Lessons from the Evil Spawn

By Dave King | August 15, 2023 |

Ruth and I are currently binging Grey’s Anatomy – centered around a group of surgeons at a fictional Seattle hospital — and enjoying it for all sorts of reasons. (Bailey is brilliant.) Remarkably, the show is still fresh and original after nineteen seasons. Most shows, even the best, rarely last more than five or six without falling apart – the phrase “Jumping the Shark” comes from the episode in the fifth season of Happy Days when the show crossed a line there was no coming back from.

Ruth and I are currently binging Grey’s Anatomy – centered around a group of surgeons at a fictional Seattle hospital — and enjoying it for all sorts of reasons. (Bailey is brilliant.) Remarkably, the show is still fresh and original after nineteen seasons. Most shows, even the best, rarely last more than five or six without falling apart – the phrase “Jumping the Shark” comes from the episode in the fifth season of Happy Days when the show crossed a line there was no coming back from.

Why should writers be interested in a television show? Writing and screenwriting have different tropes, techniques, and expectations. And Gray’s Anatomy has regularly replaced cast members, a technique that also helped other longrunning shows, (MASH or the Law and Order franchise) stay fresh. Writers can’t exactly introduce new characters mid-novel.

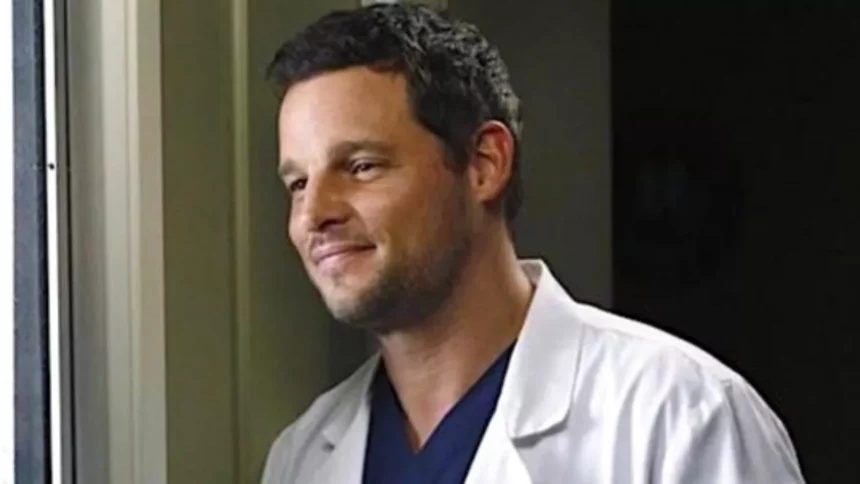

Still, many Gray’s Anatomy characters last for a decade or more without becoming repetitive or ridiculous, and three of them – Meredith, Bailey, and Weber – have been there since the beginning. These characters stay interesting because they are developed to a depth that writers can only envy – and learn from. I’d like to focus on one in particular, Dr. Alex Kaerv, played for sixteen seasons by Justin Chambers. I think it goes without saying, but spoilers abound.

Writers know their heroes have to be flawed and their villains have to be sympathetic. They also know that characters need to grow, to overcome difficulties in the course of the story. The go-to trope for all of this is a troubled childhood — sensibly enough, since this is where a lot of character problems have their roots in real life.

Alex grew up with a drug-addicted father who abandoned the family when his mother developed schizophrenia. While Alex was still a child, he had to not only care for his younger brother and sister, he had to make sure his mother took her meds — too many responsibilities way too young. He kept his situation secret out of shame, which prevented him from forming friendships outside the family. He eventually wound up in foster homes – and getting thrown out of foster homes – before finally going to med school on a wrestling scholarship. This all left him angry and emotionally stunted, with a willingness to lash out and step over others to get what he wanted. So much so that in season one, Cristina Yang dubs him “Evil Spawn.”

Alex eventually overcomes a lot of this damage in ways writers might be familiar with. When his brother comes to him for medical help, he reveals a lot of Alex’s history, something Alex kept hidden out of habit. Yet his fellow residents don’t hold him in contempt (or in Cristina’s case, more contempt – she has her own issues). He later brings a patient with psychological problems home with him, to take care of her, much as he cared for his mother. When he’s forced to commit her, he learns that his habit of caring for crazy people has its limits. And when his father shows up at the hospital, Alex is still angry, refusing to see him and later punching him out. When his father returns to the hospital again some time later, Alex manages to reconcile with him before he dies.

Too many writers stop there, treating a character’s childhood damage as a problem to be solved. And once it’s solved, it’s gone. Alex’s story shows that life is a lot more complicated than that.

For one thing, his problems don’t go away after they’re “solved.” Long after he’s developed some compassion, genuine friendships, and a sense of self worth, he believes an intern, DeLuca, took advantage of the new love of his life, Jo Wilson, while she was drunk. He beats DeLuca to the point of nearly blinding him. Afterwards, he’s shocked that he has this much violence still in him, but it’s there. Then later, when he discovers that Jo’s first husband was also abusive, he has to fight to not hunt him down and hurt him. His broken childhood heals, but the scars remain.

