Reading Between the Lines: The Predatory Contracts of Serial Reading/Writing Apps

By Victoria Strauss | June 24, 2022 |

Serial reading/writing platforms and apps aren’t new. Wattpad is probably the best known; others include Radish, Webnovel, and Kindle Vella.

In the past couple of years, though, there’s been major proliferation in the serial reading/writing space, with multiple companies launching mobile apps: Goodnovel, NovelCat, SofaNovel, FameInk, Hinovel, NovelPotato, Novelstar, Fizzo, just to name a few.

Based primarily in Singapore, Hong Kong, and mainland China, these apps host enormous numbers of mostly English-language serialized novels in almost every genre you’ve heard of (and some you haven’t). Novels are published chapter by chapter, with the first few available for free and readers buying “coins” or tokens to unlock the rest.

What’s the appeal for writers? Monetization. Benefits include a share of reader-generated revenue, along with a variety of one-time or repeating cash payments (for instance, Novelbee offers a signing bonus, an updating bonus, a completion bonus, a renewal bonus, and an advance/buyout payment). And it’s not just about the money. The apps also hold out the promise of exposure, reader feedback, promotional support, and guidance from editors. “We Nourish New Shining Stars,” Hinovel promises.

Despite publishing almost entirely in English (and featuring mostly white European faces on book covers), the apps recruit internationally. Novelcat, for example, describes its Writer Benefits in Bahasa Indonesia, Vietnamese, Hindi, Tagalog, Portuguese, French, German, and Spanish in addition to English. Editors, aka recruiters, who look to sign completed and previously published books as well as works yet to be written, employ aggressive tactics, including soliciting writers on Wattpad, messaging them on Facebook, inviting submissions in writers’ groups, and emailing out of the blue. If you’ve self-published, or published with a small press, you may hear—or may already have heard—from a serial reading/writing app.

So why do the apps loom large on Writer Beware’s radar?

UNPACKING THE PROMISES

What’s not always completely clear in recruitment ads and emails, or on the apps’ websites, is how conditional many of the “writer benefits” are.

The full range of financial rewards, for instance, may only be available for exclusive contracts, with many of the income options off the table for non-exclusive agreements. Benefits may be further restricted by limited availability (you may only be able to claim monthly update bonuses twice, for example) or by requiring grueling benchmarks in order to claim them (producing 60,000 words or more monthly, being “absent” no more than two days per month). As for a share of reader income, that may only be available for books that are designated as “premium content”—something that’s entirely at the apps’ discretion, and is not necessarily guaranteed.

Many apps promise editorial guidance–but the people functioning as editors are recruited in the same way as authors, and remuneration isn’t exactly princely. iStory, for example, provides editors with a small monthly cash payment plus a 10% share of reader revenue from the authors they sign, but they get paid only if they fulfill recruitment quotas. I can’t see a lot of credentialed professionals signing on for that. (I’ve gotten reports from a number of writers who’ve had poor editorial experiences, including being berated for for not posting enough content, being pressured to insert erotic content into their books, or being ghosted by their editors.)

Some apps tease exciting-sounding PR: social media promotion, mainstream media advertising, featured placement within the app. But those perks typically go only to the writers who rise to the top with the largest number of reads. The rest must compete for readers not only with thousands of other authors on the app, but with tens of thousands of writers on the many similar apps that also offer serialized genre novels. In such a crowded, competitive space, exposure and audience-building are likely to be the exception, not the rule.

And then there are the contracts.

PREDATORY CONTRACT TERMS

I’ve seen contracts from a variety of serial reading/writing apps, both exclusive and non-exclusive (and have written about a number of them on the Writer Beware blog). Without exception, they are lengthy English-language documents dense with legalese and confusing terminology. (To give you a sense, here’s the non-exclusive contract offered by Popink.) If they’re cumbersome to slog through even for someone like me, with years of contract evaluation experience, they must seem like gibberish to many of the writers recruited by the apps, who are often very young or speak English as a second language.

And it’s important that writers understand what they’re signing up for, because app contracts can include seriously author-unfriendly language. Here are some of the most common issues I’ve seen.

Excessive grant terms. Very long contract terms are a feature of many app contracts, anywhere from 10 years, to 20 years, to (most frequently) life-of-copyright. In internet time, even 10 years is an eternity; there’s no reason in the world for a publisher to hold rights for so long, especially for works that aren’t being promoted or aren’t getting much reader attention. A fixed-term contract for digital publication shouldn’t extend beyond seven years, tops.

