When Your Publishing Contract Flies a Red Flag: Clauses to Watch Out For

By Victoria Strauss | February 24, 2023 |

After the excitement of a “yes” from a publisher comes the job of assessing your publishing contract.

Facing down ten pages of dense legalese can be a daunting task, especially for new and inexperienced writers, who may not have the resources to hire a literary lawyer, or have access to a knowledgeable person who can help de-mystify the offer terms.

And it is really, really important to assess and understand those terms, because publishing contracts are written to the advantage of publishers. While a good contract should strike a reasonable balance between the publisher’s interests and the writer’s benefit, a bad contract…not so much.

In this article, I’m going to focus on contract language that gives too much benefit to the publisher, and too little to the author. Consider these contract clauses to be red flags wherever you encounter them. (All of the images below are taken from contracts that have been shared with me by authors.)

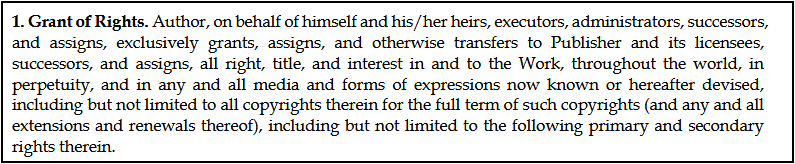

Copyright Transfer

Unless you are doing work-for-hire, such as writing for a media tie-in franchise, a publisher should not take ownership of your copyright. For most publishers, copyright ownership doesn’t provide any meaningful advantage over a conventional grant of rights, and there’s no reason to require it. Even where the transfer is temporary, with rights reverting back to you at some point, it doesn’t change the fact that for as long as the contract is in force, your copyright does not belong to you.

Copyright transfers usually appear in the Grant of Rights clause. Look for phrases like “all right, title and interest in and to the Work” and “including but not limited to all copyrights therein.”

Watch out also for contracts where a copyright transfer in the Grant of Rights clause is contradicted by language later on–such as requiring the publisher to print a copyright notice in the name of the author (which shouldn’t be possible if the author no longer owns the copyright). For one thing, you don’t want your contract to be internally contradictory, which could pose legal issues down the road. For another, such contradictions suggest that the publisher doesn’t understand its own contract language, which is never a good thing.

There’s more on the not-uncommon problem of internal contradictions here.

Life of Copyright Grant Without Adequate Reversion Language

Big publishers routinely require you to grant rights for the full term of copyright (in the US, Canada, and most of Europe, your lifetime plus 70 years). Although they’re more likely to offer time-limited contracts, many smaller presses do as well.

Contrary to much popular belief, this is not necessarily a red flag…as long it’s balanced by clear, detailed language that ensures you can request contract termination and rights reversion once sales drop below specific benchmarks: for example, fewer than 100 copies sold during the previous 12 months, or less than $250 in royalties paid in each of two prior royalty periods. Publishers like to sit on rights, because they can make money from even low-selling books if they have a big enough catalog. Authors, on the other hand, don’t benefit from a book that’s selling only a handful of copies and getting no promotional support. At that point, it’s better to be able to revert your rights and do something else with them.

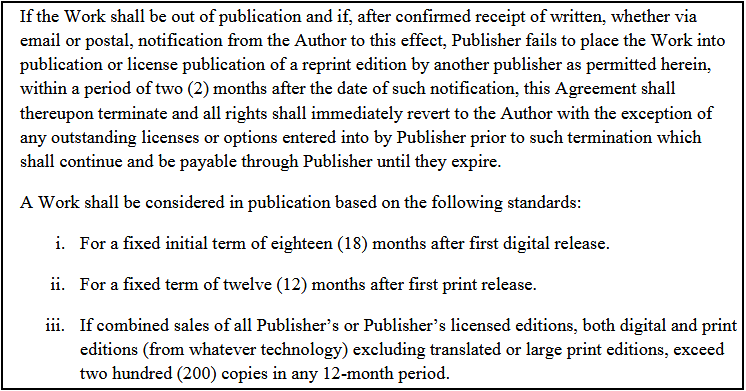

If you’re offered a contract with a life of copyright grant term, the first thing you should look at is the termination and reversion clause. A good clause will be specific about when and how the book will go “out of print” or “out of publication”, and what the author can do to terminate the contract once that happens.

