Posts by Dave King

Every New Year I send out cards to former clients to find out how they’re doing and remind them that someone out there remembers they’re writers and wants to see them keep writing. I think they appreciate this – this year, one said the card brought tears to her eyes.

I’ve written before about how writing is hard. A lot of writers – including many of those who succeed in the end – have to throw away their first novel the way you have to toss the first pancake. Except that, for writers, it’s a pancake you may have poured your heart into for a year or more. And even with the novels that you keep, you’re facing some formidable hurdles in the way of breaking into print.

Some of the clients I keep in touch with have published successfully – novels or series that have collected good reviews and are selling well. But many have run aground on the hardships of the publishing trade. Sometimes, after years of struggle and rejection, they’ve either deliberately given up or just let other things in their lives sideline their writing. These are often skilled, promising writers, who have a good chance of finding a readership, but the struggle to break into print wears them down.

I don’t blame them. Until you actually break into print – or at least get close to it – the effort you put into your writing can feel like either an extravagant indulgence or a waste of time. A lot of worthwhile things – say, learning French or how to play the clarinet – need you to invest time and effort before they pay off. But with writing, your investment pays off much more slowly. You’ll start reading Maigret mysteries in French or playing along with light jazz long before you’ll hold your first published book in your hands. And you can be pretty sure that, if you stick with it, you’ll eventually master a language or an instrument. Having your book bought by a publisher is an uncertainty right up until it happens.

If you’re serious about being a writer, there are things that can help you get through the hard part. One is to focus on all the reasons for writing besides publishing. As I’ve written before writing puts you in touch with the world, with how people behave, with how their lives unfold. It lets you experience life at a deeper level. Granted, you could do a lot of that without the heartache just by practicing mindfulness, but there’s also something fun and satisfying in creating your own worlds.

You could also keep your hand in as a writer in other ways. Writing messages to family and friends or social media posts gives you a chance to exercise your love of language and hone your communication skills. Short stories can offer you more chances to break into print with less investment.

You can also look for a long-term support system, so you won’t have to go through the long, lonely stretch alone. This could be a supportive spouse or friend, a community of fellow writers, or <ahem> an editor who will pester you with a New Year’s card every year. […]

Read MoreConsider this snippet of dialogue:

“What’s her name?”

“Janet.”

“I don’t feel comfortable calling anyone by their first name, especially a woman. Do you know her last name?”

“No, I don’t. You’ll just have to call her Janet, I guess.

Perfectly good, serviceable stuff, right? Clear, fairly concise, smooth. Now look at how Rex Stout actually did it in the short story “The Cop Killer:”

“What’s her name?”

“Janet.”

“I call few men, and no women, by their first names. What’s her name?”

“That’s all I know, Janet. It won’t bite you.”

The same information, but you can hear Nero and Archie in the second version. That difference is voice.

I’ve written before about how elusive voice can be. I’ve suggested possible places to look for it and covered some of the hallmarks of good dialogue. Today, let’s take a deeper dive into how it can be done.

In the example above, notice how the word choice – and the unspoken assumptions behind the word choice — fit the two characters. Nero’s love of precise language is there in the concision and precision of the parallel “few men and no women.” The exact repetition of the question, “What’s her name,” amounts to an imperious rejection of Archie’s use of the first name. And Archie’s self-possession is there in his breezy dismissal of Wolf’s rejection. Essentially, their characters and their relationship are all there in those two lines of dialogue.

Or, take another example.

Every Christmas for the last few years, I have been sharing car-related passages from some of my favorite authors on a site for old car geeks. This year’s passage, from John Jerome’s 1979 book Truck, is also one of the best examples of distinctive character voice I’ve seen. The background: in 1970, Jerome bought, for various philosophical reasons, a 1950 Dodge pickup and spent a year getting it running again. Through a combination of ignorance and mild stupidity, he destroyed a relatively obscure part – the timing chain cover — and wrote to various junkyards trying to track down a replacement. This introduced him – and us – to Armad T. Winship, a junkyard owner in Fontana, California.

You can read the entire passage here, but here are some highlights of Mr. Winship’s letter. Spelling and punctuation are as in the original.

You might not believe it but space is and always has been the problem even before Fontana got the “middle-age spread” and passed ordinances in restraint of our trade. Ten acres is all we have left, guess how may cars that will hold and Ill send you free a dimmer switch for your truck, no rust, out of the packing box, if you come with 20 of the correct number. We have a special technique for getting the most cars on the smallest lot, no its not on their sides.

