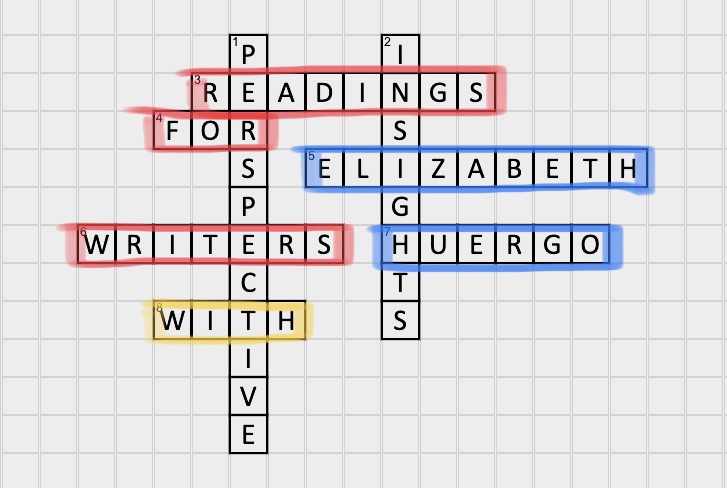

Readings for Writers: Genre and Its Discontents

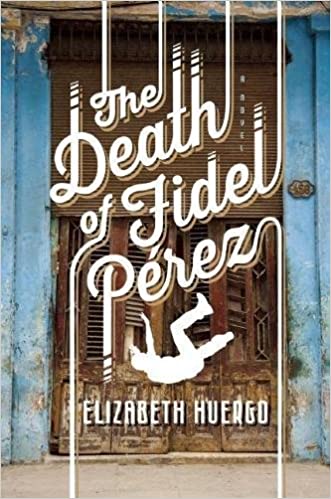

By Elizabeth Huergo | October 26, 2021 |

All writing is a form of storytelling, so if you are puritanical about genre, this is the point where you should clutch your pearls and look away. The stark grocery list stuck to the refrigerator door is the skeleton outline of its author’s desire. It promises a plot (a trip to the store); characters (the list maker, the hero who treks to the store, store clerks and cashiers and inattentive customers); conflict (what if there are no vine-ripe, organic, locally sourced heirloom tomatoes?); setting (pristine kitchen, packed parking lot, labyrinthine rows of cans and jars); and any number of themes and symbols (the Siren song of the cookie aisle, empty shelves, and banks of crisp, glistening greens). Can you understand now how the desire for that perfect Tinga de Pollo lies tacit in the stark outline scribbled on a scrap of paper and stuck with a magnet to the refrigerator door?

All writing is a form of storytelling, so if you are puritanical about genre, this is the point where you should clutch your pearls and look away. The stark grocery list stuck to the refrigerator door is the skeleton outline of its author’s desire. It promises a plot (a trip to the store); characters (the list maker, the hero who treks to the store, store clerks and cashiers and inattentive customers); conflict (what if there are no vine-ripe, organic, locally sourced heirloom tomatoes?); setting (pristine kitchen, packed parking lot, labyrinthine rows of cans and jars); and any number of themes and symbols (the Siren song of the cookie aisle, empty shelves, and banks of crisp, glistening greens). Can you understand now how the desire for that perfect Tinga de Pollo lies tacit in the stark outline scribbled on a scrap of paper and stuck with a magnet to the refrigerator door?

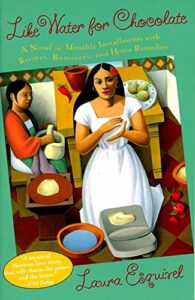

Organize the list, add to it a series of imperatives (chop, toss, stir, drizzle), and it becomes a recipe, another tacit story about a cook and what and whom she loves. Insert the recipe, along with a few other favorites, into a story of two young, star-crossed lovers, and it becomes the novel, Like Water for Chocolate, the recipes reinforcing aspects of Laura Esquivel’s story: the role of women in a patriarchal family, the expression of love (familial and erotic) through cooking. Squint and the novel becomes part sociological treatise (a story about Mexican society at the end of the nineteenth century). Squint again and it is a historical narrative (a story about the Mexican Revolution). Esquivel’s novel is a fable, an epic, another example of magical realism, the critics sputtered. They want desperately to classify it, which is a little like killing something in order to possess it.

Organize the list, add to it a series of imperatives (chop, toss, stir, drizzle), and it becomes a recipe, another tacit story about a cook and what and whom she loves. Insert the recipe, along with a few other favorites, into a story of two young, star-crossed lovers, and it becomes the novel, Like Water for Chocolate, the recipes reinforcing aspects of Laura Esquivel’s story: the role of women in a patriarchal family, the expression of love (familial and erotic) through cooking. Squint and the novel becomes part sociological treatise (a story about Mexican society at the end of the nineteenth century). Squint again and it is a historical narrative (a story about the Mexican Revolution). Esquivel’s novel is a fable, an epic, another example of magical realism, the critics sputtered. They want desperately to classify it, which is a little like killing something in order to possess it.

