Happily Ever After

By Dave King | November 19, 2024 |

I’m a sucker for happy endings.

I’ve written before, though, that a lot of writers tend to shy away from them because they can easily degenerate into cliches. When the guys in the white hats always win and the guys in the black hats routinely go down in flames, endings start to get shallow and predictable. To avoid this, we get stories in which either nothing happens – stories that are more about creating character than watching character develop toward a climax – or where what happens to the characters is just the result of random, generally cruel fate.

I don’t buy that your only choice is between shallow, black-and-white morality and a descent into ennui and meaninglessness. Instead, I think we need to take a deeper look at where happy endings come from and what they mean. And a good place to start is the Middle Ages.

Happy endings, at their heart, are about justice. Good characters end well and evil ones end badly. But the medieval sense of justice runs deeper than the modern business of obeying the rules and making sure people who don’t obey the rules suffer. For them justice was based on the idea that any system – a person, a family, a community, a society, a nation – has a built-in structure to it, a way that it’s supposed to work. When you make choices that support that structure – letting go of a grudge to make way for forgiveness, supporting laws that protect vulnerable people from exploitation — you’re being just. When you work to break those structures down, you’re not. So according to medieval justice, stopping to let someone make a left turn to untie a knot in traffic is a just act. Picking up a shopping cart from the middle of the parking lot and returning it to the trolley is a just act. You’ve made a system, however small, work more the way it was intended.

The choices you make to support or break systems have consequences. Good people generally tend to do well because they are part of a healthier system. When evil people end badly, it’s not because some punishment’s been imposed from outside. Systems that break down tend to hurt the people that break them. To use a mechanical analogy (because, yes, I am a car geek), when you never change the oil in your engine, the engine isn’t punishing you by throwing a rod. There’s just a natural connection between clean oil and engine health.

You can see this connection between choices and consequences in Dante’s Inferno – or if you don’t have the patience for medieval Italian poetry, check out Larry Niven and Jerry Pournelle’s updated adaptation. The Inferno is renowned for the often gruesome punishments meted out to various types of sinners. But those punishments are always the direct (if graphic) result of the choices those sinners made in life.

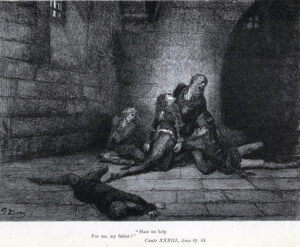

In the circle of the betrayers, for instance, we meet Ugolino della Gherardesca and Archbishop Ruggieri degli Ubaldini. The real life Ugolio had been the leader of Pisa but betrayed the city to its enemies more than once. In one of the betrayals, Archbishop Ruggieri’s nephew was killed. So when the Archbishop captured Ugolino, he locked him in a tower with his family and literally threw away the keys, leaving Ugolino to starve. (See the Dore illustration above, courtesy of Rutger Vos.) According to Dante, Ugolino’s children died first, but before they did, they begged their father to eat them to keep himself alive. Which he did.

Yes, ew.

It get ewier, I’m afraid. Dante has both Ugolino and Ruggieri locked in the ice of the circle of betrayers, with Ugolino spending eternity gnawing on Ruggieri’s brains. But note that both punishments are directly related to how the choices they made in life broke down the systems around them. It’s inherent in leadership that you not betray the people you’re leading. It’s also inherent in the spiritual leadership a bishopric represents that you not force others to commit unspeakable sins.

You see this connection at all levels of the Inferno. People who surrendered to lust spend eternity being blown around by whirlwinds. Clergy who sold positions within the church to the highest bidder spend eternity trudging around in church robes made of lead. These punishments aren’t just macabre jokes on God’s part – the eternal Mikkado making the punishment fit the crime. These people broke their own humanity and the systems around them in specific ways. They chose to become broken people. The punishments only reveal who they have decided to be. As C. S. Lewis put in in The Great Divorce, the gates of hell are locked from the inside.