In the clause below, the definition of “in publication” is tied to objective standards, including minimum sales numbers, and there’s a clear procedure for both the author and publisher to follow to request and grant rights reversion once falling sales take the book “out of publication”.

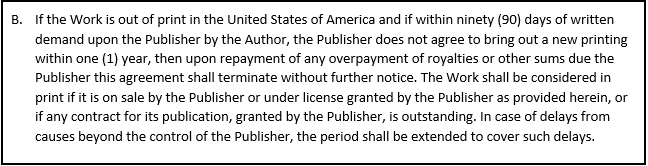

By contrast, here’s an example of a poor reversion clause.

Defining “in print” as “on sale by the Publisher” (similar problematic terminology: “available for sale in any edition” or “available for sale through the ordinary channels of the book trade”) means that an ebook edition available only on the publisher’s website would qualify as “in print”, even if it was barely selling or not selling at all. Since it costs little or nothing to keep a book “available” this way, the publisher has no incentive ever to take the book “out of print”, and the author has no leverage to compel the return of rights.

There’s a more detailed discussion of the importance of reversion clauses here.

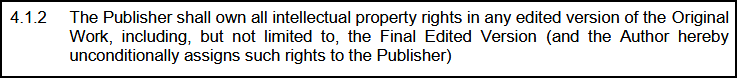

Claiming Copyright on Edits

Can a publisher claim that it owns the copyright on the editing it provides?

As far as I know there’s no legal precedent for such a claim, and the very limited legal discussion I’ve seen leans toward the view that editing process doesn’t give the publisher—or the editor—any copyright ownership. After all, other than copy editing, most editing is a collaboration between author and editor, with the bulk of the work done by the author.

Claiming copyright on edits is not standard publishing practice. Nevertheless, some publishers do attempt it, either with an outright claim of copyright on the final version of the work…

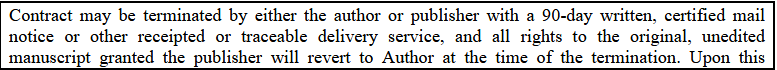

…or simply a claim on the edits themselves (telltale language: “original, unedited manuscript”):

It’s unlikely that either of these clauses would hold up in court—especially the first one: among other things, the presence of a copyright notice in the author’s name inside the book would certainly seem to indicate the publisher’s acknowledgment of the author’s ownership of the finished product. What good does it do the publisher to hoard edits on a book it doesn’t own, anyway? What difference does it make if an author re-publishes their fully-edited book once rights have reverted? Claiming copyright on edits is simply pointless and greedy.

Editing copyright claims can occur throughout a contract: I’ve seen them in the grant of rights section, the termination section, and the editing section. So keep a sharp eye out.

Net Profit Royalties

While larger publishing houses tend to pay royalties as a percentage of a book’s list price, smaller publishers often pay based on net revenue or net sales income: list price less wholesalers’ and retailers’ discounts and channel fees.

Less common are royalty payments on net profit: list price less discounts less some or all of the expense of publishing.

Net profit royalty clauses are always a contract red flag. Even at higher royalty percentages, expense deductions can drastically reduce the amount on which your royalties are based: that 50% royalty may seem generous, but depending on what’s taken out before it’s calculated, what you actually receive may turn out to be much less than you expected. Additionally, net profit royalties are a temptation for publishers manipulate expenses to make author payments as small as possible.

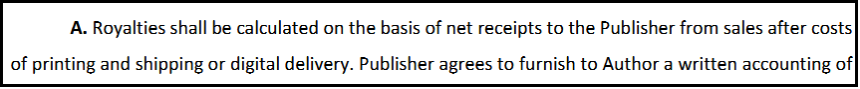

Here’s a fairly straightforward example of a net profit royalty: sales receipts less printing and shipping.

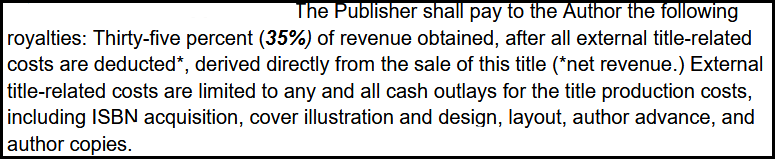

Here’s a clause that deducts much more, including ISBN, cover art, layout and formatting, author copies, and possibly other costs. Not only does this have the potential to reduce your royalty to a pittance, you won’t have any idea of why you were paid what you were paid unless the publisher provides an itemized accounting.

