Crafting an Unforgettable Villain: Lessons from Louise Fletcher’s Portrayal of Nurse Ratched

By David Corbett | October 14, 2022 |

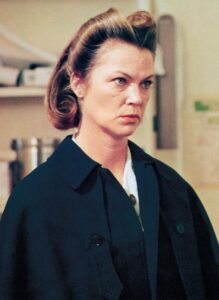

The actor Louise Fletcher passed away a few weeks ago (September 23rd), and though she had a career spanning over half a century, much of it in television, her signature role, the one for which she is most remembered, is that of Nurse Ratched in Milos Forman’s adaptation of the Ken Kesey novel One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.

Why is it that in a wide open field of other notable villains—Hannibal Lecter, Norman Bates, Francis Dolarhyde (the “Red Dragon”), Tom Ripley, Noah Cross—this gentile, soft-spoken nurse continues to represent a particularly insidious form of evil?

In a Vanity Fair profile written by Michael Shulman in 2018, Ms. Fletcher explained her unique approach to the role and shared some other insights into the making of the film. The article was at least in part prompted by news of an upcoming Netflix series, Ratched, based on the same character (Sarah Paulson serves in the series role),

The TV series purports to tell the story of how the title character came to become such an iconic embodiment of evil—i.e., it focuses entirely on events that took place before those depicted in the novel. That backstory, created entirely by the show’s writers, bears little resemblance to the character in Kesey’s novel.

To be fair, Louise Fletcher’s portrayal also differed significantly from how the character was presented in the novel, but the difference between her approach and that provided by the TV series is striking.

The TV series portrays Nurse Ratched as diabolically evil by nature—malformed by childhood trauma, hardened during service as a nurse in the Pacific theater during WW2, and progressively more unhinged as the series progresses—with the ultimate effect that of a meticulously crafted mask concealing the soul of a self-aware monster. (The TV series makes little attempt to restrain its over-the-top inclinations, to the point it often approaches grand guignol. Its showrunner, Ryan Murphy, lists American Horror Story and The Jeffrey Dahmer Story among his credits.)

The film, on the other hand, sought to temper the more exaggerated elements of the novel. Forman, a veteran of the Prague Spring and an important figure in the Czech New Wave, escaped Czechoslovakia after the Soviet invasion in 1968, saw in the novel an analogy to his own experience under totalitarianism. (Kesey wrote the novel as a critique of U.S. conformity in the aftermath of WW2.) With respect to the character in question, Forman said, “The Communist Party was my Nurse Ratched.”

Ms. Fletcher took a slightly different approach. Consumed by the Watergate hearings, she saw in Nurse Ratched a reflection of Nixon’s abuse of power, but both she and Forman knew playing the character as an idea wouldn’t work, just as they agreed the portrayal in the novel was cartoonish—in Ms. Fletcher’s words, “she’s got smoke coming out of her ears.” Instead, she focused on a simple human observation: Nurse Ratched is convinced she’s right.

She thought back to her childhood in Alabama and “the paternalistic way that people treat other people there … White people actually felt that the life they were creating was good for black people.” She saw how that dynamic translated to Nurse Ratched and the patients under her care. “They’re in this ward, she’s looking out for them, and they have to act like they’re happy to get this medication or listen to this music. And make her feel good about the way she is.”

This approach resonated with Forman, who realized that Ms. Fletcher’s Jim Crow Alabama shared many of the dehumanizing elements he’d experienced under Communism. In a 1997 interview, he said, “I slowly started to realize that it will be much more powerful if it’s not this visible evil. That she’s only an instrument of evil. She doesn’t know that she’s evil. She, as a matter of fact, believes that she’s helping people.”

By taking this more down-to-earth, human approach, Fletcher and Forman managed to make Nurse Ratched even scarier, revealing in vivid terms how good intentions do indeed pave the road to Hell.

In creating the character’s physical nature, Ms. Fletcher asked celebrity hairdresser Carrie White to come up with something unique, and boy did she. “[T]he hairdo, the dress, everything I had on under it that I wore to be the way she was, the white stockings and the undergarments,” all underscored how the character was “stuck in time.”

Photo Credit: Peter Sorel/©United Artists/Photofest

She also created a detailed backstory for the character, but she kept the details a secret for the rest of her life, except for a few she shared in the Vanity Fair profile:

“She had sacrificed her life for other people. She hasn’t married, hadn’t done this, hadn’t done that, and was self-sufficient on her own leading this life, because she dedicated her life, her earlier life, to other people who needed her.”

