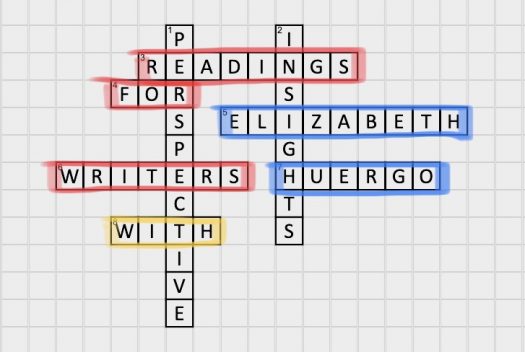

Readings for Writers: It Could Happen Here

By Elizabeth Huergo | October 27, 2020 |

These past few years Sinclair Lewis’s novel, It Can’t Happen Here, has attracted interest as an eerily prescient story about an authoritarian US president, more con artist than ideologue. Writers at Salon, Slate, and The Washington Post have certainly drawn parallels between Donald Trump and Lewis’s Senator Berzelius “Buzz” Windrip, a character based on the demagogue Huey Long. Windrip wins the 1936 presidential election, defeating Franklin Delano Roosevelt by promising the common man that he will restore a halcyon past that never actually existed. Once in office, Windrip dissolves whatever obstructs his will to power: Congress and the Judiciary; the sovereignty of states; the rights of women and minorities. In their place, he establishes what Lewis terms the “Corpo” government, a homogeneous “corporatist” regime that brooks no differences and no dissenting opinions, explicit or implied, and is administered by businessmen such as the prosperous Francis Tasbrough, who insists flatly that “it” (fascism) can’t happen in the US.

These past few years Sinclair Lewis’s novel, It Can’t Happen Here, has attracted interest as an eerily prescient story about an authoritarian US president, more con artist than ideologue. Writers at Salon, Slate, and The Washington Post have certainly drawn parallels between Donald Trump and Lewis’s Senator Berzelius “Buzz” Windrip, a character based on the demagogue Huey Long. Windrip wins the 1936 presidential election, defeating Franklin Delano Roosevelt by promising the common man that he will restore a halcyon past that never actually existed. Once in office, Windrip dissolves whatever obstructs his will to power: Congress and the Judiciary; the sovereignty of states; the rights of women and minorities. In their place, he establishes what Lewis terms the “Corpo” government, a homogeneous “corporatist” regime that brooks no differences and no dissenting opinions, explicit or implied, and is administered by businessmen such as the prosperous Francis Tasbrough, who insists flatly that “it” (fascism) can’t happen in the US.

Of course, Lewis knew better. For one thing, he was married to Dorothy Thompson, the renowned journalist and radio broadcaster who reported from Germany and other parts of Europe about the rise of the Nazi party. Her reportage and her experience as the first US journalist expelled by Hitler informed Lewis’ story of how easily a democracy can slip into a dictatorship, a “Corpo” government. For another, though he was neither a conscious stylist nor a meticulous plotter, Lewis was drawn to the problem of a society that values material wealth over all else. Indeed, this was his grand theme, an idea that runs through so much of his work and may be the very reason why H.L. Mencken considered him such an “authentic” writer.

Lewis describes Buzz Windrip as a “corporatist,” his government as “Corpo”. In the novel, the corporation works in direct opposition to democracy and its values, represented by Doremus Jessup, the Vermont newspaper editor “locally considered ‘a pretty smart fella but kind of a cynic’”. The problem, however, is that Doremus the Dormouse has stayed in hibernation too long. His retreat symbolizes our collective retreat from civic engagement, the commonweal. Lewis was criticized by his contemporaries for not offering clear political solutions through his novel. I think he did, though. The “corporatist” state that values material wealth and power above all else is a harbinger of authoritarianism, a shift in values that transforms the world and everything in it into a series of transactions meant to satisfy the interests of Windrip.

The archaeology of the word “corporation” reveals something of that difficult answer Lewis sought to convey. The earliest example offered by The Oxford English Dictionary is from Thomas More’s 1534 Treatise on the Passion, (written while More was sitting in the Tower of London, the object of the king’s disdain):

“He [Christ] doth…incorporate all christen folke and hys owne bodye together in one corporacyon mistical.”

In this early use of the word, Christians join together in the corpus, the body of Christ, which is a mystical space, one that offers unity and solace.

For us and for Lewis, the more recognizable definition of “corporation,” drawing again on The Oxford English Dictionary, is “a body corporate legally authorized to act as a single individual; an artificial person created by royal charter, prescription, or act of the legislature, and having authority to preserve certain rights in perpetual succession.” This is a legal, a transactional space that ensures certain rights over property. It offers ownership in perpetuity.

Lewis’ religious faith changed at points in his life, sometimes believing, sometimes not at all. So, I am not suggesting that he offered a religious answer to the problems of a secular democracy. When the Minute Men (an armed militia) burns Doremus’ beloved 34-volume illustrated edition of Dickens, books lovingly passed down to him by his father, Doremus cannot look away. He can only accept the spectacle passively: “It was like seeing for the last time the face of a dead friend.”

Authoritarianism depends on collective passivity. Lewis’s characters hesitate to talk about difficult subjects, to put aside their differences in order to advance the common good, and that makes them vulnerable to the buzz of a political wind that rips through them. Authoritarianism depends as well on a type of education that draws on the virtues of the “corporatist” state–speed, superficiality, a strictly transactional short-term pragmatism. Indeed, under Windrip’s government, “students were encouraged to read, speak, and try to write modern languages, but they were not to waste their time on the so-called ‘literature’; reprints from recent newspapers were used instead of antiquated fiction and sentimental poetry. As regards English, some study of literature was permitted, to supply quotations for political speeches, but the chief choruses were in advertising, party journalism, and business correspondence, and no authors before 1800 might be mentioned, except Shakespeare and Milton.”

