Self-Censorship

By Kristin Hacken South | July 25, 2024 |

I’ve been in multiple book clubs, each with its own personality and reading preferences. I love book clubs for the discussions they foster and for the enthusiastic recommendations that members of those clubs make. As a result of my book clubs, I’ve read many books I would otherwise have skipped over or never even known about.

Several of my book clubs over the years have included readers who qualify their book recommendations by listing and justifying any undesirable (by their definition) elements of the book: it has a lot of swearing, but the story is important. It includes one sex scene, but it’s not too explicit. There’s a really gruesome murder, but it’s just the first chapter. For these readers, the value of the story triumphs over qualms about specific content.

Other times, the concerns win out: I wanted to read it but my sister told me it uses the f-word a lot. I don’t read books with sex scenes. And so on.

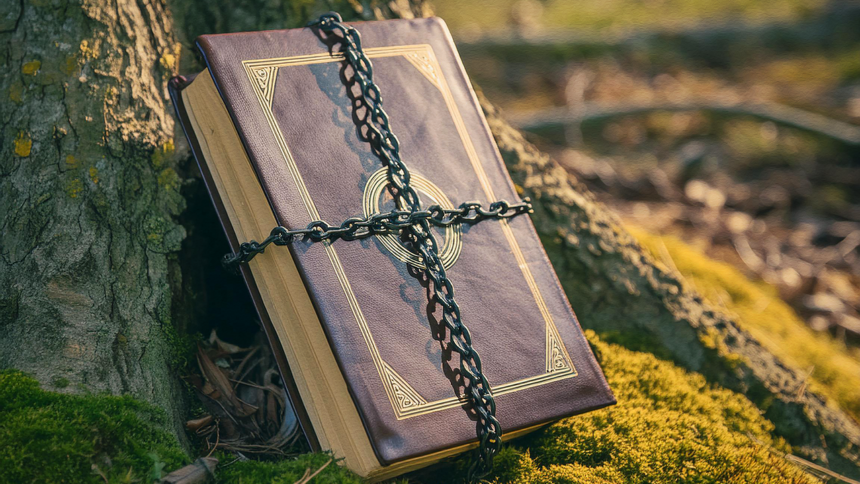

Book banning and cancel culture have become common on all political sides, with everyone citing the same putative benefit of preventing exposure to harmful content or individuals. Devoted readers and writers of all stripes, however, condemn book banning because it removes individual agency and panders to the fear that one’s own truth cannot withstand honest scrutiny.

So what should we think about self-censoring?

I believe everyone should have the right to decide for themselves what they will and won’t read, so deciding against something—while leaving it available to others—is as valid a choice as its opposite. I submit, however, that society as a whole benefits when we are willing to push our own boundaries enough to sit with the discomfort that some elements of story create.

I once taught a history class with an accompanying film lab. Every week we discussed a set of readings related to a single topic and then watched a film on Friday afternoon that explored the same issues in a way that added complexity or that drove it home in a more visceral way. My classes consisted of university students, aged 18 to 23.

One semester I taught a student—an adult, by definition—who refused on moral grounds to watch any film rated higher than PG-13. He also looked up the content of unrated films on the list, like The Third Man, and decided whether or not he considered them suitable (that one wasn’t, in his view, due to the inclusion of a two or three second scene in which a woman is dancing suggestively in a club).

Apart from making me look like an irresponsibly wanton corrupter of youth, his refusal saddened me because of how it limited his understanding. Thoughtfully told stories can drive home a lesson like nothing else can. I’ll never forget the stunned silence in the auditorium at the end of Paradise Now or the lively discussion that followed Hero. In a similar vein, I pity the readers who refuse to read Demon Copperhead because it uses authentically graphic language or who condemn the Harry Potter books for taking place in a world of witches and wizards. I can respect these readers’ adherence to their values, but I also see how my own willingness to suspend judgment has enriched my life in ways I never could have predicted.

My interest in this topic is not purely academic. I’m currently writing a book that, if it ever comes to light, might be one that book clubs decide not to read based on a truly gruesome image in an opening scene. Honestly, if someone told me about this book I’m not sure I’d want to read it. Yet here I am writing it.

