One

By Porter Anderson (@Porter_Anderson) | April 19, 2019 |

Image – iStockphoto: Mike Kiev

Dictionary

The people at Merriam-Webster aren’t always known for the most electrifying discussion articles about the world of words, and yet something in their brief seems to insist they produce those articles.

Usually, the one word you might have for these pieces might be nerdish. Or geeky. Or eggheaded.

Usually, the one word you might have for these pieces might be nerdish. Or geeky. Or eggheaded.

So I was delighted when a message came in from their offices that they had something I might like. “What’s In a Name?” is a collection of comments from 11 authors on their one-word book titles.

And as I read it, I realized that there really is a very distinctive impact in many one-word titles. One of the best examples I can give you on all levels is Go, the muscular Kazuki Kaneshiro novel in its English translation by Takami Nieda from Amazon Crossing. I covered it in an interview with Nieda, and, as it happens, you can get it free in the “Read the World” promotion for World Book Day right now: here’s where.

My provocation for you today is to think about this and see if you can put into words (I’ll let you have more than one) what it is about a strong one-word title that makes it what it is.

If you’d like a refresher on some singular-utterance titles:

- BookRiot produced a nice list of about 100 of them in 2017 and you’ll find it here.

- Another good list? Thanks, Goodreads.

- More? Here’s the Seattle Public Library at work.

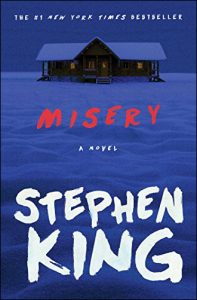

The shortest I’ve come across might be Stephen King’s It. And he’s in the Merriam-Webster piece, not for It, but for Misery. He’s quoted saying, “With Misery, it was the name of writer Paul Sheldon’s main character (he wrote bodice-rippers about a hot chick named Misery Chastain), and the situation he found himself in as Annie Wilkes’s prisoner. So the title was pretty much a no-brainer.”

The shortest I’ve come across might be Stephen King’s It. And he’s in the Merriam-Webster piece, not for It, but for Misery. He’s quoted saying, “With Misery, it was the name of writer Paul Sheldon’s main character (he wrote bodice-rippers about a hot chick named Misery Chastain), and the situation he found himself in as Annie Wilkes’s prisoner. So the title was pretty much a no-brainer.”

Another short one is pointed out by Merriam and her husband Webster: Malinda Lo’s Ash. “I’m not sure when I chose to name my Cinderella character Ash, but it seemed crystal clear to me that it was the only name she could have. Her story might begin in darkness, but she rises out of the ashes of her grief like a phoenix.”

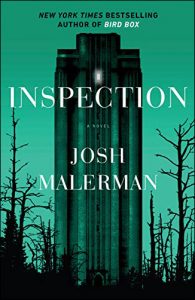

In thinking of why such titles work (or don’t), I find that single words that describe an emotionally intense construct work best on me, whether they’re an adjective (Vicious) or a noun (Inspection, just out in March from Penguin Random House/Del Rey by Josh Malerman, author of Bird Box–the October 1 follow-up to which will be the one-word-titled Malorie).

In thinking of why such titles work (or don’t), I find that single words that describe an emotionally intense construct work best on me, whether they’re an adjective (Vicious) or a noun (Inspection, just out in March from Penguin Random House/Del Rey by Josh Malerman, author of Bird Box–the October 1 follow-up to which will be the one-word-titled Malorie).

Place names used as one-word titles leave me pretty cold. Heartland. Matterhorn. Edinburgh. I think they give me the feeling that somebody didn’t want to deal with the usual duties of exposition. Exception to the place-name rule: the film title Brazil.

In fact, I think Hollywood is way ahead of us on this.

In fact, I think Hollywood is way ahead of us on this.

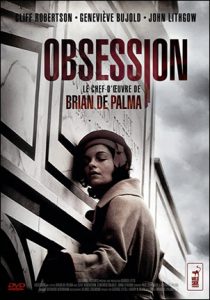

Remember Obsession? Brian de Palma, 1976, with Genvieve Bujold. I was hooked on one-word film titles as soon as I saw that thing. Inception (2010).

Here’s IMDb with a handy list of one-word film titles. Warning (not a bad title, Warning): There are 12,325 one-word film titles in this list. After three days, we’ll send somebody out to search for you.

Singularity

Provocations graphic by Liam Walsh

Now, I’ll take a stab at what I think goes into the impact of the best one-word titles, and then it’s your turn. In examples I’m using here, I’m not vouching for the quality of the book or film behind the title, I’m looking only at the title (and, as we all know, in some cases, the author or filmmaker should have stopped right there, so it goes).

