Joan Didion: Clarity Trumps Expediency

By Elizabeth Huergo | January 25, 2022 |

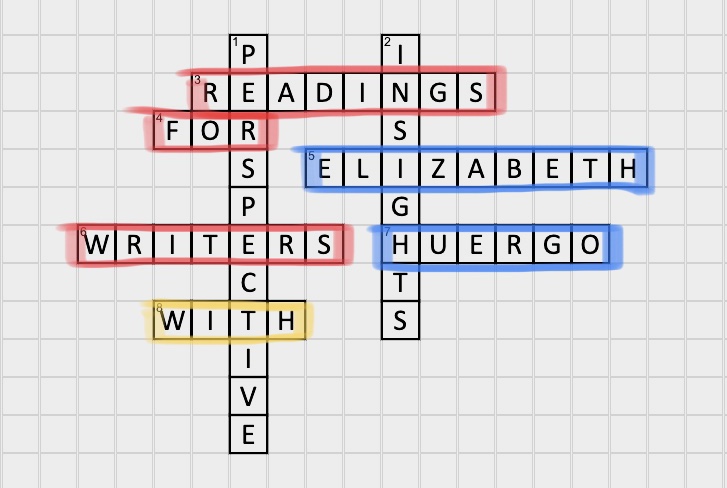

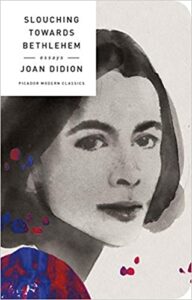

Slouching Towards Bethlehem was the first collection of Joan Didion’s essays that I ever read, attracted by the allusion to W. B. Yeats’ “The Second Coming,” a favorite poet and poem. Didion, born in 1934, died this past December 2021; Yeats, born in 1865, died in 1939. Their lives straddled centuries so that, like Janus, the Roman god of beginnings, they each faced in two directions. Yeats looked to the past (a world war, ancient scholars, the Book of Revelations) to prophesize about the future. Didion focused on the present, honing an uncompromising will to see and name what she saw.

Slouching Towards Bethlehem was the first collection of Joan Didion’s essays that I ever read, attracted by the allusion to W. B. Yeats’ “The Second Coming,” a favorite poet and poem. Didion, born in 1934, died this past December 2021; Yeats, born in 1865, died in 1939. Their lives straddled centuries so that, like Janus, the Roman god of beginnings, they each faced in two directions. Yeats looked to the past (a world war, ancient scholars, the Book of Revelations) to prophesize about the future. Didion focused on the present, honing an uncompromising will to see and name what she saw.

For Didion, the writer must see with a nearly prophetic clarity that strips away sentiment and anything that obstructs, which is perhaps why she ends her preface to Slouching Towards Bethlehem with a warning: “writers are always selling somebody out” (italics original). Clarity trumps expediency every time. Writing is not predicated on a desire for objectivity, which is itself an impossible fantasy, but rather an unwavering intention to observe her heartfelt response to the world. There is nothing ascetic or mechanical to what she describes. As she notes pointedly, “since I am neither a camera eye nor much given to writing pieces that do not interest me, whatever I do write reflects, sometimes gratuitously, how I feel.”

For Didion, the writer must see with a nearly prophetic clarity that strips away sentiment and anything that obstructs, which is perhaps why she ends her preface to Slouching Towards Bethlehem with a warning: “writers are always selling somebody out” (italics original). Clarity trumps expediency every time. Writing is not predicated on a desire for objectivity, which is itself an impossible fantasy, but rather an unwavering intention to observe her heartfelt response to the world. There is nothing ascetic or mechanical to what she describes. As she notes pointedly, “since I am neither a camera eye nor much given to writing pieces that do not interest me, whatever I do write reflects, sometimes gratuitously, how I feel.”

Yeats developed his fantastic ideas about history and aesthetic production over many years and most fully in A Vision (rev. 1937), a fascinating collection of stories, theories, reflections, and metaphors that serve as a key to his poetry, his sense of humor, and his grappling with modernity. Yeats imagines human history in two-thousand-year cycles, and he represents these cycles as cones. Time spirals from the apex to the base of the cone and back. At the apex, the narrowest point in the cone, the centrifugal forces, the social and cultural values that hold us together, are the very strongest and produce great art and human advancement. As the point farthest from the apex, the “widening gyre” or base of the historical cone, we are in “Discord,” in want of harmony, separated from our heart (dis = “apart” and cordis = “heart”).

