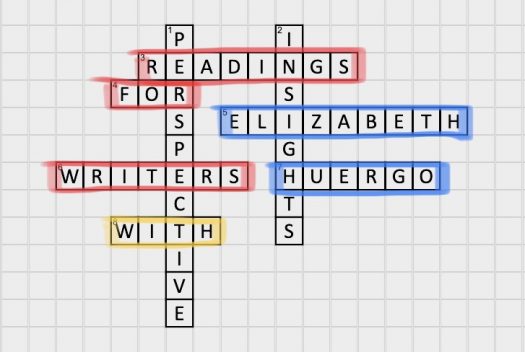

Readings For Writers: Kathleen Alcalá and the Extraordinary

By Elizabeth Huergo | April 27, 2021 |

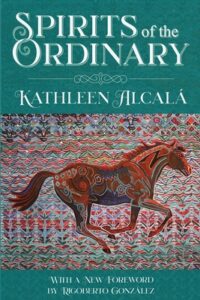

Kathleen Alcalá’s work often reads like poetry, the sort that draws our attention to the distance between what we think we have seen and what is actually there. Alcalá’s first novel, Spirits of the Ordinary: A Tale of Casas Grandes, originally published in 1996, is being reissued and will be available in May 2021. As a Latina and a writer, I find both solace and inspiration in Alcalá’s work. At every point, she challenges the amnesia that drives the homogenized, often jingoistic narrative about what used to be northern Mexico before President Polk annexed Texas in 1845; and before the treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848 conceded California, New Mexico, Arizona, and parts of present-day Utah, Nevada, and Colorado to the US. The Gold Rush begins in 1848, which is a story often untethered from the bloody battles that barely preceded it. There was a gold rush. The West was born. No need to ask about labor pains.

Kathleen Alcalá’s work often reads like poetry, the sort that draws our attention to the distance between what we think we have seen and what is actually there. Alcalá’s first novel, Spirits of the Ordinary: A Tale of Casas Grandes, originally published in 1996, is being reissued and will be available in May 2021. As a Latina and a writer, I find both solace and inspiration in Alcalá’s work. At every point, she challenges the amnesia that drives the homogenized, often jingoistic narrative about what used to be northern Mexico before President Polk annexed Texas in 1845; and before the treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848 conceded California, New Mexico, Arizona, and parts of present-day Utah, Nevada, and Colorado to the US. The Gold Rush begins in 1848, which is a story often untethered from the bloody battles that barely preceded it. There was a gold rush. The West was born. No need to ask about labor pains.

Alcalá, born in California to parents who immigrated from Mexico, belongs to the southwestern US and to northern Mexico. Reach back further in time and she belongs to the indigenous Opata and to Spain. She belongs as well to two religious traditions, Jewish and Christian, for so many of the Spaniards who immigrated to Mexico were Jews fleeing from the brutality of the Inquisition, people who had learned out of necessity to practice their faith in silence, through the rituals of Catholicism and despite them. Alcalá places her characters in this chaotic crush of cultures, languages, and human desire. Yet she brings us back to the ground of those intersections: everything changes except the fact that everything changes. We come to understand the solace to be found in that acknowledgement.

What do we hold in common despite our differences? The full arc of Alcalá’s novel provides the answer, beginning with the epigraph from The Zohar: “In love is found the secret of divine unity. / It is love that unites the higher / and the lower stages of existence, / that raises the lower to the level of the higher — / where all become fused into one.” The novel ends with a double coda of sorts, an epilogue by the character Gabriel, an Evangelical preacher, the eldest son of Zacharías and Estela; and a promise from the prophet Isaiah that despite the darkness that will cover the earth and its people, “the Lord will rise upon you, / and his glory will appear upon you. / And nations will come to your light, / And kings to the brightness of your rising” (60: 1-3). Three of the world’s major religions claim Isaiah–Christianity, Judaism, and Islam. In a novel about how one thing becomes another, how one tradition can be made to hide safely within another, Isaiah reminds us how mysterious life is, and how easily we are duped by the material world and its mirages.

What do we hold in common despite our differences? The full arc of Alcalá’s novel provides the answer, beginning with the epigraph from The Zohar: “In love is found the secret of divine unity. / It is love that unites the higher / and the lower stages of existence, / that raises the lower to the level of the higher — / where all become fused into one.” The novel ends with a double coda of sorts, an epilogue by the character Gabriel, an Evangelical preacher, the eldest son of Zacharías and Estela; and a promise from the prophet Isaiah that despite the darkness that will cover the earth and its people, “the Lord will rise upon you, / and his glory will appear upon you. / And nations will come to your light, / And kings to the brightness of your rising” (60: 1-3). Three of the world’s major religions claim Isaiah–Christianity, Judaism, and Islam. In a novel about how one thing becomes another, how one tradition can be made to hide safely within another, Isaiah reminds us how mysterious life is, and how easily we are duped by the material world and its mirages.

