Sherlock Holmes, Professor Moriarty, and Me

By David Corbett | December 11, 2020 |

I doubt I’m the only Unboxer who has accepted an offer to write something while having no idea whatsoever how I was going to get the job done. The process of feeling my way from that conceptual blank page to something worth reading provides what is quaintly referred to these days as “a teachable moment.”

Allow me to explain.

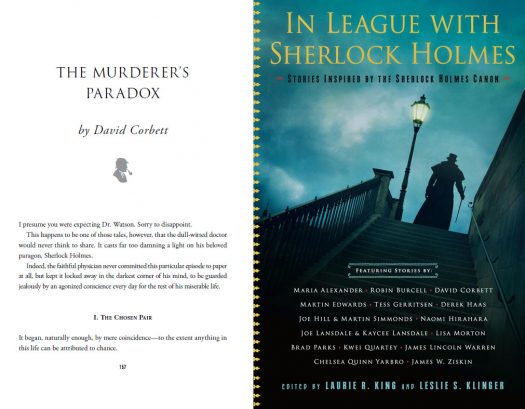

Last fall, I was asked by Leslie S. Klinger and Laurie R. King if I would like to contribute something to their periodic anthology of stories based on Sherlock Holmes.

This is a plum assignment. Les Klinger is an internationally recognized Holmes authority (editor of both the three-volume The New Annotated Sherlock Holmes and the scholarly ten-volume Sherlock Holmes Reference Library), and Laurie King is the author of the bestselling and critically acclaimed series featuring Mary Russell, protégé and eventual wife of Sherlock Holmes. They know their onions. And they do not suffer fools.

The anthology (there have been five editions so far) features writers of the first rank—this edition is no exception, as the list at the end of this post bears out—it routinely gets widespread notice, it has earned a loyal and growing readership, and it typically earns stellar reviews. There are no constraints on the author’s imagination—there have been futuristic Sherlocks, medieval Sherlocks, women Sherlocks, feline Sherlocks—you get the idea. Not even outer space is out of bounds. Who wouldn’t say yes to such an intriguing offer?

One problem. At the time I accepted this assignment, I had the somewhat unique distinction among writers in my genre of knowing next to nothing about Sherlock Holmes.

That, of course, didn’t stop me from saying yes, adding boldly that I intended to write my story from the perspective of Holmes’s arch-nemesis, Professor James Moriarty.

Second problem. I knew even less about Moriarty than I did about Holmes.

Fortunately, my lovely bride is an avid fan of the entire Holmesian oeuvre, and in particular has the entire set of BBC Radio’s full-cast dramatizations of The Complete Conan Doyle Sherlock Holmes.

This proved a godsend, since I doubt I’ve read a Sherlock Holmes story since high school, and I’m fully aware that recent film and TV adaptations have been, shall we say, less than canonical. And what I intended to write was a classic bit of Holmesian fiction, just from a point of view that, to the best of my knowledge, had never been attempted: that of his most famous adversary.

Third problem. Moriarty, for all his Machiavellian notoriety as “the Napoleon of crime,” appears in scant few of Conan Doyle’s stories, and the information concerning him is not just spotty, it’s at times contradictory.

Good news—this meant I could let my imagination run wild.

Bad news—no, I really couldn’t. It’s like turning Moses into a surfer. There are limits, even when they tell you there aren’t.

So who is this criminal genius?

Curiously, he was created principally as a device to kill off Holmes; Conan Doyle wanted to move on to other projects. This “death” occurred in “The Final Problem,” set in 1891, in which both Holmes and Moriarty fall to their death from Reichenbach Falls in the Bernese Oberland region of Switzerland.

Conan Doyle’s murder of his most famous creation proved short-lived, of course, as the public outcry was deafening. Both his fans and his publisher demanded the corpse be brought back to life.

Beyond that, Moriarty is mentioned offhandedly in only a handful of other stories—though a mastermind, he typically has others carry out his diabolical schemes. One story, however, “The Adventure of the Empty House,” takes place in 1894, three years after the supposedly fatal episode at Reichenbach Falls, indicating Moriarty as well as Holmes survived. This freed me up temporally, meaning I could set my story at virtually any time I wanted (within, ahem, reason).

