Posts by Barbara O'Neal

Let’s talk about procrastination. That is, in case you haven’t named it, what you’re doing when you bake cupcakes, or work on that hobby, or clean all the baseboards, or doom scroll for hours instead of writing.

There are always reasons, large and small, not to work. My mid-back has been bugging me a lot. I’m worried about my mom, who doesn’t worry enough about herself. I have three cats who are all fifteen years old. Fifteen years old, people!

And you know…waves hands…the world. The terrors.

Yes. All those things. All the things distracting you, too.

But I’m here to tell you it’s time to get back to work.

First of all, it’s never about just procrastination. Something is always beneath it, something keeping you stuck, avoiding the page, avoiding even the place where you ordinarily write. What gets in the way of writing for you? Serious question. Think about this. What, exactly, is getting in your way?

The reasons for procrastinating are not all massive, big problems and thoughts. Often, they’re small things cluttering up the writing space like keys and mail on that one counter in the kitchen. Here are the three main things that get in the way:

Fear (also maybe anger)

Distractions

Real Life

FEAR AND ANGER

The first, fear and anger, cover a lot of ground.

That the work won’t be good enough

That you’ll reveal too much about yourself

That it won’t be as good as your last work

That your 8th grade teacher was right—you are a lousy writer

That the work is too serious

That the work is too frivolous

That the work is too “out there”

That the work is too bloody, too sexy, too violent, too quiet, about the wrong age of people, not very fashionable, too long, too short…fill in the blank

And then there are the other fears, about disappointing the people in your life, about worrying what will happen if you give so much time and attention to writing, taking it away from family, children, friends…and nothing ever comes of it. At the moment, a lot of us are fearful that there just not be any point.

There is a point. Trust me.

Anger is fear’s cousin, but it’s a lot more destructive, and people often avoid naming it because it feels shameful. Some things people get angry about are:

The unfairness of the publishing industrial complex

The fact that so and so got the deal you deserved and you are way better

You could write more if…..this one thing changed (you had a more supportive spouse, you could reduce your hours, you didn’t have a toddler…) Insert your own.

Are you angry? Is is getting in the way of your writing time?

If any of those fear or anger prompts resonate, I suggest you write them down. Naming a thing can rob it of a lot of power. If you are so inclined, journal about them or do some timed writings.

DISTRACTION

We live in a world that is more filled with distractions than it ever has been. We are addicted to our phones, texts, social media hits, emails, games, streaming, etc.

This is probably the most challenging aspect of writing in the modern […]

Read MoreOn my studio wall, scrawled in my own handwriting on a long Post-It is, “Art uses us to reproduce itself. Even bad art takes courage.” I’ve looked all morning to see who said this bit of wisdom, but I haven’t found a source. It might have been in a class or a meeting and someone was brilliant so I wrote it down.

Attribution aside, think about those words. Art is using us—me and you—to reproduce itself, to multiply in the world, to spread itself into new cracks and crevices of despair or delusion or exhaustion. It needs us, our hands and heart and heads, to focus on bringing our little piece of Art into the world. It’s an idea I come back to again and again. Madeline L’Engle says it another way, that a book or a piece of writing comes to the artist and says “enflesh” me. What I like about the addition of the bad art bit is that it makes less of the whole…magnificence we imagine into making Capital A Art.

Because really, once we start taking it all too seriously, we lose the thread. The process isn’t about making great art. It’s about making art, full stop. Writing and writing and writing. Writing on good days and bad, showing up for the art spirit to use us as it will. Showing up when you’re in a successful phase and when you aren’t. When you are published and before that happens. Whether critics love you or ignore you.

Early this year, I started a Substack. My nerves were fraying by all the madness in the world, and I would find myself wandering anxiously, leaping from one world stage disaster to the next, frustrated and impotent. I felt myself despairing, weeping about lives lost and things over which I had no control. The firebrand within wanted to go out and rail about it, march…something.

But the wisdom-keeper who is slowly emerging from my belly said that was not the right answer. To calm my nerves, I need to notice and write about things in the world that were good, even if it all falls apart in chaos and despair. As Mary Oliver exhorts us, I needed to notice the wild geese, flying over, even now.

So, to give myself peace, I write about cats and watermelon and how ridiculously amazing that you can feel that single piece of hair on your arm. I’ve written most of them on days when I felt most overwhelmed by the news, a measured counter to the darkness. It helps. Tremendously.

