Evil and ‘The Age of Madness’

By Porter Anderson (@Porter_Anderson) | March 18, 2022 |

A statue in Lviv (in western Ukraine) is shrouded in protective material against the advance of Russian troops, March 13, 2022. Image – Getty iStockphoto: Ruslan Lytvyn

Writing the Darkness

In France, Bernard-Henri Lévy is known as BHL, like a latter-day George Bernard Shaw (GBS, who we could use now).

Bernard-Henri Lévy

Lévy’s standing among the “New Philosophers” and as a humanist intellectual essayist and author, not always without controversy–which is good–makes almost anything he writes worth picking up.

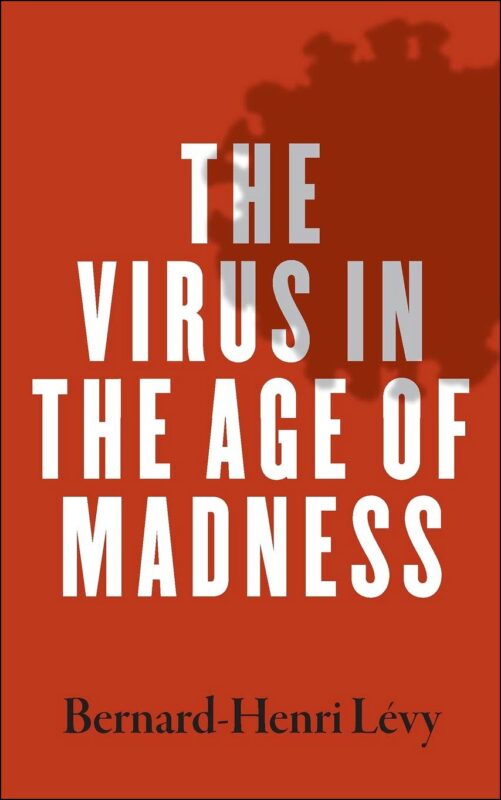

His The Virus in the Age of Madness, at only 128 pages–or just over two hours in the sane, soothing audiobook narration by Shridhar Solanki–is the one to pick up first. And not just because it’s only $1.87 in paperback at Amazon and $5.50 from Audible. (The economy of brevity is actually a thing, you see.)

What Lévy offers his fellow writers in his meditation on the coronavirus COVID-19–a now tired pandemic suddenly flaring into view under the shell concussions in Ukraine–is a chance to look at how we write about the negatives, the real negatives, the things we might call actual (not comparative) evil.

The Age of Madness. It feels like it at times, doesn’t it? Even if we could slam the brakes on Vladimir Putin’s tanks and blow-dart COVID inoculations into the necks of the entire planet’s population, we’d still be looking at an unfathomable rise in authoritarian political sentiment, and in so many countries.

Layers upon layers of challenges and comeuppances seem to await us daily.

How many times can we mutter to ourselves, “I couldn’t put this into a book, they’d never believe it”?

How many times can we mutter to ourselves, “I couldn’t put this into a book, they’d never believe it”?

This is, in fact–not just in some weird misreading of things–a phenomenal period that’s severely testing what we thought were “settled law” in the universe, understood principles, agreed-upon perspectives, facts over opinions, fairness over greed, life above all.

And not surprisingly, so much of what’s said and done and written by so many of us is evasive, ameliorative, for all the right and understandable reasons. We work to in some way to “fix” all this upended logic, all these shuddering surprises, all these frightening events.

- We want to say that a Putin can’t happen in 2022. A man who for 22 years has presided over the remnants of a formerly malign empire cannot in this day and age invade a big European democracy without the slightest provocation and (per the case being developed for the war-crimes court in The Hague) deliberately target Ukraine’s utterly innocent and courageous civilians.

- We want to say that 970,009 Americans–Americans! we emphasize in our world-famous self-absorption–cannot possibly have died already of COVID-19. Not here, not in our lifetimes, not in our country of Rockwell and Velveeta.

- We want to say that performative politicians can’t sweep whole parties into fascist rhetoric and the kind of brash denialism we used to see only in black-and-white movies about the 1930s and ’40s.