I would say the strongest one-word titles do one or more of four things:

- Create a kind of profundity, deserved or not, for the word in question (Alien. Zorba. Amadeus. Solar.)

- Contain energy, whether it’s psychological, social, physical, classic, whatever–some sort of dynamic (Interstellar. Unbreakable. Insurgent. Revenge.)

- Arrive from nearby. By that, I mean they feel close to us, close to issues of the day, carrying a kind of currency that sounds like a great op-ed feels–as if someone has just, finally, summed up what we’re all thinking or feeling. (Extinction. Overruled. Disgrace, 1984.)

- And as Jeff Eugenides says in the Merriam-Webster piece about Middlesex, “A good title tells you what the book’s about. It reminds you, when you lose heart, why you started writing it in the first place.” I’d just add that this works for a reader, too. When you lose your way trying to get through something, it can really help to have an efficient handle to grab onto.

In the Merriam-Webster piece, Jeff Vandermeer says, “Annihilation came to me as a title mysteriously—I cannot tell you what my subconscious was up to. But then my conscious mind thought about it and realized the novel was about a giving up of the self to something new.”

In the Merriam-Webster piece, Jeff Vandermeer says, “Annihilation came to me as a title mysteriously—I cannot tell you what my subconscious was up to. But then my conscious mind thought about it and realized the novel was about a giving up of the self to something new.”

Chuck Wendig tells M-W: “Wanderers was not always the book’s name. Originally it was Exeunt — which is a lovely-sounding title that nobody would ever be able to pronounce or spell, which, ha ha, is not the best way to sell a book, probably. And so came the search to find another title, and given that the book begins with an epidemic of sleepwalkers walking across the country to some unknown purpose, the line ‘Not all who wander are lost’ from Tolkien had a certain critical resonance, and given the epic nature of the story, it felt apt to use Wanderers as the title.”

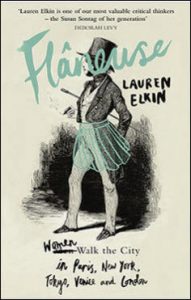

And Lauren Elkin gives M-W a run for its money with a nice definition: “Flâneuse [flanne-euhze], noun, from the French. Feminine form of flâneur [flanne-euhr], an idler, a dawdling observer, usually found in cities. … I called my book about the liberating power of walking in cities Flâneuse because I wanted to queer the flâneur, so to speak, with a change of gender reclaiming the concept of urban idling from a normative mythologized figure into one of rebellion and difference.”

And Lauren Elkin gives M-W a run for its money with a nice definition: “Flâneuse [flanne-euhze], noun, from the French. Feminine form of flâneur [flanne-euhr], an idler, a dawdling observer, usually found in cities. … I called my book about the liberating power of walking in cities Flâneuse because I wanted to queer the flâneur, so to speak, with a change of gender reclaiming the concept of urban idling from a normative mythologized figure into one of rebellion and difference.”

And before I turn this over to you, I’ll save you the trouble–no extra charge.

Collusion is already in the works, scheduled to be released April 30 by HarperCollins’ Broadside Books. It’s described as a “rollicking tale of high-stakes international intrigue—the first book in a contemporary series filled with adventure, betrayal, and politics, that captures the tensions and divides of America and the world today.” Guess who. Newt Gingrich, with Pete Earley.

Collusion is already in the works, scheduled to be released April 30 by HarperCollins’ Broadside Books. It’s described as a “rollicking tale of high-stakes international intrigue—the first book in a contemporary series filled with adventure, betrayal, and politics, that captures the tensions and divides of America and the world today.” Guess who. Newt Gingrich, with Pete Earley.

Obstruction is a book by Nick Salvato (Duke University Press, 2016)–and hey, I might have to read this. “Can a bout of laziness or a digressive spell actually open up paths to creativity and unexpected insights? In Obstruction Nick Salvato suggests that for those engaged in scholarly pursuits laziness, digressiveness, and related experiences can be paradoxically generative.”

Obstruction is a book by Nick Salvato (Duke University Press, 2016)–and hey, I might have to read this. “Can a bout of laziness or a digressive spell actually open up paths to creativity and unexpected insights? In Obstruction Nick Salvato suggests that for those engaged in scholarly pursuits laziness, digressiveness, and related experiences can be paradoxically generative.”

Now you. One-word titles. Do they work? Do they not? Why? Why not? Do you use them? Do you wish you did? Do you wish everybody would stop? Are you glad this column is over? Go.