Unfortunately, because Substack is social media even if it feels a bit elevated, I started reading other writers. Some of whom write impassioned or clever analysis of the world. A worry began to creep into my thinking about what I was doing there. I began to wonder if I was letting down The Cause(s) by not using my voice and my platform to address the ills in the world. So many to address, after all. I started fretting that to write about beauty and wonder and calm was a cop-out. What will those little essays do to feed the hungry or house the poor or end the […]

Read MoreFinding ways to deepen characterization

Over the holidays and now into the dark days of winter, I’ve been re-watching The Sopranos. A lot of former favorites don’t hold up, but Tony Soprano is a masterpiece, a combination of great writing with the perfect actor, and I’ve been enthralled. Really, the detail work in the show is remarkable and worth studying. (The New York Times published a guide to rewatching here.)

As I studied the writing, in this and a few other things over the break, I have been working on a theory of character rooted in two things, the wound and the contradiction.

The wound is the simple truth that every being carries with them a wound, a defining pain. The contradiction is that thing that sticks out in their personality or actions that is contrary to every other thing. Together, these two things will do a lot of heavy lifting to elevate your characters and make them memorable.

First, the wound. This is that thing that shapes them, a scar or mark or a memory they carry like a bag of rocks. It’s the think they can’t get over even (or especially) if it seems they’ve put it to bed. My grandmother’s father died when she was eleven, orphaning her and sending her through a long series of homes with relatives until she was old enough to make her own home.

I’m sure it’s not difficult for you to pick out a wound for yourself, maybe lots of them. The one we want for a character is the big one, the hard mark. A loss, probably, something that spun life in new directions.

Tony has been one of my favorite characters to teach for a long time, and I found even more to love this time around. He’s relatable and conflicted and piercingly human, but he’s also this tragic archetype that will never escape his fate.

We can relate to Tony Soprano because despite his status as a mob boss, he is everyman, a guy with a lot of responsibilities and a high-pressure job. He suffers panic attacks. He loves his children. He really listens when people talk to him. He’s a toucher, he puts his hands on people in gentle ways. By the standards of his world, he has absolute integrity. He rules his kingdom and his world with fairness and honor. He tries to prevent wars and unnecessary killing. He rewards loyalty. And he has an absolutely horrible mother he still wants to please.

Tony’s wound is his mother. She is a cruel and distant woman who is never satisfied, but somehow, Tony keeps trying. He can never be the fully realized man he wants to be because a big part of him is still that deeply wounded little boy who loved the mother who was cruel to him.

In the also remarkable television show This Is Us, all of the family members suffer from the same wound—the untimely death of the father of the clan, Jack. Each of them has suffered in a particular way, each not-coping with the wound in ways that profoundly affect their lives moving forward. One is a famous actor with addiction and insecurity issues, another a seemingly high-functioning professional with anxiety that can lay him out, […]

Read MoreEarlier this week, my massage therapist called to remind me that we had an appointment that started…five minutes ago. Rushing in, hair askew, I apologized, and admitted that I used to have a lot more trouble with things like appointments before the iPhone was invented. It usually reminds me, twice, but we changed the time and I forgot to add the alerts, and…

She gently interrupted my whittering. “You’re just creative. That’s how it is.”

As artists we’re often forgiven for being scattered, losing things, forgetting commitments, and for good reason. It’s not laziness or lack of respect, it’s just that highly creative people are often lost in another world, with only a tenuous connection to this one, where the physical world of time and space and money and other humans exist.

But I have to tell you, I hate being late. I hate missing appointments. I hate feeling like the world is full of wind, knocking me around at its whim. I dislike clutter and mess. I hate to have nothing to cook for dinner so that I’m eating frozen macaroni and cheese for the third time in a week.

Left to my own highly creative, scattered mind, that would be the constant state of things. In fact, it was always the state of my life as a young woman and young mother. Things were often forgotten, or insanely messy, or I lost my keys or forgot appointments or we ate crappy meals because I forgot to plan.

It made me feel like a failure. Why couldn’t I juggle the world the way other people did, like my sisters and my friends?

The secret is so simple. Planning and routines. Good habits. I hate to sound like a self-help cheering squad, but honestly, I am a die-hard planner these days, and it goes along nicely with my diarist side. I can plan and then check things off to the satisfaction of the diarist who wants to know exactly what we’re doing with our days.

Learning to plan started when I began to write novels under deadline. At first, sometimes those deadlines were insanely tight—three books a year while running a household of elementary school children and making a budget based on advances work. I had to know what and when and where I was working, where I would be at a given time, and to do that, I made calendars with color coding.

It didn’t work that well.