- We want to say that people would never stand up and punch out flight attendants because they askedus to follow an American—American!—federal rule and keep simple masks on their faces.

The list goes on.

And what Lévy does (Chapter 2, “Divine Surprise,” if you’d like to jump right to it) is look at how many ways we’ve tried to anthropomorphize a virus, make it something acting by or as a result of intelligence and purpose. As if it could think. As if it meant something.

We’d like to excuse the fact that so many things have gone wrong. Even more things now are going wrong, and yet even more things look likely to go wrong. He talks about efforts to promote “the notion that the virus was not altogether bad, that it possessed a hidden virtue, and that there were in this ‘war’ things to be glad about.” He gets at the the idea that “Nature is sending us a message.” That all of this can mean something.

We know why we try these things. We want to reason with a virus, to negotiate with a terrorist dictator in the Kremlin, to bring that beloved rationality of our age to bear on the Madness.

‘Humanity’s Bad Shepherds’

Lévy writes:

“Viruses are dumb; they are blind; they are not here to tell us their stories or to relay the stories of humanity’s bad shepherds; and consequently there is no ‘good use,’ no ‘societal lesson,’ no ‘last judgment’ to be expected from a pandemic, nothing to be drawn from it except simple, unemotional observations on the state of a health system (for example) and the fact that we never spend enough, anywhere, for research teams or hospitals.”

His book came out before Putin’s unforgivable savagery in Ukraine. But Lévy still would say the same. Putin’s stunning Stalinist rants that he thinks somehow support his obscene efforts to re-Sovietize sovereign nations has no actual rationale, no basis in logic, no grace of reason.

It’s dumb evil, as are viruses.

Provocations graphic by Liam Walsh

And my provocation for you now is a question.

How good are we at facing the fact of dumb, unpardonable, unredeemable, unreasoned evil? I’ve discovered that I’m terrible at it. I actually think that the citizens of our age on Earth can argue our way out of bad experiences–when there’s no one on the “other side” to argue with except aerosolized viral particles and grotesque, vulgar dictators.

Lévy mentions Albert Camus at times, of course. What he helps you remember is that Camus was somehow in touch with the fabulous, shimmering inexplicability of a plague. He could tell that it actually meant nothing, even as everyone wanted it to mean something, anything.

To know this, to know evil for what it is–the inchoate nightmare you cannot talk your way out of–is to be braver than many of us find the strength to be each day.

And this is why we look at our Ukrainian sisters and brothers with such profound admiration.

They do know what Camus saw. They know what Lévy is telling us. Evil is. It just is. The hope is in how we respond, not in obfuscating the terror. The term Ukrainian may someday come to mean a type of character who knows what evil really looks like–and who can keep fighting, but with clear eyes and stunning courage when a gaze of such darkness descends on us.

They’re lucky to have Volodymyr Zelensky, of course. We all are. But even he doesn’t try to tell them, or us, that some deity has provided this ordeal as a holy test, a message.

He just tells everyone to keep fighting, to help more.

In your writing, do you find yourself (as I do) looking for “ways out” of darker elements in your stories? Is it that “hopeful” impulse that drives us to want to water down the mindless danger of something, to make it negotiable? Does it work? Really? How do we find the Camusian grace to know our own humanity without mythology when the bombs and latest variant surges arrive?

Update Saturday: I’m en route Bologna to cover the first international publishing trade show of the year, so running late on getting back to responses. More to come, as transatlantic wi-fi permits. Thank you all for your comments.

Evil. Such an old-fashioned force. Kind of like an old character actor in a retirement home. He had a great run being bad but then some director went and created his origins story.

Turns out that Evil was merely merely misunderstood. He had trauma in his childhood. PTSD. Would have been better if he was in the grip of narcissism, you know, one of those few maladies that remains unforgivable.

Fully explained, Evil could no longer get work. Washed up. “There aren’t any parts for you anymore,” his agent told old him over the phone from Palm Springs. “Relax. Enjoy your retirement.

Evil spends his days playing bridge (at which he cheats), shuffleboard and watching reruns of shows on which he had bits. He has no visitors. Shame.