*******

I . . . drove crosscountry in a 36 Plymouth in 1940 just before the War, a sweet running little car if you didn’t try to push it in the desert. Everyone had those canvas waterbags on their bumpers so the evaporation would keep it cool. We didn’t and like to died, it felt like. I asked a man in a filling station for a little […]

Read MoreI’m a sucker for happy endings.

I’ve written before, though, that a lot of writers tend to shy away from them because they can easily degenerate into cliches. When the guys in the white hats always win and the guys in the black hats routinely go down in flames, endings start to get shallow and predictable. To avoid this, we get stories in which either nothing happens – stories that are more about creating character than watching character develop toward a climax – or where what happens to the characters is just the result of random, generally cruel fate.

I don’t buy that your only choice is between shallow, black-and-white morality and a descent into ennui and meaninglessness. Instead, I think we need to take a deeper look at where happy endings come from and what they mean. And a good place to start is the Middle Ages.

Happy endings, at their heart, are about justice. Good characters end well and evil ones end badly. But the medieval sense of justice runs deeper than the modern business of obeying the rules and making sure people who don’t obey the rules suffer. For them justice was based on the idea that any system – a person, a family, a community, a society, a nation – has a built-in structure to it, a way that it’s supposed to work. When you make choices that support that structure – letting go of a grudge to make way for forgiveness, supporting laws that protect vulnerable people from exploitation — you’re being just. When you work to break those structures down, you’re not. So according to medieval justice, stopping to let someone make a left turn to untie a knot in traffic is a just act. Picking up a shopping cart from the middle of the parking lot and returning it to the trolley is a just act. You’ve made a system, however small, work more the way it was intended.

The choices you make to support or break systems have consequences. Good people generally tend to do well because they are part of a healthier system. When evil people end badly, it’s not because some punishment’s been imposed from outside. Systems that break down tend to hurt the people that break them. To use a mechanical analogy (because, yes, I am a car geek), when you never change the oil in your engine, the engine isn’t punishing you by throwing a rod. There’s just a natural connection between clean oil and engine health.

You can see this connection between choices and consequences in Dante’s Inferno – or if you don’t have the patience for medieval Italian poetry, check out Larry Niven and Jerry Pournelle’s updated adaptation. The Inferno is renowned for the often gruesome punishments meted out to various types of sinners. But those punishments are always the direct (if graphic) result of the choices those sinners made in life.

In the circle of the betrayers, for instance, we meet Ugolino della Gherardesca and Archbishop Ruggieri degli Ubaldini. The real life Ugolio had been the leader of Pisa but betrayed the city to its enemies more than once. In one of the betrayals, Archbishop Ruggieri’s nephew was killed. So when the Archbishop captured Ugolino, he locked […]

Read MoreMary insists that Frank obey his family’s wishes and not see her anymore.

As writers, you always want to be pushing the boundaries of your reading. With that in mind, I’ve turned this month’s article over to my business partner, personal editor, fellow writer, and wife. Ruth can’t go very long without going back to her very favorite genre, nineteenth-century British novels, and her expertise far exceeds mine. Enjoy. Dave King

When I’m altogether tired of modern novels with their political correctness, literary preciousness, and occasional whiffs of meaninglessness — when I am, in short, weary of the modern world — I go back to my best reading joy: British novels of the mid-nineteenth century.

It was such a prodigious age for stories that the variety of novels written is enough to suit every reader-writer. One of my favorites is Thackery, where we meet the deplorable Becky Sharp, who lands herself in Brussels just in time for the battle of Waterloo. Thackery’s description of that world-changing carnage is the best account of the battle that I have ever seen in any source in literature or history. For those who would like to discover what kind of depressed and diminished history we women have triumphantly overcome, there are many nineteenth century sources. Think of the helplessness of a woman in a terrible marriage in The Mill on the Floss, or the misery of the sweet, young governess, Jane Eyre, betrayed by her arrogant and lordly employer.

But when I settle into a novel by my favorite author, Anthony Trollope, I am at home in a world where the characters are as modern and familiar as those around me in my own life. And his female characters are always as real as I am myself.

