Still Crazy After All These Years

By Guest | March 8, 2021 |

We are thrilled to bring back longtime contributor Lisa Cron for a guest post today! When we learned that Lisa had a new book coming out, STORY OR DIE, we knew we’d need to get her back here for a guest post. Turns out, she was as happy to be back here as we were to have her. And in case you’re new to WU, or don’t know Lisa, let’s fill you in:

We are thrilled to bring back longtime contributor Lisa Cron for a guest post today! When we learned that Lisa had a new book coming out, STORY OR DIE, we knew we’d need to get her back here for a guest post. Turns out, she was as happy to be back here as we were to have her. And in case you’re new to WU, or don’t know Lisa, let’s fill you in:

Lisa Cron is the author of Wired for Story, Story Genius, and Story or Die. Her TEDx talk, Wired for Story, opened Furman University’s 2014 TEDx conference, Stories: The Common Thread of Our Humanity.

Lisa has worked in publishing at W.W. Norton and John Muir Publications, as an agent at the Angela Rinaldi Literary Agency, as a producer on shows for Showtime and Court TV, and as a story consultant for Warner Brothers and the William Morris Agency. Since 2006, she’s been an instructor in the UCLA Extension Writers’ Program, and she has been on the faculty of the School of Visual Arts MFA Program in Visual Narrative in New York City.

Lisa is frequent speaker at writing workshops, universities, and schools, and in her work as a story coach she helps writers, journalists, educators, business leaders, social justice advocates, and change makers master the unparalleled power of story. She can be reached at www.wiredforstory.com. Follow her on Twitter @lisacron

Be sure to check out our archive of Lisa’s posts HERE.

Without further ado, a WU spin on a topic covered in her latest book, STORY OR DIE.

Still Crazy After All These Years

Long time! I’ve missed you, because writers (you guys) are the most powerful people on the planet, and nothing is more intoxicating than talking story. Or, I admit in my case, more incendiary. So, let’s play with matches.

Remember back in college, that lit professor who started every lecture, “In literature as in life…” She was right. Way more than even she realized, I’d wager.

Because as Jonah Lehrer’s book title neatly sums up: Proust was a Neuroscientist. But what does that really mean?

Just this: an effective story mirrors life – our inner life that is – which is precisely why we turn to it. Thus it’s imperative that the protagonist, all characters in fact, have brains that operate the same way ours does. Story is built into the architecture of our brain, and so it must be in theirs.

Especially since we are wired to come to story hunting for insight into how people – real people, people like you and me and that weird guy over there — think. Not what they say, not what they do. But why.

After all, we can see what people do, we don’t need a story to show us that. The question we’re always asking is “WHY? What on earth were they thinking?” Heck, it’s what we’re always wondering out here in real life, and now more than ever.

Story’s goal – and the reason we’re drawn into a story to begin with — is to answer that question. Here’s the thing: our brain automatically knows that’s what we’re looking for, even though, consciously, we don’t. It’s not a choice, it’s not something we’re taught. It’s biology.

The Writer’s Misbelief: The Two Most Damaging Writing Myths

And here’s the irony: precisely because we don’t know what’s really hooking us, writers are often taught not to do the very thing that the reader is wired to instantly hunt for and respond to.

Myth Number One: Don’t give us internality. Don’t tell us what the character is thinking.

Myth Number Two: And whatever you do, if you have to give us backstory, do it sparingly, when the reader needs to know something.

Wrong, wrong, wrong. A hundred times wrong.

The Truth: Brain Science Edition

This is something I thought about a lot as I wrote my new book, Story or Die: How to Use Brain Science to Engage, Persuade, and Change Minds in Business and in Life. I spent the past couple of years diving deep into current neuroscience research, into evolutionary biology, into social science experiments – and the scientific evidence on what pulls us into a story is pretty definitive. And thrilling. Because it gives writers clear guidelines about what we need to get onto the page. And what we need to create first – backstory — in order to have something to get onto the page at all. (You know I want to point out here that this is precisely why neither pantsing nor plotting work. I’ll refrain.)

First, let’s talk about memory (aka backstory). As neuroscientist Dean Buonomano makes clear in Your Brain Is a Time Machine, “Memory did not evolve to allow us to reminisce about the past. The sole evolutionary function of memory is to allow animals to predict what will happen, when it will happen, and how to best respond when it does.”

In other words, without story specific memories, how can your protagonist (or any character) figure anything out, at all? The answer is simple: they can’t.

We all use the past – our subjective past — to make sense of the present. For heaven’s sake, all that stuff we did in the past is what landed us where we are in the present – you know, for better or worse. Without access to our past memories we’d all be walking around with amnesia, trying to figure out how we got here (and coming up blank). And, probably, wondering how the heck things got so messed up. But that’s another, um, story.