A secular democracy depends first on an educated citizenry that can understand complex ideas and distinguish between fact and fallacy. Eventually, Doremus the Dormouse learns to roar like a lion. He joins the liberal resistance. He writes editorials for The Vermont Vigilance. And vigilance is the second necessary element required to maintain a balance between individual and collective rights.

The collapse into an authoritarian government could happen here, just ask any of us who come from other parts of the world where a foreign government, often the US, has intervened in national elections and suppressed the vote or just downright ignored the will of the people. For anyone with a dark sense of humor, or even just a mild predilection for irony, Lewis’ work is worth the time and effort. There’s a good reason why he was the first US writer awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature.

Do you have a favorite political satire?

[coffee]

I’ve always had a soft spot for Jonathan Swift’s A Modest Proposal. I first read it in high school, and was more amused than sobered. Reading it later, though, having lived some life, was like getting a smack to the back of the head. I came up in the 60’s and early 70’s and did my share of marching, rejecting, and quoting Eisenhower to my father about the dangers of the military-industrial complex and the collective passivity of his generation. Cruelty, injustice, creeping tyranny, a transactional way of life. It’s been like watching black mold v creep up a wall. Here’s the woo-woo part for me this morning. I keep a little box near my desk that I think belonged to my late father-in-law. I unearthed it a couple of years ago and in it, I discovered two Eisenhower stamps and a 14-cent Sinclair Lewis. I keep them close as reminders that while I strive to entertain my readers, it’s also my job to layer in deeper meaning. Among the many things you said in this post, two things will stay with me. “…just ask any of us who come from other parts of the word…”, and the paragraph that begins with “A secular democracy depends first on an educated citizenry…” Thank you, Elizabeth.

Thank you, Elizabeth. Too many in the U.S.A. have never been out of the country, and lack perspective. They can’t imagine anything other than the brand we have made for ourselves. That branding is being unmasked, and about 40% of the electorate resent it. Thank you again.

Hi, Elizabeth:

I’ve often wondered why It Can’t Happen Here is considered satire. It feels much more like a cautionary tale. And, as it’s main character is based on Huey “Kingfish” Long, it bears a sibling resemblance to Robert Penn Warren’s All the King’s Men.

The latter also makes a point of including the press not as champion of the people but a willing dupe in the rise of the populist strongman. A similar theme animates the 1941 Frank Capra film Meet John Doe, which, like Lewis’s work, shows a businesman exploiting the frustrations of working people — with the help of a private militia — trying to take power. It remains one of my favorite films, and feels as eerily prescient as It Can’t Happen Here.

Thanks for the timely post. I’m currently working with a group planning for post-election rallies across the country to ensure all legitimate ballots are counted. Just last night the Supreme Court ruled that mail-in ballots rightly cast by election day in Wisconsin cannot be counted after election day. It can happen here. It is happening. And as Lewis rightly emphasized, the only thing that can stop it is citizen engagement.

Thanks, Elizabeth, for the deep-dive. I’ve read Lewis, but never It Can’t Happen Here. Eerily prescient.

Your etymology of ‘corporate’ reminded me of the 1983 song, The Walls Came Down, by Michael Been and his band, The Call.

Well they blew the horns

And the walls came down

They’d all been warned

And the walls came down

They stood there laughing

They’re not laughing anymore

The walls came down

Sanctuary fades, congregation splits

Nightly military raids, the congregation splits

It’s a song of assassins, ringin’ in your ears

We got terrorists thinking, playing on fears

Oh Well they blew the horns

And the walls came down

They’d all been warned

But the walls came down

I don’t think there are any Russians

And there ain’t no Yanks

Just corporate criminals

Playin’ with tanks

It makes me think that through the Cold War (most of my life), the corporate criminals held us in thrall via fear of this vast “other” in the Soviet bloc. With the collapse of the USSR, keeping us in thrall necessarily had to grow more overt: fear of socialism, fear of lost privilege (made a zero-sum equation—anything ‘they’ gain is your loss). Culminating in an honest-to-God and stunning fear of actual democracy! By a stunningly large minority.

Oh, how the sanctuary has faded. And wow, how the congregation has split. Guess Micheal Been was prescient, too. Terrifying, but also a reminder how vital our calling is, and how much more so it becomes. Just as Doremus was, we are called to roar. Thanks for “the call” to deep thought.

I loved that song Vaughn, and it does its dark, storming-the-gates tone does have resonance today. That band originated in Santa Cruz and played around here a lot.

And I second Mr. Corbett’s recommendation on “Meet John Doe,” which also has unsettling current parallels.

Democracy has been called an experiment more than once, and today’s laboratory is overrun by black mold, viruses and other Orange Despot pathogens. Vote for decency and the better angels of our nature.

That should be “its dark…” above. And Elizabeth, I didn’t thank you for the persuasion of your post. Thanks!

Thank you so much for this. Will read Lewis’ classic book!

“An artificial person” – that should have warned us right there! You know what they say, “I’ll believe corporations are people when Texas executes one.”

My dad gave me Animal Farm to read when I was about twelve. Unfortunately he didn’t warn me what kind of story it was, so little twelve year old me didn’t have a very happy time reading it. It was more interesting a few years later when I’d got a bit of high school Soviet history under my belt, though still not exactly Fun Times.