Lately, I’ve been revisiting The Chronicles of Barsetshire, his most famous work (with possible competition from The Pallisers). One of my favorites is the third in the series, Dr. Thorne, the account of a country doctor with no pretentions as to his profession. He is looked down on by those who cater only to the health of the upper class because he charges the same modest fee to everyone, rich or poor. He takes responsibility for his brother’s great sin in sexually forcing a dependent servant girl. After the death of the rapist, the servant falls in love with a man of her class who wants to emigrate to America but does not want to raise another man’s child. Dr. Thorne takes responsibility for the infant Mary, has her looked after by friends at a distance through infancy, gives her a fine education, and brings her as a young adult to Barsetshire, introducing her to the world as his niece.

Of course, she and Frank, the heir to the nearest stately home fall madly in love, though she is a penniless, illegitimate child, and Frank must marry money because his father has encumbered the vast acreage of his property with countless debts. The novel follows the story of how these two unlikely lovers find their happy ending against fearsome odds.

In the not-yet-formed structure of nineteenth-century novels, the author can do whatever he or she pleases and often does. So don’t be put off by, say, the […]

Read More

HAMLET, Laurence Olivier, 1948

Of all the skills writers need most, creating authentic characters is probably the hardest to achieve. Each character is unique, and the techniques that writers use to bring them to life are so complex and layered that it’s nearly impossible to talk about them in general terms. I suspect that the writers who are best at it aren’t even aware of how they do it. That’s why they often talk about finding a character rather than creating one.

Not being able to break characterization down to teachable principles is a source of real frustration for those of us who teach writing and those of you trying to learn it. But there may be a way to spot and study clear examples of genuine, deep, authentic character and see – or feel — what they have in common.

I’ve written before about how you can break out of your own head by reading books from earlier eras. Everybody’s thinking is shaped by unconscious cultural stuff that gets steeped into our heads from childhood. And that cultural baggage is where a lot of flat, lazy characterization comes from. You can never get rid of these cultural ruts entirely, but the more you can break out of them, the less likely you are to create characters who are much the same as each other and your readers. Meeting characters from the past gives you a better chance to create real individuals.

You can refine this technique further. When I read older books, every once in a while I hit a passage that strikes me with how modern it sounds. These passages can be anything from an offhand observation or a line of dialogue. But these moments represent true, authentic character – individuals with views on life that aren’t simply a rehash of whatever’s current in the culture at the moment.

One thing that ties a lot of these passages together is that they are based on close observation rather than lazy or blind assumption. Such as this passage that caught my eye in the Iliad (Robert Fagles’ translation):

He tore that Argive rampart down with the same ease

some boy at the seashore knocks sand castles down —

he no sooner builds his playthings up, child’s play,

than he wrecks them all with hands and kicking feet.

In the middle of an epic battle between warring bronze-age Greek city states, with the god Apollo stepping in, here was a glimpse of something I’ve seen in my quiet New England village. Homer had clearly watched boys building sandcastles and then knocking them down again for fun, and he gave his readers that description without embellishment. He realized they would immediately recognize it. And we still do, nearly three millennia later.

“I am heartily ashamed of myself, Lizzy. But don’t despair, it’ll pass; and no doubt more quickly than it should.” Mr. Bennett, in Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice.

This quip, too, involves some close observation – Mr. Bennett clearly knows himself pretty well. But it also shows another sign of timeless character – it comes to the surface most often in intimate, self-revealing moments. When you’re talking in public, it’s natural to conform to what the people around you […]

Read MoreYears ago, I read of an arrogant Ingénue who kept trying to upstage a more experienced actress. Finally, the actress threatened to upstage the Ingénue without even being on stage. The challenge was accepted.

The next performance included a scene where the actress was to make her exit holding a wineglass. She attached a piece of two-sided tape to the bottom of the glass, and just before she stepped offstage, she set it on a side table, hanging off the edge.

For the rest of the scene, the audience ignored the Ingénue and kept their eyes on that glass.

Sometimes your most riveting action can happen when your characters are offstage. You lead up to the key scene with enough detail that readers can see what’s about to happen, then you drop back and let their minds supply the rest. Of course, any writing is an ongoing collaboration between your words and your readers’ imaginations, but moving action offstage gives their imaginations free rein.