You also see this in Dante’s Purgatorio, which doesn’t get read quite as often as the Inferno. It’s nothing like the purgatory James Joyce railed against in Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man – the same punishments as in hell, just not for eternity. In Dante, the residents of purgatory spend their time, not suffering, but contemplating the meaning of various sins. The point is that their humanity is damaged but not as irreparably broken as with the inhabitants of the Inferno. They’re there to heal. Not to pay a price to get into heaven, but to become the kind of people who would be comfortable living there.

So, how do we bring all this medieval metaphysics back to writing? Well, the first step toward finding happy endings is to delve deeply into your characters’ choices, to understand who the are and why they choose to do what they do. Then ask yourself, what about those choices has broken or healed something, either within your character, your character’s family, your character’s business, your character’s world. Follow that brokenness or healing through to its natural conclusion, and you will have found your ending.

Note that, while this approach does let you find natural, organic happy endings that arise out of your characters, it also leaves room for unhappy endings that don’t depend on life being inherently meaningless. Remember that systems that either break down or heal exist on a lot of different levels. So in the classic tragedy, Romeo and Juliet, the star-crossed lovers are not themselves broken, but their society at large is. It’s ancient grudges and stubborn pride that keep the Capulets and Montagues at each others’ throats. When the two innocent lovers get caught up in that larger brokenness, things don’t end well.

Understand, I’m not advocating one way or another for the theology or metaphysics behind heaven and hell. But the insights that Dante and C. S. Lewis provide into how characters and societies work apply whether or not you agree with them. They also force you to think about how people, families, and societies are intended to work and how they can be made to work better. And that can make you not only a stronger writer, but a better person.

Beautifully written and thoroughly enjoyed. Thank you, Dave.

Well, thank you, Veronica.

Hi David, you educated me early in the morning…and have me wondering how some of your words might not only apply to my writing, but also to living itself. We live in such a vicarious word…novels, dramas, films…but also real life proceeding at such a fast pace it is difficult to break it all down, to see, to find if there is some overall point that we should be getting. Evil still exists. How do we deal with it, and when writing a novel, how do we proceed to bring the story back to some equilibrium? Certainly not like Dante did, but in ways that makes a statement, yet also keeps the reader reading. Thanks for your ideas.

Hey, Beth,

“Equilibrium” is a good word. To say that actions don’t have consequences — that how we live doesn’t depend on who we choose to be — is to deny that there is an underlying organization to life.

I’ve read that this is one reason mysteries are so popular. The underlying organization is pretty basic — murder is bad, the law says so — but there is a satisfaction in seeing that organization broken, then put back together by the detective. I’m arguing that the principle applies in other areas and in subtler ways.

“The law says so” — because at its best, the law codifies the values of the society that creates it, that is, the social structure you talk about.

Nice piece. Thanks.

It’s true that the best laws do help keep society on an even keel. But the kind of justice I’m talking about extends beyond the legal system into nearly all walks of life.

Hello Dave. As usual, your post today makes use of thoughtful material from literature and/or history. I taught Inferno years ago, so I understand what you’re saying about justice. But for me, happy endings escape being simple-minded cliches by being hard-earned. You don’t get to happy without flaws, disappointments, near-misses. If the writer creates a character that readers see sympathetically, especially when the character seems on the receiving end of injustice in one or more of its many forms, that character’s happy ending will satisfy both the character and the reader.

Dear Barry,

You’re right that protagonists have to struggle in order to achieve a plausible happy ending. It’s not satisfying to simply hand good things to your characters. But I was looking at this from a slightly different, more inclusive angle. After all, characters in stories that are based on the inherent meaninglessness of life also struggle. Their struggles are simply unconnected to what happens to them in the end. They fight and overcome, then life slaps them down anyway.