Some publishers with net profit royalties confuse the issue by claiming to pay on “gross income” or “net sales price” or similar terms that don’t include the word “profit”. This is why you always want to see a precise definition of whatever terminology the publisher uses to describe its royalty payments, so you can be sure exactly how your royalties will be calculated. The absence of such a definition is another red flag.

Some publishers with net profit royalties confuse the issue by claiming to pay on “gross income” or “net sales price” or similar terms that don’t include the word “profit”. This is why you always want to see a precise definition of whatever terminology the publisher uses to describe its royalty payments, so you can be sure exactly how your royalties will be calculated. The absence of such a definition is another red flag.

Early Termination Fees

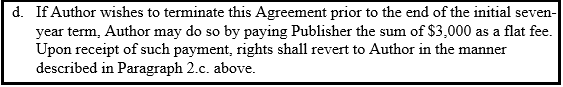

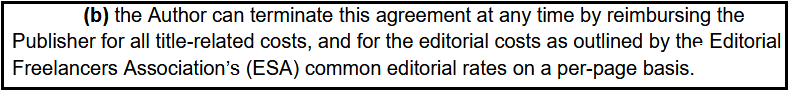

Some publishers make it possible for authors to exit their contracts early by paying fees. Sometimes this is a flat amount that may or may not relate to the publisher’s actual investment in the book:

Or it may be a combination of publication costs, such as editing and cover art, that the author has to trust the publisher to determine. (And yes, this is from the same contract as the second net profit clause above. Where one bad clause is, others often follow.)

Publishers that include early termination fees in their contracts often argue that they’re just making sure they recoup their investments on books that don’t finish out their contract terms. Or they may say that they’re disincentivizing author departures by making them expensive (though in that case, why allow early termination at all?).

But charging a flat fee that may or may not reflect actual production expense, or forcing the author to pay back all costs of publication, ignores the fact that the book has probably been on sale for months or years, and has already made money for the publisher. What early termination fees often amount to is a way for publishers to monetize author departures.

As you can imagine, this opens up the possibility of abuse–which is why early termination fees are a red flag, even if you have no intention of ever leaving early. Writer Beware has received reports of authors threatened with fees in retaliation for complaints, or told they’d have to pay even though early termination was the publisher’s decision. One publisher we know of had an annual “escape month”, where authors (usually those with low sales) were encouraged to end their contracts early by paying thousands of dollars in publishing costs they had no way of verifying. Kicking authors out the door, in other words, was more lucrative than keeping them.

What Should You Do if You Encounter Red Flag Contract Clauses?

The contract clauses I’ve highlighted above can be framed in many different ways and appear at many different points in a publishing contract. You may not encounter the exact examples I’ve provided (I’d love to offer more but then this post would be even longer than it already is). Hopefully, though, they’re enough to give you an idea of what to watch for.

It’s always worthwhile to try and negotiate better terms. Publishers vary widely in what parts of their contracts they will agree to negotiate, but they should be willing to consider at least the possibility of making changes. A flat refusal to negotiate is another red flag—as is any attempt to convince you that the contract language doesn’t mean what you think it means, or that “we never do that” (then why is the language included?). Publishers can and do try to gaslight authors who ask questions. (For more on that tricky issue, see my blog post: Evaluating Publishing Contracts: Six Ways You May Be Sabotaging Yourself.)

Even if the publisher is flexible, though, you need to consider what it says about the publisher, its attitude toward its authors, or possibly its competence, that it would offer author-unfriendly contract language to begin with. That may ultimately make it wiser to choose the more drastic alternative: walking away.

Have you ever been offered a contract with one or more red flag clauses? Have you ever been burned by net profit royalties or early termination fees or some other author-unfriendly contract language?

