Stereotypical Perspectives

By Guest | December 11, 2015 |

Today we’re thrilled to have Kristina McMorris join us. Kristina is a New York Times and USA Today bestselling author and the recipient of more than twenty national literary awards, as well as a nomination for the IMPAC Dublin Literary Award, RWA’s RITA® Award, and a Goodreads Choice Award for Best Historical Fiction. Inspired by true personal and historical accounts, her works of fiction have been published by Kensington Books, Penguin Random House, and HarperCollins.

Today we’re thrilled to have Kristina McMorris join us. Kristina is a New York Times and USA Today bestselling author and the recipient of more than twenty national literary awards, as well as a nomination for the IMPAC Dublin Literary Award, RWA’s RITA® Award, and a Goodreads Choice Award for Best Historical Fiction. Inspired by true personal and historical accounts, her works of fiction have been published by Kensington Books, Penguin Random House, and HarperCollins.

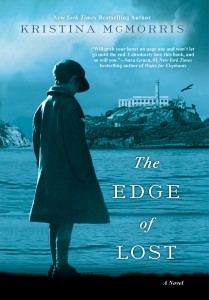

The Edge of Lost is Kristina’s fourth novel, following the widely praised Letters from Home, Bridge of Scarlet Leaves, and The Pieces We Keep, in addition to her novellas in the anthologies A Winter Wonderland and Grand Central. Prior to her writing career, she hosted weekly TV shows since age nine, including an Emmy® Award-winning program, and has been named one of Portland’s “40 Under 40” by The Business Journal.

So often, novelists are warned not to incorporate stereotypes into our characters, and yet stereotypes exist for a reason: because they’re usually based in truth. There are so many literary rules—not to mention PC guidelines—we’re afraid of breaking. I hope my post will help liberate some writers who might feel hindered in this respect.

Connect with Kristina on Facebook and Twitter.

Stereotypical Perspectives

The theme was “Asian Invasion.”

For years I had been tasked with planning an annual appreciation party thrown by my family’s company. Invitations would reveal the surprise theme each year, spurring the vast majority of our five hundred guests—from vendors and customers to politicians and journalists—to find or create suitable costumes to compete for the highly coveted first-place title. Up until then, we’d covered the Roaring 1920s, mobster-era ’40s, ’50s diner days, and disco glam of the ’70s. Sprinkled between those had been a Wild West saloon, sports pub, Vegas casino, and a French Renaissance-style masquerade ball. In various ways, culture played such a key role in those events that ultimately it didn’t feel a far stretch to move on to an Asian theme.

“Throw PC out the window! Just have fun!” we told our guests at a time when the fear of offending others had seemed at an all-time high (a miniscule level compared to now). It didn’t require explanation that the reason my family could host a party encouraging creative Asian costumes was simply this: We’re Asians. (Or half, in my case.) I suppose you could say we had an ethnic “hall pass.” And that allowed us, for a single evening, to extend that pass to others.

On event day, it was a delight to watch people pour out of their cars dressed as Chinese take-out boxes, sumo wrestlers, sushi rolls, and the stars of The King and I. My sister and I went as the Siamese twins from the film Big Fish, our dresses connected at the hip by Velcro. We laughed at ourselves, and others, entertained by the silliness of it all, despite—or perhaps due to the fact—that bits of truth had inspired those costumes.

My sister and I went as the Siamese twins from the film Big Fish, our dresses connected at the hip by Velcro. We laughed at ourselves, and others, entertained by the silliness of it all, despite—or perhaps due to the fact—that bits of truth had inspired those costumes.

With a father from Kyoto, I was raised in a house where shoes were removed in the entry, the camcorder was viewed as another member of the family, and we used chopsticks to eat rice that was perpetually being warmed in the rice cooker. There was a hierarchy established by birth order, a priority placed on bloodline, and a demand that loyalty and respect trumped all. And, naturally, bowing and karaoke were a normal part of life.