Dave, after answering your questions whether the protagonist’s choices has broken or healed something, either within your character (family, business or world), I followed that brokenness or healing to its natural conclusion, and I have a happy ending. However, the protagonist says…for now. Life doesn’t stop there at happy! It goes on and answers the same questions, again & again. Thanks for always making me think about my writing process! 📚🎶 Christine

Dave, I loved this post so much. I’m a sucker for happy endings too because that’s what feels right–it’s what we’re made for. Amen to Justice. In my historical, my villain is never punished for his evil deeds by civil society because he has too much power. I wrestled with this so much because I wanted him to suffer but it wouldn’t have been realistic. But I placed my MC and her family in a safe place. With time they will be able to forgive. It frees them to have a happy life. The best revenge really! My story is only a slice–a year in their lives. My MC will go on to have a life full of love, whereas my villain will be empty despite his wealth and power. He’s the kind of person who uses people. He has chosen not to love, rather exploit. Whenever justice in this world fails, I can be sure that there’s Divine Justice. Thank you for this most illuminating post.

I have heard it said that the worst punishment for evil people is that they have to be themselves.

Thanks for this thought-provoking column. I am approaching the end of my very long (probably too long for publication!) WIP, and I am struggling with to find an ending for these characters that is both realistic and satisfying ending, without everyone sitting around in a circle confessing and forgiving each other, like participants in a 1970’s therapy marathon. But,, Dave, I object to your characterization of novels with and without “happy” endings in the first paragraph: “….we get stories in which either nothing happens – stories that are more about creating character than watching character develop toward a climax – or where what happens to the characters is just the result of random, generally cruel fate.” That is an extremely simplistic dichotomy: many thoughtful books with unhappy endings follow strong story and character development arcs. I just finished reading, for the first time, Rebecca Makai’s “The Great Believers.” True, one of the WP’s has an ambiguous but hopeful reunion with her estranged daughter (somewhat unbelievably, in my opinion), but the principle story is nothing but tragic, and, unfortunately, true to history. It certainly isn’t light reading for those times you want to escape, but it’s a spellbinding page-turner, and the tragedy is not simply random, cruel fate. Just one outstanding example.

Rats! “… one of the VP’s….” Not WP’s, whatever they are.

Hey, Grumpy,

I’m glad you liked the article, and I hope it helps you find an ending for the current WIP.

I’m not sure the dichotomy is a clear as it seems. I’d say that the ending of The Great Believers was just, if not entirely happy. Both Yale and Fiona’s lives are upended by the AIDS epidemic, which seriously broke the gay community of the eighties — that, and the homophobia of the response to it. Yale’s partner gets AIDS because of his own jealousy — a form of brokenness — and Yale gets it from despair. Yale’s death also breaks Fiona’s relationship with Claire. And, you’re right, there is a sort of reconciliation there, which (along with the gallery show at the end) is probably as happy an ending as is available to them. But the ending is dependent on the choices the characters have made.

What I was talking about in the article I’d linked to in the first paragraph (“Displeasure Reading” — https://staging-writerunboxed.kinsta.cloud/2019/09/17/displeasure-reading/) was about books like Cormack McCarthy’s All the Pretty Horses (which I was never able to finish) and similar books, where characters simply suffer in ways that have nothing to do with who they are. Even then, I acknowledged that some people appreciate this sort of writing — I read McCarthy because he was recommended by a friend.

As I always tell clients, my opinions are informed, but they’re still opinions. Your mileage may vary.

“Viewpoint characters” — aiyee.

Good post, Dave. Reminds me of Oscar Wilde’s skewering of popular fiction in The Importance of Being Earnest:

MISS PRISM. Do not speak slightingly of the three-volume novel, Cecily. I wrote one myself in earlier days.

CECILY. Did you really, Miss Prism? How wonderfully clever you are! I hope it did not end happily? I don’t like novels that end happily. They depress me so much.

MISS PRISM. The good ended happily, and the bad unhappily. That is what Fiction means.

A lovely example, and thanks, Christine.