How Long Should Your Book Be?

By Dave King | July 19, 2022 |

Ruth was reading an old Susan Howatch novel on her Kindle, which tracks the percentage of the book you’ve read without bothering about page numbers. After reading for a few days, she noticed that she hadn’t made much of a dent on the percentage. I asked the internet and found that the paperback of the novel had been more than 1100 pages long.

I’ve always argued that a manuscript should be as long as it needs to be to tell its story. A lot of successful books – Jonathan Livingston Seagull, or The Bridges of Madison County spring to mind – are not much more than novella length. The Lord of the Rings, broken into three books but really a single, continuous story, clocks in at 1086 pages, not including the appendices. None of them feel too short or too long.

Besides, trying to force your story to fit a predetermined page count because you think that’s what the market demands is almost always a recipe for disaster. Adding or cutting material just for the sake of adjusting the length leads to either in gaps in the narrative or padding that drags the story down. This is not to say that all first drafts are the right length out of the gate. Sometimes stories do drag and need trimming to flow better. Others are too thin and need subplots built up or more details on the characters’ internal lives. But these are changes made for the sake of getting the story right, not to fit the market.

So how do you know whether your odd-length manuscript is just what it needs to be or is too bloated or anemic? Successful novella-length novels usually succeed because they are centered around a character development or story point that didn’t need a lot of pages to convey but that carries the emotional weight of a full-length novel. Readers can finish them quickly and not feel underfed.

I’ve written before about Ted Chiang’s “Story of Your Life,” the novella on which the movie “Arrival” was based. In the story, Chiang gives a sense of what it would feel like to experience time all at once rather than in linear sequence – and only reveals that that’s what he’s doing at the end of the story. That’s enough masterful storytelling for a novel, but adding more material would have distracted from the central point. It is a short book that still feels like a long book.

Extremely long novels also have a couple of features that make readers willing to put up with four-digit page counts. The Lord of the Rings creates a complex world with several independent cultures and thousands of years of backstory. It takes time to get all that across. The same is true of massive, multigenerational works, like the Susan Howatch book Ruth was reading.

Long novels often work two or more different complex threads at once – effectively telling a single story through several different, interwoven novels. After The Fellowship of the Ring, Tolkien’s narrative splits up into at least three threads – Frodo, Sam, and Gollum making their way into Mordor, Pippin and Merry rousing the Ents, and Aragorn heading down to defend Gondor. These threads cross occasionally and come together at the end, but any one of them could make a standalone novel. And then there’s “The Scouring of the Shire,” a short story appended to the end.

Abraham Lincoln, our tallest president even without the stovepipe hat, was once asked how long a person’s legs should be. Lincoln said, “Long enough to reach the ground.” The same sort of thing is true of manuscripts. As long as you’re sure you’re telling your story the best way possible, just let your manuscript be as long as it needs to be.

So what other reasons can you think of for a book being a “non-marketable” length? What odd-length books have you read? Why have they worked?

[coffee]

That said, in my experience it’s a rare manuscript that couldn’t lose a couple of thousand words. The longer it goes the more that can be true. Tightening generally is good, or at any rate I have never once thought to myself, “Gee, I wish this manuscript had a lot more words…”

Would you agree, Dave?

I would. Strunk and White’s rule 17, “Omit needless words” still holds as good advice.

I think that some of Alice Munro’s stories are really novellas or even novels, so much does she pack into each story, and so deeply can the reader sink into the story as into a novel.

That’s it, Anna. Shorter works feel satisfying because they pack the emotional punch of longer works.

But then they’re over with too quickly…

That’s my main complaint about short stories.

Yessss! Alice Munro can write a novel in 20 pages. “Friend of My Youth” is TWO novels packed into a short story. Awesome writer. The other Alice, Alice McDermott, my all-time favorite, is a master of long short novels. “Charming Billy” is an entire family saga, three generations in 243 pages.. “My Name Is Lucy Barton,” by Elizabeth Strout, is another amazingly complex and deep short novel that the reader can dip into time & again, coming up with a different treasure each time. I wish I could do that!

Dave: Thanks for giving the best answer to the question of length: make it as long as it needs to be–for that part of the market the writer wants to reach. By temperament as a reader, I steer clear of long books. I think it has to do with my memory: I need what starts with momentum and interest to move to a resolution that doesn’t oblige me to remember too many events and characters. I know this point of view is at odds with a great many readers, but it’s one that also fits with me as a novelist. I’m not a sprinter–that’s for short story writers. But neither am I a long-distance runner. For some reason I don’t understand or really want to, three hundred pages, give or take, is the “right” length for me as both a reader and writer. Maybe I’m just hard-wired with three-act structure. Thanks again.

It sounds like you’ve got your groove, which is the best reason to write the length you write. Not everyone wants to read (or write) multi-generational epics.

Diana Gabaldon has produced more than a few longer novels. She can get away with it. Today’s new writers cannot. Unless you self publish, you’re at the mercy of an industry that insists on lower word counts. Which, in my opinion, sucks. I have indeed wished for a few more chapters in books I’ve read. I felt the story cut short what readers needed to know. Many of my book club friends agree. That we were cheated in the protagonist’s past or future. Losing myself in a story, I feel ripped off when I get to end, hoping there’s a sequel! In a skilled writer’s hands, book length should be their call. Stop forcing shorter word counts. Stop assuming what readers want.

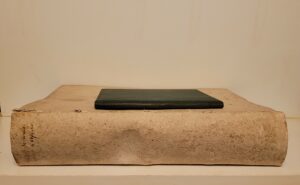

This does highlight a problem that I didn’t take the time to get into — agents and acquisitions editors do have a preferred length, especially for a first novel. Part of the reason is just a matter of physical limitations. Short novels tend to get lost on bookstore shelves, and long novels with traditional paperback glued bindings are hard to read without having them fall apart. Even though neither of these problems is as serious in the world of Kindle, they still affect purchasing decisions.