She also created a first name for the character—Mildred—and decided that she was a 40-year-old virgin and that she was “very turned on by this McMurphy guy [the Jack Nicholson character].” That might be the most marvelous insight of the entire interview. It underscores just how central control (and power) was to the character—that sexual attraction never leaked out into the open, except in her determination not to let McMurphy get the better of her.

Film critic Pauline Kael wrote of Ms. Fletcher’s portrayal, “Nurse Ratched’s soft, controlled voice and girlishly antiseptic manner always put you in the wrong; you can’t cut through the crap in her—it goes too deep. And she’s too smart for you; she’s got all the protocol in the world on her side.”

Interestingly, the director at first didn’t see the genius of Ms. Fletcher’s approach. In his autobiography, Turnaround, Forman wrote, “In the book, she is portrayed as an order-mad, killjoy harpy. At one point Kesey even describes her as having wires coming out of her head, so I searched for a castrating monster.”

One by one, the women he thought suited to such a portrayal—Anne Bancroft, Geraldine Page, Angela Lansbury—turned him down. The growing women’s movement made taking on the role of a villain decidedly less appealing than in the era of the femme fatale. But Ms. Fletcher, who knew about Forman’s need for someone to play the role, pursued it relentlessly, until Forman decided to take a chance on her. He didn’t think her “prim, angelic” manner conveyed evil at all.

That conflict revealed itself on the first day of shooting. With all this background work, Ms. Fletcher felt confident she had a firm handle on the character. But on the first day of shooting, when they were filming the scene where McMurphy enters the hospital, she’s letting him know that if does everything by the book, doesn’t make waves, they’ll get along fine. She was kind, soft-spoken, as she believed the character would be. But then she tilted her head, and Forman stopped filming. “Don’t tilt your head. It looks weak.”

For several days, that direction stifled her—she called her husband and told him she was going to get fired because, “I’m in a vise now, and I can’t move my head.”

The problem was in how differently the actor and the director perceived the character’s strength. Forman worried that if a gentle, soft-spoken Nurse Ratched wouldn’t be able to stand up to such a raucously unconstrained character as Nicholson’s McMurphy. After a couple days, however, Forman realized his mistake and told her to go back to portraying the character as she saw fit.

The Takeaway

What can we learn from all of that? Allow me to suggest a few lessons.

To make it real, make it personal. Louise Fletcher explored her own feelings and her own experience to flesh out her understanding of how and why Nurse Ratched behaved as she did. Explore your own beliefs, experiences, and emotions in identifying what you see as harmful, cruel, destructive, brutal, manipulative, and so on.

Recognize that evil almost always centers on power. That pursuit may be through ruthless violence, cynical manipulation, blatant corruption—or strict obedience to the rules and an unflinching sense of propriety—but evil reflects an individual’s inability to accept anything but a dominant role among others. Equality is for suckers. Or, put differently: the right people are in charge for the right reasons.

Identify how the character validates her pursuit of power. Remember: justify, don’t judge the character. How is she “the hero of her own narrative?” Do they believe the strong get what they want and the weak settle for what they can have? Do they believe that someone of their station is not bound by the rules in the way lesser people are? Or are they, like Nurse Ratched, doing their best to help people? Perhaps even ask how the character believes they are a victim rather than an instrument of evil.

Examine how your character’s perspective reflects a larger worldview. (Nurse Ratched’s conviction she is helping people is rooted in the patronizing behavior of whites toward blacks in the Jim Crow south; it also echoed Forman’s experiences under Communism.)

Explore how your character is an instrument of a larger evil. This grows out of your responses to the previous two prompts. For example, Nurse Ratched does not see herself as evil, she thinks she is helping people. But that reflects a world view that “normal” people like her are obliged to control those who won’t fall in line. Your character may be aware that they’re part of a larger evil—a soldier in an organized crime family, for example—meaning his justification for his wrongdoing will be a reflection of the good he believes he’s serving through his allegiance to this larger entity.

Don’t neglect the character’s physical nature. Ms. Fletcher’s attention on how Nurse Ratched looked and dressed and carried herself were essential to her portrayal, and reflected the constrained, stuck-in-the-past elements of her character. How does your character’s choice of clothing, manner, attitude—even furniture, automobile, favorite dining spots—reflect how she justifies her perceived role in the world?