This firsthand knowledge obviously boosted my confidence while crafting characters in my second novel, Bridge of Scarlet Leaves, which largely centered on the Japanese American internment experience, as well as their classified service in the U.S. Army during WWII. I admit, I did worry on occasion that aspects of my Japanese characters might be criticized as being “stereotypical.” But when I voiced the concern to my husband, whose work entails global relations on a daily basis, he was quick to remind me that stereotypes often arise from general nuggets of truth, and I have to agree.

In no way does this mean I believe in portraying stock, cardboard cutouts who more closely resemble cartoon characters than real humans. It just means we shouldn’t be afraid of including behaviors and traditions that are commonly inherent in a character’s heritage, simply from fear of causing offense or garnering a review spatting a “cliché” label.

Of course, I’ve come to realize that this is a far easier stance to take when writing about an ethnicity for which one holds genetic claim. I imagine, by many readers of my second book, I was viewed as an expert at… well, being Japanese. Who was going to challenge me on those related details?

But then, while writing The Edge of Lost, I found myself with a cast of Irish and Italian immigrants. Yes, my family has Irish roots (whose in America doesn’t?); and granted, I was fortunate enough to study in Florence during my college years. But neither qualified me as an expert. And so, inevitably fear seeped in.

Common sense told me not to make my Irish characters speak like leprechauns with a penchant for spouting, “Top o’ the mornin’ to ya!” And my Italian characters wouldn’t spend their days singing “O Sole Mio” while hand-tossing pizza dough. Yet based on every pertinent memoir I read, more often than not, the Irish lads dreaded their strict nuns in school and had fathers with a habit of spending wages at a local pub. Similarly, the Italians related stories of the family dinner table, where wine was treated like water, mothers constantly insisted the children weren’t eating enough, fathers could be quick with tempers, and speaking over one another qualified as conversation.

I’d personally observed most of those Italian dynamics decades ago; nonetheless, when funneling them into a novel, was I overgeneralizing? Was I setting myself up for ranting emails and nasty reviews? (Oh, to mentally quiet those prospective one-star reviews.)

In the end, I decided it would be ridiculous to veer away from any and all stereotypical attributes, since many of them were indeed built upon truth. So long as I kept my characters grounded in reality and added depth to their personalities, including backstories that had shaped their lives, I could feel confident in my choices. And on occasion, I would point out to the reader the ways in which they weren’t like typical Irish or Italian families. Because, as we all know, there are always exceptions—just as every Texas rancher doesn’t wear a cowboy hat. (Then again… maybe he does!)

Once the manuscript was finished, I did share copies with an Irish reader and an Italian-American friend for last-minute feedback. That’s when the payoff felt worth the risk, for both returned with comments echoing similar sentiments: that they felt as if they’d spent time with friends and family they knew.

As a writer, could there be a greater compliment?

Have you struggled with applying stereotypical traits in your stories? Did you steer away or include them? Have you found your own way of tackling this challenge?

Terrific distinctions here, great post! I had to chuckle at your difficulties in literary/high fiction– with epic fantasy the polarity of the problem is almost reversed. There’s SO much world-building to sneak in, you NEED stereotypes of race and behavior as vital shorthand or else you’ll never inform the reader enough to get back to your characters and their choices. Where to make exceptions, that occupies all your time. Elves don’t age, Dwarves love to work in metal and jewel, Halflings make no noise: moving on!

I would say a good stereotype (well done, useful, three dimensional) is a close cousin of an archetype. And what fantasy author isn’t reaching for that?

Will, how funny that there’s such a difference between genres! I never would have thought of that perspective in fantasy, but of course it makes perfect sense. Always love learning something new. Thanks so much!

The novel I just published has three main characters, one of them an Irish actor in his mid-thirties.

I undertook him with a great deal of trepidation: my personal experience of the Irish is limited to general culture and loving the accent.

I was lucky enough to find a friend online in the same place in Ireland I had given him as a birthplace (County Galway), and she was kind enough to vet my choices and answer my questions about nouns (an easy way to distinguish English-speaking countries).

