Reading the World: Translation Is Rising

By Porter Anderson (@Porter_Anderson) | November 19, 2017 |

Image – iStockphoto: Runna

Where Politics Can’t Stop Us

A funny thing happened on the way to isolationism. Some in the business believe there’s new interest in work from other languages.

I’m hopeful that some of what’s lost in the dynamics of vulgar nationalism can be found in translation.

Threatened with the un-American idea that we shouldn’t have people from “foreign” venues among us, Americans, it seems, may be waking up to the fact that we’re all foreigners here, united in world history’s grandest handshake.

And not just in the Newer World, either. In the UK–perhaps an early warning of the Brexitian crisis–The Bookseller’s Tom Tivnan and Felicity Wood were reporting a rise in revenue of 6.2 percent in translated books in the first part of 2014. At that point (about 19 weeks into that year), 112 translated books had been part of the Top 5,000 titles tracked, over 63 translated titles in the same period of the previous year.

At world trade shows this year, the “rights centers,” those big, noisy kasbahs in which books are bought and sold into new languages, have been growing fast, to the point that at the largest, Frankfurt Book Fair, we had sold out all 600 tables in its Literary Agents and Scouts Center, called the LitAg, some six months before the fair this year.

Tomorrow (Monday, November 20), we’ll have news at Publishing Perspectives of Wattpad phenom Anna Todd selling the first book of a new series rapidly into international territories, and it’s not even releasing until June 1.

The National Endowment for the Arts‘ translation fellowships in 2018 will award 22 new grants of $12,500 or $25,000 each for a total $300,000 to help defray the costs of translation from works in 15 languages and five continents. In fact, here’s a bright spot amid the crushing distress of “your tax dollars at work” in so many wrong places these days: since 1981, the NEA has awarded 455 fellowships to 404 translators working into English from 69 languages and 82 countries. NEA literature director Amy Stolls calls this “expanding the range of ideas and viewpoints.” And that’s how you build open doors, not walls.

The National Endowment for the Arts‘ translation fellowships in 2018 will award 22 new grants of $12,500 or $25,000 each for a total $300,000 to help defray the costs of translation from works in 15 languages and five continents. In fact, here’s a bright spot amid the crushing distress of “your tax dollars at work” in so many wrong places these days: since 1981, the NEA has awarded 455 fellowships to 404 translators working into English from 69 languages and 82 countries. NEA literature director Amy Stolls calls this “expanding the range of ideas and viewpoints.” And that’s how you build open doors, not walls.

Meanwhile, Vermont College of Fine Arts has announced what’s thought to be the world’s first low-residency international MFA program in creative writing and literary translation. Hong Kong author Xu Xi, a visiting faculty member, is helping to head up the new program. In a prepared statement about the new MFA, Xu is quoted, saying, “The literary world is global and writers need to broaden their perspective beyond their own borders through immersion in other cultures and languages, and through interactions with writers from other parts of the world.”

Do you know Three Percent? It’s Chat Post’s site and project, based at the University of Rochester, that’s the closest thing we have in the States to an authority on translated books. Post, always struggling for adequate resources of time and money, diligently tries to track and evaluate the work going on in this country in translation. He also publishes translation from Open Letter Books.

Do you know Three Percent? It’s Chat Post’s site and project, based at the University of Rochester, that’s the closest thing we have in the States to an authority on translated books. Post, always struggling for adequate resources of time and money, diligently tries to track and evaluate the work going on in this country in translation. He also publishes translation from Open Letter Books.

And he named the site for a guess. Over many years, it’s been estimated (no one can prove this) that US citizens’ reading lists tend to include, at best, three percent literature in translation. Although still in the anecdotal stage, there are signs of rising interest, even in the American readership, in work from other cultures.

Part of the credit goes to AmazonCrossing, the translation imprint of Amazon Publishing (that’s trade publishing, not self-publishing). AmazonCrossing has become the new powerhouse of translation, putting out far more titles per year than its closest competitor in that regard, the Dalkey Archive. And one of the things that AmazonCrossing’s editorial director, Gabriella Page-Fort, is talking about these days is that glowing connection between the political conditions of this ridiculous year and the chance to communicate with another culture.