Victoria, you are a treasure. All the work you do to protect authors is heroic. I had an experience when my publisher passed away. He was a small indie house, published three of my novels in print, and left no provisions for his authors or their books, copyright, files, etc. Unfortunately, his wife couldn’t deal with the business problems that resulted and offered no help. I had to consult with a lawyer, write letters, and follow-up communications for months to get the copyright reversed. I did finally get back my copyrights and have a letter from the indie house lawyer that “all copyrights are returned to authors.” My problem now is Amazon. When I want to republish my print books (or go with another publishing house to publish them), I’m hearing that Amazon refuses to publish titles that were previously owned by a publishing house. Even when the author supplies them with the official legal letter confirming copyright is reversed. There are plenty of stories out there where titles have been deleted by Amazon. If you have any suggestions on how an author should proceed to republish (Amazon department? Names?), that would be helpful. Going through the normal channels of Amazon customer service is often a dead end. Your thoughts?

My publisher is terminally ill and closing his publishing business March 1. He has rights to eight of my books, although I paid a designer for my covers he used. But will I need to change the book titles and images? Of course I will have to buy new ISBN numbers, so that might mean I have to tweak titles.

Hi, Carole,

I’m sorry to hear about your publisher–that’s such a bummer.

As long as you get a document from your publisher officially reverting rights to you (if you own the cover images, the document should mention that those rights return to you as well), you shouldn’t need to change the titles or the images unless you want to. For example, you might decide to refresh the covers with new title fonts, or new back cover copy. You can use the same titles with the new ISBNs (ISBNs identify a cluster of characteristics, including publisher, country, and format, so even with the same title, your new ISBN will identify a unique product).

Hi, Paula,

Thanks for the kind words! I’m sorry to hear about your difficulty with your former publisher, but glad that you did eventually get it resolved.

Re: Amazon refusing previously published titles…I’ve never heard that that’s the case, and I know of many, many authors whose publishing contracts have expired or who have terminated their contracts and have re-published their books via KDP or Ingram Spark.

I know that Amazon is extremely opaque about its reasons for doing anything, and sometimes innocent books get caught up in one of its algorithm sweeps for plagiarism or other problems. It’s possible that if a previous version still appeared to be available for sale (if your former publisher didn’t take steps to notify retailers that the book was “out of print”, for instance), there might be an issue, with the algorithms confusing that with copyright violation. But I’m not aware that simply having previously had a publishing contract is a problem for publishing on Amazon (or elsewhere).

Victoria, I think you know how much I always love and appreciate your posts–and more than that, the work you do to help educate and protect authors. Especially in business matters, and especially in those related to something writers often want so badly as a publishing contract, I think it’s hard to stay focused on the business elements of your career. You always help clarify the issues and encourage authors to make sure they look out for their own interests. Thanks for another great post. I’ll be sharing this one, as always.

One of the clearest and most helpful articles ever published by WU. Thank you!!

Victoria, I know that such clauses can exist in the “world of ‘e'”, but after forty-six years of working in traditional publishing to see them in reality–and as subject of a cautionary post–is shocking. I mean, copyright grab? Copyright of edits? Termination fees? I’m so sorry that your post today is necessary.

There is one area of overlap with traditional publishing contracts, the business of when a work remains “in print” or not, so that rights can be reverted. You’ve explained it well. Because books are now not only physical products in stock in a warehouse, or not, the standard for publishers to meet is a sales threshold. If they’re selling the work, they’re doing their job and fulfilling the intent of the publishing agreement. If they’re not selling the work, well, there’s no longer a reason for them to retain rights.

You also nicely explain the potential trap of a “net profits” deal. At my agency, we have done a few profit-sharing deals but in the contract language we clearly limit what costs can be deducted from net proceeds in order to determine the “profit” to be split. (And 50% for the author is the only acceptable minimum.) The only allowable costs are those directly related to the production of the author’s work alone, such as outside editing, design, printing, distribution and so on. Blended costs are disallowed, such as overhead, payroll, “house” ads, publisher’s travel, etc.

One remedy for authors with an untested publisher is to limit the “term of license” to three years. So, instead of a contract lasting for the (very, very long) duration of copyright, so long as the work remains “in print”, the contract ends completely and absolutely in three years, no conditions to extend it, nothing is retained by the publisher, no automatic renewal, only a new and separate (and separately negotiated) agreement if desired.

You’re a solid gold watchdog, Victoria. Thanks.

Thank you so much, Don!

