Emma vs Hamlet: Two Approaches to Dramatizing Character Change

By David Corbett | March 12, 2021 |

No question so focuses the mind of a writer beginning to draft a scene—or the series of scenes that will comprise their story—as what do the characters want. The question instantly begs a slew of others: Why do they want it? Do they themselves know? How? With what degree of clarity, certainty, or honesty? What if they’re mistaken? Worse—what if they’re actively deluding themselves?

Or, as two of my favorite writers put it:

More often than not, people don’t know why they do things. ―William Trevor, “The Room”

She’d gone into real estate, she claimed, because she liked helping people find what they wanted, and she seemed blithely innocent of the fact that most people had no idea what that was, especially the ones who were defiantly confident they did. —Richard Russo, “Intervention”

This of course brings up all manner of murky ruminations about the role of the unconscious in behavior, the influence of denial, the insidious effects of bad faith, the power of persuasion—and barely have we begun than we find ourselves wandering the weeds.

The solution for a great many writers is to simplify by making the character clear about his desires, but making them extremely difficult to achieve. The question is never what the characters want; rather, it’s will they prove capable of obtaining it. This is especially true in stories where the major struggles are exterior, as in mysteries and many adventure stories, or in love stories where the interpersonal element minimizes the self-doubt aspect of the pursuit of the loved one.

In stories where a significant share of the drama plays out in the internal sphere, however, a fog all too often descends. This results from the fact that, absent a need to act or make a decision with real-world consequences, characters—like their creators—all too readily spin their mental and emotional wheels trying to figure what they want, what they should do, and why. This struggle is part of the drama, of course, and can be among the most affecting aspects of the story as long as it doesn’t digress into mental meandering or tedious navel-gazing.

In either event, the trajectory of the character pursuing some ambition, goal, or desire, regardless of how consciously, wisely, or honestly they do so, is what we often refer to as that character’s arc

As a practical matter, many writers (and not a few writing guides), follow a format that has the character at the story’s outset wedded to a wrong idea of what she wants or why, and allowing the struggle of its pursuit awaken the character to the folly of that desire and then discovering what it is they truly want, with the end of the story providing a gauntlet of reveals and reversals as the character now pursues her true desire with clear-eyed resolve.

Is it really that simple? Let’s discuss.

Generally speaking, the story arc dictated by the kind of thinking I’ve just described observes the following general format:

- The Protagonist enters the story in a state of Lack, in which she tries to strike a balance between her ambitions and frustrations, her achievements and setbacks, her joys and heartbreaks; that balance defines her way of viewing the world and her life.

- Something happens that prompts the Protagonist to act—specifically, it creates a problem she needs to solve. This may take the form of an opportunity rather than a misfortune, but soon enough the pursuit of that opportunity will prove problematic.

- The Protagonist’s state of Lack creates a mistaken understanding of the problem, what she needs to do to solve it, or both. This is because the Lack, rooted in a past typified by compromise, takes a greater account of those aforementioned frustrations, setbacks, and heartbreaks that hope for a genuinely better future will allow. It is often grounded at least partially in defeatism, cynicism, or the kind of “realism” that all often translates into: Grow up. The world isn’t fair. The only people who get what they want are cheaters, liars, and thieves. It may reveal itself in mere timidity, ambivalence, even “niceness,” but underneath there’s at least a shaky faith in the promise of life, if not outright apostasy.

- This mistaken understanding of the story’s core problem, or how to go about solving it, is sometimes referred to as the “Misperception” or the “Lie.” It is also often what is implicitly referred to when writers are advised to make what the character needs different from what he wants, i.e., what she wants is based on a misunderstanding of what she truly needs.

- This misunderstanding is rooted in the character’s fundamental resistance to change.

- By pursuing this mistaken understanding, the Protagonist takes many false steps, wanders down blind alleys, suffers many setbacks, and otherwise endures a series of failures, near misses, or half-successes that leave the core problem of the story unsolved. The educational process created by this series of mistakes and wrong moves is often referred to as “success through failure,” and forms the basic trajectory of the character’s arc.

- This series of missteps and setbacks ultimately leads to a moment of such drastic failure, often including the loss or death of a loved one or a close ally, or the prospect of death for the Protagonist herself, that it seems like total defeat is at hand. In the resulting “dark night of the soul,” in which the Protagonist searches her heart and mind for one last solution to the story’s core problem, she experiences an insight that reveals the nature of her original mistaken understanding.