‘This Sense of Responsibility’

Provocations graphic by Liam Walsh

“I’m feeling a lot of stress about the state of the world,” Page-Fort told me when I interviewed her earlier this fall. “I think we’re all paying closer attention to the bigger world right now than maybe we have in my lifetime. And I think that’s a huge opportunity for books in translation. The way that’s influencing AmazonCrossing is that we’re doubling down on the intention of what we’ve been doing all along, which is trying to find the stories that make people feel more similar than different. Things that make it so you can connect and see directly into the eyes of whatever today’s ‘other’ looks like.

“That’s going to come through in more diversity in terms of language and countries of origin in the books we publish. There’s an additional focus on nonfiction. We’re finding some really exciting projects of people telling their own story in their own voice. And I really do feel this sense of responsibility. Because we have this opportunity to present books to readers, to show readers the world as it is. And to bring a little bit of awareness, just through fiction.”

“That’s going to come through in more diversity in terms of language and countries of origin in the books we publish. There’s an additional focus on nonfiction. We’re finding some really exciting projects of people telling their own story in their own voice. And I really do feel this sense of responsibility. Because we have this opportunity to present books to readers, to show readers the world as it is. And to bring a little bit of awareness, just through fiction.”

One of Page-Fort’s secrets: She’s had the submission portal for AmazonCrossing translated into 14 languages. Another: she assigns translations of genre work, lots of it, not just literary work, which has been the tradition in the past. In fact, you may know some of the authors whose work in English is being translated into other markets by Crossing’s team: a two-way street. Here’s Catherine Hyde Ryan’s Ich bleibe hier, translated by Marion Plath.

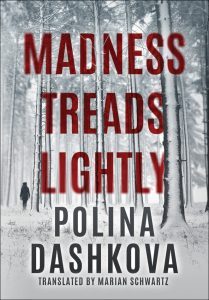

So readers who wouldn’t touch that thing by a Nobel winner from a distant land can also find Madness Treads Lightly by the Russian author Polina Dashkova, in translation by Marian Schwartz. It will scare your life out. It will also tell you “something about what it feels to be a woman and a mother” in the post-Soviet realities of modern Russia.

So readers who wouldn’t touch that thing by a Nobel winner from a distant land can also find Madness Treads Lightly by the Russian author Polina Dashkova, in translation by Marian Schwartz. It will scare your life out. It will also tell you “something about what it feels to be a woman and a mother” in the post-Soviet realities of modern Russia.

So maybe we’re starting, in the English-speaking world, to do what we should have done long ago: read more books by people with funny names.

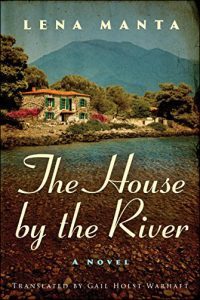

Want a recommendation? Try The House by the River by Greece’s Lena Manta, translated by Gail Holst-Warhaft. It’s a Greece you don’t know, an era you won’t recall, a deep meditation on “refuge beside a river” of generational currents and meandering relationships.

My provocation for you today is this:

Why aren’t we better about reading from other cultures, here in the United States? Is it something along the lines of that bogus old travel dodge, “Oh, I don’t need to travel overseas when we have so much here at home”? Is it purely the fear of “the other” that seems to drive some voters to follow bigots? Is it that we just don’t care about other cultures and understandings of life?

Let me know your thoughts. By the way, please join me in the international campaign to #NameTheTranslator whenever you talk or write about translated work. Translators are our brother and sister artists in the business and their work is essential to the success that many of us would like to see for effective globalized readership in the marketplace.

[coffee title=”Wish you could buy Porter a glass of Campari?” icon=”glass”]Now, thanks to tinyCoffee and PayPal, you can![/coffee]

My guess would be translated books suffer in this country for all the reasons you put forth. For my part, I’ve read more translated books in the last four years than in all the decades before. Maybe, too, it’s a fear that we’ll read the book and not “get it,” that it’ll be in some way too different for us to understand and enjoy. For me, they open the mind to all that’s universal, and, yes, all that’s a bit different, but that’s the wonder of it all. Translations are, like immigration, what make us richer. They nurture diversity of the mind. I’ve retained only a fraction of the math I learned in school, but what I HAVE retained is the ability to employ logical thinking.