But my biggest thrill was when I received first very encouraging words while writing from a famous Irish literary author on Wattpad, where I was posting the novel during writing/editing/revising – and his wonderful review after he read the whole thing.

Phew! Dodged the bullet there. I kept the touch very light, gave Andrew a single verbal tag, and worked on giving the flavor of the accent by word order and word choice rather than leprechaun spellings.

But it was a constant worry, and I am glad to be out of having to consider every word.

The short story prequel to the novel has been featured on Wattpad, and has 58.9K reads – and is significantly more Irish (I had a lot more help with nouns for it). I could not keep that up for a whole novel, and there are good reasons why he has become more cosmopolitan in his speech. That one had me quaking.

You nailed it with ‘So long as I kept my characters grounded in reality and added depth to their personalities, including backstories that had shaped their lives’

Writing is WORK. I wouldn’t have it any other way.

I’m absolutely with you on the brogue, Alicia! It’s hard to top such a charming accent. Like you, I feel very lucky to have found someone from the same birthplace as my character who was willing to lend her time and keen reading eyes to help ensure authenticity! Resources like that are truly a treasure.

Best wishes with your new novel and prequel!

As a reader I find that stock characters can be comfortably familiar but also dull and predictable. And I dislike when stereotypes become caricatures. I like your advice to keep characters “grounded in reality and add depth to their personalities, including backstories that had shaped their lives…” So, you enlarged them in some way? Or broke the standard expectations? That makes sense. I hear you saying to use more detail? Thought-provoking post. Thank you, Kristina.

I see Will’s remarks about stereotype and archetype being close cousins. I had to think about that for a moment. I don’t see them as similar. I think more negatively of a stereotype, whereas an archtype has a positive image, more of an ideal pattern, possessing something original. To me these two terms are more opposite than cousins.

Hi, Paula! Yes, I would definitely say details are key. From those details the character becomes a real person the reader can root for (or against). I’m so glad the post was helpful!

Funny, in your description of the Italian family, I saw my own boisterous Indian family. There are some universal truths. And I agree that stereotypes arise from the observation. I joke that my American husband’s family seems to run on Indian Standard Time. And of course, in every joke, there’s an element of truth.

Congratulations on your new book!!! It looks delightful.

That’s such a good point, Vijaya! There are definitely universal truths when it comes to family dynamics. To me, this seems even more the case with immigrant families, no matter the ethnicity, as they struggle with fitting into their new country while also retaining elements from their homeland and cultural upbringing. And all the while, their children strive to be “normal” American kids. As I’m sure you know! :)

I found so many commonalities between my Japanese father’s traits and those described in Italian-American memoirs that I was able to infuse many of my own personal stories into the novel — which is always fun.

Thanks for the comment and kind wishes!

At our recent Women’s Fiction Writers Association retreat, I ran a discussion on diversity in literature. And the one thing that we did struggle with as we talked was how to present our diverse characters, yet at the same time not stereotype them. Once again as writers we must rely on creative measures to bring our characters to life on the page, but not shove them into some predictable corner. And this can apply to all aspects of the characters we draw–their looks, speech, backgrounds, etc. Thanks for your post.

I totally agree with you, Beth! Beyond behavior and backgrounds, physical descriptions and speech can be just as varied regardless of a person’s (or character’s) upbringing. In relation to my post, not every Irish person is going to be pale skinned with freckles and red hair. But then, those traits do exist as well.

Thanks for the comment! It’s great to know that writers’ groups like yours are addressing a similar topic through open discussions!

Thank you for sharing this – great post. I think the problem with stereotypes isn’t that many may arise from a nugget of truth, but that the stereotype is often the only or the most pervasive version of a set of people that some groups ever see. When that’s the case, the stereotype becomes the only reality for large swaths of people.

One of the ways to work within that challenge is to invite more than one type of person to the table when you’re writing (the table being your novels.) A timid Chinese girlfriend who’s the only Asian woman in an entire story, feeds into stereotype. A black male character who’s a thug and is the only black male or person of color in an entire novel, feeds into stereotype. But when you’ve set a diverse table with more than one person from a group has been invited to dine, then you reduce the risk of being called out for writing stereotypical characters.