- This new insight may include a greater awareness of her own personal investment in that misunderstanding, i.e., why it seemed so true and convincing and why she embraced it so wholeheartedly. If so, it is not merely her understanding that will change, but her own internal nature. She will realize that she herself must change to solve the problem. This revealing moment of self-awareness is often called, unsurprisingly if somewhat melodramatically, the “change-or-die moment.”

- This new awareness will prompt a decision by the Protagonist to change methods, change allies, and/or change herself in order to get one last chance to solve the problem. From that point forward, the question at the heart of the story will no longer be: What must be done? That is settled, at least as far as the Protagonist can determine at that point. The core question from that point forward becomes: Will the Protagonist succeed? That question will be answered in the climax.

The Protagonist may of course have more than one moment of transformative insight in the course of her numerous missteps and failures and partial successes; if so, they should intensify in depth, intensity, and surprise as the story proceeds.

The key such insight, the one that prompts the greatest change, technically can appear anywhere in the story, though it usually appears two-thirds or three-quarters of the way through the plot; otherwise the reader or audience may begin to wonder, if the Protagonist possesses sufficient insight into the problem and herself to make a decision as to what should be done, why it is taking her so long to do it? A reluctant hero’s dallying can be endured only so long.

The answer in such situations usually lies not in the difficulty of knowing what to do or lacking confidence in oneself but rather the number or severity of the obstacles in her path, i.e., the difficulty of the task or the ferocity of the opposition she faces from other characters. That said, one needs to be wary of merely stacking up dragons before the castle. Repetition undermines tension, and there are only so many struggles of similar type the reader or audience will sit through before growing restless.

This is why, normally, the greater amount of narrative time and space is spent depicting the Protagonist’s struggle to understand the problem, overcome her doubts as to what should be done and whether she is capable of doing it, subdue the internal forces holding her back from the challenge of positive change, and devise a plan for going forward that stands a decent chance of success. That effort offers the prospect of greater variety in action, emotion, and reflection, thus providing broader opportunity for variation in scene and thus surprise.

The preceding outline of a generic character arc enjoys the advantage of both sufficient clarity and flexibility to prove adaptable to most story types.

A classic example: Jane Austen’s Emma. When Emma, the match-making busybody, realizes that she is wildly mistaken in her beliefs about the other characters, she descends into a paralysis of self-questioning doubt. Mr. Knightly kindly guides her toward the truth, and the story comes to a happy end, with multiple well-paired marriages.

However, as gratifying as this format can seem, especially in the hands of a master like Jane Austen, it nonetheless has several obvious limitations. Put differently, if you are one of those who finds Emma’s transformation from supercilious meddling know-it-all to happy bride a bit magical, you’re not alone.

First, who among us would not be thrilled to learn that the solution of merely one problem or the correction of one mere misunderstanding cleared all storm clouds away and ushered us into an endlessly sunny future? Is this true to life, or just “true to stories”?

Second, by focusing on misunderstanding as the factor leading the character astray in her attempt to solve the core story problem, this methodology suggests that her error is fundamentally conceptual, i.e., one of belief or perception.

However, a character’s problem at the story’s outset typically goes beyond what she thinks; it is embedded in her behavior. And that behavior is itself embedded in habits that have been developed and engrained over time. They are second nature, often deeply unconscious, and changing them will require more than a new perspective or attitude.

Certainly how the character interprets her problem is part of that behavior, but it also encompasses how she treats others, how she acts under duress, how she responds to stress, frustration, anxiety, uncertainty, confrontation, terror—as well as how she handles kindness, assistance, trust, and support from others.

It is seldom the case that a single factor accounts for the character’s problem with her past. Rather, whatever weaknesses, wounds, limitations, or flaws she possesses often interact, influencing and enhancing one another.

Amplifying that point, pinning a character’s behavior to a single factor tends to diminish her in the audience’s or reader’s eyes. Rather, whatever problem she faces has to be seen to emerge from the whole of her personality.