Tucked into Buonomano’s statement about memory is another piece of great writing advice: do not have your characters simply reminisce about the past – because that is not what memory is for. Plus, it’s boring, and likely an info dump – in literature and in life. Rather, characters use memories to figure out how to make the tough decision that each and every scene will force them to grapple with. And that inner struggle – yes, what they’re thinking — is where story logic comes from. Story logic is the subjective, evolving logic the protagonist uses to make sense of the things that happen (aka the plot). That internality is what gives voice to backstory, and is woven into every single page.

And that is what readers (aka all of us) are wired to instantly look for in every story we hear. Whether it’s as short as a headline, or as long as the novel that the protagonist (picture Michael Douglas here) was writing in Wonder Boys.

But, again, this tends to fly in the face of what writers have been taught. Starting with Aristotle. Who has fooled a lot of people, including Steven Brown, director of the NeuroArts Lab in the Department of Psychology, Neuroscience & Behaviour at McMaster University in Canada.

Brown designed a study to see what area of the brain instantly lights up when we encounter a story. In other words, what do we innately look for, what hooks us, what makes us care.

He thought he’d find proof of what Aristotle said about story. “Aristotle proposed 2,300 years ago that plot is the most important aspect of narrative, and that character is secondary,” he said.

But what he discovered is that, contrary to popular belief, our brain is on the lookout for something else altogether. “Our brain results show that people approach narrative in a strongly character-centered and psychological manner, focused on the mental states of the protagonist of the story,” he said.

And not just in novels. After all, story existed eons before novels, memoirs, and all those shows we avoided back in the day but are now binge watching because, hey, it’s been a year, and we’re still stuck inside.

Brown’s study didn’t monitor the brains of people leisurely reading a novel or munching on popcorn while watching a movie. Rather, study subjects read short factual headlines, like “Surgeon Finds Scissors Inside of Patient” or “Fisherman Rescues Boy from Freezing Lake” to see what areas of their brain would activate as they made sense of it—that is, as their brain did what brains naturally do: translate the headlines into a narrative. The result? The second they saw the headline, what sprang into action in their brain were the “components of the classic mentalizing network involved in making inferences about the beliefs, desires, and emotions of other people as well as oneself.”

In other words, our brain is empathizing, and we don’t empathize with the plot, we empathize with the characters.

According to Brown, when we’re grabbed by a story, we’re instantly making inferences about the protagonist’s beliefs in order to pinpoint their intentions and what is motivating their actions. We’re not hooked by what the protagonist is doing; we’re on the hunt for why they’re doing it.

Marcel Just, director of the Center for Cognitive Brain Imaging at Carnegie Mellon University, agrees. “One of the biggest contributions of brain imaging is to reveal how intensely social and emotional the human brain is. To me it was a very big surprise. Ask people to read some innocuous little narrative, and the brain activity shows that they’re computing things like the character’s intention and motivation. I think there is a constant tendency to be processing social and emotional information. It’s there, and it’s ubiquitous.”

Not to put too fine a point to it, oh what the hell, why not? So, as Brown said, summing up the results of his study in the Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, in our brain: “narrative production is more associated with character than plot, despite the field of literary studies prioritizing plot over character since the time of Aristotle.”

Indeed. Okay, my work here is done.

Takeaways:

- The protagonist’s internal struggle is what the reader is hardwired to seek out, it’s innate. Pretty writing, or rip roaring “objectively” dramatic events are utterly boring without it.

- Memory – backstory – is what protagonists (read: us humans) use to gauge the risk of everything they do. Backstory explicitly drives what they’re thinking, in the moment, on the page — it’s the “why” that causes them to take the action they do. And what the reader comes for.

- The narrative throughline is not the plot. The narrative throughline is the evolving internal narrative that the protagonist uses to make sense of what’s happening.

- A story is not about an external change, it’s about an internal change, within the protagonist’s belief system. In a nutshell: A story is about how an unavoidable external problem forces the protagonist to change internally in order to solve it.

I keep instinctively writing flashbacks for my MC in my WIP. Some of them I know inform a chapter, but with others I wasn’t sure why I wrote them. Your post has given me a guide. Wow, exactly what I needed. Thank you!

This stands out to me:

“… characters use memories to figure out how to make the tough decision that each and every scene will force them to grapple with. And that inner struggle – yes, what they’re thinking — is where story logic comes from. Story logic is the subjective, evolving logic the protagonist uses to make sense of the things that happen (aka the plot).”

