To Whom It May Concern

By Dave King | May 18, 2021 |

Flickr Creative Commons: Liz West

If you were newly rich or socially ambitious in the 18th century and wanted to fit in with the quality, there were plenty of people willing to teach you the skills you needed. Elocution schools would help you lose the gutter accent. Deportment classes would keep you from embarrassing yourself with your table manners. And manuals of model letters would show you how to express yourself in writing with appropriate dignity and grace.

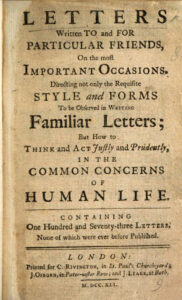

The most popular of these was the 1741 Letters Written to and for Particular Friends by Samuel Richardson, who later went on to help invent the novel with Pamela. Richardson included model letters for all sorts of extremely specific situations, including, “To a Daughter in a Country Town who encourages the Address of a Subaltern (a Case too frequent in Country Places),” and “A young Woman in Town to her Sister in the Country, recounting her narrow Escape from a Snare laid for her on her first Arrival by a wicked Procuress.”

In an age when we are never out of reach of a phone, which also allows us to instant message, Facetime, and post pictures of our pets for the world to enjoy, it’s hard to imagine the role that letter writing used to play in people’s lives. In late 19th-century London, mail was delivered twelve times a day, allowing correspondents to practically carry on a conversation by letter. Nearly all contact with family members and friends who didn’t live within walking distance took place through the mail. If you wanted to buy something that wasn’t available in the local shops, you sent letters to more distant sellers. If you could read and write, you owned paper, pens, and an inkwell. Until the middle of the 19th century, when steel pen nibs were invented, you also owned a penknife to sharpen the specially cut feathers that did the job. (Ruth once made a pen from a discarded turkey feather. It’s easier than you might imagine.)

In an age when we are never out of reach of a phone, which also allows us to instant message, Facetime, and post pictures of our pets for the world to enjoy, it’s hard to imagine the role that letter writing used to play in people’s lives. In late 19th-century London, mail was delivered twelve times a day, allowing correspondents to practically carry on a conversation by letter. Nearly all contact with family members and friends who didn’t live within walking distance took place through the mail. If you wanted to buy something that wasn’t available in the local shops, you sent letters to more distant sellers. If you could read and write, you owned paper, pens, and an inkwell. Until the middle of the 19th century, when steel pen nibs were invented, you also owned a penknife to sharpen the specially cut feathers that did the job. (Ruth once made a pen from a discarded turkey feather. It’s easier than you might imagine.)

It’s hard to flip through a book written before the telephone (and many afterwards) without finding several letters quoted at length. Entire novels were constructed solely from letters, from Samuel Richardson’s Pamela through The Color Purple. But letters weren’t just pervasive in literature because they were such a big part of life. Quoted letters give storytellers a unique opportunity to accomplish things they can’t do with simple dialogue.

A letter is essentially a natural uninterrupted monologue, giving your correspondent a chance to pile on their view of things without contradiction. In Pride and Prejudice, when Lydia sends a letter to her friend Harriet saying she’s eloped with Wickham, readers get a full page of nonstop frivolity that emphasizes just how much trouble Lydia is in. “. . . it will make the surprise the greater, when I write to them, and sign my name Lydia Wickham. What a good joke it will be!”

Letters also give readers a window into how characters see themselves. As Richardson’s model letters show, even when letter writing was common, correspondents put thought and care into what they wrote. The style of their prose, as much as their choice of clothes or grooming, showed the face they wanted to present to the world. That gives storytellers a chance to contrast how letter writers see themselves with how the rest of the world sees them. When the unctuous Mr. Collins sends his condolence letter to the Bennets over Lydia’s elopement, the letter shows just how unconscious he is of the massive self-righteousness woven into his sympathy. “. . . this licentiousness of behaviour in your daughter, has proceeded from a faulty degree of indulgence, though, at the same time, for the consolation of yourself and Mrs. Bennet, I am inclined to think that her own disposition must be naturally bad, or she could not be guilty of such an enormity, at so early an age.”