As long as by misperception we include this broader concern not just with interpretation but behavior, the interweaving of influences, and the full complexity of the character’s nature, incorporating not just her thoughts or feelings but her physical reactions and habitual behaviors and moral worldview, the standard character arc outlined above can serve our purposes. But it will require a bit more heavy lifting than its tidy outline suggests.

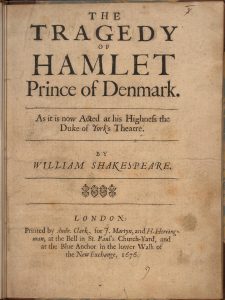

By now, however, I’m certain some of you will have already noticed another limitation of the character change format outlined above—if only because of my inclusion of Hamlet in the title of this post.

To the extent stories provide reassuring certainties in a world of relentless conflict, disruption, confusion, dislocation, etc., we should not bemoan too loudly our tidy formats and neat conclusions.

This is not mere escapism; by convincingly exploring what might occur, despite the odds to the contrary, we expand our ability to imagine what is possible. And to the extent our ability or willingness to act in the present largely rests in our hope for the future, imagining the possible is no small matter.

However, it is also true that in embracing the tidy and the conclusive, we turn a blind eye to what constitutes the real experience of the vast majority of humanity. Problems that get solved routinely engender new problems. Corrected misperceptions give rise to new views that, on further scrutiny, reveal their own shortcomings. Just as plans never survive first contact with the enemy, and scientific breakthroughs invariably suffer at the hands of subsequently observed data, so too with personal insights—no matter how clear-cut and incisive they might seem at first, reality has a way of dulling those sharp, shiny edges.

It might even be said that the desire for tidy conclusions is a socially acceptable form of death wish, because only death puts a conclusive end to things once and for all.

Instead, we all too often find ourselves in Hamlet’s shoes, weighing incompatible options, unable to decide, all too aware that whatever we choose the consequences are to some extent unpredictable, and that nothing will put a definitive end to our “problem.”

A more modern example is the film Michael Clayton, written and directed by Tony Gilroy. The eponymous main character is faced with a crucial moral test he at first fails, then he rectifies his error with a climactic confrontation with his adversary. And though the audience gets its catharsis, the character does not. The final scene shows him disobeying his detective brother’s advice to stay near and instead getting in a cab and asking for “fifty dollars’ worth.” We then watch him alone in the back seat of the cab as it traverses the streets of New York. His facial expressions reveal a cascade of conflicting emotions (similar to those of the Bob Hoskins character in The Long Good Friday, the ending of which provided the inspiration for Gilroy), telling the audience that the story is far from over—he might regress, he might face a slew of crushing circumstances from a number of directions because of his decision “to do the right thing,” he will forever be looking over his shoulder.

The arc in such stories often tracks with the one discussed above, except that the element of doubt never evaporates. Instead of Emma’s, “Oh now I see,” the character instead thinks, “What if I try this?” Good news—it’s by no means less suspenseful. Like the character, the reader will be wondering if the new path will lead somewhere useful, not the edge of a cliff. But there will be readers who find even that modicum of ambiguity unsettling. If they want uncertainty, they can look out the window.

Final observation: Although Emma is a satire, a genre known for its artificiality, that alone does not explain or justify its use of a simpler, more direct dramatic format. Tragedy can do the same—ask Oedipus, or Tosca. Form alone does not dictate to what extent ambiguity and uncertainty play a part in the degree to which a character changes. That’s entirely up to you.

How do you go about portraying your characters pursuing the wrong thing, or pursuing it for the wrong reasons? Have you used the “misperception” character arc? Specifically, how did you show the character “succeeding through failure”? What form did that success take? How did that approach work for you? If it didn’t work, why? How?

Have you ever made your main character’s decision-making more ambiguous or open-ended? How did that turn out? Did you find yourself getting pushback from readers, agents, or editors, who wanted a more clear-cut process and a more conclusive ending?

In my WIP, my hero’s problem is that he’s not a hero. He’s a bystander, a helper and protector of a girl with an extraordinary ability. He’s in love and when (through plot circumstances) she disappears, he is shipwrecked. He knows they will meet again, she said so, but he must wait…as it turns out, for eight years.

Challenges for me were finding my hero’s arc and making waiting heroic. However, that has been done by Audrey Niffenegger and John Fowles, among others, so I knew it was possible just, at first, not how.