The most instructive of the stories mentioning Moriarty was The Valley of Fear, which was based loosely on the Molly Maguires of Pennsylvania coal country and the undercover Pinkerton agent, James McParland, who infiltrated them, leading to the arrest and execution of their leaders. (The Molly Maguires are seen by many—though notably not Conan Doyle—as heroic forebears of the union movement.)

This information provided several themes that I decided to explore:

- Moriarty, an Irishman, has connections to Irish republican rebels in both America and Europe.

- Moriarty uses Holmes’s obsession with finding the truth to get revenge on a man Holmes hoped to save but ended up exposing through his relentless investigation.

- Moriarty is a mathematics professor at a small British college, famous for “a treatise on the binomial theorem.”

With all that in mind, I developed three key ideas I intended to use in my story:

- The Irish angle would play a major role.

- Moriarty’s scheme would involve turning Holmes’s obsession with the truth against him.

- In advancing his scheme, Moriarty would employ a mathematical puzzle both as a kind of signature and to incite Holmes’s curiosity. (Thus the title of my story, “The Murderer’s Paradox,” which is a variation on a famous paradox first presented by Bertrand Russell around the same time as the events of my story, i.e., the first few years of the Twentieth Century.)

As I continued researching, however, I also discovered a few other tantalizing avenues worth exploring:

- In 1902, Conan Doyle wrote a famous and full-throated defense of the British cause in the Second Boer War titled The War in South Africa: Its Cause and Conduct. This was meant to counter arguments being made that the war was nothing but imperial aggression meant to wrest control of key mining concerns in the region, and that British troops were guilty of atrocities.

- Emily Hobhouse, a delegate of the South African Women and Children’s Distress Fund, visited the British internment camps in South Africa—the first to be called “concentration camps”—in which women and children, both Boer and African, suffered under cruel conditions, leading to the deaths of tens of thousands. Her report on what she discovered in the camps became the basis of a government effort to improve conditions there.

- Conan Doyle, who for a brief time served as a surgeon in one of the camps, considered Emily Hobhouse an ill-informed alarmist and dismissed her findings out of hand.

- Subsequent investigations revealed the British officers in particular were not only involved in the sexual exploitation of young women in the camps but black market trafficking of medical supplies meant for internees.

- Some of the British troops were Irish, and they suffered disproportionately high casualties due to their deployment at the forefront of assaults against heavy enemy fire.

- There were Irish irregulars fighting on the Boer side, led by a dashing Irish-American cavalry officer who fought under General Crook and helped chase Geronimo into Mexico.

This gave me perhaps the most unique idea I decided to use: I would place Conan Doyle himself in the story. Moriarty would use two protestors against Conan Doyle’s defense of the war—a former nurse in the concentration camps and an Irish ex-soldier—as his pawns in a scheme against decommissioned officers who were now making use of their previous deployment to get rich, seeking out investors for a Transvaal diamond-mining concern rivaling DeBeers.

As you can imagine, there were times I found myself drowning in research rather than writing, all for a short story, not a novel. And devising a plot worthy of the Holmes canon while juggling so many balls at once took some fancy footwork.

Basically, the process I followed, from having no clue what to write to drowning in research to producing something I hope is worth reading, was the same as what the author James M. Frey describes as his Ten Rules of Writing:

- Read

- Read

- Read

- Write

- Write

- Write

- Suffer

- Suffer

- Suffer

- Don’t use too many exclamation points.

If you would like to know more about In League with Sherlock Holmes, you can go to this link. It really does collect contributions from a wonderful array of writers:

Maria Alexander, RobinBurcell, Martin Edwards, Tess Gerritsen, Derek Haas, Joe Hill, Naomi Hirahara,

Joe R. Lansdale, Kasey Lansdale, Lisa Morton, Brad Parks, Kwei Quartey,

Martin Simmons, James Lincoln Warren, Chelsea Quinn Yarbro, James W. Ziskin

Have you ever accepted a writing assignment with no idea how you were going to accomplish it? How did you find your way to a finished product? How did it turn out? Was it an ungodly mess? Did it instread end up being one of the best things you’ve ever written? Somewhere in between?