So when’s the right time to let your readers take over for you? Well, sex scenes. Some writers can create sex scenes whose details are steamy, reveal a character’s personality, and move the story along. But more often than not, just the fact that a couple of characters hook up is all your story needs. Besides, these scenes are notoriously hard to write well, if only because tastes vary — different people find different things steamy. If you move the explicit bits into the linespaces (as Renni and I put it in Self-Editing) then your readers can bring their own tastes and imaginations to bear. The results are often more enticing than a precise blow by blow.

Take this passage, from a manuscript I worked on recently – used with the client’s permission, of course. The main character, a professional racer, has just made a deal with her chief rival before a dangerous race – that they would both race clean, without risking one another. Then, since it’s an hour before race time, she suggests that they seal the deal, physically. Here’s the original version of the final paragraph of the scene:

She locked the door. His lips found the side of her neck. She flinched away again but then buried her neck back into his lips. She reached behind her to pull his face against hers with one hand, the other fumbling with his belt. His hand moved down her side, another up her shirt. She closed her eyes and sighed. She could accomplish a lot in an hour.

It’s hard to tell without the context, but these details don’t tell us much about the characters that we didn’t already know or move the story along in other ways. So for the edited version, I recommended that the writer simply lose the physical details, leaving only:

She locked the door. She could accomplish a lot in an hour.

[End scene.]

Another place you might want to shift the action offstage is when the emotional thrust of the scene lies in the fact of what happens rather than the details of how. Consider this situation, again taken from a recent client’s work with their permission. Helena, one of the principal characters, has murdered her husband. She then butchers him — literally, turning him into […]

Read MoreCourtesy of Jeffery, Creative Commons.

Let me tell you about a manuscript I worked on early in my career as an editor– actually when I was still apprenticing under my co-author, Renni Browne. This was back when manuscripts were still on paper and editing was done with a pencil, so both the title and the author’s name are lost to the mists of time. I’d give spoiler warnings, but I have no idea if the manuscript ever published.

Yet, this story still sticks with me decades later.

The manuscript was a fantasy set in a society on another planet with roughly renaissance-level development — well-organized city states governed by a strong, universal legal and moral code. The story is told from the point of view of an inspector – something between an inquisitor and a detective – who is called in after a soldier killed a disabled, local boy who he said threatened him. The boy’s grandmother, a retired soldier in her own right, pulls her weapons out of storage, kills the soldier who killed her grandson, then disappears. The inspector is charged with bringing her to justice.

But as he digs into the case, he discovers that justice lies on the grandmother’s side. The soldier was drunk when he killed the young boy, who was innocent. Worse, the platoon leader tried to sweep the whole thing under the rug. The inspector discovers this when the grandmother, recognizing that he’s an honorable man, sneaks into his room at night and tells him her side of the story. So despite constant pressure, the inspector refuses to back down and declare the murdering soldier innocent because that would make him complicit in the coverup. The pressure is not unreasonable, since under their laws, every unit in the army maintains its cohesion by becoming a unified whole. If one member is dishonored, all are dishonored. This means that if he judges against the platoon leader, he would be condemning every other member of the platoon to death. Still, he feels that supporting a lie would corrupt their entire society, and he cannot do it. He has no choice but to stick with the truth.

The story comes to a head when the grandmother again comes out of hiding, kills several other members of the platoon, and is shot herself. Afterwards, as the inspector is preparing the report exonerating her, the company commander orders him to let it go, to declare the soldier innocent and the grandmother guilty, for the good of everyone. Once again, he is alone, fighting for honor against the corruption and lies that would destroy everything he believes in. He feels he has no choice but to declare the company commander has fallen into dishonor.

And then, in one sudden flash, he sees that he has just condemned thousands of soldiers to their deaths. And he just can’t do it. He leaves his report unfinished and simply walks away from the situation, the army, his career as an inspector, and his entire life.

So what makes this epiphany brilliant enough that it’s still with me 35 years later?

First, it comes as a complete surprise. Plot twists in general work best when you can’t see them coming, and that’s particularly true […]

Read MoreNarcissus, staring at his reflection, from a 14th century manuscript.

Kepler’s Fourth Law of Planetary Motion: The world doesn’t revolve around you, you know.

To write well, you need to get into other people’s heads – to understand that your way of seeing the world isn’t the only way there is. This empathy can become such a habit that you can forget that some people just can’t do it. Either these narcissists imagine that everyone who thinks differently from them is plain wrong, or they don’t even realize there are differences.