[coffee title=”Wish you could buy Porter a glass of Campari?” icon=”glass”]Now, thanks to tinyCoffee and PayPal, you can![/coffee]

“Merriam and her husband Webster” — love it! I feel a cartoon coming on.

But hey: Merriam-Webster, a hyphenated surname just begging for a given name. Annie? Genevieve?

Seriously, Porter, I am not glad this column is over. I can use a surplus of applicable entertaining information this week. Thanks for providing it. I’m off to generate one-word titles for my WIPs. Would love to see a future column from all in the WU community who took this inspiration and ran with it to produce and publish their own one-word-titled books.

Interesting article, and I, too, love Merriam and her husband. As you stated so well, one-word titles are powerful in creating emotion and interest in the book or film. I’ve never used a one-word title for any of my novels or short stories, but it might be a good creative exercise to take one of the stories and see if I could come up with just a one-word title.

Instead of sending a rescue party to find me checking out that list of 12,000 + titles of just one word, send someone to find me slumped in my office pulling my hair out because I can’t change “A Question of Honor” to one word.

For “A Question of Honor,” you could change it to “Honor” then add a question mark. HONOR?

One word titles I’d like to get on submission (joke edition):

Submission*

*(Fifty Shades knockoff)

Jelly*

*(jazz pianist as detective in 1920’s New Orleans)

Rover*

(*Faithful dog follows dying man on round-the-world trek)

Space*

(*Experimental fiction with no words)

Gone*

(*Novella length dark thriller)

All*

(*Novella length literary fiction)

Game*

(*Fantasy)

Road*

(*Bleak dystopian)

Baby*

(*Sensitive dad romance)

Barf*

(*Gross-out comedy)

Oh loving the books coming out–why not take a word that is shouted out in the MSM about a thousand times a day. But bottom line–the book has to deliver. Maybe there is someone out there laboring on a book entitled TRUTH. My work in progress has a long title, not unlike WHERE THE CRAWDADS SING. Now is that prophetic or am I dreaming? Nice to see you Porter, Beth

One-word titles are likely more successful commercially because they’re (1) faster to read and can be printed very large on a cover, and are therefore more likely to catch the eye, and (2) easier for people to remember and communicate to other people. I think up to three words is pretty safe. It’s easy to remember War and Peace, Great Expectations, and The Hunger Games.

If a title is wordy, it can still be successful, but people start to say, “Have you read The Curious Case of…, uh…Wait, no. Was it Incident? I’m pretty sure it was ‘case.’ The Curious Case of a Dog…something something.”

Writing about long titles is irritating for reviewers, too. They start abbreviating things TFIOS instead of writing out The Fault In Our Stars and nobody outside the fandom knows what the heck they’re talking about.

Porter, I love books with one-word titles because of how evocative they can be. Almost all my WIPS (books) have one-word titles (not so the magazine stories). The working title for my first novel was DAMAGED (because both sisters were damaged, one physically, the other mentally) but as I revised it, the themes of being bound by love and setting boundaries began to emerge so in its published form, it’s BOUND. Alas, if you do a search with just the title, you get a lot of BDSM, so there are pitfalls to the one-word title too. Laughed at all Don’s titles :)

My working title for Pride’s Children for many years was Resurrection!.

But one-word titles can be depending on the reader/viewer ‘getting it,’ immediately, and understanding the connotations and nuances, and I found myself rejecting such titles in other people’s work because there was not enough to get a handle on what the background to the title was. Or the genre. Or much of anything.

And there were repeats – does one writer’s Obsession (another one I seriously considered using) make the story so singular that a word gets locked up (Inception might do that)? Or can another writer use it for something completely different without confusing ‘the fans’?

I still mourn my title – it made so much sense to me as a description to the ending of a modern retelling of the Book of Job – a character being, in many ways, back to where she was before Life (if you prefer) tested her by stripping her of almost everything she valued.

But then I found out that is the plot of many Romance novels, and that was the end of that.

And no one who hasn’t had a classic education seems to remember the allegory of Job. Our modern world is poorer for it: Job’s story is one of perseverance against pretty impressive odds.

And PC is really about much more than resignation.

Alicia, Pride’s Children is much more specific and intriguing. Resurrection has so many associations that it would not have been specific enough for your book. I remember a first-time author who desperately wanted to title her romance novel Redemption. We all tried to talk her out of it because the religious overtones would have been entirely misleading. That can happen, it seems, when the writer is so close to the work as to be unable to stand back and notice how it will appear to the audience.

I think Exeunt is a great title – very evocative – but possibly less so for those not up on old-school stage directions.