Posts by Anne Brown

A while back, I texted my daughter.

Dinner is ready.

Her: Are you mad at me?

What? Why? I’m just saying that dinner is ready.

Her: Your period is really angry.

Perhaps you’ve encountered this yourself. These days, if your text message doesn’t end in an exclamation point, you come off as terse, and even (apparently) supremely pissed off. So, I guess dinner is ready! Hooray! Who knew we’d ever eat again?! *confetti emoji*

But there is something interesting about this phenomenon that applies to fiction writing–namely, while we toil over the perfect word choice to create the right mood and to elicit the intended emotions, those little flicks and curls are sitting there, waiting to do their own heavy lifting. They look small. But they can be mighty.

Here is a non-exclusive list of ways you can use punctuation to impact the emotion in your dialogue and narrative voice.

The Punchy Period:

Using full stops more frequently can add power and energy to your words. They can be used to emphasize an authoritarian voice because periods give the dialogue more control. For example:

“Today, you will be gathering stones from this field, beginning now and working until the sun goes down, and you hear my whistle.”

– versus –

“Today you will gather stones. You will start now. You will continue until the sun sets. Listen for my whistle.”

In which example does the prison guard command the most respect? In which example can you best hear the guard’s speaking voice? For most people, the answer to each of those questions is the dialogue with the most full stops.

But frequent full stops can also be used to indicate uncertainty, surprise, or the inability to understand; for example:

It was a ship. There. On the horizon. Yes. He was almost sure of it.

– and –

She stood. Right in front of him. Not at home with her mother. Not where she should be at all.

Frequent full stops can also show despair, like this example from Brooklyn by Colm Tóibín:

“Would you like me to call Miss Bartocci?” she asked.

“No.”

“Then what?”

“I don’t know what it is.”

“Are you sad?”

“Yes.”

“All the time?”

“Yes.”

Try using frequent end stops whenever you want to deliver an emotional punch.

But wait! There’s more.

Read More

At the WU Unconference last fall, I gave a presentation on the “meet-cute.” If you’re unfamiliar with the term, it’s that moment when your characters meet for the first time. Sometimes they click immediately (Titanic; 50 First Dates), other times they don’t (Pride & Prejudice; When Harry Met Sally). Regardless, some kind of chemistry is established between them that makes the reader want to root for the characters as a couple. It’s a typical element of every romance novel, but it can manifest in other ways in other genres. The typical meet-cute goes a little something like this:

Sarah walked onto campus as a new freshman. While she wrestled one-handed with the campus map, her Human Anatomy textbook slipped from her hands and fell open on the sidewalk to a page her mother would have censored. Embarrassed, Sarah quickly crouched to retrieve the book before anyone saw, just as someone knelt to help her. She looked up and locked eyes with the most handsome man she’d ever seen. Sarah’s heart raced.

When I say this example reflects the typical meet-cute, I mean really, really typical. Too many meet-cutes I read are all about racing hearts, or some other obvious go-to like stammering, sweaty palms, or stumbling over words and/or feet. These common crutches got me thinking. How can we better delve into our own personal experiences to come up with more unique and inspired ways to demonstrate the interior landscape of a scene? How can we show our characters’ feelings through more unique physical reactions to those feelings?

Read MorePhoto Cred: Alex Robert

With the WU Uncon just around the corner, many of us are getting excited for a writing retreat. There is the anticipation of seeing old friends and meeting new ones, the expectation of learning something new, and the chance to gain insight and inspiration for the current WIP. And while big retreats like the Uncon pack a big punch, there is also much to be gained from smaller, more intimate retreats—especially ones you plan yourself.

I’ve done a few of these with my critique groups over the years. If you haven’t put one together yourself, here are some ideas to get you started. It might be just the thing to tide you over during the Uncon’s off years.

[Before I get going, I wanted to note that I reference a number of websites in this article. I am not affiliated in any way with any of these businesses, nor have I used all of them myself. Rather, they are selected from my own research file, which I have compiled over the years for planning writer retreat weekends.]

Location, Location, Location. The location for your retreat goes hand in hand with the number of people you can invite to attend. There are, of course, places specially designed for writers retreats. For example, the Highlights Foundation offers private writing cabins in the Pocono Mountains, and offers a lodge where everyone can congregate for meals. There are smaller places, too, like this writers and artists retreat home available for rent in Wisconsin, or this one in Tennessee. In fact, airbnb is an excellent place to start if you don’t have a private home or cabin available to you.

Whatever you choose, you’ll want to make sure you have not only sufficient bedrooms, but also ample space to spread out during the day for quiet, undisturbed writing time. I also suggest asking what everyone’s writing process is beforehand. For example, many people like to listen to music while they write. Be sure that headphones are required. Others like to read aloud to themselves, or they use Dragon software as part of their writing process. The other attendees will appreciate it if that person has some space where sound can be contained and won’t bleed over into others’ work areas.