Narcissists, though, can make for good fiction. For one thing, they’re a rich source of comic relief. Some of the best comic characters – Pride and Prejudice’s Mr. Collins, for instance, or P. G. Wodehouse’s Spode — are ridiculous because they are so lost in themselves, so locked into their own understanding of the world, that they can’t hear or don’t care how they sound to everyone else.

Ruth came across a good example of this in her Ngaio Marsh reading, in this case, Death at the Bar. Colonel Brammington is the chief constable who called Alleyn in on a poisoning case. He’s also a member of the gentry – a class that seems ripe pickings for this kind of humor. Fox, Alleyn’s sergeant, has just narrowly escaped becoming another poisoning victim:

“By heaven!” interrupted Colonel Brammington. “This pestilent poisoner o’er-tops it, does it not? The attempt, I imagine, was upon you both. Harper has told me the whole story. When will you make an arrest, Alleyn? May we send this fellow up the ladder to bed, and that no later than the Quarter Sessions? Let him wag upon a wooden nag. A pox on him! I trust you are recovered, Fox? Sherry, wasn’t it? Amontillado, I understand. Double sacrilege, by the Lord!”

Brammington, God bless him, is blissfully unaware he sounds like an nineteenth-century fop or that most people would not consider the use of good sherry for a poisoning as criminal as the poisoning itself.

Narcissists also give you room to grow your characters. In fact, one of the milestones of growth for children (well, most children) is the moment they realize other people are as real as they are. Having a character go through that realization in the course of your story can give you a satisfying ending. Of course, to pull off this kind of growth, your narcissist needs to be sympathetic – as opposed to the Spodes of the world. Which means you need to enter the head of someone who doesn’t know how to enter other people’s heads.

Some years ago, I worked on The Salamander Club, the story of a group of strangers who come together almost accidentally and become friends. (The book’s authors, Mats and Karin Eriksson have given me permission to use them as an example.) As the characters’ stories and relationships develop, they also explore the human condition, including people who are stuck in that early, self-involved state of development – what the Salamanders called “The Narcissus Parasite.”

We meet one of the core characters, RJ, as he suddenly breaks up with a woman he’s been with for some time. Though on his way out of her life, […]

Read More“If this were a Sherlock Holmes case, he would discover ash [at the crime scene] that came from a tobacco sold by only one tobacconist in London, who has only one customer.” G. K. Chesterton

I’ve written before about how I will reflexively edit out anything in your writing that calls your readers’ attention to the fact that they’re reading a book — foreshadowing, asides to the reader, heavy-handed narrative voice that is the same for all characters. Everything must go.

And yet, I’ve always had a soft spot for self-reference – those little observations where the writer uses characters in their stories to make comments about the stories themselves, or other stories, or the genre as a whole. The quote above delighted me enough that it’s been lodged in my memory for decades, though I can no longer remember where it came from and couldn’t find it on the internet. I remember it as being from G. K. Chesterton’s Father Brown series, but I’m not sure. Maybe readers can help. [Thanks to Christine Robinson for tracking this down — it was Chesterton.]

Self-referential asides often act as inside jokes – a nod and a wink to readers, inviting them to compare the story they’re reading to other stories. It’s tricky to do this without reminding them they’re reading a story. This is why self referential asides work best in lighter novels. And as I’ve written before, readers are more willing to hold onto suspension of disbelief when the entire novel is being played for fun. This is why The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy can get away with the book-within-the-book commenting on the action of the book.

Subtler self-reference comments on the action can often be blended into the story if they come from the characters themselves, as in the Chesterton (?) quote. After all, Chesterton’s characters had also read Sherlock Holmes. The point of that quote was to show how real police work wasn’t like fictional detective work because real policemen relied on hard, investigative effort rather than special knowledge and luck. That’s something a real detective might feel. And this makes readers less likely to notice that the speaker isn’t a real detective but is as fictional as Sherlock Holmes. The character is comparing the case he’s currently working on to Conan Doyle’s work, and that all happens within the context of the story. And, if I remember correctly, the Chesterton (?) story has the added twist that the case is eventually solved by specialized knowledge and luck.

Ruth is currently reading Ngaio Marsh’s Inspector Allyn books and finding a lot of examples of this sort of in-world self-referential commentary. (Incidentally, Ruth often contributes enough to these articles to deserve co-author credit.) For instance, there’s this from The Nursing Home Murders. Inspector Allyn and his friend Nigel Bathgate are reviewing the possible suspects, whom Nigel refers to as the “dramatis personae.” Then Allyn asks whom Nigel would pick.