Didion’s allusion to Yeats’ poem is critical to understanding her despair after the collection’s title essay “Slouching Toward Bethlehem” was published. Didion explains how, for some years, the images in “The Second Coming” had “reverberated in [her] inner ear as if they were surgically implanted there.” The connection between eye and ear is also something Didion shares with Yeats, so the affinity she finds in his lines is no surprise.

In the first stanza of “The Second Coming,” Yeats evokes the approaching moment of collapse: “Turning and turning in the widening gyre / The falcon cannot hear the falconer; / Things fall apart; the center cannot hold.” He situates us at a moment in history when “[t]he best lack all conviction, while the worst / Are full of passionate intensity.” In the second stanza, a vision of Spiritus Mundi, the Spirit of the World, of human history, appears to him. Discord is sure to come, for what he sees at the beginning of the twentieth century, the next two-thousand-year cycle, is a “rough beast,” the Anti-Christ, “slouching towards Bethlehem.”

I like to think great poets write history better than great historians, if only because poets are willing to leap from anecdote to inference, to extrapolate from observed feeling a prophetic insight into the world they witness. “The Second Coming” was published in 1920, after the First World War (1914-1918). Both anarchy and “the blood-dimmed tide” had been set loose across Europe, and the next tide, the Second World War (1939-1945), was still looming in the distance like one of Goya’s giants.

I like to think great poets write history better than great historians, if only because poets are willing to leap from anecdote to inference, to extrapolate from observed feeling a prophetic insight into the world they witness. “The Second Coming” was published in 1920, after the First World War (1914-1918). Both anarchy and “the blood-dimmed tide” had been set loose across Europe, and the next tide, the Second World War (1939-1945), was still looming in the distance like one of Goya’s giants.

Yeats’ vision is apocalyptic. Didion’s is not, perhaps because, as an adult, two world wars and Hiroshima were already behind her. That said, her observations of American culture in the second half of the twentieth century and the beginning of the twenty-first, are often morally fraught. “Slouching Towards Bethlehem” develops from her experience of the Haight-Ashbury district of San Francisco in the spring of 1967, an experience that magnified those reverberations of Yeats’ poem in her inner ear. As she explains:

It was the first time I had dealt directly and flatly with the evidence of atomization, the proof that things fall apart: I went to San Francisco because I had not been able to work in some months, had been paralyzed by the conviction that writing was an irrelevant act, that the world as I understood it no longer existed. If I was to work again at all, it would be necessary for me to come to terms with disorder. That was why the piece was important to me.

Yet, after its publication, she felt she had failed. Her audience was focused on details–the fads, inconveniences, and outright dangers of what was happening in Haight-Ashbury. She, on the other hand, was writing about what was not there, what lay on the horizon, a vacuity at the heart of a culture, and what that absence promised if we failed to see it as a prologue of the discord looming in the future.

She did not set out to write a jeremiad or to develop an extended metaphor, but to write what she saw and felt because “[o]nce we had seen these children, we could no longer overlook the vacuum, no longer pretend that the society’s atomization could be reversed.” Her use of the word “children” provides insight into how she approached the task. What Didion saw in Haight-Ashbury were not young people or young adults, which is how the news media often represented them. What she saw were children ages fourteen and fifteen, sixteen and seventeen attempting to “create a community in a social vacuum.” What she saw was a political movement that the news media could not see because they were more interested in observing each other.

Written in the first-person, the essay has a picaresque quality–episodic and, at points, consciously repetitive. It is as atomized as the world she is observing until she reaches those moments when the weight of her vision distills into a conclusion; for example, that what she was seeing was more than the rebellion of the young against the old:

At some point between 1945 and 1967 we had somehow neglected to tell these children the rules of the game we happened to be playing. Maybe we had stopped believing in the rules ourselves, maybe we were having a failure of nerve about the game. Maybe there were too few people around to do the telling.

For Yeats, a modern poet, language still held the promise of community and transformation. For Didion, a post-modern writer, the promise had been broken. Between the end of the Second World War and 1967, a certain story about the practices of US society had stopped being told and language become dead metaphor, euphemism. Nevertheless, she remained “committed to the idea that the ability to think for one’s self depends upon one’s mastery of the language.”

