A Tale of Two How-Tos

By Keith Cronin | November 15, 2024 |

As a connoisseur of writing how-tos (and yes, I had to look up how to spell connoisseur – and okay, “addict” might be a more accurate word), I have read a TON of them. And while I find valuable nuggets in nearly all of these books, lately I’ve noticed that many recent writing how-tos are essentially sharing slightly different flavors of some very similar core information.

So when I encounter a book about writing that offers some new (to me, at least) ways of looking at the craft, I sit up and take notice. My gushing ode to Chuck Palahniuk’s Consider This in this 2020 post is an example.

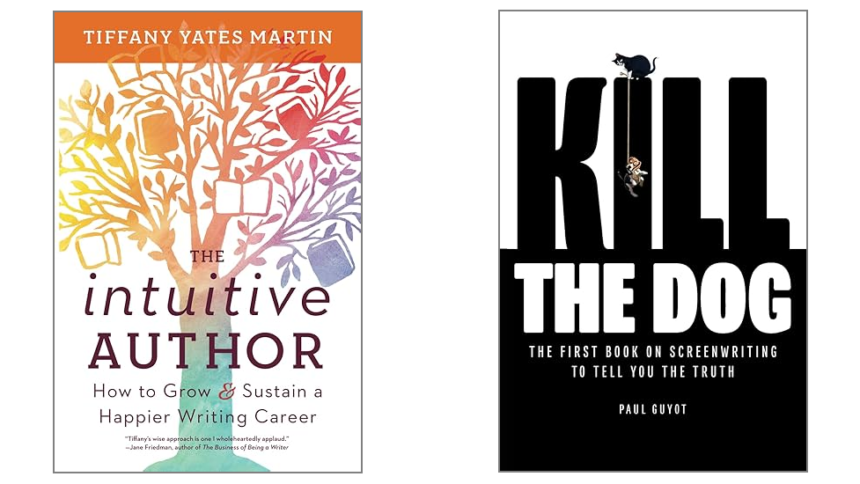

I just finished reading another such departure from mainstream writing how-tos: The Intuitive Author, by WU’s own Tiffany Yates Martin, who, in addition to being a wonderful writer and editor, is also an insanely good teacher and public speaker. Seriously, if you ever have the opportunity to attend one of Tiffany’s sessions or events, take it. And if you’re an author who speaks at literary conferences, trust me: you do NOT want to follow Tiffany. She’s that good.

Having seen Tiffany’s amazing presentation on backstory at WU’s brilliant 2022 OnCon, I knew what an extraordinary editorial mind she has, and how good she is at getting under the hood to amp up and improve your writing at multiple levels. So with The Intuitive Author, I guess I was expecting a book full of deep analysis into the mechanics of writing, along with some sophisticated editorial techniques. Instead, much of the analysis she offers in the book leans more towards the psychology and strategy involved in pursuing – and ideally, enjoying – the life of a writer.

I quickly realized I was not reading The Average Writing How-To, and I dove into the book with my curiosity piqued. (And yes, I had to double-check whether it was “piqued” or “peaked.” Got it right the first time – yay! Hey, it’s the small victories. But I digress…)

In short, The Intuitive Author is filled with insights and perspectives quite unlike those offered in the vast majority of writing how-tos currently on the market. And reading Tiffany’s book made me think about another writing how-to I’d recently read that takes a pretty big departure from most conventional writing wisdom: the provocatively titled Kill the Dog: The First Book on Screenwriting to Tell You the Truth, by author and screenwriter Paul Guyot.

What does this Guyot dude have against dogs, anyway?

Nothing, actually. Instead, the animal Guyot truly hates – and is taking a not-at-all thinly veiled swipe at – is the cat. Specifically, the cat in the well-known “Save the Cat!” series created by the late Blake Snyder.

If you’re not familiar, Snyder’s initial Save the Cat! book (STC to the cool kids) burst onto the scene in 2005 with a VERY structured set of templates for storytelling, which he reverse-engineered from studying many successful movie scripts. Targeted at aspiring screenwriters, Snyder’s methodology offered a compelling framework for them to adopt and adapt in their own storytelling. Novelists soon took note, and the book became quite popular and spawned a series of STC books that has continued even after Snyder’s untimely death in 2009.

Full disclosure: I like most of the Save The Cat! books. A lot. So I was intrigued when Amazon’s algorithm placed Guyot’s intentionally confrontational Kill the Dog at the top of my “you might like this book” feed one day.