Sounds like you’re on the right track, Ada, and that puts you miles ahead of the pack — yay!

Lisa, Thank you! Downloaded immediately! I’ve adored your presentations at WU Unconferences and, of course, you’re previous books. So looking forward to digging into this one.

oops! “Your” of course.

Thanks so much, Densie, you made my day and then some! I have such fond incredibly memories of the WU Unconferences myself ;-).

Lisa, it’s so great to see you back here!! And thank you for the mini-masterclass. There’s so much here, not the least of which is this. “…in other words, our brain is empathizing, and we don’t empathize with the plot, we empathize with the characters.” Understand and internalizing all of this will not only make y us better writers, but possibly better human beings. I’m looking forward to reading the new book. Hope this finds you well.

Thanks so much, Susan, I’ve missed this back and forth on Writer Unboxed so much! And same right back at you — such a strange time, isn’t it?

Lisa, I read Story Genius and enjoyed time with you at the WFWA Retreat. But this post today is confirming the direction I have been taking with my novel. I know how I deal with emotion, problems in my own life–sometimes looking backward, trying to piece together the reasons for the choices I have made or how to counsel my children when they have major decisions to make. So what would be wrong for my characters to do the same thing. Like life, ideas evolve, though I believe when one holds a book like the Great Gatsby as a favorite, isn’t Nick Carraway telling us about events through his own sorrows, joys and confusions? Thank you.

Thanks Beth, I have such fond memories of the WFWA Retreat, which these days feels like a million years ago, especially considering that the past year was about a decade long. And exactly! So much backstory, and so many seeds that will grow throughout Gatsby, just buried right there on page one. It never gets old, does it?

Thanks, Lisa, this comes at a perfect time for me. I’m writing a short story that fills in some backstory via a storytelling-within-the-story kind of approach. (How many times can I pack “story” into one sentence?) I’ve been feeling a little unsure about pulling away from the present to chase down the past, but the point of it (I think; I’m never totally sure) is really to chase down the protag’s motivation for what he’s doing in the present. So I’m feeling a little more confident about it after reading this. (A *little* more. A little.)

Also, Wonder Boys = a movie I enjoyed more than the book. It’s such a pleasure to watch.

Ha, exactly! I just came across what I think is a brilliant quote from Kazuo Ishiguro (I’m about to start reading his latest, Klara and the Sun). Anyway the quote is: “What I’m interested in is not the actual fact that my characters have done things they later regret. I’m interested in how they come to terms with it.” In other words, the story is always, always, about the meaning the character reads into what’s happening, rather than just the “action.” And, truth is, when you’re in the character’s head, there IS action, because the memory of the event they use to make sense of what’s happening in the story present, IS an event itself.

Liberating. And energizing. Thanks … I think ;)

Love it! Reminds me of an old Mother’s of Invention lyric: “I’ll love you forever, I’ll love you forever, I’ll love you forever . . . I think.”

First, Lisa, I’d like to say OMG. This post is like a brain-sieve, distilling the message I pass to clients on a REGULAR basis.

As a professional editor who specializes in manuscript evaluations and developmental editing, I see this breakdown in understanding all the time. Writers struggle with the connection between a character’s backstory, thought-process, motivation, and action. Yet, these are the very threads that strengthen a story–EVERY story.

You’ve done a wonderful job of connecting these dots in a manner writers will understand. Thank you! I will pass this post along to many great writers wanting to improve their craft.

Hugs

Dee

Thanks so much, Denise, that means so much coming from you! And (socially distanced) huge hugs right back at you ;-)

Thank you so much!! I have loved your previous books and can’t wait to dive into this one.

I just finished line edits on my next release and aside from some repeated words or phrases, the editor’s comments boiled down to “what is he/she feeling?”.

As I work on my next ms, I’m going to study this blog post carefully.

Thanks so much Carrie! And yeah, what the reader comes for is how the protagonist is making sense of what’s going on, in the moment, on the page–which is where all emotion comes from; you never have to tell us how they’re feeling, if we are in their head as they figure it out, we’ll automatically feel what they feel. Here’s to the power of story — yours!

Hi Lisa, great to see you! And thrilling to learn you’ve got a new book coming.

As I’m sure you have too, in workshops I have noticed that the hardest thing for fiction writers to is incorporate the interiority of characters: what they’re thinking and feeling and why. So often they hear, “that’s slowing the pace”. It’s the stuff they are advised to cut.

Now, as you–and science–have shown, it is precisely the interior world of characters that we readers seek. However, what I would add to your awesome post–and which I have no doubt you elaborate in your book–is that any old thoughts and feelings will not work. Hand-wringing, regurgitating, obvious emotions and hackneyed language invite the reader to skim. There is no intrigue to that.