“For a win,” Nigel pronounces at last, “the special nurse. For a place the funny little man.”

“Why?”

“On the crime-fiction line of reasoning. The two outsiders. The nurse looks very fishy. And funny little men are rather a favorite line in villains nowadays. He may turn out to be Sir […]

Read More

In the comments section of last month’s article on how series can go astray, someone asked how to set up a sequel for readers who haven’t read the first book. How much recapping of the first book do you need to do to bring them up to speed?

The answer, almost always, is less than you think.

Ask yourself how much your sequel’s plot answers questions you raised in the first book. Most of the time – in most mystery series, for instance — the plot of your sequel is completely independent of what came before. There may be aspects of your characters’ lives that develop from book to book. But the stories themselves are self-contained, with the end of the book answering the questions asked at the beginning. Readers don’t need a recap on the history of the friendship between Archie and Fritz in every new Nero Wolfe novel.

Or consider how an expert – Sue Grafton – does it.

The opening paragraph of A is for Alibi is all background on Kinsey Milhone – her age, where she lives, why she likes where she lives, what she does. Less than a page later, we get a paragraph on her office and the nature of her business. This is a fair amount of background right off the bat, but it’s easier to digest because we get it all in Kinsey’s distinctive voice. (“I don’t have pets. I don’t have houseplants. I spend a lot of time on the road and I don’t like leaving things behind.”) The information is also mixed with the fact that she’d just killed someone for the first time, which catches readers’ attention despite the information dump. And the background is over by the middle of page two, when we’re into the main plot.

The opening pages of Y is for Yesterday (setting aside the first chapter, which is effectively a prologue) give us, if anything, even less information, even though there are 24 whole books of background behind them by this point. Same breezy voice (“I’m also single and cranky-minded, to hear some people tell it.”). Same quick summary of Kinsey’s living situation, her landlord, and the weather at the moment. Same shocking revelation — that she was recently nearly killed and has since gotten a concealed carry permit and stopped jogging at night – to heighten the tension. And within just a couple pages, we’re in the middle of the current case.

The recapping question gets trickier when the plots of the two books are sort of intertwined – where what happened in the previous book affects decisions made in the current one. Over the 32 books of Anne Perry’s Pitt series, Pitt moves from being a police inspector to being knighted by Victoria. In between, he goes through various career ups and downs, and his feelings about recent changes affect how he reacts in the current crisis. When this happens, Perry inserts only as much information as readers need to understand what’s going on.

If you’re in this situation, you can also work background in unobtrusively with interior monologue – current events remind your characters of what came before. Or you can have a recurring character fill in a new character […]

Read MoreHolmes dealing with his Nemesis

I’ve been reading some of the last few of Anne Perry’s 32 Thomas Pitt mysteries, centered around the late 19th century detective. (Sadly, Ms. Perry died in April of last year. She will be missed.) It’s been fun to watch how Ms. Perry developed her skills over the course of the run. For instance, she did eventually kick the habit of describing faces as a way to convey emotion. But these last few books show a problem common to a lot of longer series – feature creep.

At the start, Pitt solved murders as a police detective in London. As the series went on, he tracked serial killers, then battled conspiracies within the government. This got him kicked out of the police, but he was picked up by Special Branch, where he continued the fight. Toward the end, he saved the reputation of the Crown Prince, the life of Queen Victoria, and ultimately the Empire. And while Ms. Perry’s skills as a writer made much of this plausible, mostly by rooting it in Pitt’s character, I still wonder, if the series had continued for a few more volumes, would Pitt have prevented WW1?

There are lot of good reasons for writing a series. One of the pitfalls is, how do you keep from repeating yourself – the Bond books get formulaic pretty quickly — without pushing your stories to increasingly high stakes? A lot of great series run into this problem. After Doyle tried unsuccessfully to kill off Sherlock Holmes, the stories grew more unfocused. Watson’s wife disappeared, a lot of stories were nostalgic looks back at decades-old cases, and Holmes eventually retires and raises bees. The series ends with Holmes and Watson coming out of retirement to shut down a German spy operation on the eve of WW1.