You know how sometimes the book chooses the author? That’s what happened to me with this one. It’s not a book I’d write, if I felt like I had any choice in the matter. But I know better than to argue with the Muse when she comes calling. I’m grateful she chose me for this project, so I’m doing my level best with it. I hope to be able to explain to would-be readers that it’s worth dwelling on this particular horrible thing because the overall story raises awareness of an unjust aspect of contemporary society.

We can have valid reasons for choosing not to read a particular book at a particular time: past events that would be painful to revisit, especially without prior warning, for instance, or the renewal of a recent and unhealed sorrow. It might be valuable, though, to stop and parse out an inclination towards self-censoring: is it based in a genuine need for self-protection, or does it come from an unwillingness to engage with content that might force us to stretch and—gasp—grow? My own sheltered little world has expanded limitlessly as a result of things I have read. It’s almost too obvious to state, isn’t it?

I know I’m not alone:

- Stories build a bridge between us and Others we might never otherwise meet or understand.

- Stories provide vicarious enjoyment of a life we might never otherwise live.

- Stories give us a break from what can sometimes be a pretty bleak world.

- Stories quench—and also incite—curiosity.

Nothing in this post will shift the culture wars that rage all around, but I’m planting my flag: we benefit from reading books that make us uncomfortable if they also expand our world. I would not wish to deny that education and that entertainment and empathy to anyone, book club members included. Everyone benefits when more of the population has sympathy or understanding or vocabulary to communicate with others. Even if it sometimes takes an element of shock to drive the message home.

Does the end—a more educated and compassionate society—justify the means—writing and reading shocking content? What do you consider too upsetting to read? What do you refuse, on principle, to write?

[coffee]

Kristin I love your posts so much. They have a way of tilting the world back on its axis for me, even when, as today, you’re suggesting that stories knock us off in order to set us back in a new place. I agree that we must stretch to grow. As long as any manner of horrors transcend gratuitousness to make a good point, I’m in.

Thank you for your kind words, Kathryn! I’m with you up to a point–I’m a scaredy reader sometimes. More than once, though, a person has described some aspect of a book that worries me, but when I read it in context it works. Onward and upward.

Hi Kristin, what a good post today. Important subject. I like that you don’t argue with the Muse! I am not keen on the use of the F-word, but I don’t mind if a character says it from time to time in the heat of a moment (a few of my characters have just blurted it out to my surprise). When used excessively, though, the reading becomes trashy, and I have stopped reading the story and won’t read that author again because now I’ve lost the trust. I have a love of language and when it gets sleazy, I’m done. There are certain subjects I won’t read in fiction: child abuse is definitely out, and I’m very selective about any abuse of women or men.

Yes, I agree that there’s a line between gratuitous shock value and worthwhile use of strong language and themes. A friend told me once that his grandmother explained that strong feelings sometimes need strong words. That makes sense to me. Overuse cheapens their impact, though.

The Third Man! Your student missed out on perhaps the greatest of all film noir, written by Graham Greene, shot in stark light and shadows in an empty and ruined post-war Vienna, which includes one of the great villain speeches of all time, delivered with chilling, offhand conviction by Orson Wells, on a Ferris Wheel, no less, to symbolize the circular moral thinking of evil men.

If we self-censor we miss out. I do give up on books not because of their content but because sometimes they simply are artlessly written, or self-indulgent, or unrewardingly slow. Violence and sex scenes offend not when these most common human things are shown, but because when shown they are flat, adding no meaning to the acts.

Years ago, I decided not to avoid books that I thought that I wouldn’t “like”, and I’m so glad that I did. I am rich in reading as a result. Good post.

Right?? The Third Man is dead brilliant. And you have honed in on precisely the scene and the themes that we discussed afterward. The fog of war smudges out the goodness in impressionable people, which is something different that those who choose to stand in the shadows.

The books you do not finish sound more like quality control than censorship. :)

Hello Kristen, and thank you for your post.