At the same time, while understanding the why of characters is critical–their backstory is what drives them, after all–that discovery is in service of the fore-story: what characters must grapple with and do. Aristotle put all emphasis on plot. Today, we know that’s misleading. There is an entwined, symbiotic relationship between outer actions and inner state. Striking a balance between those, ask me, is the ideal.

Fiction is not psychotherapy. Psychotherapy itself unwinds past traumas in order to make life more livable in the present. It helps people go about the things they need and wish to do. We think and feel all day long, true enough. We are absorbed in ourselves, yet we must also wash the dishes and save the world.

I feel coffee if not drinks coming on. So much to discuss! When will we get to see each other in person again? Until then, I will have to content myself with Story Or Die. Heaving over to order my copy now. Welcome back to WU!

I love typos! Heaving? Heading. But then, heaving is accurate enough in this early-coffee hour…

Totally agreed! It is a balance between inner struggle driven by backstory and plot — or as I like to say, between story and plot. But the story is the driver, meaning, it’s not about what a character does, but why. And, ahem, in literature as in life, the why always comes from the past. Another Kazuo Ishiguro quote I’ve fallen in love with is:

“As a writer, I’m more interested in what people tell themselves happened rather than what actually happened.” Exactly! Or, as another brilliant storyteller said (okay, it was my son, Peter, who’s a filmmaker): The story present is what makes the unconscious, conscious. Meaning, the goal of the plot is to force the protagonist to question long held beliefs that, up until then, seemed to keep them safe. Which is why the narrative throughline is the protagonist’s evolving narrative — or as Ishiguro said, “what people tell themselves” about what happened. And YES, coffee is in order, and my hope is to be in NYC in July. (Sheesh, just hoping to be anywhere that isn’t my house is thrilling. What a year!)

Lisa:

Your advice jibes with what many other WU sages have urged: backstory, like every story element, should be used only if it contributes something to the narrative, if it advances the readers’ interest and understanding. Thanks for explaining why.

Indeed! Backstory is laced onto every page, as the protagonist struggles, in the moment, with the choice the scene is forcing them make, and leads to the scene’s “aha moment.” Otherwise, it just gets in the way, no matter how beautifully written.

Thanks so much, Lisa. I may have told you this already, but Story and Story Genius were game-changers for me in terms of figuring our where to go with my WIP. What I was missing after five of six painful revisions was the main character’s misbelief. Once I identified that, everything fell into a place and I am now querying my novel. I also did a TED Talk in graduate school based on how organizational leaders should use story to motivate their staff. And, I drew on the lessons from Wired for Story. I can’t wait to read your new book. Thanks for an insightful post.

Thanks SO much CG! Nothing makes me happier than to know that, in some small way, I’ve helped someone zero in on the heart of the story they’re telling — whether it’s a novel, or the story they’re using to bring people together to accomplish a goal. Keep me posted! ;-)

Wired for Story. Sorry for the typo. My mousepad jumps all over the place and erases words without my consent.

I couldn’t love this post more. I’ve shared it on my socials, in a writers’ group I’m a member of, and it’s going in my next editorial newsletter. For YEARS I have approached editing from this angle–that what makes us engage in story is when we care about the PEOPLE in them, which makes us care about what they care about and invest in why they do what they do. Love the way you articulate it, Lisa–and the science that supports it.

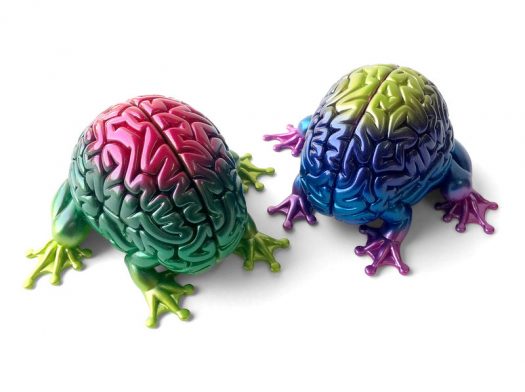

Also, side note, I think this is my favorite stock photo EVER. :)

Thanks so much, Tiffany! My goal is always to bring to light what stories are actually about, the better to hook the reader (not to mention change their life). It’s not theory, it’s science, which is another way of saying, it’s simply what we’ve discovered in terms of how we’re wired. Personally, I find it thrilling — must be that I’m wired that way ;-). And as for the stock photo — that praise goes to the brilliant Therese, who picked it.

Thank you, Lisa. I’ll be diving back into Story Genius as I resurrect an old MS and begin writing again!