Having friends from each group share their opinions on what you’ve written is a great idea – with the caveat that that person doesn’t (and can’t) speak for an entire group of people.

It’s not easy, and I don’t think as writers we’ll be able to please everybody, but I think it’s worth the effort.

Such great input, Grace. I couldn’t agree with you more regarding the consequences of portraying only stereotyped characters representing an entire group of people. In films and TV, it obviously happens much too often. It’s the lazy choice, in my opinion.

In contrast, the challenge I personally encountered while writing my last novel was that I became so afraid of touching upon any traits that could be deemed stereotypical that I was compromising the authenticity of my characters. And allowing fear to dictate which words do or don’t make it to the page is never a great writing experience.

To your point, the more educated and openminded we are about other cultures, groups, and people who are just plain different than ourselves, the more well-rounded our characters will become, as well.

I was born and grew up in Phoenix. (Yes. The one that matters, folks from up there in Oregon.)

And there was something I didn’t understand about Asian people until I was an adult, married, with children.

I went to school with a number of Chinese kids. I had this crush on one girs. Talk about sterotypical–smart, played the piano well, wore glasses, and could make me sigh just by talking to me.

But I didn’t know or go to school with any Japanese kids. I knew there were quite a few Japanese families in the Phoenix area. I would see the Japanese Free Methodist Church out at Lateral 16, now called 43rd Ave., and Indian School Road.

The reason I didn’t know any Japanese kids was because they lived away from city center, out near the agriculature fields. Their families were farmers, flower growers (people still talk about the old time Japanese flower gardens, a spring-time treat).

To me, Asian kids were among the elite. Their families were huge farm owners, store owners, restaurant owners, and successful merchants of all types.

Even as an adult, for many years, I would be surprised to go to Los Angeles, San Francisco, Portland, Seattle, and see Asian men and women who were hotel employees carrying luggage, or driving cabs, or busing tables, or doing regular jobs.

Talk about sterotyping. (By the way, if anyone knows Doris. Have her give me a call. I’ll bet she’s still cute.)

Well… if you insist on viewing my relatives as elite, I won’t argue. Ha.

Honestly I feel really fortunate that, although my family had little means when I was a kid, my father would use his mileage from business trips to take our family on one big trip a year — to places like Costa Rica, Thailand, and New Zealand. We were given an incredible gift of seeing how people lived in other parts of the world, and usually made us realize just how lucky we truly were. I think that kind of exposure — which many people get through even the magic of books! — helps dispel those misconceptions.

I’ll tell Doris you said hi! :)

Thanks for this. The MS my agent and I are planning to shop early next year has about a half white, half black cast. For some of the WASPy characters, I could draw on my own experience of being brought up with a German Protestant ethic–work hard, mind your own business (don’t protest things, don’t fight battles that aren’t yours, etc.), don’t complain, everything you got you earned, don’t challenge the status quo. Everything negative (and positive) about those characters I can back up with my own experience.

But for my African American characters (in three time periods–1860s, 1960s, and present day) I worked hard to present well-rounded people. They don’t all speak the same and they don’t all hold the same views on life or on the racial politics of their day. But absolutely there is some stereotypical stuff for both the white characters and the black characters. I did extensive research, drew from my experience talking to black friends, and I had three black friends read early drafts, specifically to look for issues and to help me make voices authentic. One reader even suggested I ADD something that I thought was very stereotypical and had avoided!

All that background work and “vetting” and I’m still sure that there will be people who complain (and probably there will be people complaining on behalf of others who may not actually find anything to complain about, as is sometimes the case in our very sensitive society). But one thing that helps me not get too worked up and nervous about it is that I know I’ve written each character with the best of intentions and a heart turned toward the truth of the story. You can’t please everyone, and some people don’t want to be pleased by anything because they thrive on righteous indignation (which knows no race, religion, or ethnicity).