I solved the arc problem by not pre-defining the arc but simply putting myself in his shoes, asking what I would really do and feel if that were me, taking it naturally, and lo it came together. His change comes about not because he’s been pondering it or trying this or that but because at last he was ready to take action—and become a hero, as much for himself as for her.

What you are talking about today, I think, is the natural movement of the human heart, which yearns, ducks, weaves and at some point finds its way to courage and happiness and change. It’s a journey you can’t always plan, you just have to take it, ask me.

Thoughtful post, David, thanks.

For some reason, Benjamin, your comment, which was the first one made by anyone, only showed up just now. Which is a damn shame because it’s really excellent and insightful. I can only imagine what a challenge that problem was, and good on you for being willing to follow your own instincts. Sounds to me like your hero and you both share the courage of patient persistence in pursuit of the right time, the right thing to do. Bravo.

Hi Everyone:

This is turning into an odd day. Our older dog, Hamley, had surgery to remove a growth on his paw yesterday, and just now we discovered a growth on the paw of the pup, Fergus. Strange coincidence, I guess. So I may be on dog duty much of the day. I will check in as often as I can, and hopefully have the time to respond to any comments, but it may be later in the day. Thanks for understanding.

Such a good post. Deep stuff to think about. I’m so glad you have the “print this post” option so I can study the material in depth right.

Thanks, pal. Hope all is good on your end.

Thought-provoking post. I can’t help being reminded of Kurt Vonnegut’s Sirens of Titan. His character’s journey to the meaning of life is fraught and finally, he stands at the cave of the Sirens pulls back the curtain to reveal the phonograph that plays the sound of their mannequin voices to find scribbled on the wall at the back:

“I was a victim of a series of accidents as are we all.”

This pandemic has put a lot into a new perspective for me and solidified some of my suspicions about writing.

What came first, institutional programming or the writing that supported the totally man-made institutional proper way of life?

I’ve always hated Austin for the *right-proper* system she upheld and I rooted for the females she painted as Villians.

And I think perhaps a lot of writing instruction falls into the Austin trajectory to work.

But I’m starting to ramble.

Thank you for your post being a catalyst to something I am still trying to uncover.

That’s AustEn. I’ll give her the respect of spelling her name correctly, even if I don’t respect her work.

“I was a victim of a series of accidents as are we all.”

There’s a post in and of itself.

A story based on that logic would of course lead to the dreaded episodic plot. You know, like life.

And there you have it. Stories aren’t about life, they’re about but an idea of life abstracted from episodes where something dramatic does indeed occur. I often call them “conscience experiments,” asking the reader to follow along as the characters are challenged to act in response to interesting events, with the implicit question: What would I do in similar circumstances?

Glad I could help in any way to be a catalyst to something you’re still trying to uncover. That sounds rather dramatic as well — and fascinating. Good luck. And thanks for chiming in, Bernadette.

Thank you.

FYI: your posts always inspire and challenge me to dig deeper and think from different angles. I learn a lot from you and appreciate it.

Thanks for the attaboy, Bernadette.

Bernadette, I am a Jane Austen fan, but I think I understand your dissatisfaction concerning her “right-proper” female characters. This subject was discussed by the mother and daughter characters in One True Thing, a novel written by Anna Quindlen. The mother thinks that only “bad” females are written about (and celebrated) because “good” ones are considered boring. Jane Austen heroines usually act against what is expected of them at some point in the narrative. They’re feisty, but only to a degree.

Yep. Austen’s heroines are feisty within the confines of the time’s status quo and only in the way the status quo of the time considered *virtuous feisty*. On the other hand, all of Austen’s FEMALE VILLIANS are considered horrible characters for trying to survive by their wiles within that status quo with what life has dealt them.

I remember having a discussion about this in an English Lit class years ago when we were dissecting Northanger Abbey.

Two female writers who consistently send damaging messages that uphold the status quo IMHO are Jane Austen and Ayn Rand.

And that leads me to question a lot of what I’ve been taught both about life and writing.

Wow, putting Jane Austen and Ayn Rand (Nietzsche for Dummies) in the same cabal. I see what you’re saying, but, yeah. wow. Now THAT is a topic for a post all its own.