So, if you’re writing historical novels – and that would include anything up until a few decades ago – don’t forget the role letters played in your characters’ lives. Or the role they can play in your fiction.

Even if you’re not writing historic fiction, modern forms of communication over a distance offer a lot of the same advantages as traditional letters. A tweet won’t show the same care and consideration as a handwritten missive, but it is still self-conscious enough to show how your characters think of themselves. Twitter and Facebook have endless hours of fun with people who aren’t aware of what their tweets and posts reveal about themselves.

If you need to track some bit of action that takes place over time but isn’t critical enough to build into a series of scenes, consider a string of tweets or texts or posts. They are much more personalized than a paragraph or two of narrative summary, give you a chance to reveal your characters’ take on things, and are often much easier to read.

And if you’re interested in social satire, well, modern social media provide a target-rich environment.

P. G. Wodehouse had a lot of fun with the instant communication of his day – the telegram. Since you paid for wires by the word, they gave rise to a system of abbreviation as elaborate and stylized as anything on social media today. “I got the message you sent on the 15th. I’ll be there as soon as I can,” would boil down to “Yours 15th received. Arriving soonest.” Or, as Bertie Wooster once cabled to Gussie Fink-Nottle, after learning that Gussie had broken off his engagement to Angela Bassett, “You say ‘come here immediately,’ but how dickens can I? Relations between Pop Bassett and self not such as to make him welcome Bertram. Would hurl out on ear and set dogs on. What serious rift? Why serious rift? Why dickens?”

I’m sure there’s an equal amount of fun to be found with emojis and hashtags.

I’m sure I haven’t exhausted the topic. How have you seen letters used in literature? Have you used tweets, hashtags, and emojis in your own writing? They often play a role in modern television, I’ve noticed. (Looking at you, Emily in Paris.)

[coffee]

Oh I love this, Dave. I have used letters in my historical fiction. And the research is often fascinating. When I read the old letters of authors, I get a much clearer sense of the person, the emotions, and style of living. I read the letters of Virginia Woolf. Wow, is all I can say. Great post today.

That actually is another aspect of a letter — how they reveal relationships. Most of the time, when you write to someone, they are the sole focus of your attention. A letter reveals, possibly more than an ephemeral dialogue, how you feel about them.

Yes, informative, Dave! I have never seen the power/meaning of letters to past generations so well-defined as you have here, even though sure, I got it that communication options were limited. Thanks.

As I say, if something is such a deeply integrated part of everyday life that people stop noticing it, then it’s easy to forget once it’s gone. For instance, I suspect encyclopedias, which used to occupy pride of place in any well-educated home, are now largely forgotten.

I love epistolary novels so much — GRIFFIN AND SABINE was one of my favorites, but I also loved LADY SUSAN too. Thanks for sharing this!

I’d put in my vote for Where’d you Go, Bernadette, as well. And in The Lost World, Arthur Conan Doyle managed to construct an adventure built from dispatches from the field written by a journalist. All the more remarkable since the novel first appeared as a serialized story in The Strand.

And don’t forget my fave, Dracula. It’s been a long time, but I remember it as mostly letters and reports.

Wonderful post, Dave. I relish letters in novels, especially historical fiction. I decided to relate a section of my upcoming release (Shiloh, Oct 5) largely with letters. Aside from using them in my novels, I’ve also used letters as a tool to capture a stubborn character’s voice and perspective on a story issue (especially non POV characters who have a stake in things). I’ve let them pour out their woes on paper with themselves firmly situated as the protagonist in the situation. It helps paint an antagonist as someone with a legit side of an argument or issue (in their own minds at the very least). That sort of letter is just for me, the author.