Getting snide with Snyder

Given its title, I was expecting Guyot’s book to be… well, somewhat contrarian. And he doesn’t disappoint. From the opening pages, Guyot makes no bones about his scorn for Snyder’s body of work. But he does so from an angle I hadn’t anticipated. Historically, much of the popular criticism leveled at the STC series – and to be fair, at pretty much ALL methodologies built around a specific writing structure, whether it be Joseph Campbell’s hero’s journey (or Chris Vogler’s variation), Syd Field’s three-act structure, Michael Hauge’s six-stage plot structure, etc. – is that they are all ultimately dictating a FORMULA for creative writers to use. Which, one must admit, sounds anything but creative. And to be clear, Guyot does attack the STC approach for being formulaic.

But Guyot has another bone to pick with Snyder. And this time, it’s personal.

Guyot’s biggest complaint about Snyder – and indeed, about nearly every other well-known screenwriting how-to – is that these books are seldom written by working professional screenwriters. This is a repeated – and I do mean repeated – point Guyot makes throughout KTD (hey, if Snyder can have STC, let’s give this guy his own acronym), asserting that the vast majority of screenwriting “gurus” out there are NOT working professional screenwriters. Sure, some of them may have sold a script or two, but – according to Guyot – almost none of them are actually earning a living at the profession they purport to be able to teach to others.

By contrast, Guyot has been earning a living as a screenwriter since 1999, with a long list of episodes of Judging Amy, Leverage and The Librarians to his credit, as well as multiple episodes of Felicity, NCIS: New Orleans, and more.

As you may have inferred, Guyot gets pretty heavy-handed in his criticism of both Snyder and the entire industry that has grown like a virus to cater to the ambitions (and sometimes, gullibility) of aspiring screenwriters. Not content with attacking Snyder and other how-to authors, Guyot also takes shots at the many other “industry experts” who prey on inexperienced screenwriters, promoting themselves with puffed-up, self-assigned titles like script doctors, professional readers, story experts, and so on.

It’s on TikTok, so it must be true, right?

It’s the writing, stupid.

While the vast majority of books about screenwriting focus primarily on story structure (as well as the many VERY fussy formatting rules that Hollywood scripts are expected to adhere to), Guyot maintains that these books fail to point out the main thing that makes a script sell: the writing.

Not the correct page count, not the meticulous formatting, not the number and location of “story beats,” and – to my surprise – not even the plot. But the writing itself.

He credits William Goldman with establishing that trend, with his screenplay for Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, which would go on to win the Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay in 1969. If Goldman’s name sounds familiar, it’s because he was both a successful screenwriter AND novelist, with movie credits including All the President’s Men, The Stepford Wives, Marathon Man, A Bridge Too Far, Chaplin, Maverick and more; along with novels ranging from Marathon Man to, wait for it… The Princess Bride.

Obviously this Goldman guy can write, but how did a single screenplay change Hollywood? To quote Guyot:

“He wrote it in his Voice, his way, without thought to format, ‘structure,’ or the way all other screenplays looked and read at the time. He spoke to the reader, he described things we don’t see onscreen, he used language and syntax and turns of phrase to make THE READ as enjoyable as possible.

…

Every great script after it, from The Godfather to Pulp Fiction to Michael Clayton to Everything Everywhere All at Once has been influenced by Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid.”

As a result of Goldman’s breakout success with Butch and Sundance, Guyot maintains, “The screenwriter’s Voice became the hot ticket in Hollywood.”

And it’s in talking about Voice (a word the author capitalizes throughout KTD) that Guyot’s book truly finds its stride. This is the first screenwriting book I’ve seen that encourages writers NOT to focus so much on conforming – whether it be to structure, or formatting rules – but to finding, developing and using their own unique Voice.

So what is Voice? Here’s Guyot’s definition:

“Voice is the distinctive qualities of your own creative personality expressed on the page, including your turn of phrase, syntax, punctuation, character development, and even formatting.”

Where KTD really excels is in sharing Guyot’s love and reverence for truly good writing. He offers a variety of script excerpts from well-known films, and I’ll confess I was quite surprised to see just how much personality and individuality a writer can inject into a screenplay. In the end, Guyot succeeded in convincing me that it really IS the writing that makes a script sell. And he repeatedly calls on the reader to aim high creatively, making his book stand out among all the how-tos that focus far more on the seemingly countless rules that aspiring screenwriters are told to obey to the letter.