One way to keep a series fresh is to introduce a nemesis – an ongoing villain to give the villain’s side of the story as much continuity and growth as the hero’s. A nemesis lets you reveal new details of how deeply they have their tendrils into society, giving the hero new and deeper flavors of evil to overcome with each book. In Pitt’s battle with the secret society within the halls of government, he uncovers links to colleagues around him he wouldn’t have expected. Rex Stout gave Nero Wolfe a nemesis in the form of criminal mastermind, Arnold Zeck, whom Wolfe pursued over the course of three novels. Even Doyle helped speed Holmes to his death by introducing Moriarty.

But nemeses rarely last for long without themselves becoming formulaic. The existence of SMERSH didn’t keep the Bond books from repeating themselves. Arnold Zeck only lasted for three novels before Wolfe managed to take him out and return to mysteries with a smaller, often more personal focus.

Another way to keep a series from falling apart is introducing new characters or new revelations about old characters. Elizabeth Peters’ Amelia Peabody Emerson series, which runs from late Victorian days to the thirties, is primarily centered around Amelia, her husband Radcliff, and their immediate family, all Egyptologists. But the cast eventually grows to hard-to-manage proportions. We meet various distant cousins and […]

Read MoreOnce again, serendipity gave me this month’s topic. Not long after I put up last month’s piece on cultural appropriation, the New York Times published an article on the controversy around plans to rewrite the works of Georgette Heyer. Ms. Heyer, who wrote from the 1920s to the 1970s, essentially created the modern Regency romance.

She’s delightful to read in a lot of ways. I love her use of early 19th century language, but her Jewish characters are cruel stereotypes. Her estate has agreed to a new edition of her books with the anti-Semitism edited out. It’s about time.

The NY Times article argued both sides of the question. Readers are generally smart enough to see that things were different in the past, so posthumous rewriting to fit more modern sensibilities is unfair to the author. On the other side, the racist language of the past may be so offensive that some readers will be unable to read it at all.

In Ms.Heyers’ case, the offensive characters are relatively minor and easily rewritten to erase any antisemitism. In fact, because the characters are stereotypes, the book is stronger without them.

In other cases, the racism is so interwoven in the narrative that the story can’t be saved. For instance, I couldn’t get through Gone With the Wind. I mean, yes, great characters, wonderful romance, historic sweep, all of that. But I couldn’t get past the Lost Cause narrative – that the Confederacy may have lost the war, but, gosh darn it, they were right all along. The book can be taught in academic settings, where a teacher can give the cultural context, but by now it is more a historical document about the bad old days than popular entertainment.

Then there’s Booth Tarkington.

The house I grew up in didn’t have many books, and I think I read all of them – my older sister’s Bobbsey Twins collection, Oliver Twist (when I was far too young to follow it), a 19th-century edition of Pilgrim’s Progress, with woodcuts. And Penrod and Sam, a collection of short stories by Booth Tarkington. Later in life, I got hold of the first book in the series, Penrod.

Both books tell stories of Penrod Schofield, a boy growing up somewhere in the Midwest just after the turn of the 20th century. Two of Penrod’s friends were black, the brothers Herman and Verman. (That is correctly spelled, by the way. As Herman explains when they first meet Penrod, their parents just like rhyming names — they also have an older brother Sherman.) Because Tarkington was a product of his time, the brothers are often described using racist language. But . . .

In one of the stories from Penrod, Penrod has to stay in town while most of his friends visit relatives in the country to escape the summer city heat. While on his own, Penrod meets a bully, Rupe Collins, who menaces and humiliates him. And in one of the nice bits of characterization that make Tarkington worth reading, Penrod falls straight into hero worship. He starts spending more time with Rupe and emulating him. When Sam returns from the country and runs into Rupe and Penrod, Penrod encourages Rupe to bully Sam the way Rupe bullied him. Rupe is […]

Read MorePhoto courtesy of Lost Places

As so often happens, last month’s comments section inspired this month’s column.

The commentor had written a fantasy story for a competition, and in order to create a sense of a strange and exotic world in as little space as possible, pulled a number of details from ancient China. The judges liked the story but ultimately rejected because they felt the commentor was writing about a culture not her own. As the judges said, great writers had done this in the past, but “nowadays, ethnicity and authenticity are more significant.”

So . . . when it is appropriate to create characters who belong to another culture or race or gender or orientation – someone with very different life experiences from your own?

