Readings for Writers: Judith Ortiz Cofer and the Will to Write

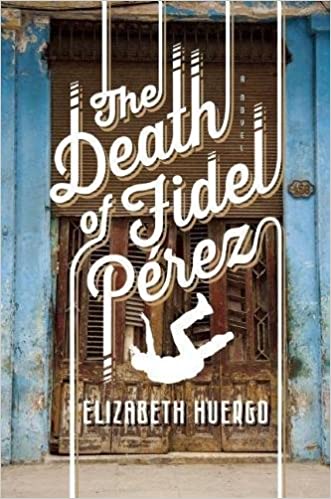

By Elizabeth Huergo | July 27, 2021 |

How did Judith Ortiz Cofer transform herself from a “frustrated artist” to a “working writer”? Read The Latin Deli, where she describes her transformation as “an act of will.” She decided to get up at 5:00 a.m. each morning, two hours before anyone else in her household. The decision became an expectation she had of herself, and the expectation developed into a daily ritual, whether she was writing poetry or fiction or dividing her time between the two genres. She completed her novel, The Line of the Sun, not by expecting an enormous swath of time to open magically before her, but by writing in small increments every day. She developed short, reflective essays and stories the same way, later collecting them side by side with poems that amplified or reframed their themes. She empowered herself by making an active choice and recognizing that the “urgency to create can easily be dissipated,” especially if you are a woman. In “5:00 A.M.: Writing as Ritual” she admonishes us to do whatever we have to do, including “stealing” time from ourselves.

How did Judith Ortiz Cofer transform herself from a “frustrated artist” to a “working writer”? Read The Latin Deli, where she describes her transformation as “an act of will.” She decided to get up at 5:00 a.m. each morning, two hours before anyone else in her household. The decision became an expectation she had of herself, and the expectation developed into a daily ritual, whether she was writing poetry or fiction or dividing her time between the two genres. She completed her novel, The Line of the Sun, not by expecting an enormous swath of time to open magically before her, but by writing in small increments every day. She developed short, reflective essays and stories the same way, later collecting them side by side with poems that amplified or reframed their themes. She empowered herself by making an active choice and recognizing that the “urgency to create can easily be dissipated,” especially if you are a woman. In “5:00 A.M.: Writing as Ritual” she admonishes us to do whatever we have to do, including “stealing” time from ourselves.

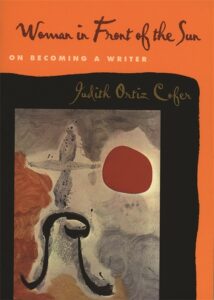

Ortiz Cofer presents the decision to write as a simple practicality. Read Woman in Front of the Sun, however, to understand the weight and complexity of her struggle to give voice to her experiences as a Latina, born in Puerto Rico and raised in the US. The essay “Are You a Latina Writer?” answers the question posed in the title. Her purpose as “an emerging writer” evolved. She wanted her work to serve as a bridge, a way of transiting across borders

Ortiz Cofer presents the decision to write as a simple practicality. Read Woman in Front of the Sun, however, to understand the weight and complexity of her struggle to give voice to her experiences as a Latina, born in Puerto Rico and raised in the US. The essay “Are You a Latina Writer?” answers the question posed in the title. Her purpose as “an emerging writer” evolved. She wanted her work to serve as a bridge, a way of transiting across borders

so that I would not be like my parents, who precariously straddled cultures, always fearing the fall, anxious as to which side they really belonged to; I will be crossing the bridge of my design and construction, at will, not abandoning either side, but traveling back and forth without fear and confusion as to where I belonged–I belonged to both.” (Woman in Front of the Sun)

To write she must separate herself out from parents “who precariously straddled cultures.” She must design and build a bridge and travel from one side to the other, never abandoning her family and sense of place, never being fearful or confused. Aside from the magnitude of the tasks she sets for herself, there is the paradox she must negotiate daily: to survive, she must be separate and unlike her parents; to survive, she must never separate herself from or betray them. This is a double bind that I understand especially well as a Latina from a sister island, Cuba.

