriptions to match.

D. E. Stevenson’s Miss Buncle’s Book is about a woman who lives in a small town and makes the mistake of writing a book based on her neighbors, all of whom recognize themselves in the story once it’s published, except for Colonel Weatherhead. He fails to see himself in the book’s “Major Waterfoot,” who falls in love with a neighbor in the book, “Miss Mildmay.” But in the book, Major Waterfoot is living a sad and lonely life that Colonel Weatherhead finds hauntingly familiar. And that recognition – or lack of recognition – leads him to court and eventually propose to his neighbor, Miss Bold.

If you look carefully at scenes from the Colonel’s point of view elsewhere in Miss Buncle’s Book, they show the obliviousness that led to his engagement. A tool shed is “a dark musty place (as toolsheds so often are) filled with worn-out tools, and a wheelbarrow and a lawnmower, and festooned with spiders’ webs . . . “ Note that the only things he notices are the things he will run into or trip over. Later we hear about a walk home when “it was still raining and everything was dripping wet,” as so often happens after a rain. Clearly the Colonel is not the most observant of men, and Stevenson shows this by leaving out details in all of his descriptions.

Read MoreOne of the more baffling problems I see with my clients is that they’re not keeping their writing real. Their stories might be full of tension and clever plot twists, their characters people I might like to know, but their writing is not rooted in life.

This problem most often shows up in descriptions. Their characters’ hair is “silky,” or wool socks “scratchy.” Hearts “pound,” muscles “ripple,” eyelids “flutter.” Sunsets “glow” or rain “pours.” They are simply writing the sorts of things that other writers have written, time and time again. It’s just as damaging when they go generic. Rooms are “large” or “opulent,” gardens are full of “flowers” surrounded by “trees,” lipstick is “red,” their characters eat “food.”

When you’re creating your fictional world, details matter. A clever story can be entertaining, but readers can’t lose themselves in your fictional world unless it feels real, concrete, definite. Clichés are tired and overly familiar. Generic descriptions are just filler, Pablum rather than steak.

Of course, most writers already know this. So why do they so often fall back on generic commonplaces and clichés?

They’re easy. They’re what comes to mind first. And they often look just good enough on the page that it’s possible to skip over them while you revise and never realize you have a problem. You have to deliberately focus to spot the places where you’ve taken the easy way out.

Other writers, I suspect, fall into commonplaces because they’re more interested in other parts of their stories. They want to get past the descriptions so they can dig into more dialogue, or they’re so caught up in the upcoming plot twist that their characters start talking banalities to get the dialogue out of the way more quickly. And all of that might be fine for a first draft. But when you’re revising, you need to rip out cliches like the weeds that they are.

Replacing them isn’t simply a matter of pulling out a Thesaurus and looking for alternatives to “silky.” You have to pay attention to the actual, real world. That’s where you go to find the distinctive, often surprising details that will make your fictional world real. For instance, the received wisdom is that teakettles whistle. But if you actually pay attention when one is coming up to a boil, you’ll find that it often bangs and pops (depending on how hard your water is) and then begins to hiss. If your readers have never noticed just how kettles boil, showing them that detail can make your fictional world feel more real than their everyday life.

To give you an example of the impact clear, reality-based details can have, Rex Stout once described Archie Goodwin visiting a witness’s apartment.

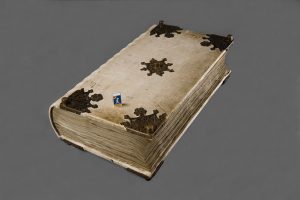

Read MoreThe Codex Gigas. Matchbox to provide scale.

I didn’t get a lot of editing done early in January. I spent too much time constantly refreshing the home page of the Washington Post and checking my Facebook news feed – I have a lot of friends who are fellow news junkies. Given what was happening, it was hard to look away.

Which makes me think of The Big Book.