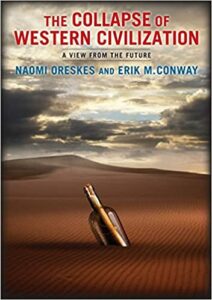

Historians are novelists who feel a near religious devotion to the factual elements of the stories they tell, confessing their slightest detour into the realm of inference as if they committed a deadly sin. Naomi Oreskes and Erick Conway are both historians of science, yet the confounding problem of how to communicate the rapidly accelerating pace of climate change turns them into iconoclasts.

Historians are novelists who feel a near religious devotion to the factual elements of the stories they tell, confessing their slightest detour into the realm of inference as if they committed a deadly sin. Naomi Oreskes and Erick Conway are both historians of science, yet the confounding problem of how to communicate the rapidly accelerating pace of climate change turns them into iconoclasts.

Genres are useful as long as you are willing to shatter the icons you worship. Consider Oreskes and Conway’s opening sentence, its clauses perfectly balanced, encapsulating the full arc of their story in a manner reminiscent of Dickens: “Science fiction writers construct an imaginary future; historians attempt to reconstruct the past.”

One sort of writer looks forward and the other back; one puts things together, the other takes things apart; and both want to understand the present moment.

Oreskes and Conway imagine how a “future historian” writing in the year 2393 from somewhere in the Second People’s Republic of China might struggle to understand how a civilization as brilliant as the West could also be so bloody stupid, how “[k]knowledge did not translate into power.” The plot of the “future historian’s” story is our collapse. The story, however, “essays” (tests, tries) itself, offering factual answers extrapolated from scientific data.

What does the “future historian” conclude about us?

We value money more than human life, more than plant and animal life. We have allowed a small, self-interested minority to hold all the political power. We have nurtured hyper-specialization instead of broad, general knowledge, thus impeding the flow of important scientific information across civil society.

We tell stories of every sort–for ourselves and because we want others to see what we see. As readers, we recognize another writer’s struggle to organize, share, and possibly ameliorate some aspect of what ails us all, the violence in this world, the suffering we impose on one another. Reading is as close as any of us can get to entering another person’s consciousness and seeing how they see. My favorite writers turn the world upside down, shatter genres, and demand that I look again, for their sake and for mine.

How does genre help or hinder you as a writer? What have you read recently that challenges your sense of what a particular genre should be?

[coffee]

“They want desperately to classify it, which is a little like killing something in order to possess it.”

This is the sentence that is going to stay with me, though you’ve left me — as always — with much to think about, Elizabeth. Thank you for today’s essay!

You know a paragraph that begins with “We value money more than human life…” is true when it elicits silence. I very much enjoyed this post, Elizabeth. I write otherworld fantasy because it allows me to address sensitive topics in a setting that makes them less immediately threatening. It also allows those lacking a voice to find one.

Genres are helpful because of the expectations they create. I write for kids and no matter how dark a story goes, it always, always ends with hope. I cannot imagine a world without it. Thanks for this essay, Elizabeth, because I’ve been looking back with my historical but it also makes me look forward because at times I think we’ve learned nothing at all.

The grocery list that could read like the plot of a story. The weather that knocked out my son’s electricity so that he had to come to our house to stay warm to work. We live story every day. Can it be classified? Can it be forced into a mold? Many writers abhor categories because they lead to marketing. Writing is creation. We should not have to think about marketing while we are creating. Sigh.

I love that you started this with grocery lists. I’ve always seen stories in them. I have some from my great aunt, from a hundred years ago. Others from my mom, some of my own. It’s amazing what a difference as little as a decade makes to the grocery list story. It may have been written as joy of a new marriage, yet 100 years later seen as the waste of an intelligent mind. It may have been written as a goal to support the health of the family but eventually seen as the poison that caused heart attacks and strokes.

My point is most of what is written in the past changes. The words stay the same but the reader changes, because the reader is always in the present, a product of their time. The lobby of my nearby library offers free old books. It’s fascinating how most everything is dated and colored by the time it was written. Sometimes it’s quaint and funny, but more often it’s disturbing.

It all makes me feel the only thing certain about what is written today is that it will read differently tomorrow.

I do feel constraints in writing a novel in the form that’s expected. There’s lots more I could say about that, but better to work on my WIP today and try to create an example of a genre buster.

Thanks for the fuel, today.

Great observation, Ada. You could write a whole post on that subject alone.

“We value money more than human life, more than plant and animal life. We have allowed a small, self-interested minority to hold all the political power.”

While so incredibly true, that made me so incredibly sad. I am close to giving up hope that anything in those two powerful sentences is going to change, which is why I turn more and more to books and stories.

Right now I’m reading an ARC of The Way We Weren’t by Phoebe Fox. It’s a woman’s novel that doesn’t hold strictly to the conventions of romance, and I like that about it. I’m almost finished reading and still being surprised. When a book does that to me, I forget about the world problems for a little while.

Off the track but not: A wonderful story involving history (in the future) being shaped according to a misunderstood grocery list from the past is “A Canticle for Leibowitz,” written by Walter Miler in 1959. Once again, this novel defies category.

(Michael Johnson, master typist)