I’m intrigued by how many encounters you’ve had with people who suffer from prurient obsessions. People already preoccupied by libidinous thoughts are often the ones most fearful of being exposed to depictions or descriptions of the erotic. The others you speak of fear exposure to profanity, or depictions of violence. At the heart of such self-censorship is a central belief among many who are conservative and religious. This is a conviction that sin or evil is communicable, like a virus. Refusing to see or read certain material is the equivalent of wearing a mask. Some of these people see themselves as morally obligated to protect the whole community from infection (book banning).

The first kind of self-censorship I make use of is to avoid obvious efforts to exploit sex, violence or profanity. Instead of these elements being integral to character and story, I sense they are being laid on for shock value. It’s what David Corbett might describe as the reader becoming aware of the machinery of manipulation. That’s offensive and insulting to me.

My second, even more important censoring mechanism is a strong wish to not be bored. Never mind the subject matter or characters. If it strikes me as unworthy of my attention, end of story.

Yours however is a very worthy topic, and thank you again for taking it up.

You called it, Barry: fear of communicable sin is the focus of a lot of religious prohibition. And yes, I have spent a lot of time amongst people who think that way. It has been a conscious choice to expand my world beyond that way of thinking, and I feel richer in understanding for having done so.

You make a good point that shock value can be an attempt at cheap, manipulative emotional appeal. As I think about it, that’s another reason I’ve been leery to write anything that could be seen as over the top. It’s such a balance, isn’t it?

I feel like this is the key caveat: “we benefit from reading books that make us uncomfortable if they also expand our world.”

I won’t start a book if I know it includes scenes of animal cruelty. I can appreciate that, as a result, I may be guilty of the charge of narrowmindedness, but I have never encountered a scene with animal cruelty which seemed absolutely essential to the broader story or expanded my world. And, given that, I can imagine people feeling similarly about other scenarios, e.g., the gratuitous abuse of women or children.

I don’t disagree with your basic premise. However, I am hesitant to believe that whatever line I draw should be adopted by others. To me, the high moral horse your student sat upon seems foolish. But, I suspect, he might feel similarly about the line I’ve drawn on animal cruelty because, after all, God has given Man dominion over all animals. And I’m not certain either of us pitying the other (which feels sort of condescending) accomplishes much. Wouldn’t it be better to simply respect the difference and insist that people don’t try to impose their values, whatever they are, on others?

Good points, Bart. The freedom of choosing to read a book with certain elements is also the freedom to refuse to read it for certain elements. There is nothing wrong with that.

Hi, Bart! I’m glad you focused in on not being condescending toward others. I hesitated over my use of the word “pity” for the very reason you objected to it: it can seem judgmental. In the end, I decided that I really do pity people who refuse to engage with meaningful or (in the case of Harry Potter) joyfully imaginative content on what seem like superficial reasons. I don’t judge them, but I feel sorry for the high quality experiences they’re missing out on. That said, you’re right that respect for others’ values is essential to a well functioning society. Plus, life is long and people can change. I know I have!

Hi, Kristin! I meant to reply to your response but… life interceded. I understand your perspective but also, personally, feel uneasy about it as a writer and someone who feels our world would probably be a better place if each of us valued empathy a bit more.

Note the origin of your pity. It’s a person’s unwillingness to “engage with meaningful or… joyfully imaginative content” for “what seem [to you] like superficial reasons.”

Empathy requires us to set aside our values, preferences, etc. in an effort to better understand someone else. Said differently, in terms of empathy, your personal perspective of the person’s reasons for not engaging with the content, whether you consider them superficial or not, is perfectly irrelevant. What matters is that they’re anything but superficial to the person that holds them.

You’ve made an odd sort of argument. You’re being critical of someone for being close-minded while guilty of the same. You pity him, and, I suspect, he pities you in equal (or greater) measure. But that doesn’t bother you because you’re confident your values are valid while his are, at best, misguided and superficial. But that doesn’t bother him either because he knows the same about you and your values. Where do we go from there?

In terms of writing, such a lack of empathy seems like a significant liability. Is it possible to pity a character for their ignorance and make him or her anything other than a cardboard cutout? I suppose a writer could simply avoid characters with values that differ from their own, but it seems like you and the person you mentioned would be an ideal protagonist-antagonist combination. Yet, on paper, just as in life, your antagonist would come across as cartoonish unless you’re capable of seeing the world through his eyes.