She is “not optimistic about children who will settle for saying that their mother and father do not live together, that they come from ‘a broken home’.” The home was not broken. Something happened to the people who inhabited that home. What exactly? Euphemism obscures the problem and so makes the possibility of working toward a solution less likely. The children Didion saw in Haight-Ashbury were “less in rebellion against the society than ignorant of it, able only to feed back certain of its most publicized self-doubts, Vietnam, Saran-Wrap, diet pills, the Bomb” (italics original). These children can only “feed back” platitudes. They do not trust words.

Hers is the exact opposite of political language, as Orwell described it in “Politics and the English Language.” Of course, we have paid little attention to either Didion or Orwell, and we witness the resulting failures every day now; for example, when a surgical mask is falsely equated with the suppression of free speech; when insurgents are referred to as “tourists”; when a free and fair election is called a “coup”; when pundits tell us with a straight face that the US has always respected the sovereignty of other nations. We have become even more atomized and even more euphemistic than Didion feared. We have become comfortable with looking away and finding the news outlet that most conforms to our established prejudices. As writers, though, we have an obligation to clarity of vision, to locating those reverberations between world and heart, even at the risk of “selling somebody out.”

Do you have a favorite work by Yeats or Didion that especially resonates with you? What are you working to observe in our world? Do those observations have a place in your writing?

[coffee]

Thank you for your thoughtful essay. For me, a compelling and recurring observation of the world is how dangerous it is to take something generally unexamined for granted: that the earth’s resources exist strictly for human exploitation; that the cultural status quo is moral; that power and wealth bestow authority; that progress is inevitable. In my current writing project, working title The Relic, I’m exploring the ramifications of how a relic that everyone knows is fake bestows magical powers to a disgraced gay monk.

Thank you for your observation, Lloyd. It is a dangerous and high-stakes game to leave assumptions unexamined and to behave as if those assumptions are not framed by interests. I appreciate you taking the time to post. Cheers, Liz

Elizabeth,

what a brilliant and bracing start to the morning. I feel as if every sentence I have ever written is suddenly sitting up and taking stock of itself. This discussion of Didion and Yeats serves as a sharp reminder of my role as an author… to not bandy about words and stories as if they have little impact on culture. Thanks for the wakeup call.

Thank you for being such a generous reader, Tom. I appreciate your response. Cheers, Liz

I came late to reading Didion. And of course, I read Yeats in college, his words like flames that never burn out. The Year of Magical Thinking was the first of hers that I read, and then Blue Nights. Her taut language dealing with deep grief was stunning. I read more after that, listened to her books on tape. I was living in California at the time. I lived what she wrote about the Santa Anna winds. Didion explored this country, allowed her keen observations to strip us down to realities. She will be sorely missed, as we need her now, her observations, cutting and true. Thanks for this post.

Interesting. I don’t have a favorite Didion or Yeats piece. Perhaps Didion’s descriptions of Haight-Ashbury cut too deep but were par for the course when I was a teenager in the years that followed her observations. The aftermath of all that “peace and love” did, after all, evolve into the ’80s, as Yeats’ observations evolved in the aftermath that was Didion’s presence. Thank you for this post. You’ve convinced me that I need to go back and reread their stuff.

PS I know that T.S .Eliot spoke to me as a teenager and now. The Hollow Men is as prophetic today as it was when first written, and I suspect that if Eliot had lived in Ancient Egypt, it would have rung just as accurate an observation as it is now.

Thank you, Bernadette. I agree that Didion’s observations about Haight-Ashbury cut deep. There is a shocking moment when she is describing a five-year-old child on acid, the drug given to her by her young mother, who seems to do this on a regular basis. Didion’s language, her sentences are stripped down, and you can feel her presence in the scene she is observing. My favorite essay in the collection is actually ‘Some Dreamers of the Golden Dream,” in which the landscape is a character in a story that rivals the horror of Chaucer’s “The Pardoner’s Tale.” Yes, Eliot is prophetic. Cheers and thanks, Liz

My favorite Yeats lines are from The Lake Isle of Innisfree: “Nine bean rows will I have….And I shall have some peace there….” This cracks me up every time.

Obviously Yeats never grew beans, or he would not have expected to have peace when those nine rows of beans came to maturity all at once.

If this is not brief enough, please let me know.)

Anna, I think Yeats would appreciate your response. His sense of humor is evident at so many points in his work. Thank you for taking the time to respond. Liz

Well done. Thank you. I love, especially, your exhortation at the end to us to write with clarity. Didion and Yeats would approve, I think.