No or very limited options for termination by the author. Many of the app contracts I’ve seen are “irrevocable”: writers have no right of termination at all. For contracts with lengthy grant terms—especially life-of-copyright—this is really problematic: if your work is languishing at the back of the app’s catalog with zero discoverability, you should be able to terminate the contract and move on.

Other contracts allow for termination only under very limited circumstances, such as breach by the app, or make the process overly complicated or financially punitive. For example, Goodnovel allows authors to terminate 36 months after publication, but they must pay back all the money they’ve received to date, plus triple or twenty times (depending on total income) any earned royalties or revenue share.

Non-exclusivity limited by permission requirements. The contract may claim to be non-exclusive, but if you want to publish your work elsewhere—which should totally be your right under a non-exclusive contract—you cannot do so unless you get the app’s permission (and there are penalties for breach—see below).

Excessive claims on additional or future work. In many app contracts, signing for one work actually means signing for many. For instance, here’s Goodnovel (“Licensor” is the author):

And here’s Novelcat (Party A is Novelcat, Party B is the writer):

Net profit royalties. Some app contracts promise high royalty or revenue share percentages– 50% or even more. Not so fast, though: payments are nearly always based on net profit, with channel fees, operating costs, promotional costs, production fees, and more deducted from actual revenue before the author’s share is calculated.

Here’s the list of deductions made by Bytedance’s serial reading/writing app Fizzo:

Your book would have to be generating a pretty big chunk of change on a regular basis for much revenue to survive all those deductions.

Waiver of moral rights. Several app contracts I’ve seen require writers to waive or sign over their moral rights. Moral rights—which aren’t recognized for written work in the USA, but are important in much of the rest of the world–include the right of attribution (the right to have your work published with your name) and the right of integrity (the right to protect the work from changes or additions that would negatively affect it or you). You should avoid publishing contracts that require you to give those rights up.

Gag clauses. Many of the app contracts I’ve seen include language barring writers from speaking or writing about the app in a way that the app deems to be negative or disparaging. For instance this, from Dreame:

If regarded by the app as a breach of contract, violating this clause could bring punishment.

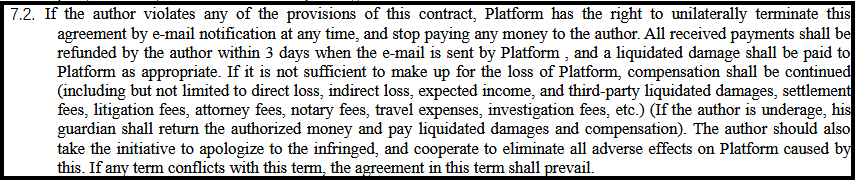

Financial penalties for breach. Not all of the app contracts I’ve seen include financial penalties for author breach. But those that do impose a serious potential hit, from fees of $1,000 or more, to reimbursement of all income received plus double or triple that amount in “liquidated damages”. This is from Owo Novel (and incidentally suggests how willing some apps are to sign underage writers):

The app contracts that I’ve seen define breach in various ways, from violating typical author warranties (such as that your work hasn’t been plagiarized), to submitting work the app deems unacceptable, to failing to “uphold the reputation” of the app by writing or speaking about your experience, to all of the above.

I have no idea how often or how aggressively the apps follow through on these penalties—but one of the first principles of evaluating a publishing contract is to understand that if it can happen, it may well happen. Never assume that a clause in a contract won’t at some point apply to you.

CONCLUSION

I should stress here that each app offers more than one type of contract (exclusive, non-exclusive, new work, already-published work), that I haven’t seen all available contracts from every app I’ve analyzed, and that not all the app contracts I’ve seen include the kinds of problematic clauses explored above.

But I’ve seen enough to know that author-unfriendly language is common–and that the often very-inexperienced writers who accept these contracts don’t understand them. For instance, I’ve heard from writers who signed an exclusive contract with one app, and later signed with another app for the same work, not understanding that “exclusive” means “can’t be published anywhere else”. I’m also, increasingly, hearing from writers who are waking up to the much-less-rosy-than-advertised reality of the apps’ monetization promises.

As a career-starter, serial reading/writing apps are, at best, a dicey proposition. At worst, with contracts full of the language I’ve highlighted in this article, they are predatory. Still, if you just write for fun and can produce a lot of words quickly, you probably won’t lose much by publishing on a serial reading/writing app. That’s possibly also the case if you have a completed trunk novel, or a novel you published years ago and wouldn’t mind putting out there again, even if reader attention turns out to be low (though be aware that you’ll be in company with a lot of really poor-quality content, as you’ll see if you spend any time sampling the novels on offer). You may also be able to maximize even stingy financial benefits if you publish on multiple apps.