Don’t be afraid to go against type. Not all monsters announce their presence with a roar. Contradiction is always compelling, and portraying a character who harms others in a way that suggests instead a mild, considerate, thoughtful nature only intensifies the shock when they act in accordance to their absolute need for power.

Resist the urge to explain. The fact Nurse Ratched is a 40-year-old virgin secretly lusting after McMurphy, along with the untold number of other backstory details Louise Fletcher declined to disclose, all revealed themselves not through explanatory flashbacks or a “Let me tell you something about myself” monologue but through behavior. I’d argue it’s precisely that lack of explanation that makes her all the more terrifying.

Do you have a “Nurse Ratched” in your WIP? How so? How has your characterization echoed some of the decisions Louise Fletcher made in her approach to Nurse Ratched?

If your opponent or adversary is different than Nurse Ratched, how so? How have you gone about exploring the ways they justify what they do? Does their moral perspective reflect a larger worldview? Do they embody a larger force, stand in for an institution, or serve a larger entity?

How have you approached their physical nature?

Have you gone against type and made their manner at odds with their intentions?

How have you examined your own beliefs, experiences, and emotions to flesh out how your character inflicts harm on others?

Chuckling as I read your post. You got it.

From the first review for NETHERWORLD, the second book in my mainstream trilogy:

“…in this second book, I found myself fascinated by Bianca. She is scheming, two-faced and quite ruthless, the obvious villain, and yet she is not at all two dimensional. Instead, the author has given her a past, a past that hints at why she has become the person she is…and why she believes her actions are justified. She really doesn’t see herself as the villain at all.

Unfortunately, Bianca’s actions embroil the other two characters in a situation from which there seems to be no escape, and I kept muttering ‘don’t do it, don’t do it!’ for much of the story…”

Bianca’s motto is “Why NOT me?” And she looks for signs she is the chosen one, not just America’s Sweetheart, and reigning Hollywood princess. Of course she finds them, proof that what she wants to do is right – and he’d thank her for it if he knew. But she has the sense not to tell him.

Villains are key, as James N. Frey tells us in THE KEY – How to write damn good fiction using the power of myth.

It’s a lot of fun to deliberately use ‘myth’ in a modern story.

I know Jim Frey. We met at the Squaw Valley Writers Conference, and he’s a wonderful teacher and his books are excellent writing guides. (He’s also a real character — very funny, suffers no fools.)

So, judging from the excellent review (congratulations), I’m guessing you decided to provide, rather than withhold your villain’s backstory — and it worked. That’s always the question — how much to show — and the answers vary from Richard III (next to nothing) to Francis Dolarhyde (damn near everything).

From your comment I’m guessing Bianca was in some way based on a mythic character. Which one?

As always, thanks for chiming in, Alicia.

Bianca is, of course, The Evil One, but I based her on what the story allowed and needed, not a particular mythological character.

However, Frey says, “The role of the Evil One is to hatch an evil plot and carry it out. The Evil One provides most of the tests and trials of the hero.” And “…the Evil One is also an evil presence that creates a sense of menace” – which is what my reviewer was picking up on that made her mutter “don’t do it.”

In many stories, the villain/Evil One is crucial to the events of the story happening NOW, or happening at all – humans are procrastinators, and don’t get around to many things until they are forced to. Bianca definitely is the reason things happen NOW – because they are in HER plan. And her timing is critical – I spent many months in research and with calendars.

These things are truly in the mythological background of those of us who are read in the classics as part of a basic education (not in any major depth) – because I had Bianca completely set up and to rights BEFORE I read Frey; but he sure provided a lot of good solid tweaks. And understanding.

David–thank you for another post to print out and read again. You’ve used an extended analysis of a fictional character–Nurse Ratched–to educate us in how to deepen character, how to counter the pop culture forces at work that lead to cartoons and over-simplifications. I haven’t read/seen the story in a very long time, but your post takes me back. What is it that makes Fletcher’s character still live in memory?

I think it’s because the actor (and finally the director) understood what a mistake it would be to chew the scenery, to go for grand guignol as the TV series will probably do. Fletcher’s calm voice and icy aspect make her all the more demonic.

I have a character that bears some resemblance to Nurse Ratched (a brilliant name, by the way, thank you Ken Kesey). She is a tortured soul whose terrible early experiences have licensed her to be a monster as an adult. She’s convinced she is protecting and nurturing a superior being–her child–in a corrupt world. She is successful in both the science side of business, and in academe, which also serves to strengthen her sense of superiority. But in a variation on Nurse Ratched’s attraction to McMurphy (leading her to punish him for causing such unruly feelings), my character acts not from a wish to protect and nurture, but out of jealousy at seeing her daughter on the cusp of a happiness that could never be achieved by her mother.