More important, Alex’s best characteristics as an adult are rooted in his childhood trauma. He doesn’t overcome his damage and put it behind him. He harnesses it. By being forced to care for his mother, he developed a habit of sacrificing himself to care for his patients, to the point where he nearly misses his board exams to take care of a premature baby whose organs were failing. (Note, there were other doctors on the scene. Alex did not need to be there to save the child’s life.)

His often unsympathetic bluntness (“Look, your kid’s going to die anyway, so you may as well . . .”) convinces several nervous parents to agree to give their children needed surgery. This bluntness also endears him to a lot of his child patients – kids can detect false cheer and respect honesty. Being robbed of his own childhood, and the emotional stunting that results, lets him connect with the children he treats, making him a very effective pediatric surgeon. At one point, he convinces a five or six year old that the tumor he’s removing is a little man living inside of the boy that Alex will dismember in ways that he describes with relish and in gruesome detail. It’s exactly what the kid needs to hear, and Alex saw that.

If you can get past seeing your character’s flaws in black and white terms – seeing that flaws can also be strengths, and vice versa – you have room to take your character to more interesting places. You also have a chance to develop more interesting conflicts with other characters. The best clashes aren’t the ones where one side is right and the other is wrong. It’s where readers can see both sides and aren’t sure which side they’re on.

Alex is attracted to Izzy Stevens, a fellow intern, early on. But several seasons pass before he grows up enough to have a relationship with her. In the meantime, Izzy falls in love with a patient who later dies. (Izzy has issues, too.) When she starts seeing the ghost of the dead patient, Alex dismisses the visions as unimportant because his experience with his mother made craziness feel normal. When Izzy finds the hallucinations are the result of a brain tumor, Alex is devastated for not noticing it earlier. She eventually has the tumor removed and undergoes grueling chemotherapy, with Alex by her side, eventually marrying her. But when she resumes work, he pushes a little too hard to care for her – yanking her out of an OR to make her take her medications, for instance.

There’s no clear right or wrong here. Izzy neglects herself because she wants to put the cancer behind her and focus on her career. Alex pushes hard from both guilt that he missed the cancer and terror that Izzy’s ignoring her problem, which brings up echoes of his mother. It’s hard to see how they can make it together because it’s hard to see how either one of them could do otherwise and still be themselves. And . . . they don’t. To protect her, Alex tells his attendings that he’s afraid Izzy is pushing herself too hard, which leads them to suspend her from the residency program. Izzy blames him for torpedoing her career and disappears, leaving him frantic for her health. When she returns, he can’t forgive her for abandoning him, which brings up echoes of his father, and they eventually part ways. (They also get together in the end, but that’s another story.)

I do believe in right and wrong and am cool with characters who have moral cores. I also believe humanity is often more complicated than that. If you ignore moral ambiguity – if one side is always clearly right and the other side equally wrong – your stories will tend to be more predictable and less interesting. There’s some dramatic tension in whether the good guys or the bad guys win. There is often more in seeing both sides as good guys and hoping they find a way to both win. Watching a virtuous character triumph is far less interesting that watching a flawed character find a way to use their flaws to get where they need to go.

I picked Gray’s Anatomy because Shonda Rhimes is brilliant at characterization. But there are examples of this kind of flawed character in literature — Graham Greene’s Whiskey Priest comes to mind.

So who are your favorite examples of flawed character whose flaws turn out to be virtues?

[coffee]

Gray’s Anatomy. The Evil Spawn was my favorite character, next to Bailey (she is just so darn human.) Alex, too. I remembering thinking “oh, no, what’s he doing??” so many times and almost hating him, then falling in love with his brokenness all over again. I’m currently reading a Fantasy trilogy with a main character who is throughly flawed but has a Code, which I love so much, especially in this world of Code-less bad actors. To do the wrong thing for the right reason takes nerve and resolve and maybe a bit of crazy. As a child, I venerated Robin Hood, and though I’ve since learned more about the man, the legend will always live for me as the social justice guy who turned a resentment it into something heroic.

His betraying Meredith and the clinical trial was a low moment, but I think they redeemed him skillfully. And you’re right about the moral ambiguity of bad actors who have a code. I’m reminded of Raymond Chandler’s observation on the kind of noir heroes he wrote about. “Down these mean streets a man must go who is not himself mean, who is neither tarnished nor afraid.”

I swear Gray’s Anatomy is the only thing that got me through the pandemic. What a great examination of the complexity that makes this show so compelling. Thought-provoking column. Thanks!