Regardless, it behooves you to fully understand what you’re signing up for, and what impact the contract terms could potentially have on you. Remember also that your goals may change. One of the saddest stories I’ve heard is from a writer who began writing on one of the apps as a lark, but over the course of creating their novel became more serious about writing, and now wants to take their book off the app, revise it, and publish it conventionally. The app’s grant term is life-of-copyright with no provision for author termination, but the writer requested termination anyway. The app refused.

Have you been contacted by a serial reading/writing app? Have you ever published work on an app? What was your experience?

Yipes!

Thank you for summing these up so well, Victoria. Publishing always has its cutthroat side. I see questions about a number of these services all the time, and now I know just what to send those people to.

There’s one other case I’ve just heard of, with one of the “well-known” services you mentioned at the start. There’s currently a kerfluffle about Kindle Vella, that its terms could be read as forbidding any material that’s taken out of Vella from being republished in more than one form — as in, not in a book and then in a collection. Amazon’s come under fire for that and will probably be changing it, but right now it still seems to be in effect.

Hi, Ken,

Can you point me to some of those discussions about Kindle Vella? I’m aware of that restriction, but would like to see what people are saying about that. Thanks!

The key phrase seems to be on the KDP guide page https://kdp.amazon.com/en_US/help/topic/G3DJY2Z5WSX5U6WL where it says “A Kindle Vella episode may only be republished in one book or other long-form format.”

The question seems to be whether that “republished” refers to other uses while it’s on Vella, or if it’s supposed to be a permanent limit on anything that’s been in there.

The current debate is at https://www.kdpcommunity.com/s/question/0D58V00006aVPADSA4/vella-longform-box-setomnibus-policy?language=en_US&fbclid=IwAR2N3iQupA6RoCceZZ0gojxyFFJF-PjDcNd8fCvau6_nI5MyuN8Jg83LTIo

This is appalling. Thanks for your constant vigilance in our field, Victoria. I’ll be sharing with my FoxPrint Editorial audience of authors.

Not sure it’s one of those, but I keep receiving emails (that I pointedly ignore) from Webnovel’s various people asking me to add this or that title to their app because with the rise of werewolf titles popularity I can earn 200$/m. (I’m paraphrasing)…. Note that there are no werewolves whatsoever in my books… It reminds me when Author Solutions subsidiaries trued to lure me in 10 years ago! 🙄

Thanks so much Victoria for this broad overview. Really good to know. I was once contacted by a recruiter, not having any idea of what this might be, but at the time was exclusive to kid, so didnt cross my mind to sign with them. And also, they had 10 year contract, which from the get-go I though sounded strange. Anyhow, super useful information! Thank you!!

A writer in my 6:45 am PT Shut Up and Write Online Group has been contributing to one of these app-based publishing companies for months or maybe longer. Every time she mentions it–this happens daily at our “check in” before silent writing–I wonder how I can inform the group that these services are predatory without seeming critical of this one writer, which wouldn’t be in keeping with our group’s welcoming, friendly and very supportive atmosphere. That’s my long way of saying, thank you, WU, for this column, from a major acknowledged expert, that I can share with my group and say, “here’s what you should know” about these apps. Some of the writers in my group have also expressed an interest in reading this writer’s work on the platform. That sounds supportive, as is also typical of SUAW groups. My feeling is that readers share some culpability for exploiting authors by reading work published on these platforms. Beware, indeed.

Wish I read this months back, I write on wattpad, and earlier this year, I thought to sacrifice one of my novels just to test the waters… I signed a nonexclusive with the same book on three different platforms just to see which of the platforms would be better than the other… they are all the same, lying b*stards. I’m just thankful it isn’t my best work.

But please ma’am, what platform do you recommend for a writer like me who is still navigating her way through the writing world? Do you recommend wattpad?

I have posted my books on many specialized reading platforms. When I started writing, I wrote the plots that I loved, but my books got poor responses from the readers.

Then I started researching these platforms and what tropes work on them. I am writing an exclusive with a platform that has 15-year-long contracts. The trope is that the readers prefer these platforms. The story is fast-moving and consists of mental abuse (abuse is a favorite theme of readers on these platforms. If you want to earn on this platform, the sound won’t be enough. You will need an abusive male lead and a helpless female lead.

Trust me; this book earned more in six months than the previous eight books made in more than a year (which included income from the third prize in a contest and other finalist bonuses, which amounts to nearly 1/3 of my earnings).

Write what readers love, and you can make it big. Write what you love, and you will barely earn $100 a month.

What platform is that?