But here’s the thing. He doesn’t die. He’s just waiting for The Call. His comeback. When will it come? And from whom?

Exactly, Don. :)

The childhood trauma (and narcisissm is always better).

I always laugh at the endless crime-drama episodes about the inspector who is “coaxed out of retirement for one, last, devastating case that will cause him to question all that he holds dear.” They must have the posters printed up already, just add the new title and the actors’ names.

And yes, this one never retires. He’s baaaaack.

Just when we thought it was safe to live a modern life. :)

Thanks much, and hope you’re doing well, my friend,

-p.

On Twitter: @Porter_Anderson

As we have seen, Evil has answered The Call. Furthermore, he now has the ability to bilocate. As we can see.

Anna, keep seeing. And make sure it’s your sight, not someone describing for you what you see with “your lyin’ eyes,” as the saying goes. Clear sight is what we owe our readers, in whatever genre we work.

Thanks

-p.

On Twitter: @Porter_Anderson

I don’t know, it seems to me he’s like Betty White: he’s never out of work. But unlike White, he never is retired by biology.

Barry, how I’d love to see Vladimir Putin locked in an elevator with Betty White for all eternity.

A ‘Huis Clos’ even more fabulous than Sartre imagined for us.

-p.

On Twitter: @Porter_Anderson

Porter: you have summoned up a pure, unalloyed image to capture Sartre’s aphorism that “hell is other people.”

Porter –

Provocative indeed.

I’m going to pick up BHL’s book. Good marketing – are you available to increase my readership (haha)?

Your questions regarding minimizing or making negotiable in our writing the dangers we face highlighted the opposite for me.

It seems that creative writing tendencies/craft have regularly infiltrate the “factual” reporting that influences and shapes individuals’ perception of the dangers we face.

Viruses are bits of genetic code wrapped in a protein coat. In some respects so limited (can’t replicate unless in a more complex organism’s cell) that some argue they are barely a life form. They, in some respects are like rust or mold—they increase when introduced to conditions that allow them to. They have no thought. They do not scheme. They do not direct the entirely random process of their mutation. Reports anthropomorphize viruses suggesting they consciously direct changes to dodge vaccines, spread more readily, and defeat therapies.

When these infective bundles of chemicals are described as having the diabolical intent and intelligence of Sherlock Holmes’s arch rival Moriarity the “evil” is not minimized or made more negotiable.

The reality is worrisome enough but I’d suggest much of the written treatment of the threat represents the danger as even more grim than the sobering reality.

Putin is an altogether different danger.

In the age of weapons of mass destruction, one can argue that man is man’s greatest threat.

The thing is, Putin does have a backstory. For me, the challenge lies in not accepting it as an excuse for the havoc he wreaks in the world. I think of him (and other destructive figures) as a virus. Only a true virus such as Covid does what it’s supposed to do. In that way, it has a kind purity. But for a human being with the potential to choose differently? In my writer’s mind, that begs exploration. But I have been around narcissists, and from one in particular, I learned to acknowledge the lack of empathy and head for the door.

Porter, your piece is frightening and beautiful. It is truth spread out like a corpse for us to view. My somewhat scientific background (nursing medicine) made me crazy during Covid. No, you can’t see a virus, but they are all around us, this one more virulent, this one needing to be conquered by science like polio. But humans often tend to death not life. It won’t touch me: some unknown desire to not accept reality. Putin is his own virus, rising up from almost nothing, yet having some inner power to convince others to allow him air and water, decision and power. Today, I’ve been thinking about mortality. It feels closer somehow. So I’ll write, call my children, do what I do to keep living. It’s really the only choice we have.

Our world leaders are all evil. If covid didn’t kill you, there was the response to it–lockdowns, experimental gene-therapy (please don’t call them vaccines), and now the threat of a nuclear war. Oh yes, Satan’s having a grand time. He’s the father of lies and we keep falling for them. My response is to retreat into prayer. Only God can save us. Parce Domine.

“Is it that “hopeful” impulse that drives us to want to water down the mindless danger of something, to make it negotiable? Does it work?” Without evil, in the form of someone who believes “Why not me?” to manipulate another human, my story doesn’t exist.