On the other hand, if you are trimming your long manuscript to fit the market’s expectations, you wind up with books like the ones that frustrate your book club. Writers who write long or short novels may just have to adjust to the fact that they’re going to be harder to sell.

Pamela, there are price point considerations, too. Above 120K words, a hardcover starts to cost $30 and more, and bookstore customers resist when it’s a writer they don’t know, such as a debut author. You can blame publishers but it’s plain consumer behavior, really. Self-published e-books don’t have that pricing issue, of course, but the trade-off is visibility. It’s an author’s choice which path to take.

Length gets a bum rap sometimes. “Omit needless words” is such seductively simple advice, for all that it takes sweat to follow, and writers and especially love to say they’ve refined and purified a story.

Still, the other side of that is the enhancement that pulls its own weight. The added wrinkle to the story that still lets the overall proportions work, or even improves them. Yes these can be risky, because they take actual creative work and can turn out to be rabbit-holes that didn’t improve the story, but that doesn’t mean some of them aren’t worth trying. It’s just easier to picture an iffy scene cut out than a new element most people *can’t imagine* yet, and that leads to the myth that cutting is automatically better than adding.

Good editing knows when to cut, absolutely. But it isn’t *always* “the first draft minus 10%.”

I certainly agree that cutting has to be in the service of the story — the 10% figure is too arbitrary.

I would like to observe (WARNING: advertisement) that one of the things independent editors can provide is the chance to put those extra words in for the sake of experiment. One of the hardest things to get right in your own manuscript is the proportion. A set of well-trained, independent eyes can spot places were you’ve given too much (it’s almost always too much) and rein you in.

If you are self-publishing a book and want to release a print edition then length can be a major issue. I recently published the final novel in a sci-fi trilogy. It was 460 pages long. In order make any profit on print edition sales I had to give it a list price of $18. The distributor and retailer get over half of that and the print-on-demand cost eats most of the rest of it leaving just over $1 for me. The longer the book the higher the print-on-demand cost which drives up the list price and hurts sales. I actually make more per $2.99 eBook edition sold.

Duncan, that’s kind of what Don was talking about above — price point matters to marketing. You can avoid the problem by e-publishing, of course (bits are cheap), but ebooks haven’t exactly taken over the marketplace the way they were predicted to.

The reason for a longer book is given by Donald Maass: because it takes more words to make the improbable possible, if you have that kind of story.

Chapter 6 in The Fire in Fiction is entitled Making the Impossible Real. All you do when you try to skimp is make it easier for the reader to stop suspending disbelief.

Dave, good post. My debut historical fiction book was 458 pages. I kept apologizing on marketing blog posts for the length, saying there’s romance and music to balance the history. Readers were okay with the length and wanted to know – what happens next? I decided on 260-300 words for the sequel. There will be less figuring out how to include real history and imaginative history for one character. And more straight forward history about real 1960s events and character’s reaction and place in them. I’m already getting rid of unnecessary words, and getting into action and reactions. 📚 Christine

That makes sense. If you’ve already established both your world and your characters, you don’t need to repeat the material when you tell the second story.

Love this article. I often read a book and find myself wanting more; rarely do I wish there was LESS. That being said, I do find myself only able to read short books lately–novellas, in particular. Curiously, this intersects with the completion of my first long manuscript (draft one). As someone who formerly only wrote short, now I find myself with a manuscript that’s too long … even as I read novellas and shorter novels. I understand the economic factors that come into play, but I still wish the publishing industry would relax a bit when it comes to length.

There used to be venues for modest-length manuscripts. The Science Fiction magazines I read years ago always led off with a novella, followed by a series of short stories. And mainstream magazines like the Saturday Evening Post or The Atlantic sometimes published novella-length works by popular authors. I think some of those venues are still out there — the Sci-fi magazines are still in print, and a lot of anthologies publish intermediate-length works. But novellas aren’t exactly accepted by mainstream presses.

I gravitate toward reading novellas now as well as write them. I love tight writing. I tend to get bored and start skimming if a book is too wordy. There are a few long books I really liked and they did have enough going on where they needed the length, but when I download books I mostly look for under 200 pages. I have been writing for years and 7K words used to be considered a novella and a few K over that moving into novelette territory which, by the way, I don’t hear that term anymore. Now 7K length MSS are called short stories. My books or whatever you wish to label them often average about 25 to 30K words. Some places will not let you advertise if they are that short which I think is missing the boat. I can’t be the only one who prefers shorter reads and why should they care if the customer is willing to pay the same fees?

You’re right, I haven’t heard “novelette” in years, though I do remember a New Yorker cartoon referring to a “Novellini.”

And you’re also right that it makes little sense to restrict length (in either direction) in the era of epublishing — the costs of exceptionally short or long books were mostly production costs.

Still, there may be an economic line of thought. Full length ebooks by beginning writers tend to sell for about $0.99. If that’s the cost of a 300 page novel, what’s an appropriate cost for a 90 page novella? $0.50? $0.25? This ignores the fact that you can often get a better reading experience from 90 pages than from 300, but the market is a fickle place.

SFWA (Science Fiction/Fantasy Writers Association) still uses the term “novelette,” which is shorter than a novella. Their categories for Nebula Award consideration are: a short story must be under 7500 words, a novelette is 7500 to under 17,500, a novella is at least 17,500 but less than 40,000, and a novel is 40,000 and above.

Personally, I think a novel should be at least 60K; I would put 40K in the novella category.