I tried several systems. The calendar. There was a thing called Sidetracked Home Executives that used a file box with color-coded cards divided into daily, weekly, etc tasks that helped me stay on top of things for awhile, but it fell apart, too. Kids took priority, then work, then high nutrition over food I could fix in 10 minutes because I forgot to thaw anything. (Pre-microwave, young friends.)

Over time, I tried and discarded dozens of systems. And then came two life-transforming tools: the iPhone and the bullet journal.

I love the bullet journal. Planning, it turns out, is a deeply satisfying activity if you bring some color and systems into it. Everyone uses the BUJO differently. I’m not in the superfancy camp of little boxes to check off or special divisions for every one of my goals (though, you go if […]

Read MoreI saw whales this morning as I made breakfast. They moved along the water, blowing spouts as they looked for their breakfast. My husband and I each peered through the window with our binoculars, watching in wonder. “Oh, another one!” “Did you see that?”

And then we sat down to oatmeal and coffee, still looking hopefully through the windows, even though we probably won’t see any spouts without the binoculars. We’re quiet, happy. We know they’re out there, even if we can’t see them.

Every morning, and sometimes in the evenings, I walk on the beach. Most of the time, there are mussels and the broken pieces of crabs left by seagulls and crows, but sometimes, I find sand dollars or starfish dislodged by rough waters. An entire diorama unfolds on my kitchen window, agates and shells and the sand that has become my unrelenting companion.

On my watch, I have replaced my altimeter with tide tables, and my bookshelves are filling with books on ocean life and tide pools and birds. Every day, I learn something new, something amazing. Little things, like why my sunglasses get so gross (salt), and big ones, like the fact that a pod of whales hangs out due west. A big rock a mile down the beach houses seals and their babies, and hundreds of seagulls and oystercatchers and common murres. I’d never seen an oystercatcher before I lived here. I’d never seen whales spouting, or a seal beaching to have a baby.

It makes me feel 10 years old, alive and interested in everything. I’m learning which plants will survive salt winds and which ones the deer will leave alone. It’s as if a door has blown open in my brain, revealing a wild new landscape. Entire estates are open to my writer self, land ready to be explored.

It’s exhilarating.

A year ago, if you had told me this would be where we were now, I couldn’t have conceived of it. I’m a third-generation native of Colorado. I’d just remodeled my entire house and created the kitchen of my dreams.

We’d talked about living on the beach for a long time, off and on, but in the way we talk about a lot of things—what we’d do if we won a big lottery, or what kind of house we’d buy in the mountains to seduce snowboarding children to come visit more or the list of travels we’d like to enjoy, the Orient Express and a long ocean voyage on a luxurious liner, a trip to China’s Great Wall.

But until we traveled to the Oregon coast on our honeymoon in September 2021, the beach house idea was mostly theoretical. Too expensive, too hot, too many animals to realistically move between two houses.

I’ve loved the ocean madly since I was seven and my grandmother took us to the beach for the first time. It’s a clear, powerful memory, standing on the sand, watching the waves roll in. I didn’t have the language for the way it made me feel, but it was the most magnificent thing I’d ever seen. All that water. All that power, all the eternity and movement.

Over the years, I’ve spent a lot of time on those central and southern California beaches, getting there as often as I […]

Read MoreA short time ago, a minister I knew passed away. We had not been in contact for quite a long time, but it was still piercing. He went too young, and it was a surprise, and as we all know, those are the deaths that catch us off guard, and I found myself thinking about him, about legacies, and what I learned from him. His most compelling physical trait was a twinkle in his eye, like he knew something magical he was about to impart.

And he did know magical things. The best thing I learned from him was something that keeps me company all the time:

What is mine to do?

What is MINE to do?

It’s a great phrase to keep in your back pocket. It can help sort out big and small questions alike: a busy holiday meal with too many people: what is mine to do here? Everything to make it the most perfect holiday of all time? Probably not. It’s probably more like feed everyone and make sure they all have a place to sit.

And a big question like, in writing, what is yours to do?

This is a pretty magical longing, this desire to write. Writing is healing, not just for you, but for the people who need your work, and I don’t mean in a self-help, elevated, or even literary way. Books don’t have to be mighty, big things to be powerful. Who among us has not been saved by a book, maybe many times?

I sure have been. So many times.

What is yours to do?

Who do you want to communicate with? Think about that. Maybe it’s your depressed, despairing 15- year-old self. Maybe it’s your professor from junior year in college, or your mom, or your future self, or the woman who is going through a divorce and doesn’t know how to get through it.

Elizabeth Gilbert wrote that book, Eat Pray Love, and the women who responded in such enormous numbers knew exactly what she was saying to them. She was saying, it’s going to be okay. You can do this. You will find magic if you are true to yourself.