Hi David, this is a great glimpse into the creative process and how it unfolds, even on deadline and from a stone-cold start. I love James N. Frey and his “rules”—interestingly enough, he’s the only other writer I’ve seen expose a similar process.

Frey was at The Write Stuff conference in Bethlehem, PA in 2009, I believe, giving a two-day workshop in which he led 40 attendees through the group plotting of a novel, from choosing genre (it ended up a thriller) to orchestrating a cast, to creating a chart for what the reader will see happening with one character while the plot is advancing behind-the-scenes with others.

As conference chair, I had hired him, and so I read the silly evaluations, some of which said things like “it would have been better with handouts and a PowerPoint.” Only a few seemed to appreciate the informed creation that just occurred as Jim accepted, probed, or discarded ideas from the audience (the hive mind being our only research source for the Amish setting chosen), letting us in on his reasoning. Where does a writer get the chance for such an internship?

You have offered us a valuable one, and I hope readers will absorb its value.

Thanks, Kathryn. I met Jim years ago at the Squaw Valley Writers Conference. I would call him the most generous curmudgeon I have ever met. No fun being on the receiving end of his scathing wit, but so incredibly giving to writers who work with him. Cara Black has been in his writing group since she first began writing the Aimée LeDuc series and cherishes his input. I love his hive mind plotting concept. Wish I’d been there.

Accepted an assignment with no idea how to accomplish it? Yes, although I knew I had plenty of material. Bushwhacked through the mess? Yes, and came out with a promising and still awkward draft, full of irrelevancies that I “just had” to include. Had good beta readers? The best, and I pruned out the distractions. Despaired over finding a decent, let alone wonderful, ending? I got up from my desk and took a walk. The ending flew into my head from wherever endings roost. Was it one of my best pieces? You bet–and well received, too.

David, congratulations on finding your way to a fine and inventive Holmes story. I look forward to reading it.

Meanwhile, “turning Moses into a surfer”? Now there’s a prompt. WU’ers?

I’m surfin’ down Mt Sinai

Two tablets in my hand

My people chaff — a Golden Calf?!

I plow into the sand

Ahem. Permit me to begin again.

Thanks, Anna. I emailed Therese about this post and confessed that I think the only advice to be gained here is, “Keep working.” She replied that this might be the only advice ever worth following. Seems like it worked for you. Congrats.

BTW: I’m a firm believer in the school of: If You’re Stuck Get Up and Move Around. I studied math in college and some of my professors had studied in Germany where you went to class all morning then took walks with your professor in the afternoon. Something about the pace of walking is conducive to thought.

BTW: if you ever get the coordinates for where endings roost, please share.

David, I loved this piece because I’m a sucker for how people think and also because it brought back happy memories of my mother reading Conan Doyle stories to us. They were terrifying, yet we asked for more.

And yes, all that work and digression for a short story but the work itself is its own reward, no? I have a tendency to jump in with a yes because I don’t think of obstacles. There’s just excitement and it’s only later in the day that I panic when I realize how much I have to do and in a short time. But it’s always turned out good. I work well under pressure. I’ve talked to others who’d hate to be on a deadline.

Congratulations on being chosen to write and thank you for sharing the experience.

Thanks, Vijaya. I’m a firm believer that deadlines are a writer’s best (most terrifying) friends. Wishing you a lovely holiday season.

David, what a bold move exposing your insecurities! Of course, as Laurie and I knew before we asked you, you need not have worried: Your story is terrific–powerful and quite original. We loved working with you! Welcome to the ranks of Sherlockians!

Color me humbled, Les. Thanks a million for inviting me aboard.

Always good to know great writers like you struggle too! I’m sure it will be wonderful.

You are WAY too kind, Deb, but thanks a million.

David – thanks for a fascinating behind-the-scenes look at an exciting challenge, and how you rose to the occasion. Looking forward to reading your Sherlockian story!