To sum things up, Kill the Dog is definitely heavy on the ranting, and there’s a bitterness that bubbles up to the surface a little too frequently. I submit that KTD would be far more effective with about a 30% reduction in complaints, self-indulgence and negativity. But looking past the ranting, I found some true gems of insight I’ve not seen expressed before, making me glad I bought Guyot’s book.

TL;DR version? Let’s say… three-and-a-half stars.

And now for something completely different

In contrast to KTD’s often complainy tone, Tiffany Yates Martin’s The Intuitive Author is a consistently positive read. While Tiffany does explore some of the negative emotions and experiences an author is likely to deal with – even offering some highly personal and hard-earned life lessons, along with some industry horror stories – there is never a note of the bitterness that underscores much of KTD. Nor is there any of Guyot’s apparent ill will for dogs; on the contrary, Tiffany’s book is peppered with some utterly delightful anecdotes (and photos!) featuring her wonderful dogs. Speaking of which, this is Gavin. You’ll like Gavin.

Photo by Evan Wolfe

In looking for a single word to describe the tone of TIA (because hey, why should Snyder and Guyot get all the cool acronyms?), I’ve landed on nurturing. Part life coach, part therapist, part seasoned industry pro, Tiffany has assembled a book aimed at providing emotional, psychological and strategic support to authors at any stage of their careers.

And talk about Voice – she’s got it! Tiffany writes in a conversational, witty and engaging tone that simultaneously carries the gravitas of her three decades in the publishing industry, while still maintaining the comfort and candor of a face-to-face chat with a trusted friend. Early in the book, Tiffany says her approach is essentially, “Come into my living room and let’s talk writing,” and that’s exactly how reading TIA feels. Despite being WU colleagues, I have never met or spoken with Tiffany, although we’ve exchanged some very nice emails over the past couple of years. But after reading TIA, I feel I do know Tiffany, and she’s definitely my kind of people.

Throughout the book, she offers actionable advice and methodologies for addressing a plethora of challenges that all writers are likely to face, like rejection, impostor syndrome, procrastination, criticism, perfectionism, information overload, comparison, competition, writer’s block, and more.

This time it’s personal

And Tifanny’s not merely spouting abstract theories; instead, TIA is filled with many personal – sometimes very personal – examples and anecdotes. In this age of social media, many authors feel compelled to maintain a relentlessly positive front, never admitting to any failures, speed bumps or other flaws in their perfect InstaLives. Not Tiffany. She is not afraid to share the lows along with the highs, but the result is very validating for the reader, letting them know they’re not alone in finding that this whole writing life can be kinda hard.

But Tiffany delivers far more than mere commiseration and empathy. Instead, she offers actionable advice. Using her gift for analytical thinking, she gives readers pragmatic real-world techniques to explore, and perspectives to try on for size – all delivered in her whip-smart, delightful voice.

Her chapter on “Comparison and Competition” definitely resonated with me. Tiffany is one of the few how-to authors I’ve seen who addresses the not terribly noble feelings of envy, jealousy, and other emotional responses that we are not exactly proud of experiencing. Anne Lamott’s excellent Bird By Bird is one of the only other how-tos I’ve seen that dared to touch on this topic, but Tiffany explores it in far greater detail, with a candor I found deeply refreshing.

Another chapter that hit home with me focuses on “Why You Can’t Rush Your Process.” In it, Tiffany breaks ranks with the “write every day” mantra that so many authors parrot, going so far as to grant that sometimes, “lying fallow is part of the process,” and that “so much of our creative work is built on observing, processing, thinking, understanding…paying attention.” Tiffany concludes, “You can’t create unless you fill the well.”

Don’t quit your day job

In another departure from conventional writing advice, Tiffany validates having a day job as not just a necessary evil, because it can represent “your freedom, your ticket to pursue your art…” and concludes that having a day job “empowers you and liberates your art.”

I can testify to that. As a longtime professional musician, I’m aware of the tendency of musicians to treat their “day gigs” as something to be downplayed, or even ashamed of. This is mostly vanity – a reluctance to admit that their art is not fully paying the bills. Over the past decade I’ve also met numerous authors who downplay – or flat-out hide – the fact that they rely on income from sources other than their book sales, all in an effort to appear more “successful.”

Boldly stating a perspective I’d never considered before, Tiffany writes: “This job is not where you serve your time until your ship comes in. It is your ship.” That really struck a chord with me, as I’ve earned a solid living as a writer in the corporate world for more than 20 years, and the freedom from economic worry it has provided is indeed the ship that has allowed me to pick and choose what creative direction I pursue, both as a musician and as a writer. That freedom is something I never experienced during my many “starving artist” years.