Madeline L’Engle writes in Walking on Water, her marvelous book about being true to your art, “If you don’t do your work, it might not ever get done.”

I’ve been hearing so much worry about AI writing books, putting us all out of business, but no one, especially a computer, can write your books. It’s impossible. Your writing is as unique as your life, as unique and strange and rare as the very fact that you are a being that is one of a kind in all of time and history.

It’s staggering to think about, actually. No one else has ever been you. No one else will ever be you, and even if you’re cloned in some future scenario, that clone won’t even be you, not really. It won’t have fallen down at age four and had to get stitches in its right hand. It won’t ever be able to have all the conversations you’ve had, read every newspaper column, kissed exactly the same people, taken the same walks. You are unique, and your work is unique. In all the world.

That’s mighty stuff, man.

What is yours to write?

As a […]

Read MoreI have been thinking a lot about particularity. The particular particularness of life, and how intensely important it is. As a writer, I need to pay attention to particularity, understand it, drill down.

A story to illustrate:

On Easter this year, my big, cross-eyed rag doll cat went walkabout. I say walkabout because it feels less painful, as if he decided to go explore the world and have adventures, but what really happened is that he found a breach in the fence and escaped to see what he might see, and got lost.

It was terrible. It snowed. It was cold and horrible and wet and windy. He was never a good hunter and I knew he would be hungry unless someone fed him. I felt I’d let him down, and spent hours walking my neighborhood, calling and calling. Up one street and down the next. I stood on the top of the ridge, where all manner of things live, such as coyotes and rabbits and snakes, and called some more. I posted his face on every Facebook site I could find, and paid for the special pet finder services to feature him. Every hour, I checked the Humane Society pages.

I had two phone calls, but other than than, nothing.

Nothing, nothing, nothing, nothing. I prayed and lit candles and made a special appeal to my father, lover of cats, to help him, and because I was in a class to learn to paint retablos, I chose Saint Gertrude, patron saint of cats, and painted Neko in her lap, held safely.

My partner kept saying, “He’s friendly. He’ll be fine.” Or, “Someone has decided to keep him.” I thought about how many cats must live in the subdivision where we were staying. Hundreds? A thousand? I scanned the lists of lost animals, feeling the specific sorrow of each cat parent, thinking we want THIS animal back, safely.

This particular cat, the only cat in the universe just like him. The only one. It doesn’t matter if there are millions of cats in the world, thousands in the neighborhood. None of them were Neko.

For seventeen days, my heart ached. I missed the way he head butted me. His love bites. His very, very quiet, insanely healing purr. I have never had a cat like him, the ambassador of the world, and I hated imagining him lost and lonely and afraid.

On a Wednesday night at 9 pm, I had a phone call from someone who was obviously a young guy, and he asked if I had lost a cat, and did he maybe have a collar, because in the pictures he does, but this looks like—

Read MoreA few years ago, I became obsessed with the way storytellers play with memory. I started noticing it with The Affair, which is only very good the first season or two, and then more urgently with This is Us, the story of a family in Pennsylvania, from the meeting of the parents through the current day (and sometimes jutting forward into the future).

Both shows explore memory and how we see things differently according to who we are and what kind of emotional impact the moment has on us. You’ve had this experience—arguing with a sibling or a long-time friend about the details of an event ages ago. What actually happened?

The truth is: whatever happened in each person’s mind is what really happened.

As a novelist, this single thing fascinates me. How do our memories shape us? What part do they play in what happens to us and how our lives play out? I’ve always played with memories and family legends and narratives a lot, but I worked with memories heavily in When We Believed in Mermaids, two sisters telling the story of their childhood and how it influenced each of them to become who they are, twenty years later.

Why do our characters do what they do? What brings them to the moment in time where we are beginning to write about them? How are they formed, what do they know and how did they get to know it?

It isn’t the objective facts of what happened, but the experience of those moments and their interpretation that bring out the power. How we use memory to slant and explore each character is a very powerful tool.

This both is and is not the same thing as backstory. Chunks of backstory in the authorial voice can be distracting and even boring as the reader wants to rush forward to what’s happening in the current moment. But memories, layered in throughout in the character’s viewpoint, in relation to whatever is happening in the story, can add depth and breadth and, most importantly, a sense of verisimilitude to the tale. Not factual truth, but emotional truth.

How does this work? Let’s try some examples. You might want to go ahead and do some writing, but at least give the memory exercises a try.