In “A Prayer, a Candle, and a Notebook,” the sense of distance between herself and those she loves is even more stark. In this essay, faith, hope, and the notebook where she records her memories serve as the sources from which she fills her well of knowledge:

As I look deeper into myself,” she writes, “I discover that I left the place where my family’s well is located. As a writer I am always in the new territory of Myself Alone. I am looking for new lands to discover every time I begin a sentence. I carry nothing but a dowser’s wand and my need to make order, to find a few answers.” (Woman in Front of the Sun)

Ortiz Cofer is intrepid and tenacious. If you doubt it, consider for a moment what it would feel like to be “always in the new territory of Myself Alone,” forever moving across unknown spaces with a rudimentary divining rod and a hope that you will find life-sustaining water.

Here again self and art are pitted one against the other. Writing separates her from home and family, and writing is what she must do. Writing leaves her with no ground beneath her feet, and yet writing opens the narrow bit of ground before her. What Ortiz Cofer explores in The Latin Deli and Woman in Front of the Sun is her experience transiting cultures, remembering through the stories of others in order to create her identity as a writer. As the “immigration debate” heats up, pick up her work and feel the difference between history as an abstracted fairy tale and history as blunt force trauma. Listen for all the many ways a Latina can be called a spic by classmates, teachers, colleagues, and strangers on public transportation.

Ortiz Cofer in “Taking the Macho” argues that for a woman to become a writer, she must become like Charles Lindbergh, who crossed the Atlantic with “no forward visibility” (italics original). In the absence of aeronautical instruments that would allow him to look ahead, he could only look to the side and trust his own skills and instinct. “It takes balls to do anything dangerous and new,” Ortiz Cofer observes. She continues:

But we may be able to transform an anatomical fact into a useful metaphor. And maybe we need to liberate the word [macho], because unless [women] claim macho we may be doomed to a degree less of what we need for this dangerous exploration of inner space called artistic creation.” (Woman in Front of the Sun)

For Ortiz Cofer the act of writing, the expression of identity through writing, requires us to face the fear of empty space. Writing requires the will to move blindly, with “no forward visibility,” a lone figure across a vast ocean.

Ortiz Cofer “decided that words were [her] medium; language could be tamed.” Here is another act of will similar to her decision to get up every day at 5:00 a.m. Yes, she decided, she could make language “perform.” All she had to do was “believe that [her] work was important to [her] being.”

Have you made any powerful decisions about your writing? Have you read any Latina writers lately?

[coffee]

“As the ‘immigration debate’ heats up, pick up her work and feel the difference between history as abstracted fairytale and history as blunt force trauma.” That is a powerful invitation to step into empathy. As a writer, I often feel groundless, at least until my tires grab the asphalt of my story. But you describe a whole other kind of groundlessness. We who were born here take so much for granted, and being shaken awake can be jarring. I have not read any Latina writers lately. Now I know where to start.

Maybe I should claim my ‘status’ as Latina. I grew up in Mexico City from 7 to 19, and my four younger sisters (even the one with only American citizenship) are completely Mexican. I used a character with a similar background for my first, unpublished mystery novel and a half, abandoned when I got into the WIP.

When I go to Mexico, I fit in – and I don’t. My Latina worldview was subsumed in my science one in graduate school, and has never really recovered.

But it colors everything you write, who you are, where you grew up, where your family still lives. Even my fictional characters still include one who straddles that Mexican/American divide, careful to stay on the more lucrative side for herself (Hollywood) and musing that her Papi wasn’t ‘white’ enough to succeed there, and blessing her lucky stars for her ‘Nordic’ mother’s genes.

I know those threads are there, sometimes tweak them consciously, but it is background, not main story.

I have made plenty of powerful decisions about my writing, but the charism I was given is to be a voice for the way society sees and treats disabled people, and makes a straight-jacket out of what is ‘normal.’ There’s only so much room, even in a half-million word trilogy.