On net profit royalties…as always with addressing complex issues in limited space, some nuance is lost. I’m extremely skeptical of net profit royalties for first-time publication–which is mostly what I’m addressing in this post–largely because of the prevalence of abuse. But I agree they can be worth considering in other circumstances, such as for backlist titles being brought back into circulation…as long as they fit the model you describe: a minimum 50/50 split, and clearly stated–and limited–deductions. Some of my own backlist is with Open Road Media under a similar net profit royalty arrangement.

Victoria, Amazon is selling my books but refusing to pay me the royalties owed. In addition to this, Amazon has been issuing 1099’s on which I have had to pay income tax. Their lawyer claims that sending me 1099’s is legal in spite of the fact that they are withholding payment. Another problem I have with Amazon is every time I try to clear up the situation they send my files to England, and England claims I do not exist. I have contacted a couple of attorneys but they want retainers in the amount of $100,000 to go after Amazon.

Elaine, I’m so sorry–that sounds like a nightmare. Why is Amazon refusing to pay you your royalties?

Yeah I’m dying for an update on this question!! I can’t imagine even a too-big-to-fail company like Amazon refusing to give any explanation at all as to why they aren’t paying royalties! I am far from a lawyer though and can’t give any advice, but it sounds like England not knowing you exist probably most to do with it…

Many other clauses to look out for, among them the standard clause about indemnification (in which you protect them against any and all lawsuits against your book). Make sure the indemnification is two-way, and insert the word “reasonable” before you agree to pay their legal fees, Sign nothing that bars you from writing anything for another publisher, a clause occasionally added, and though you may have to give them “first refusal rights” on your next book, put a time limit on how long they can take to decide if they want it. Specify the terms of payment of your advance, eg, if they say the third payment is “upon acceptance,” they can stall acceptance, so specify that acceptance or rejection must be given w/i x days after your turn it in. Don’t give away subsidiary rights or accept too small a % if there’s a split. Sign nothing that forces you to seek out and pay for any permissions needed (as for your use of copyrighted quotes). They should pay for those but can deduct the cost from royalties. That’s just top of my head. Pretty sure there are others.

Really helpful. I’m bookmarking this one in case I’m ever lucky enough to get that far.

This was wonderful, Victoria. I do have a question about a red flag issue that agent Kristin Nelson has spoken of. She calls it “joint accounting,” and described it in a 2010 blog post. (https://nelsonagency.com/2010/06/one-possible-peril-of-a-multi-book-deal/ ). Basically, it happens when a publisher offers a multi-book deal for standalone books, and the advance is meant to be divided between the books. But no royalties can be earned until all books earn out their portion of the advance. She says it’s fairly standard contract language with some publishers, but her agency refuses to do it, and one can see why. I’m curious to know your take on this.

Thanks for the questions, Beth! I agree with Kristin Nelson on joint accounting: it’s definitely something to watch out for, and to negotiate out of a contract if you can. It’s exclusively an issue for advance-paying publishers, so you’re less likely to encounter it with small press contracts, where there’s often no advance, than with a larger house where advances are standard practice.

I could probably write three or four more posts on author-unfriendly contract clauses! The ones I’ve highlighted in this post are some of the most egregious (and non-standard), but there are many others. Maybe for my next WU post, I’ll do a Part 2.

Ooh, I hope you do!

Thank you for this. A question I have is about a guarantee to publish clause. Does that definitely need to be in there? If they don’t commit to publishing within a timeframe, can your book be held up forever?

Hi, Teresa,

There should always be language in the contract stipulating that if the publisher doesn’t publish within X amount of time, you can terminate the contract and revert all rights by sending written notice to the publisher. Otherwise the publisher can indeed sit on a manuscript for as long as it likes, and you have no recourse to either force it to publish or to get out of the contract.

Big publishers, which schedule pub dates far ahead, may set a timeframe of 18-24 months. For smaller publishers with smaller lists, 12-18 months is reasonable (or less–though bear in mind that a publisher that claims it can get your book out in 4 months may not be taking enough time to carefully edit or to do pre-publication marketing). IMO, anything over 24 months is too long. I’ve seen contracts that allow the publisher three full years to publish, which I think is unreasonable.

So very helpful but I do have all the problems that others have encountered and I am what is a writer who works on everything. I wrote for Amazon for small presses for the Chipmunk and all the Vanity presses. Want is there but nothing is happening.