Unlike the film, my story isn’t informed by the bigger picture–Russian invasion of a neighbor, or Watergate, or racism in Alabama. Only by a one-sided condemnation of modern society.

Your post has helped me to see something of my own making in the light of one of the few movies that I think is better than the book. And I thank you again.

Thanks, Barry. I’m sure there will be plenty of scenery-chewing in the series but after the first episode I just thought, okay. Enough. Not that the cast isn’t excellent: Sarah Paulson (an actress I admire and whose portrayal is strong, just different), Judy Davis, Vincent D’Onofrio, etc. The approach though very much goes for effect, not psychological, moral, or sociological nuance, which the film addressed brilliantly (imho).

I love how you’ve crafted your character. Much like Nurse Ratched, the background of self-sacrifice, rather than ennobling the character, has hardened them, fostering resentment and a vengeful victimhood that says, “I paid, now it’s your turn.” Gee, don’t see much of that in the world, do we?

And though NR echoed certain larger themes, I don’t mean to suggest that’s essential. Just interesting. No checklist of things to think about a character should ever suggest that all the boxes HAVE TO BE checked. Sounds to me your villain was plenty convincing as is.

There aren’t enough lectures on crafting villains. Thank you for yours. It’s been years since I watched the movie yet your analysis brings all of it to the fore. I do have a Ratchet in my historical and he knows what he’s doing is wrong, but he enjoys the power that he wields. Like a fractal, I’ve set the domestic violence at a period during societal violence as well as state-run violence. And of course, the powers that be said it was for the good. It’s been quite interesting to see the parallels now.

Thank you, Vijaya.

Great exploration, David, and an even better breakdown of how to bring a character there.

I think much of a villain comes down to one test: do they seem *inevitable*? Have they moved beyond cartoony surface and stock motives to the point that their drive starts to feel real, whether it’s an everyday horror or a “larger than life” but compelling passion?

If you ask “would a person like this *have* to get in the hero’s way?” the answer has to be

HELL YES!

That’s an excellent observation, Ken. It reminds me of Lajos Egri’s admonition (echoed by Jim Frey in his novel-writing guides — see my response to Alicia’s comment above), that the protaoginst and the opponent have to be locked in a Unity of Opposites, a moral, psychological, emotional, situational or existential deadlock that can only be broken by one of them prevailing at the expense of the other.

Terrific post, David. Villains are as vital and central to a story as protagonists. And sometimes the villain is our own darker side. I love your in-depth analysis here. So insightful and USEFUL. Thank you!

Thank you for the kind words, Kathleen. (And “useful” is the point, no?)

Thank you for another fabulous post. I love the deeply afflicted protagonist and have now published the second book in the story of Nico Romero. In keeping with your terrific post, I’ve never diagnosed him. Instead, his troubled psyche is revealed in the charismatic and manipulative behaviors he uses to compel people. He needs their devotion to define him. And as a healer, he expects it and believes himself worthy. The problem is untangling from his inexorable bond and reclaiming your life. Evil? Codependency? Feeling sorrow for the painfilly afflicted soul, or the desire to murder him? Readers choice.

That sounds like an intriguingly complex character, Luna. And letting the reader decide how to feel about him, rather than deciding that for them, sounds like a wise choice.

Hi David, I’m focussing on your question: how have you approached their physical nature? My character, who supplies a force of evil in the novel, was raped as a child. Physically and mentally her life beginnings make it difficult for her to STAND TALL in the world. There is no father, the mother is a prostitute. Physically, she moves through life with her hair shadowing her face, her body bent to the work she is doing. Physically and mentally she is handicapped, burdened, until she kidnaps a child, struggles to be kind to that child, and thus tries to consider herself a mother. I walk a very fine line when this character forces a haircut on the child. Maass told me to let it rip…we will see what others might think. Great post.

Wow, Elizabeth. That’s some seriously heavy lifting. But I think you got the physical details right. So many abused children almost try to make themselves disappear, like they’re afraid, if they’re seen, they’ll just be targeted.

I hated haircuts as a kid. I can only imagine how bad the one you’re writing will be.

I’ve never watched or read any of the works containing Nurse Ratched, but your discussion of her here was fascinating, and left no confusion about why she’s so compelling across so many different forms. Thanks for the fun and thought-provoking deep dive.