Hi back, Bart.

Thank you for taking the time to write this thoughtful reply. As I mentioned in my earlier comment, I hesitated about including the word “pity” and in the end I decided that it did accurately represent an aspect of my feelings on this complicated topic. On reflection, I wonder if I thought I was conveying something different than what came across. If you’ll allow me to reword, then we can see if your objections stand. If so, I am happy to continue the discussion!

As I read your reply, three ideas stand out. Let me know if I’ve gotten this wrong. I think you are uneasy with 1) my use of the word “pity” and the judgment that it implies, 2) my definition of some reasons for self-censorship as superficial; and 3) the lack of empathy that these ideas imply.

Let’s take them one by one.

1) When I wrote “I pity the readers who refuse to read [a certain kind of book],” I meant “I am sad for what they are missing.” I was not implying superiority or judgment of those readers and it was not meant critically. I do not mean to call them close-minded and I’m sorry that that implication arose for you. I am saying that I personally feel sad for them.

I continued in the next sentence to say “I can respect these readers’ adherence to their values.” Perhaps I should have expanded on that further: I know and love many such readers and I do understand where they’re coming from. I’ve been one of them, as I hinted with the rest of that thought: “I also see how my own willingness to suspend judgment has enriched my life.”

I wonder if the contrasts in our understanding have something to do with definitions of the word “pity.” The etymology-by-way-of-Google rabbit hole says that there are two ways of seeing that word, one with a negative valence (“I feel superior to you”) and one without (“I feel compassion toward you”). I really did mean the second. And yes, I understand that they may feel sad for me in return. I can’t change that and wouldn’t try. It’s all part of accepting that people have different perspectives.

2) The examples I gave in the first paragraph, all of which I’ve heard frequently in book clubs, were based on objections to a single element of the story that might been seen to disqualify it even though the readers valued their overall storyline or message. This is what I mean by “superficial.” I see it as a distinction between something that is on the surface (an aspect of how the story is conveyed) versus something that is so deeply embedded as to be integral to its substance: perhaps it’s the difference between a rating and a trigger warning. One tells you what it contains on a generic level (language, sexual content, violence) while the other delves into situational specifics (perhaps like the animal cruelty and abuse of women and children that you named). It’s exterior paint versus load-bearing walls.

In hindsight I see that “superficial” is another word that can have a negative valence while I intended to use it as a neutral descriptor. That was my error. Specificity in words matters and you are right to call me out on it.

3. I hope that at this point you do sense that I am trying to bring empathy to my thinking about this topic as well as to my writing. I believe that analyzing our discomfort with some kinds of books but not others encourages rather than limits empathy. I’m curious what our own and others’ backgrounds and tolerances mean in terms of how and when and why we’re willing to engage or not.

Society is full of people who exude blanket disdain for those with whom they disagree. When I hear people say, “I just don’t understand how you can [do something or feel a certain way],” what I actually hear is “I choose not to engage in a meaningful way with you in order to understand you.” The job of a writer/teacher/citizen/good neighbor is to say, instead, “I don’t understand. Please tell me more.”

Bart, I do not know you in person but I thank you for challenging me on this. Please believe that I did not intend to imply any superiority or criticism. I am curious and I want to understand better why people, myself included, behave as they do. As I wrote about self-censoring, I fear that it is sometimes rooted in “the fear that one’s own truth cannot withstand honest scrutiny.” I am grateful for the honest scrutiny you have brought to the implications of this post.

Wow. Not wanting to watch The Third Man? What a loss for that young man. I can only imagine the other students shaking their heads at this decision after seeing what a masterpiece of film that it is.

We all have likes and dislikes, and I have read books for my own book club that I would have never read on my own, which is a good thing. Like some others here I don’t like gratuitous violence. Watching or reading about people suffer violence like that is not entertaining to me. It is the same reason I don’t consume all of those true crime podcasts and tv shows. I don’t see how these enrich or expand my experience as a person in this world. Of course I would never try to stop others from enjoying these. Good post.