Getting around evil once it is recognized, taming it, negotiating with it, is what we call ‘conflict’ – and the hope comes from seeing how well it does or doesn’t work. Two good people would never team up, never solve the situation together, if evil hadn’t decided it was somehow okay.

I’ve been checking that story for plot holes and impossibilities for over twenty years: the good would never happen if the evil didn’t have to be foiled. To protect the innocent. Implausible, yes; but not impossible.

With respect, if you’re open to revising this essay, please consider removing the reference to George Bernard Shaw. Despite his fine writerly qualities, his zeal for the Soviet Union led him to write articles that denied the Holodomor and effectively laundered Stalin’s reputation in the West. Praise for Shaw in the opening line undercuts subsequent support for Ukraine.

(Did any reader know this before I mentioned it? Maybe not. They do now, though, and the article suffers for it.)

Yes, I did know it. At the end of the nineteenth century, Shaw was an early adherent of Fabian Socialism (a much different thing from Marxist/Leninist communism), but he later followed a much more radical path.

Porter: thanks for your book review and meditation on its message.

The impulse to route ourselves around, over or under what hurts or depresses is a survival mechanism. It helps us push back against despair. But this same mechanism is a two-edged sword. Resorted to as an alternative to clear thinking, it becomes a form of evil itself. People who hide behind high-minded pronouncements about freedom and the Constitution instead seeing the selfish evil at the heart anti-vaccination “reasoning” are illustrations of this. So is anyone (other than a professional propagandist) whose words and deeds apologize for the lies told by a pundit, politician, or tyrant.

I think the pressure to seek a comforting escape when faced with evil–viral or human–has grown much worse, much more dangerous. I think this is due to the unstoppable, unavoidable exploitation of imagery and language in electronic media. What we live with is an endless bombardment that takes its cue from the old newspaper watchword, “If it bleeds, it leads.” If it’s disastrous or extreme in some way, that’s what is front and center before us on our TVs, computers and phones. This relentless assault on consciousness has, at least for me, made it more and more difficult to maintain a sense of balance. Putin is evil. He is the bleeding that leads every day–every day that so many flawed but fundamentally decent leaders and others make an effort to do, in a compromised way, the right thing. But they don’t bleed, so they have little or no voice. As for the young, a great many have little or nothing to do with any of this. Their version of “if it bleeds it leads” are games that distract and absorb with an equivalent escapist function. Or so one old man thinks.

Porter — sorry to be late to the discussion. And since we’re moving and the internet is gone I only have my phone, so I’ll make this brief. Joyce remarked that a work of art should not inspire action but a kind of suspension in awe. Evil can evoke a similar response — dumbstruck terror. It is why the courage to act — rather than succumb to despair, say, or retreat into the sanctimonious self-congratulation of prayer — inspires us so profoundly. Because evil is not the dark side of beauty or the divine. It is sui generis. It is also willful. I would in fact exclude viruses from the pantheon of evil, just as I would wild beasts and violent storms, due to the absence of cruel intent. But evil’s investment in cruelty is exactly its weakness — the point of vulnerability where it can be attacked. For it inspires in its opponents an even greater resolve to unite, resist, fight, to the death if need be. For a a life defined by compromise with cruelty is slavery.

Wish I wasn’t commenting on my phone, but perhaps that is good. Otherwise I could type forever…

I suppose the only thing I can say to this is that for a very long time people have desired to explain evil away (it’s genetics, it’s how he was raised, it’s psychology, it’s a chemical imbalance, it’s violent video games, it’s substance abuse, it’s all relative) because to believe in actual Evil implies a belief in actual Good, which then requires a reckoning with truth claims many people would prefer to ignore so as not to disrupt their comfortable lives.

My worldview accommodates evil and good. So none of this surprises me. But I am challenged to think about my writing. Do I let that belief exist there? Do I take it far enough? Or do I worry an audience might not follow?

Erin, I’m going to address your questions in my next post. Porter’s post here has opened an important topic.

I’m looking forward to reading it! (as always) :)

A “like” / “upvote” didn’t feel like enough. This is THE comment. <3

Love this: “The hope is in how we respond, not in obfuscating the terror.”