The Codex Gigas was written in the early 13th-century in a Benedictine monastery in Bohemia, in what is now the Czech Republic. It is 36 inches tall, 20 inches wide, and nearly 9 inches thick, containing 310 leaves of finely-written text – it’s been estimated that 160 donkeys died to provide the vellum used. Among other things, it contains the complete Vulgate Bible, Josephus’ History of the Jews and The Jewish War, Isadore of Seville’s encyclopedia, medical works by Constantine Africanus, a treatise on excommunication, and a chronicle of the history of Prague. Essentially everything a 13th-century Bohemian monk could want to know, all in one book.

The most remarkable thing about it is that an analysis of the handwriting shows it was the work of a single scribe. And while we can’t be sure, the chronicle of the monastery included in the book provides hints that the scribe was one Herman the Recluse. In medieval monasteries, recluses were monks who lived in voluntary isolation. They were often walled into their cells, with only a small opening left for food and so they could communicate to a small degree with the public – they were often sought out for spiritual advice. (The 10th-century nun Hrosvitha of Gandersheim also wrote a comedy play involving the question of waste disposal.) Given the Codex’s size and complexity, it would have taken about twenty years to complete. Between the need for apprenticeship and failing eyesight due to poor light, twenty years would have probably been Herman’s entire working life.

Read MoreOur houseraising, in 1992. I’m in the white shirt on the far right. Ruth is the photographer.

I’m writing this while they’re still counting votes after the election, when tensions are running high on both sides and the entire country could use a little something (non-liquid) to calm them down.

The best choice for readers is what might be called “gentle books,” straightforward tales of ordinary people in mostly every-day, low-key situations. No psychotics, no wrenching twists, no gore, no vampires or werewolves or demons.

Often comic, sometimes inspiring, these sorts of books were popular from the thirties right through WWII and into the sixties. Gentle books – the work of Angela Thirkell, D. E. Stevenson, Elizabeth Cadell, and many others – offered readers well-written, character-driven stories that reminded them of their own lives. Gentle books continued to thrive through the sixties and seventies with Miss Read, James Herriot, and others. Garrison Keillor and Alexander McCall Smith are among those who carry the tradition on today.

But don’t be fooled by the familiar settings and characters of these books. They are notoriously difficult to write well. It’s just too easy to sink into either banality or saccharine gooeyness – what might be called Hallmark Holiday Special fiction.

One problem is that the sources of tension available to you are, by definition, gentle. It’s easy to keep readers on the edge of their seats when your characters are trying to escape horrible deaths or fending off the destruction of the world. It’s a lot harder to keep readers interested over whether Bertie will be able to escape saxophone lessons or James Herriot will be the one who receives a cocoa tin full of goat droppings to analyze for parasites (considered an honor in Siegfried’s practice). Yet readers need to care enough about such minor, everyday problems that they will want to keep reading and will feel satisfied with the conclusion.

Read MorePhoto credit: Ruth Julian

Unless your writing is completely grounded in urban grit, sooner or later you’ll find yourself relying on nature. You may have a character who gardens or simply likes staring out the window at a garden – or a forest, hills, parks, sea, or desert. Your plot may need a tornado, flood, forest fire, hurricane, blizzard, or ice storm. You may want nature to reinforce the mood of your story or characters. Or maybe a character just needs to take a walk.

The key to any good description is to capture the idiosyncratic details – the handful of features that make a person or a place what it is, that capture its character. This is a lot easier to do with people and human-created spaces, since most of the details were put there by individuals, who can be pretty idiosyncratic. The details that make up a natural scene come from a lot of different directions, which makes it harder to pick out the ones that define the scene.

But it’s not only that nature has a lot of moving parts. The character of a natural scene changes from moment to moment. We’re in the throes of autumn here in New England, and the foliage has a completely different feel in bright sunlight – when the colors are all vibrant and on the surface, like the paint used in elementary school classrooms – and on overcast days – when the trees seem to glow from within.

So there is no substitute for the hard work of actual observation. Go to the places you want to describe and spend some time there, watching them change and develop. Learn to read the moods of the landscape, to understand it as deeply as you understand your characters. At the very least, you’ll avoid glaring mistakes like having daffodils and roses in bloom at the same time.

Read More