Turning her attention to career aspirations that ARE focused on writing, Tiffany offers this nuanced insight:

“Define your success not as what will make you happy, but as what can you be happy with? It’s a subtle shift in thinking that keeps you from waiting for some holy grail before you can enjoy your life or your career.”

In addition to offering deep insights, Tiffany calls on readers to ask themselves some Big Questions (kinda like that annoying Donald Maass guy is always doing) – you know, the kind of questions that force us to actually THINK. To wit, she asks: “Based on all your values, what does success mean to you? What would feel like enough?”

Then she goes on to share her own answers, in a way that made me more honest about how I’d answer myself. (Ahem – get out of my head, Tiffany!)

An even more colorful take on what to do with that damn cat

I laughed out loud when I encountered one section in Tiffany’s excellent chapter on “Knowledge Burnout and Information Overload.” The three-word subheading was simply: “F*ck the Cat.”

Don’t worry – Tiffany’s not a hater. She quickly clarifies that she’s actually a fan of Snyder’s system, along with several other well-known story structure methodologies. But she reminds us that these are simply tools, observing that “None of these writing-craft systems, or any storytelling theory, is a magic bullet or a one-size-fits-all formula. If they were, every writer who followed them would be a major bestseller.”

After dispensing with that infernal cat, Tiffany’s next chapter hits on a point very much aligned with one of Guyot’s primary warnings, observing that “…in all my years working in the publishing business I have never seen the level of industry that’s grown up in recent years around services and products marketed to authors. Writers have become not only the product but the customer.”

While she does not delve into the quality and credentials of those offering such products and services like Guyot repeatedly does, Tiffany does encourage us to “be an informed consumer and make sound, practical investment decisions.” She then offers a useful framework for reaching those decisions.

Like a bridge over troubled waters…

Near the end of TIA is one of its most prophetic and resonant chapters: “Reclaiming the Creative Spark in Troubled Times.” In it, Tiffany points out how writing can help process pain, make sense of the senseless, give voice to the voiceless, create hope, and ultimately change the world.

To be fair, she also acknowledges that this can be very hard to do, particularly during times like these:

“But even knowing the good your art may do for yourself and for the world, how can you do it amid all that angst that you, as a creative, as an extra-sensitive, deep-thinking, hyperaware artist, may be roiling with at various times of your life?

You use it.

Though it may feel unfathomable while you’re enduring them, these powerful, uncomfortable emotions can make your writing even more relevant and impactful.”

Bottom line: With The Intuitive Author, Tiffany offers a unique combination of emotional and analytical insights – all delivered with a clear-eyed realism – about pursuing a path that is challenging, intensely personal, and often far from being fair, but that can also be immensely rewarding at multiple levels.

Five stars, hands down.

How about you?

Have you read any writing how-tos recently that stood out from the pack? That pointed you in new and unexpected directions? I’m always up for reading a NTMHT (new-to-me how-to), so please chime in! And as always, thanks for reading.

Scott Frank, arguably the most successful screenwriter in Hollywood over the last four decades, at least per the author of a profile of him that appeared in The New Yorker about a year ago, claims that no book can teach an aspiring screenwriter more than Red Harvest by Dashiell Hammett. I read it again this week and, yep, I suspect he’s right.

Bart, thank you for the recommendation. I haven’t read Hammett or Chandler in many years, but remember loving them both. I just checked out a sample of Red Harvest, and I can see what Scott Frank means: It is full of the Voice-with-a-capital-V that Guyot touts in KTD.

Thanks again for the tip – I just bought the Kindle version of Red Harvest, (or RH, as the cool kids no doubt say).

Well, DAMN, Keith–what a thing to find in my in-box this morning. I can’t tell you how much this means to me to hear that the book hit the right chord with you. Truly, this is the kind of feedback any author hopes to hear about her work. Thank you with all my heart.

And you have me intrigued to read KTD. I’m a craft-book junkie too, and while I can live without the bitterness (all FULL UP on that at the moment, thanks!), I’m definitely a fan of writers finding their authentic voice and not writing to a formula. Thanks for the recommendation too!

Happy to brighten your day, Tiffany! Your book certainly illuminated my days while I was reading it, and I hope this post captures that fact.

Will definitely be buying Tiffany’s book. Great post, Keith!

Thanks, Beth – I think you’ll dig it!