This makes two themed collections that I’m aware of your work appearing in. I’d love your thoughts about the act of writing to a prompt or theme. What’s easier about it? What’s harder?

Thanks, Keith. Actually, I’ve done a number of them: stories inspired by “Meeting Across the River” by Bruce Springsteen, stories inspired by Johnny Cash, Steely Dan, not to mention the geographically specific noir collections: San Francisco Noir, Las Vegas Noir, Phoenix Noir, and Lone Star Noir. Some are easier than other, but for the most part it’s always challenging to get an outside prompt, nudging me out of my own head and comfort zone. The hardest were the Steely Dan and Sherlock Holmes collections, because the demand for high quality was so clear-cut. But in all of those cases the prompt was mostly thematic, even atmospheric, and the challenge there became — “Where’s the story?” That was always the hardest part.

I loved this David and I’m so glad you said “yes” and that you revealed to us some of the steps you took and what you learned. Fascinating. Writing is always a journey and you often don’t know where the hell it will lead you.

Amen to that, Beth.

David, tasty stuff on your research minings, and how you transmuted that ore to gold (you did, right?) If your Moses-as-sand-surfer poem suggests, no problem with historical fiction.

Mr. Frey’s 10 Rules are perceptive. Did it take you a tremendous amount of time to get all the Holmesian backstory? I hope some of it was fun. Thanks for the post.

Thanks, Tom. Did I turn it into gold? That’s for readers to decide, not me.

I did get a wee bit bogged down in the research, as my initial draft of the story made clear — I was WAY over the word count limit. I even got into the small details of particular battles that my Irish soldier would have taken part in, and I kinda got lost in the whole saga of the Irish Transvaal Rangers who fought with the Boers. (Having just finished a lot of research about the Apache wars for my last novel, I found the whole Gen. Crook/Geronimo connection fascinating.) I also tried to make sure I didn’t fudge details about nursing at that time, especially in Africa, or the whole concentration camp saga. I had to learn about typhus and its symptoms (it killed more soliders than combat). I had to learn about Lord Kitchener and his spotty war record, etc. Then there was making sure I got details about London circa 1902 right, because that’s where most of the story takes place.

But you know what they say about research: it’s a creative form of writer’s block.

David, I love your idea for the story. I’ve read all of Conan Doyle’s Sherlock stories many times as well as Nicholas Meyer’s Sherlock novels (loved THE SEVEN-PER-CENT SOLUTION). The Valley of Fear was fascinating as you said, coming from a very different perspective of the precursor to unions.

In some ways a lot of what you bring up in the course of researching reminds me of the different ways of looking at the IRA at various points in time. In some ways it seems that every story is like that – even the villain is the hero of his or her own story, and has what they deem to be valid reasons for what they do.

I’ll be curious as to what you came up with for Moriarty.

Thanks for sharing your process on this – great to read through it and get a sense of how you grappled with the immortal detective.

Thanks, Carol. I’ll be interested in your take on how the story turned out. And yeah, there’s a whole lot of moral ambiguity in it.

David:

How did you compress so many storylines into a short story? Sounds like reading the piece would be a crash course in writing flash fiction as well.

Well, I focused on one key storyline — how was Moriarty going to try to take down Sherlock Holmes? The rest was all ancillary to that one key driving force. It was there to supply verisimiltude and texture, not take over. I also had excellent editors in Laurie and Les, who knew when and where and why to apply the ax.

I enjoyed all the discussion of creativity while working with boundaries, but mostly I just lost a half-hour trying to re-tell the story of the Israelites leaving Egypt as a surfer epic. As Arlo Guthrie said, “That pharaoh was so rich, he didn’t even know dope had seeds in it.” Gnarly.

Which song is that? Love it.

I’m not certain. I heard it in concert, and I think the song was his rendition of someone else’s spiritual: “Oh, Mary, Don’t You Weep.” (Don’t you moan, ’cause Pharoah’s army got drownded, Oh, Mary, don’t you weep.)

As you might expect, the “seeds” line wasn’t actually in the song. Arlo used music as a frame for comedy.