Hi, Christina,

And how very well that “ability to employ logical thinking” works for you.

This is very encouraging to hear of your interest in translation. I think you point out an important note I’d left out, too — that fear of not understanding another culture’s writings. Like “Fear of Missing Out,” we could call this the Fear of Not Getting It, and it’s pretty pervasive for some, I imagine.

Because I travel internationally a good bit, I do find at times that I’m not getting it in regards to one element or another of how things work — and at times, I can find this reflected in how I handle translated work. But instead of putting me off, I find that this helps confirm the “otherness” of cultural ways and means, which can bring texture and color to life if we don’t let it scare us.

This is a wonderful line: “Translations are, like immigration, what make us richer.” Precisely, thanks for it and for your whole comment, great of you to be in touch.

Cheers and read on!

-p.

On Twitter: @Porter_Anderson

Thanks for this, Porter. Probably the most heartwarming news I got this past year, even more than the sale of my latest novel, was that translation and publication rights for The Art of Character have been sold in Spain and mainland China, and we’re pursuing similar deals in Japan, Hong Kong, and Taiwan.

I think it’s always the artists who first reach across cultural barriers. It’s just our intrinsic curiosity and openness to the new. My musical hero in this regard has always been Ry Cooder, who simply seems incapable of not reaching out to musicians from different backgrounds to collaborate.

Have a lovely Thanksgiving.

Hey, David,

Great to hear from you and congratulations on the translation sales for The Art of Character — those are two fabulous markets to be sold into because Spanish, of course, gives you access to the Latin American markets (and a large part of the US population), and China is China! May they bring you many sales and new readers, and fingers crossed for Japan, Hong Kong, and Taiwan, too — Taiwan is a marvelously avid reading market, they punch way above their population size. If your agent is looking for more action in the ASEAN region, I’m very impressed right now with Vietnam’s presence (I’m just back from our annual conference in Singapore, so that’s on my mind). They’re doing a great job, the Vietnamese, of reaching out and engaging now.

Please feel free to have your agent send me news of such rights action on your books: Porter@PublishingPerspectives.com — we do periodic updates on such news, I’d be glad to have it.

And carry on, you’re branching right out there. Good Thanksgiving to you, too (and try translating THAT holiday for the readers of Uzbekistan, lol).

Cheers,

-p.

On Twitter: @Porter_Anderson

PS. Albert Camus has taken over the avatar spot on your Twitter page. :)

Growing up in a multi-lingual society, the need for translations was common and just a casual look at our home library makes me appreciate translators. We have quite a few translations, almost all classics, from the Gitanjali to Confessions to the Spanish mystics. My husband bought the Liturgical Year–a 15 volume set by Dom Prosper Gueranger–and it’s heady thinking about the Little Flower and her sisters and mother listening to her father read from it. Talk about a family of saints reading about saints. There’s such a connection across time and space with books like these. Translator is Dom Laurence Shepherd. This is going to be a lifetime of reading. They are beautiful books.

I have enjoyed the Russian storytellers but haven’t read anything recently, so will check out Polina Dashkova. Thanks Porter. Have a happy Thanksgiving.

Interesting to hear about what’s happening in Vermont! Victoria University of Wellington (in New Zealand) offers MAs (theoretical or practical) and PhDs in literary translation, although it appears to focus on Chinese, French, German, Italian, Japanese and Spanish, since those are the languages taught by VUW’s School of Languages & Cultures.

And now I’m asking myself: what was the last thing I read in translation? Apart from the Bible, aka The Most Translated Book of All Time.

When I publish my first novel, I would be more than thrilled if it was translated and purchased in other countries. And I am eager to read about other cultures and make a point of knowing what is going on in our country and the world. My favorite Tweet and FB post is WAKE UP. The world and its people, how they are viewed and honored or abused, affects us here in the U.S. We are all connected and writers know that when they put words on the page. I’m with you, Porter. Thanks.