I like the exercise of having your characters write a letter. As I say, letter writing encourages self-awareness and focus on your recipient. It is a good way for characters to find themselves.

I have used Tweets and emails in my writing. In my latest WIP the protagonist is a reporter and I’ve thought about including the article he wrote rather than just mention the title or topic in the narrative. Not sure about this yet.

Bob, I can see a lot of considerations that would go into that decision. An article — and a letter, for that matter — do interrupt the present action. The question is, is what readers gain from the article or letter worth stopping the immediate story for?

With an article, there’s also the question of how much it would reveal the author’s character. Journalists are a bit more constrained than letter writers — by their journals’ stylistic conventions, by the need to reach a wider audience. I would think that, other things being equal, an article would be harder to quote than a personal letter.

On the other hand, I just mentioned Conan Doyle’s The Lost World, built entirely from a journalist’s dispatches.

Dear Dave,

I love this post and always enjoy novels where communication is often done through letters. In Tayari Jones novel, An American Marriage, letters are used to not only flesh out the story, but to provide communication between the main characters, because the husband has been falsely accused and is serving out a jail sentence. We would not know some basics of their relationship, the beginnings of the marriage, were it not for the letters and how the two are dealing with this traumatic separation. GREAT POST. Sincerely, Beth Havey

Well, hey, I’m old enough to have relied for many years on letters as the basic form of communication. Long letters, meaty letters, letters written regularly, incoming letters awaited with much anticipation, letters saved in empty stationery boxes (remember them? perfect size for their next use), polite thank-you letters written by children as a discipline to be learned for life—the Christmas thank-you must be written with a fountain pen and postmarked before New Year’s Day. And letters deliberately omitting the bits of information craved by the recipient.

Getting around to our immediate concerns: much of my narrative nonfiction WIP depends on a huge cache of handwritten letters, treasured and saved, passed around through the family before circling back to their addressees. Later, when typing often replaced handwriting, the letters are just as heavily laden with information, opinions, and expressions of affection.

Looks like I’m lucky.

I was there, too. I had my first pen pal when I was twelve — another disappearing tradition — and wrote personal letters through college and beyond. I still have a drawer full of personal letters that will probably mystify and amuse my heirs and assignees in years to come.

My Dear Sir,

We must Zoom soon, there is much to relate and discuss and the pleasure therein shall be considerable. However, I fear that the scheduling of such Zoom meeting will be a protracted undertaking, with much e-mailing back and forth and working around our busy schedules, not to mention the unfortunate separation of our time zones.

Telephoning likely shall also prove difficult to arrange. I would suggest Twitter or Facebook as a medium of communication but that is like whispering in church. Everyone is listening and will of course have something to say regarding the matters of our discourse.

Thus, I think the better solution is the post. I am afraid that my typewriter has been lacking a ribbon for some time, our goose has died and the India Ink in my inkwell is dried up. What are we to do? Why, find a goose, I should think, and I am told that blood serves as well in the quill.

There! We are set. I shall scribble to you shortly; this is, as soon as I locate a goose and persuade it to surrender a feather. Oh wait, where is my penknife? And have I saved two pennies for the postage? No matter. I shall borrow a knife from the butcher and pinch coins from a neighbor. Easily done!

Yours most sincerely, etc., etc.,

“From a Friend, endeavoring to arrange a Zoom Call” is one situation Richardson overlooked.

That was delightful, Don, thank you.

Hello, Dave. I so appreciate your post today. I have a novel, written, with two exceptions, entirely in letters exchanged between a soldier in the Civil War and his beloved, suffering her own crises at home. I shelved it years ago because I was told too many times that the format is passe and nobody would be interested.

I knew intuitively that it WASN’T wrong, but couldn’t defend it intelligently, so there you go. You have given me hope. I may drag it off the shelf as it turns out that it might be a companion piece to my work in progress. So, thanks so much.

BTW, this is the first post I’ve ever commented on. That’s how much I appreciate your thoughts.