I have the same concern with true crime! I can’t explain why I devour fictional crime but hate true crime, except that it seems voyeuristic. It makes me uncomfortable to know that it really happened, even though some fictional crime scenes can describe even worse situations! I don’t judge others who enjoy them but like you, I can’t enjoy them myself. Thanks for chiming in.

Kristin, great essay. And I’m glad you’re following your muse, come what may. Flannery O’Connor used shock to wake people up to the action of grace. I typically do not read horror but her stories are so arresting. They made me see. I don’t like violence just for the sake of it. It must serve the story. And the reader has to be ready for the story too. Les Miserables by Victor Hugo comes to mind. Twice, when I picked it up, I couldn’t get past 50 pages, but the third time, living in Belgium, I devoured it. It was simply the right time.

I’m also working on a story that makes me feel uncomfortable–in the early stages, I had to write and not think about my audience. Now that I’m revising, I’m very much aware that some people will choose not to read it. That’s okay. I’m not writing for everybody.

Vijaya, you’ve reminded me that I have tried to start East of Eden more than once and had to put it down. As a mother of boys, I found it too threatening. Now that they’re grown, maybe I can give it another try. :)

You’re right that no book will appeal to every reader. The reasons people don’t read are as varied as the reasons they do. I’ve come to the same conclusion as you: I write what I write because it needs writing, and I hope its readers will find it.

Reading your post and all the comments, this discussion falls to personal opinion. Basically, I believe that readers have a right to know a bit about content (read a review, the book cover etc) …but that readers should also believe in freedom of speech, the right of writers to create the characters and situations that inspire them. I am currently querying my novel, and I know that some agents have strict rules as to what they will and won’t promote. That is their choice. But does a few paragraphs about a novel truly reveal the message and the worthwhile involvement that a reader will encounter? I think not. Final point…one can always close the book…or hang in there to see how the author has fulfilled the book’s promise.

I absolutely agree, Beth, that our decisions on this point must be highly subjective. I love having the freedom both to read and to choose not to finish (or sometimes even start) certain books. As to your point about content warnings, I’ll respond more below.

First, thank you for mentioning “Paradise Now,” a masterpiece of film and an education in compassion. Second, this is a wonderful discussion! Self-censorship is limiting when there are a number of shallow elements one avoids (sex, swearing), but I can understand not reading a book because of something deeper that feels more than uncomfortable, but perhaps actually causes anxiety — such as animal abuse, child death, sexual assault, etc. Still, i do think it’s good to at least try and approach these books and deepen our human capacity to feel.

I agree, Stella, that discomfort can occur on different levels. As I tried to say above, yes, it’s the shallowness of indiscriminately avoiding surface-level content that I feel is unduly limiting. It has nothing to do with the actual value of a story.

I didn’t grow up with the idea of trigger warnings, but in at least one memorable case, I desperately wish I’d had one. Coming across deeply disturbing content when one is already traumatized in that direction can cause harm. Sometimes it really is too soon. On the other hand, engaging with hard things can show the way to triumph over them. It depends in part, I think, on how the author portrays it.

interesting topic. Odd how even on this blog during a flogging of a quill ( a regular occurrence) how many of us confess to self censor by genre.

Haha, you are so right about the monthly floggings! I’m not sure if that’s censorship per se or just people having personal favorites.

I do have one omnivorous friend who seeks out the best books in disparate genres just to make sure he’s tried them all. After he told me about it, I went and read my first western, a classic by Zane Grey. It was an education! I probably won’t read a lot more in that genre but I’m glad to have experienced it.

Back to the floggings, though: yours is a good reminder. No matter how often we are told to look only at the quality of the writing, it’s hard to get past personal preferences.

I keep this essay and read it over and over because it articulates so much better than I can my rationale on the inclusion of dark/uncomfortable scenes. A favorite quote of mine from Akira Kurosawa: The role of the artist is to not look away.

Thank you for your comment, Kelly! I’m so glad that I was able to write something that resonated for you. And that quote seems particularly timely. Thank you for sharing it.