Yep. Think about it—two female writers who helped to uphold the patriarchy’s narratives with their stories…

One did it with perfect manners. The other did it with a flame thrower. One was a beautiful stylist. The other wrote turgid, gaudy, unreadable prose. One is still remembered as a great artist. The other is increasingly recognized as the architect of a house of cards that is currently falling down all around us.

A lot of stuff comes to mind here:

The end doesn’t justify the means.

The devil often appears as an angel of light.

I could go on and on… down the rabbit hole.

Austen is just starting to be reexamined, tho’, and that’s a good thing.

Very helpful post – I appreciated the clarity with which you break down the internal-conflict character arc. And I liked the reminder that it’s not the only valid path, just the most well-worn one and one that readers find comforting. It’s good to know how to do it well – I’m still learning that – and good to be reminded that we should question the familiar structures that are common to so much writing advice.

David, I’m currently writing a story about a character who is actively deluding herself. Your post has reminded me to write that delusion into everything she does while pursuing her goal, and not let the truth accidentally slip out before the climax. Thank you.

I hope Hamley has a speedy recovery and that Fergus is well. Are they related? It’s strange that they both have growths on their paws. Is Hamley the one who came to Boise with you and Mette when you arrived during the frightening thunderstorm?

Yes, Hamley came to Boise with us. Fergus is the new kid on the block. And yeah, it is strange, isn’t it?

David, there is so much in this post, and it’s been a day of crazy running around for me, so let me focus on this: “It might even be said that the desire for tidy conclusions is a socially acceptable form of death wish, because only death puts a conclusive end to things once and for all.”

Your statement could be a call for a literature that though unsatisflying to some, provides unanswered questions. Much of literature can be entertaining, but it can also be a stimulus for examination, for realizing something within ourselves that is lacking, ie your reference to the Michael Clayton character. There are moments in Emma, when she realizes her faults. Hamlet is tortured by his. And “yes” to ambiguous decision making in a novel. At the end of the day, there is always an opportunity to tidy up questions, but to then realize that there are often an unending number of answers.

Another example that came to mind as I was reading your comment, Beth, is the final scene in The Graduate. Again, they’re moving in a vehicle — a public bus this time — but their expressions tell you that, though the couple have just committed a mad act of daring, running off from the beautiful wedding the bride’s family had planned, leaving the hapless groom at the altar, there’s no guarantee their adventure will end well. They both seem to be thinking, “What now?” If not, “What they hell did we just do?” I think there are plenty of open-ended stories like this, as well as stories where the crucial insight isn’t definitive, it just seems like the only viable option at the time, and it has its own problems that leave the reader wondering what the characters will be doing beyond the story’s end. And readers have embraced such stories. I just wanted to counter an approach that has been getting a bit of the this-is-the-one-and-only-way treatment and remark that there remain other options. Thanks for the comment!

“as long as it doesn’t digress into mental meandering or tedious navel-gazing.” I’ve just finished the first draft and in the process of combing through the weeds of the second pass to work through it all. I quoted your phrase because I’m reminded of Philip Roth and some other classic navel gazers I admire. May I put James Salter, Richard Ford and John Williams in that bucket? Your post reminds me of how valuable your book Compass of Character is. The hero’s journey can follow many routes to its final success. Thank you for being such a good compass!

Thank you for the insights, David.

I solve my this issue by working with three arcs:

1) Dramatic Arc – which deals with the Core, overarcihng Conflict of the Story.

2) Emotional Arc – which deals with the Protagonist’s wishes vs. desires, and leads to the Self-Revelation during the Resolution, that ends in the Climax.

3) Thematic Arc – which deals with the … yes, thematic aspects of the story.

Depending on the type of core conflict (Mental, Emotional, Physical), the Protagonist will resolve that core conflict in a satisfactory manner (either “happy” or “sad” ending), but at the cost of one of the above-mentioned Arcs. In other words, a gain is a satisfactory gain, but there’s always a loss of some sort involved, not necessarily a definitive loss, but the clarity that there is still something to be resolved (life goes on and not necessarily in a clear, direct line).

It irks me when, for the sake of “alternative, open, or ambiguos” endings, the Core Conflict is left unresolved. In this way, the story comes to a closure through a New Equilibrium, that is definitely related to this story, but human existence continues without a sense of an absolute happy or sad ever-after.

Don’t know if this makes sense.