Thanks greatly, Keith, for such a thorough and thoughtful review of these two craft volumes. I (like most of us, no doubt) have shelves loaded with books on the writer’s craft, and I still find myself (perhaps too insecurely) always yearning to learn more, find more help, catch more worthy counsel — while at the same time wanting to shut out advisory voices and just plain write my own way. Your post (and the passed-along insights of KTD and TIA) helps me step back, take a deep breath, and observe my core need more clearly.

Thomas, I know what you mean, and try to stay wary of falling into the writing-by-committee approach that can happen when you try to consider TOO many sources of advice/counsel. Tiffany knows, too, devoting an entire chapter to the dangers of “Knowledge Burnout and Information Overload.”

Good luck writing whatever way YOU want to write!

Keith, now these are the kinds of reviews I really enjoy. Thank you. But that title: Kill the Dog…and I just knew there had to be a cat behind it. Why are cats always cast as the villain? But seriously, as a process junkie myself, I really enjoy reading how others write and I’ve heard good things about Tiffany’s book so that’s the one I’ll be checking out. One of my favorite books on the writing life is Bruce Holland Rogers’ WORD WORK. It’s being invited to sit and have a chat and a drink with him on the pleasures and perils of this writing life. I also loved PROCESS by Sarah Stodola.

Thanks, Vijaya – I’m not familiar with either of those, so I’ll definitely be checking them out!

Thanks for the great review – sounds like one to get and let into your process for its originality.

This stuck out for me in your post: ““Voice is the distinctive qualities of your own creative personality expressed on the page…” – and it is the scariest thing for a writer to develop and USE.

Because then the READER is reacting to your very soul, to the now-disclosed way you perceive beauty and truth – and express it to tell a story that you love.

If you don’t find the readers who love that inimitable part of you, it is very lonely out there.

Ask writers to go through their books and find and share the pieces they’re happiest and proudest to have written.

If you do, it is indescribably affirming.

Thanks, Alicia. I guess there is some risk involved in exploring your Voice, but to me it’s worth it. I long ago realized I was NOT everybody’s cup of tea, so I quit trying to be. Instead, I write in a way that reflects how my mind and heart work, and some people like it, and some can’t stand it. And I’m okay with that.

I think it’s the writers who want to please everybody – or, at least not offend anybody – who are not likely to write something emotionally resonant and powerful, since they’re too busy playing it safe.

Keith, great reviews, some of the best stuff I’ve read in a long time. Thank you. I also particularly like your comment in your answer to Alicia. “Writers who want to please everybody or not offend anybody are not likely to write something emotionally resonant and powerful, since they’re too busy playing it safe.” You’re a new voice in this world of writing for me, Keith, and I’ve worked with writers for many years with developmental editing and you’re resonating with what I know from experience, too. Thank you and glad to have met ya online!

Thanks for your reviews–in particular, your review of Kill the Dog.

For years, I’ve read interviews with agents, producers and managers in which they declare that when they sit down to read a spec script, what they’re looking for is a writer with a clear and original voice. To which I always thought. . . _Why. . . ?_ Why would that be the most important thing to you? Yes, a great voice (i.e. prose style) will make the script a far more entertaining _read,_ but it’s not going to mean that it has an engaging story or characters, snappy dialogue, a great ending, terrific visuals, a worthwhile theme or any of the other things that make for a great _movie_ . In fact, a great “voice” is the one element of a screenplay that _cannot_ make it to the screen!

This search for a “great voice” always bugged the shit out of me. Because a screenplay is not a book.

BTW, whenever I offer this argument to someone telling me that a screenplay’s “voice” is the most important thing about it, they almost invariably start to backpedal on the definition of the term voice: “Well, of course the voice encompasses the characters, the plot, the dialogue–it’s the whole thing!”

Okay. I guess. If you want to make up an entirely new definition for the word “voice.”

And yet, I believe that Paul Guyot is absolutely right. Most professional readers of scripts are wooed by an entertaining prose style. I imagine because appreciating a good inside joke or a clever turn of phrase takes far less work than visualizing and hearing the script in their mind as they read–which is what they’re supposed to be doing. But I believe that that is becoming something of a lost art. I think he’s also right in his assertion that it all started with Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid.

It’s interesting to me that Goldman, who truly was a great writer for most of his career, kind of began to lose it towards the end, when he became so enamoured of his voice as a writer that he began to neglect his plot and characters, which occasionally verged on the ridiculous (try reading “Brothers,” the sequel to his brilliant book, “Marathon Man.”)

So I haven’t read Guyot’s book yet (but I will, thanks to your review) but if he advocates developing a strong authorial voice to sell screenplays, I would agree. It really is what producers and agents are looking for. Sadly.