At the center of the novel are Mariana and Julio, Gabriel’s paternal grandparents. As a child, Mariana was bullied by other children. “Hey Christ-killer,” they jeer at her. “See what it feels like to suffer like our Lord Jesus!” They throw rocks that strike Mariana, leaving her unconscious. Then on the ninth day, “she reached out past [her father], opened her eyes, and said ‘Ángeles’.” Mariana could see the angels surrounding her bed. This mystical experience changed her. She became a dreamer, beatific in her “golden repose,” but she never spoke again. Language becomes extraneous after Mariana sees the angels somewhere in that intersection between conscious and unconscious states. There is no need to explain or express.

Years later, at the age of 24, she married Julio, a man for whom there was only the language of analytical enquiry.

“Julio had heard the stories of her attack and recovery, and having seen the girl herself in golden repose, was convinced that Mariana had been blessed with a sacred vision. He longed to experience such a vision himself and spent long hours submerged in studies of the Cabala or chanting prayers in hopes of attaining a state of religious ecstasy.”

However well-intentioned, he wants to capture the mystical as if it were a tangible object, a rare butterfly he could swoop into a net and pin on a board. Many years later, he comes to understand that “. . . he had spent his entire adult life imagining Mariana–that she could be anyone, could be thinking anything, and he would never know. Is this how we spend our lives? he thought. Imagining each other?”

The decision by Raven Chronicles Press to reissue Spirits of the Ordinary seems prescient. These days racism is worn like a badge of courage; the practice of public hygiene is confused with the practice of free speech; and no politician who uses the word “antifa” seems to know what it means or read Mark Bray’s Antifa, a history of the anti-fascist movement that emerged in response to Mussolini and Hitler. These days, is there a better response than imagining one another through story? The border Alcalá describes gives the lie to authoritarian rants against Mexicans, against all Latinex people, whether immigrants or native born. Her work, like the work of so many Latinex writers, merits greater recognition as part of a US literary canon. If you are interested in Latinex writing, let me know. We can develop a reading list together. If you would like to know more about Alcalá herself, I had the pleasure of interviewing her recently. Look for that May interview at Fiction Writers Review.

Questions: What have you read this past year by Latinex writers? Do you consider Latinex writers as part of the US literary tradition?

Support local bookstores: https://bookshop.org/

[coffee]

What an interesting story. I pick up books because they promise me a good story and I’ve always enjoyed reading widely from different cultures (English translations). Until high school, I’d only read Indian or British authors. So what a wealth when I discovered American lit. My first non-American author was Pablo Neruda as part of a World Lit. class in high school. And I’ve read many more since. Last year, I got myself a bunch of picture books illustrated by Yuyi Morales; my favorite is DREAMERS. It’s her own story, beautifully written and illustrated. Thank you for introducing me to Kathleen Alcala’s work. I will look it up some more.

I forgot that I read Diary of Anne Frank when I was 10 in India. It remains such an important book.

Thank you for this post, Elizabeth. I love the pride and strength that always comes through in your words. We all need to be cognizant of that spirit, to make it a part of our writing, to be honest in our work and to treat one another with dignity. Thank you again.

Great post and I look forward to reading your interview. This novel sounds fascinating. There are few books about Sephardic Jews and their immigration to Mexico (which has a large population). I’ve had the opportunity to hear Kathleen Alcalá speak at conferences and she’s compelling. No doubt her novel will be too.

The books by Latinx authors this year have been: Crystal Maldonado (YA), Alda Dobbs (MG), Jacquira Diaz (memoir), and Kristen Millares Young (A).

I am one in principle – 1/4 or 1/2 Mexican, depending on how you count (long story) – and I always seem to have one character we used to call Mexican-American, both in the unpublished novel series, and in my current mainstream trilogy.

I grew up in Mexico – formative years from 7-19, close to my extended bilingual family.

But I’m more of a gringa with exposure – I had to deal with being the ‘other’ while growing up because I looked like my dad’s Hungarian side of the family, and was taller than the girls and most of the guys!

So I’d say of course part of the US literary tradition – but in English, as the US dominant literary tradition doesn’t include much written in Spanish. Most people who have read popular or literary fiction first produced in Spanish have read it in translation – and the differences are significant. Spanish takes more space – and more poetry – to say things, and there is a love of the harder, more complex vocabulary in the Spanish.

The nations where Spanish is spoken are quite different from each other. Immigrants to the US come from many different levels of society. I haven’t heard ‘Latinx’ used anywhere but here, but my sphere is quite small due to illness, so I’ve probably missed it.