First, a caveat. I am a 63-year-old straight white man who grew up in a thoroughly homogeneous culture – Wyoming Valley, Pennsylvania. Nearly the entire population was white, primarily settlers from Connecticut and Philadelphia overlaid with immigrants who came over from eastern Europe in the nineteenth century to work the mines. A mixed marriage at the time was Polish Catholic marrying Italian Catholic. I’ve never had to worry about the possibility of being shot during a traffic stop or that my family would cut off contact because I fell in love with the wrong person, and I’m sure I take that privilege for granted.

But given that caveat . . . part of the art of writing is putting yourself in someone else’s head. It should be possible to do that even with a character who has had very different life experiences from your own. That is, after all, what imagination is for. Abandoning this approach to fiction is what gave us the old joke about MFA programs producing a lot of first novels about MFA students struggling with their first novel.

On the other hand, stretching your imagination too far can present some dangers. Cultural appropriation is a thing. If you try to place your story in a culture different from your own or center your dramatic tension on the hardships faced by characters very different from yourself – i.e. write about experiences you haven’t lived – you run the risk of being shallow or exploitative or both. How do you put yourself in the head of someone very different from yourself without offending the very people you’re writing about?

First, this largely applies to realistic stories set in the modern world. If you’re writing from the point of view of a twelfth-century French peasant and get the attitudes wrong, you’re only going to upset a group of medieval historians. If you’re writing from the point of view of a methane-based floating jellyfish living in the clouds of Jupiter, then you don’t have to worry.

And most of the time, the question never arises. Most writers base their characters on themselves, so they tend to not stray too far from their lived experience to get their stories told. But sometimes, for dramatic reasons, you’re called on to write about someone who is further from yourself in critical ways. What should you watch for?

Back in 1999, I read an article in The Atlantic Monthly that stuck with me: “ Read More

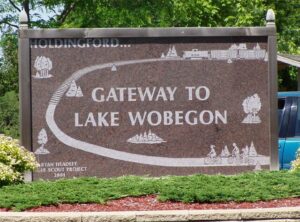

Barchester, Yoknapatawpha, Middle Earth, Lake Wobegon.

Most of the time, a setting is just a setting, a convenient place for the action to happen. If you pay attention to unique, telling details, you can push your settings to something fresh and authentic, even something that can influence the mood of your characters and shape the scene. Then there are locations that are so memorable that they stick in the mind afterwards as much as the people who live there. The settings become characters in their own right.

How? What makes a setting more than just a place?

Details for one. For settings that are just background for a scene or two, you can get away with a few key details to jumpstart your readers’ imaginations. Settings that become characters have deep roots, a history and a story arc about how they got where they are. Regular readers of Garrison Keillor’s work know when the first Norwegian bachelor farmers moved into Lake Wobegon, how it missed having the railroad run through town, and the surveying mistake that led to its not appearing on maps. They’ve got enough granular detail that readers can imagine themselves moving through them, walking from the Chatterbox Cafe to the Sidetrack tap.

Then there’s the way the location interacts with the other characters. I’m not just talking about the way a place can shape who a character is. I’m thinking of a real relationship between characters and their settings, one that flows both ways. I’ve written before about how one way to bring your characters to life by how other characters see and react to them. Locations become characters when other characters treat them like characters — when they love or hate them enough that it changes the direction of their lives.

Places seem to come to life more easily in more gentle books — Barchester or Thrush Green. When your characters are fighting for their lives, they don’t really have time to react to their surroundings. I’ve read that Alexandre Dumas’s stories don’t actually take place in France. They take place in generic places that are good settings for swordfights.

Finally, places that become characters can have their own story arcs. I’m currently working on a novel about a family living on a small holding in India that’s been in their family for generations. The father works hard and takes risks, but he manages to earn enough from this little plot of land to launch his children successfully into the world – careers, good marriages, a chance to follow their dreams. Along the way, we hear a lot about the land and what it produces – the stream that feeds it, the rubber and coconut trees, the tapioca plants, the chickens and cow. It’s clear the land nourishes the family, even if it enables the next generation to move away.

It also provides a plot arc that ties the story together. The stories of the children, while sometimes dramatic, are largely isolated from one another – more like a series of short stories. What ties them together is the relationship of the family to the land. And when some of the children move back to it at the end, it feels almost like the final scene of […]

Read More