Schedule. You can do whatever you like, of course, and it’s always a good idea to ask the attendees what they want to do. However, I’ve found that providing a schedule before the event sets the right expectation: this weekend is meant for writing first, socializing second. This is particularly true because people are likely spending money to participate. The following schedule has worked well for my retreats in the past:

8:00 AM Breakfast

8:00 AM- 12:00 PM Write

12:00 PM Lunch

1:00 PM Recreational Activity to Recharge

3:00-6:00 PM Write

6:00 PM Dinner & Drinks

7:30 PM Time to Share Aloud the Products of the Day

Food. […]

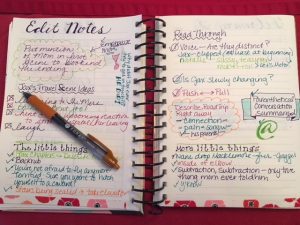

Read MoreA month or so ago, I was deep into first-pass editing. This is the stage after you receive an editorial letter that poses questions about character development, suggests adding scenes (or removing them), and encourages other “big picture” thinking. I posted a photo of what my editing process looked like for that morning, and Therese Walsh messaged me: “Please write a post about this.”

I thought that was Therese just being sweet and supportive (as is her way) because what could I possibly say about something so obvious?

But then, over the course of the day, similar comments trickled in. I was surprised, and it got me thinking that maybe…was it possible?…not everyone organized their thoughts in pictures? So I did a little digging.

Turns out, I am a visual thinker (aka picture thinker), as are 60-65% of the rest of you. When you write, do you first picture the scene in your mind, and then describe what you see? Or, do you begin to write and the scene slowly materializes as your words hit the page? If you are the former, [insert Jeff Foxworthy’s voice] you might be a visual thinker.

If you are athletic, musical or mathematically inclined, you may be more inclined to visual thinking.

Back in the 1970s,“visual” and “verbal” thinking were set up as opposites, but the brain is never that simple. Most of us think and learn in a combination of ways.

For example, Temple Grandin reports that words touch off cascades of images as her visual and language systems interact. (Otis, Psychology Today)

Poet Natasha Trethewey has such a strong visual memory that, when she studied for tests in high school, she would visually memorize her notes and then read the answers off her mental scans. (Id.)

Jessica Spotswood, an author friend of mine, gets down to editing by retyping her entire book, character-by-character, starting with page one. She says, seeing the words all together on the page visually disengages her from the specific words originally selected, and allows her to fine-tune her message.

So, this brings me back to my own writing and editing processes. Why do I do it the way that I do, and might it also help you?

Read MoreI have a daughter. She’s seventeen. She’s a fantastic writer (truly), and a big-time reader (no surprise). She’s also totally blind. And this is where things get interesting.

A few weeks ago, we were driving down the road. She was reading aloud to me from her work in progress—a fantasy that featured a blind person as the main character. Here’s a snippet of that conversation:

Daughter reading: “As the minivan approached the curb, we all turned to look, and John’s face clouded with disgust.”

“Stop,” I said. “Stop right there. Isn’t the main character blind?”

“Yeah,” she said, as if it should be obvious. She’d already told me so.

“Okay, so how did she know it was a minivan approaching? How did she know everybody turned to look? How did she know what John’s face looked like?”

Long pause…Then, from the passenger seat. “Dammit.”

This exchange triggered a fascinating conversation about points of view and author intrusion. My daughter had infused her character with a point of view that was not specific to her character’s visual impairment, but rather to every sighted character in every book she’d ever read. This disconnect caused reader/listener confusion and a lack of trust.

“How can you rewrite it?” I asked.

A few minutes later she came back with:

Read MoreI’ve been thinking a lot about empathy lately. It’s been an obvious subject of conversation in the wake of the Orlando massacre and high profile sexual assaults. Violence is often the result of one person’s inability to connect with and appreciate the value and integrity of another person.

In that regard, author Shannon Hale has been very vocal about schools not engaging female authors for speaking engagements and not promoting books with female protagonists on the premise that the author or the book won’t be interesting to boys (while not having the same concerns about male authors and male protagonists being interesting to girls). Hale recently tweeted (and I’m paraphrasing here): When we constantly tell young boys that they don’t have to consider the female point of view, that the female protagonist’s story has nothing to teach them, and even to ridicule those boys who (gasp!) pick up a book about a girl…is it any wonder why there are so many young men who cannot empathize with their female peers?

Obviously developing empathy is an important piece to cultivating a safer and healthier world, but I’m not here to bemoan current events. Instead, let me focus on the importance of developing empathy for the purpose of improving our writing. This is Writer Unboxed, after all.

Why do we, as writers, need to develop a strong ability to empathize?

Read More