Hello Dave. I think I see why you admire Grey’s Anatomy. It is not simple-minded. It doesn’t insult the viewer’s intelligence by creating a character’s standard Freudian lousy-childhood background and simply “fixing ” the character. But isn’t that aspect driven by the ongoing nature of the TV series? You can’t fix things if you need to keep the ball rolling for years. In contrast to cop and comedy shows, I think a drama in which a character persists through sixteen seasons has to be taking lessons from soap operas. Even so, I understand the point you’re trying to make for writers: don’t overlook the possibility of flaws and damage being integral to a character’s strengths and appeal. At the same time, I think relating a TV series of such duration (not a stand-alone drama or film) means you are making an apple-and-oranges comparison. Yes, Graham Greene’s alcoholic priest may be more capable of understanding or being useful to other characters, or just more sympathetic. As you rightly say, heroes must be flawed, villains attractive in some way. But a drunk in a Roman collar for sixteen seasons? That would have to be a sitcom.

Thanks for one more thought-provoking post.

Hey, Barry,

I think you may be connecting depth of characterization and longevity of a series a bit more tightly than I have. The longevity of Gray’s Anatomy depends on the depth of its characterization, but depth of characterization is useful beyond longevity. As I say, if you can get past seeing a character’s attributes in black and white terms, it expands opportunities for dramatic conflict and deepens character, even in a short work.

This was a good reminder about people not being just good or just bad.

Just finished reading an ARC of The River We Remember by William Kent Krueger and several characters are seriously flawed, but also have redeeming qualities and moments where their flaws impact other characters. One of those moments involves a character, Felix, a WWI veteran who has a Purple Heart. Felix drinks too much and is known as the town drunk. When Scott, a 14-year-old character saves a girl from drowning, Felix gives the medal to the boy. Tells him something like, “this is a reminder of how good you are. How strong you are. No matter what ever else happens in your life.”

Hi Dave, having working as a maternity RN in a Chicago hospital, I LOVE watching medical shows. And though I agree Shonda Rhimes certainly knows how to craft a story, Grey’s Anatomy (very clever, named after a character but echoing a famous medical textbook) was never my favorite. In fact, after a while I stopped watching it. Too many characters? Too much about those characters and not enough about medicine, patients? But GREY’S keeps coming back…we lost New Amsterdam this past season, and The Resident is struggling. Bottom line, there will always be medical shows…so many of us love watching them… Grey’s has stood the test of time, probably because of its characters…not its handling of medicine.

I have heard from other sources that Gray’s handling of medicine is not the best. I have noticed that the patients are often an excuse for characters to work through their own issues, though I’m willing to forgive that.

Curiously, according to medical people (and you may confirm this) one of the most accurate medical shows was Scrubs.

Wow, I love that, Dave, and cannot confirm. I watched Scrubs maybe once. Did the characters not appeal; was the talk too brisk or wacky and weird? I so appreciate your response; something to research…. I might have missed out on a lot. Beth

It was pretty wacky, but still fun. We watched most of its run.

I think I may have phrased my question at the end badly, and bringing up the Whiskey Priest complicated matters further. What I’m looking for is not just flawed characters with redeeming characteristics. I’m looking for flawed characters whose flaws ARE their redeeming characteristics.

One example I can think of offhand is Larry Niven’s The Ringworld Engineers. This is the sequel to Ringworld, where Louis Wu is recruited to visit a remarkable (and remarkably described) structure in space. The book opens with Louis Wu the futuristic equivalent of a drug addict — a wirehead, with a probe directly into the pleasure center of the brain fed by an outside stimulator. Louis is kidnapped and brought back to Ringworld by an alien who controls him by controlling access to the stimulator. To escape the control, Louis kicks the wirehead habit.

Well and good. But later, he and other expedition members are exposed to a plant whose smell (for reasons far too complicated to explain) is intensely addictive to humans. To the point that it dominates their brains to the exclusion of everything else. Though it costs him dearly, Louis manages to keep in control and help his fellow members escape. As he later says, no one but a reformed wirehead could have done it.

Lord Peter Wimsey’s horrible experiences in “The Great War” left him with what we’d call PTSD. His humor–irrepressible, irresponsible, sometimes inane–and many aspects of his lifestyle are probably defense mechanisms. While he’s irresistibly entertaining, the pain comes through.

Yes, excellent example. And though I haven’t read the Sayers books in a while, I seem to remember that Lord Peter became less inane as time went on. By the time he and Harriet married, he was pretty level headed.

I often use Rudolph the Red Nosed Reindeer in my workshops with children to show how the very thing that feels like a curse can actually be the saving grace. And of course, we all sing it. I’ve not watched any TV for decades but I know I’d enjoy Grey’s Anatomy because I enjoy both medically-minded and character-driven stories. I remember Doctor in the House during my teens–a British show about medical students and it was hilarious. The characterizations were shallow but I didn’t mind. Thanks for a great post–I might even figure out how to watch TV again.

An excellent, age appropriate example.

And we’ve enjoyed Brit medical dramas, as well — The Royal, Peak Practice, Dr. Finlay. They do have a slightly lighter touch and most have had a shorter run than Gray’s anatomy. But they are still fun.