Jan, go for it. I would gladly read that novel.

Wow, I’m honored, thanks.

I’m not sure any storytelling form ever becomes passé, as long as it fits the needs of the story. The most recent epistolary novel I’m aware of is Where did you go, Bernadette, and it felt entirely up to date.

Dave, what a lovely post. I actually grew up writing and receiving letters because ours was a fractured family. Later, my boyfriend (later husband) and I wrote letters to one another because we were each involved in our work. Strangely, the habit continued even after we no longer had the need because it was a way to gain clarity about things and situations. It’s only last year, when he started working from home that the letters stopped.

I use letters in my historical fiction but also to discover what my characters think and feel. How they write to other characters reveals so much about them and it gives me access to their voice.

And in my contemp. fiction, I do use the newfangled technology. It doesn’t play a major role though, probably because I don’t care for it.

Btw, CS Lewis’ collection of letters and Flannery O’Connor’s are two gems I keep handy.

Ruth and I met when I was giving a workshop at an Episcopal monastery in upstate New York in December. We then wrote letters back and forth for months and only met again in person in July. We were married the following October. That was twenty-nine years ago.

Perhaps that’s why letters are so important to us. Which may be why she suggested this topic.

We’re glad she did, but what was she doing in a monastery?

She was attending the workshop, Writing to Inspire. Holy Cross Monastery, on the Hudson just north of Newburgh, NY, acts as a guest house and venue for events like that. Our first real conversation took place in the crypt, surrounded by the remains of dead monks.

Its what rom coms call “meeting cute.”

Aha! What a lovely story, Dave! My husband and I both wish we’d not waited 10 years to marry because it’s been a wonderful 27 years. But those letters are important to us.

I used letters in both the historical subplot of my latest novel and in a historical novella that’s part of a short story collection coming out soon. I really enjoyed the format, even though they are only a small part of each story. In the novella, for example, showing the character sitting down to write her weekly letters to her mother and sister and receiving their replies helped me show the rhythm of her day as well as convey information; this was her time to pause and reflect, and to seek advice, since she was a new bride new in town and had no one to consult with close by. And writing the letters, in both projects, helped me get into the time and place.

Thanks for calling out this lovely tool.

Another good use of letters in a fiction context. I knew I hadn’t exhausted the topic.

I wrote letters the year my husband and I were courting (in separate cities). Some things are better said in ink than email.

I remember feeling distinctly cheesed off when I realized that Jane Austen was getting replies to her letters delivered faster than I was, two hundred years later!

On the subject of letters, I recently read My Hand Will Write What My Heart Dictates, a collection of letters, diary entries etc from women living in New Zealand in the 1800s. Well worth a read!

And yet somehow I don’t think I’ve ever used a letter in a book. Something to think about, certainly!

Letters are remarkable historic documents, and if you’re writing historic fiction, they give you an insight into how ordinary (educated) people used language at various times in the past.

One of my favorite examples is from local history — all the documents are now in the Ashfield Historical Society. In the 1850’s, according to the journal of Ebenezer Graves, a 20 -year-old member of a farming family, his cousin Darwin disappeared. They later found Darwin’s trunk in an inn in Vermont and, though Eb doesn’t say why, assumed he’d committed suicide.

Two years later, Eb’s family received a letter from Darwin, from Honolulu. He had gone to Boston and joined the crew of a whaler.

The letter is remarkable both for what it says — it’s one of the few descriptions of what life on a whaler was like for ordinary crewmen — and what it leaves out. Darwin was apologetic for abandoning his family and promised to come back some day. But he never mentions why he left. And, incidentally, he never did make it back to Ashfield.

Re: Letters in historical fiction. I must chime in and mention the wonderful historical, romance, coming-of-age novel THE SHADOW OF THE WIND by Carlos Ruiz Zafón, in which a letter is a key element of the plot.

Thanks, Marcie.