“I know I’ve written each character with the best of intentions and a heart turned toward the truth of the story.” I love this, Erin — along with the rest of your thoughtful comment. It’s great to know we were in a similar boat. As I mentioned in a reply above, having those honest friends and readers who are willing to help guide you toward authenticity is such a gift.

Best wishes with your subs in the new year! I hope we hear about a wonderful sale very soon!

Erin, I love that you’re writing a book with a diverse cast of characters. And yes, you might find some people who have issues with some of your portrayals, because PEOPLE (LOL), but people have issues with people outside of the pages of books too. That is reality. In a post I wrote about diversity in writing for WU I mentioned a friend who was offended that one of the lead characters in a show we both liked was a black man who was sort of a daddy’s boy. I pointed out that the other two leads were a womanizer who had a hard time holding down a job, and a gambling addict. Which vice was worse? We’ve got to be open to seeing real life portrayals of POC in books and film or we’re always going to be seen as sidekicks and secondary characters. I’m glad you chose to portray a wide variety of personalities and traits among your characters, and I’m sure that with the research and effort you’ve put in at being authentic, that that will come through in your characterizations.

I think Grace hits the most important note:

I think the problem with stereotypes isn’t that many may arise from a nugget of truth, but that the stereotype is often the only or the most pervasive version of a set of people that some groups ever see.

I think it’s easy for any of us to fall back on stereotype when we try to write “other” in our stories. Sure, characters of any particular group might share some similar characteristics, but above all, we must give them roundedness. If we’re going to have even a minor character reflect “other”, then what little we give that character shouldn’t fall back on that stereotype. Shared experiences? Sure.. and really, I feel like that is the way we should look at it instead of saying it’s okay that some of our characters follow stereotype. I don’t want to let myself off the hook in that way.

I agree, Janet. As I mention in my post, I’m not encouraging others to fall back on stock characters, which to me is lazy writing — just not to be so afraid of including elements common to a particular culture, for fear of being criticized as stereotyping, and thus sacrifice authenticity as a result.

Hi, Kristina:

Theophrastus, a student of Aristotle, wrote a book titled MORAL TYPES, in which he described in exacting detail a variety of stock characters that became the mold for writers for centuries, all the way to Thackeray and Dickens and beyond: the Flatterer, the Backbiter, the Gossip, etc.

These all seem acceptable and useful at times (if limited — like Paula points out, they’re highly predictable in what they do and say).

But when we turn toward stereotypes that pretend to reflect a certain identifiable class of real individuals, we can find ourselves in quicksand.

You’ve pointed out one great way to get out of the muck: detail. Every individual inherits a great many “stock” traits simply by being part of a subculture and wanting to blend in. One great way to break from the stereotype is then to ask: how did this character make an attempt NOT to blend in? Some will do very little, being afraid to stand out. Others will toss away everything, “leaving home” for the same of an utterly unique individuality.

I think one great way to avoid stereotype is to ask that simple question: What did my character do so as to NOT fit in?

Fascinating post. Thanks.

I love your insight here, David. In literature, as with film and other forms of storytelling, the characters that seem to most captivate readers and audiences are indeed so often the ones who go against the grain. (Since Hunger Games was on TV last night, Katniss Everdeen immediately comes to mind.)

I think your question about intentionally breaking from the norm (and thus, stereotype) is a great one to ask!

My (now-ex) wife and I lived in Los Angeles in the 1990s. We befriended an elderly Caucasian lady, a widow. Before WWII she had married a Japanese man, and they lived in the Los Angeles area.

He was “called” to the internment camps and Estelle Ishigo decided to accompany him. She made many sketches and drawings and published them after the war in a book, _Lone Heart Mountain_.

I’m afraid we lost contact with her after several years. My wife had stored many of her original sketches and got them to the Japanese-American society.

Yes, we could have spies and enemy agents among us. However, you won’t catch them with ethnic bigotry.