Exercise #1

Read MoreOn my office door is this little sign, Discipline, Priorities, Boundaries. It comes from the teachings of the Stoic philosophers. I printed it out during a particularly bad week in the middle days of quarantine, when the abject terror for all my beloved family and friends had subsided and the boredom of not doing anything, ever, had set in. I was having trouble getting my writing done, despite a looming deadline, and would spend entire days in a fugue state, unable to recount a single thing I had done besides eat Starburst.

Starburst were my Corona habit. That waxy paper, the chewy sweetness, the burst of nerve-soothing sugar got me through a lot of anxiety. I know lots of you found some other bad habit to ease yourself through the uncertainty.

But of course, a person can’t indulge a really bad habit for very long without consequences. After a few weeks, that excess sugar started to make me feel like crap, and I knew it was just a mindless pacifier helping me to deal with overwhelming, brand-new uncertainties. Would my mother get sick? Would I? What about that grandmother dying alone in the hospital with no one to talk to her. (Of all the things, this one bothers me the most by far, and it is practically inhuman.)

We all have been through some version of this, and you know, it’s not appreciably improving. There is just no way to predict anything. We are stuck, living day to day, in this reality.

Seems like a perfect time for a writer to escape into the work. Can’t go anywhere. Can’t visit anyone. Have already binged everything on Netflix. Maybe escaping into the world of my book, a world I control (more or less), a world I invented, would feel great.

Except, like many of you, I’m sure, I just couldn’t get into it. I wrote, because that’s what I do, but it was never for long, never very much.

Which is where the stoics come in. Last year, I went to the West Country in England for research on what became The Lost Girls of Devon. In Glastonbury, my partner picked up a book of daily readings from the Stoics, a group of Roman philosophers I didn’t really know much about. We established a daily habit of reading them over breakfast every day on our travels, and kept it up when we got home.

If you know me, you probably think this is a strange fit. I tend more to the excessive (see Starburst, above) and intense than measured and thoughtful.

The idea of stoicism seems austere and rather dry, but in fact the Stoics were quite interested in living a good, full life, but they wanted to live mindfully, with good character. The writings are almost always simple, straightforward, and profound. More than anything, it reminds me of Buddhism, with echoes of 12-step programs.

Back to the lack of writing. The long days with nothing to show for them. One thing the stoics value is self-discipline, and a whole month of readings was devoted to that idea,. It suddenly came to me that maybe what I needed to do was simply do the work.

Discipline.

I tried. […]

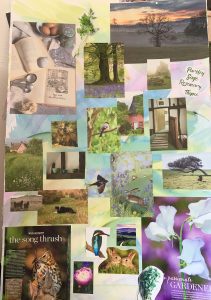

Read MoreAt the Uncon, I guided a session on right brain plotting, which was partly about music, but mostly about collage. A few people have asked about the method since then, and as this is my last post for a bit, I thought this would be a good thing to leave you with. I collage everything, and sometimes pretty elaborately. The collage for Lady Luck’s Map of Vegas was a hat box lit with tiny purple neon lights and came complete with a toy Thunderbird car. (I actually tossed this in a move and have regretted it ever since.)

One of the things quite a few people said was, “If I’d know it was a collage workshop, I wouldn’t have wanted to come, but then I had this insight/experience/recognition.” It’s a great method to let you get out of your head and let the book talk TO you.

Another thing I did for the workshop was play 30 seconds to a minute of a song, then moved to another, through a playlist that was pretty random. You can do the same thing with Spotify or Pandora or even your own bank of songs. Set the program to randomize through a big variety of songs and listen for a minute, then push on to the next. (The playlist I used for this session is here. Thanks to Angela D’Ambrosio for putting it up.)

Without further explanation, the method:

I can’t remember exactly who taught me the fine, messy art of collaging a novel—it was either Jenny Crusie or Susan Wiggs. Pretty sure Susan mentioned it first, but either way, it’s been a part of my process for a long time. Some writers scoff at this process, finding it a waste of time. Maybe some of you fail to see how an art-based project can help you build a book that’s made of words. If you’ve never tried it, however, maybe give it a shot.

The basic process is straight-forward: you use images and other physical or visual materials to create a snapshot of your book. It can be very simple or very complex, and does not require any particular skills or any kind of artistic bent. Jenny, the former art teacher, builds astonishing collages, three dimensional and with all sorts of gadgets and gizmos. Susan builds them of paper board and magazine cut-outs. I fall somewhere in-between.(This was for How to Bake a Perfect Life.)

The product is not the actual point of this exercise. It’s a process tool. Using tactile, visual, or textural materials, you get out of your logical, verbal, methodical left brain and allow the loose, associative right brain to play.

Let me stress again that you do not need artistic talent. You don’t need to create something “beautiful.”

Read More