Porter, I’m dusting myself off from the rabbit hole I crawled into after reading your post. You reminded me that I saw a headline a week ago saying that there was a new translation of “War and Peace.” That puzzled me, because I knew that the work had multiple translators over the years, and I was curious what could have motivated a translator to dog-sled across that vast territory yet again.

But in searching it out today, I couldn’t find news of a new translation. However, I did see this site which supplied overviews of the various—including abridged versions—of translations, far greater in number than I knew:

https://ospidillo-blog.blogspot.com/2011/02/which-translation-of-war-and-peace.html

Then I learned that War and Peace translations sparked a literary skirmish:

https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=15524432

And that the New Yorker has a long and delightful account of translation swordsmanship over various texts, with stabbing wounds, including the apparently fatal one ending a long friendship between Vladimir Nabokov and Edmund Wilson:

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2005/11/07/the-translation-wars

Translating: not for sissies.

I pulled out my lovely Inner Sanctum Simon and Schuster edition of W&P, with its detailed maps of Napoleon’s travail, extensive character lists and relationships, and bloody front-matter illustration. Because I’d read a bunch of C. Garnett’s translations of Dostoyevsky, I’d for years remembered this as hers, but no, it’s a Maudes translation. (Note: during my 20s, when I was “reading the Russians” I learned how to hold my head as a heavy object and cast my eyes to the far-off distance and scratch my face in melancholy.)

Anyway, excuse the rambling—thank you for putting me in mind of the good work that translators do—and the work that people put in to tell you that a particular translation is a dullard’s work and another voiced by the angels. (Just check out the Goodreads threads on which version of W&P is the “right” one.)

I was also grateful that you sent me to my shelves to pull out a few quaint and curious volumes of forgotten lore, as Mr. Poe might opine, because there’s no small pleasure in flipping through the pages of old pals.

I strongly recommend the crime thrillers of Deon Meyer, which are translated from Afrikaans, and readily available in English speaking countries.

Also the detective mysteries of Fred Vargas, translated from the French.

The Condor Trilogies of Jin Yong (Louis Cha) are being translated into English.

Didn’t everyone in the US read The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo in translation?

Interestingly too, Americans don’t read books set in Australia either, even though they are in English (of a sort :) I write cozy mysteries set in the 1870s on the Murray River paddle steamers, but it is only Australians and Brits who read them. I was always aware that might be the case when I wrote them, as the rest of the world knows how inward looking the US is. My next series will be more generic. Shame really, as I read a huge number of books set in the US.

Torontonian Linwood Barclay sets all his novels in the US for that reason. But don’t get me started on that …

Years ago my sister (an Englishwoman) was dismissive of books in translation. “A translation can never capture the author’s intent,” she said. My wife (Swedish and multi-lingual) said, “So you choose to read books in their original language?” “Good heavens, no,” said sister mine. “I’m no good at languages!”

This was probably the first or second time they met.

Ever since then – for about 30 years now – when I’m looking for a birthday book for my sister, my wife will always suggest a title recently translated into English. I think my sister’s received a couple of dozen over the years. We like to think we’re wearing her down.

Hi, Porter. Sorry to be late to the party. Thanks for raising this important subject! I’ve always read a fair number of books in translation, but that number exploded when I started going to Toronto’s International Festival of Authors. What a wonderful world of literature is out there!

Then my Italian teacher asked me to be a guinea pig for her new translation course. Trying to create good English versions of Italian poetry and prose was challenging enough, but trying to go the other way defeated me. I have new respect for translators everywhere and am so grateful for their work.

I think the reason people in the U.S. don’t read more across cultures is that we aren’t aware of these books. Within a month of my son moving to Toronto he sent me a long list of Canadian authors I’d never heard of whom he recommended I check out. Even without a language issue, it’s hard to hear about books from other countries. When we do, people don’t seem to have a problem reading them–I’m thinking of 100 Years of Solitude, the Stieg Larsson books someone mentioned, Colette’s novels, the Russian classics.

That raises the larger issue of how we discover books. I’m guessing mostly word of mouth, reviews, maybe author events or library staff picks. School reading lists. Suggestions from booksellers (online and brick & mortar). If we can get more translated books into that supply chain, we might see higher readership and enjoy the benefits of a wider world view.