I actually own Estelle’s book of sketches, Bruce! I bought it while researching for Bridge of Scarlet Leaves, since the premise of my story was inspired by the 200 non-Japanese spouses who lived in the camps voluntarily, just like Estelle. How wonderful that you became friends with such a courageous woman.

My last novel and my current manuscript both have a very stereotypical ‘geek guy’ as a secondary character and their scenes and dialogue have been by far the most fun (and easiest) to write!

Where I would strongly avoid stereotypes are as main characters.

I can talk all day about ethnic stereotypes. As someone of Spanish, Mexican Indian and German extraction, I get it from all sides. Whereas people used to ask me where I was born, now they assume I only speak Spanish. I was born in Dallas, Texas, like my father; in fact, on his side of the family, we’ve been in Texas since the 1580s. When I tell people my mother was born in México, some have asked if she has a green card. She was already a U.S. citizen, though, because her father was born in Michigan. That’s where the German side comes into play. Growing up, people of European ethnicity were the ones who most often made racist comments towards me. Today it’s other Hispanics. Even African-Americans are more likely to make such derogatory remarks than Anglos, Irish, etc. Does that mean we’ve all come full circle?

When my mother was in school in the 1940s (after her father moved the family to Dallas), other kids often called her half-breed, upon learning she was German / Mexican. She had the habit of rearranging the furniture on their faces in response. Some 20 years ago one of my first cousins on my father’s side married an Anglo man. Shortly after they had their son, my cousin jokingly referred to the baby as a half-breed at a family Christmas gathering. My mother didn’t think it was funny and told my cousin why; explaining what she had gone through as a child of mixed heritage herself. Some stereotypes linger too long.

Great post. I’m struggling with this as I write a novel from 2 POV– one white (like me) and one African American (obviously not me!). But I loved what you said about creating authentic characters with authentic backstories. That seems to be key here. Will reread this post again. Thanks.

I once wrote a short story about a boy whose family immigrated to California from Mexico. When I described his mother and father, I borrowed traits from the parents of the many Hispanic classmates I had growing up in SoCal.

A friend read the draft and said, “You can’t give the father a salt-and-pepper mustache. It’s too stereotypical. Take it out.”

I said, “But I based that character on a real person I met, and he had a salt-and-pepper mustache.”

He said, “Readers won’t know you based him on a real person. They’ll think you’re just being racist.”

Miffed, I said, “What on earth is ‘racist’ about a salt-and-pepper mustache? Your own dad has a salt-and-pepper mustache! If I wrote about your dad, would you ask me to edit out his mustache so no one will think I’m racist?”

“No, because my dad is Caucasian. It’s fine for a Caucasian man to have a salt-and-pepper mustache. But a man from Mexico can’t have a salt-and-pepper mustache. Take it out.”

Everyone knows broad generalizations about cultures can be demeaning, but PC gets ridiculous when we have to avoid innocent character traits so audiences won’t think we’re racist. For example, I have a Chinese aunt who’s a genuinely terrible driver. If I wrote about a white man who’s a terrible driver, people would think it’s a funny quirk. But If I wrote about a Chinese woman who’s a terrible driver, the backlash would be swift and merciless.

I think stereotypes are a problem when a fictional person is nothing but a stereotype–when authors substitute “culture” for “character.” He’s the big Italian guy who speaks loudly and waves his hands around a lot. She’s the sweet Southern gal who wears cowboy boots and speaks in countryisms. That’s all here is to them.

But as you said, Kristina, we shouldn’t be afraid of offense if we’re making authentic, well-rounded characters. There’s nothing wrong with portraying people whose looks and behavior are influenced by their heritage, as long as their heritage isn’t all they are.

Great post.

I like to use stereotypes for passers-by and minor characters to help the reader have an instant image of that character without me going into any detail describing them or their behavior. And I also use stereotypes for villains — not to create them (that’d be boring) but to create a quick first impression upon which I can introduce a twist and humanize them. Of course, for very minor villains (such as the face-less bad guys trying to kill the protagonist before she reaches the Master bad guy) I also use some stereotypical traits to “short-cut” on their screen time.