Black Comedy–A Genre for the Moment?

By David Corbett | October 9, 2020 |

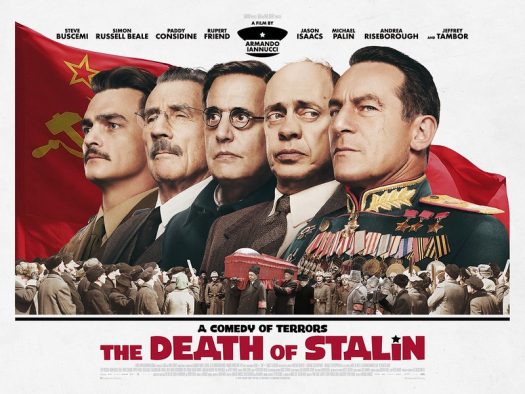

Death of Stalin poster by mwmbwls

Given recent political events, the film The Death of Stalin has been very much in the public mind. It’s a particularly brilliant black comedy, courtesy of Armando Ianucci, who is also responsible for other ingenious, politically-premised black comedies such as the film In the Loop and the TV series Veep and The Thick of It, as well as the sci-fi-inflected Avenue 5, which takes on the imaginable absurdities of luxury-liner space travel (should such a ghastly thing ever come to pass).

It may be that current events—characterized by an overwhelming sense that something fundamental has gone very wrong, with blame often placed on failing institutions—make black comedy a particularly apt genre for the moment. But what is it, exactly?

It’s been my experience that black comedy is a genre often defined more by “I know it when I see it” than any reliable set of conventions or guidelines. And yet I find that what most people think of as black comedy is anything that is darkly comic—including farce and satire as well as much of noir and hard-boiled crime that possesses a tinge of black humor—which is woefully imprecise, especially for writers.

For example, though the Catholic Herald deemed John Michael McDonagh’s Calvary a “jet black comedy,” I think the following discussion will reveal it’s not at all. (I will return to it below.) Rather, it’s a poignant drama laced with bleak Irish wit.

Genres serve a purpose. They establish certain conventions the writer and reader/audience both recognize as the rules of the highway—with the understanding that often the best part of the journey happens off-road. And some byways, existing in a no man’s land claimed by two or more genres, often provide the most surprising jaunts of all.

That said, I thought I’d use this month’s post to try to clear up some of the definitional confusion surrounding black comedy, since it may well be that it becomes a genre of not just current but continuing appeal, and some of us may want to try our hand at it. (I’m doing so in my current WIP, for example, depicting a dystopian future in terms of the oppressive systems that survived the great crisis.) If so, it’s best we learn a few of the aforementioned rules of the road.

A good working definition of the genre can be found in John Truby’s The Anatomy of Story.

For Truby, comedy concerns patently absurd, pathological, even deadly systems, organizations, or cultures, and portrays individuals invested in those entities struggling to succeed within them, to disastrous effect.

Note that there is no obligation for the black comedy to be funny. For example, Goodfellas isn’t explicitly comic, but its structure adheres perfectly to Truby’s format (as do many of Scorsese’s films, such as Mean Streets, Casino and The Wolf of Wall Street).

Black comedy concerns patently absurd, pathological, even deadly systems, organizations, or cultures, and portrays individuals invested in those entities struggling to succeed within them, to disastrous effect.

Black comedy differs from satire in that with satire, though the individuals may struggle to succeed in the misguided system or culture—think the rigid class structures in Austen and Wilde—there is usually a climactic moment of self-conscious insight into the absurdity of the overall situation, resulting in the newly aware character abandoning the system/culture or finding a way to live authentically within it, often because of a romantic connection or some other meaningful relationship.

In black comedy, many if not all of the individuals pursuing success within the destructive system remain blind to the futile, insane, even fatal consequences of the quest. The characters generally do not enjoy a climactic moment of enlightened discovery (or shock of horror); that is left for the audience.

For example, in The Death of Stalin, the pathological system is the dying dictator’s totalitarian USSR, and the characters relentlessly pursue their murderous ambitions to take his place. No one suddenly reflects and thinks, “This is madness.” They just all go mad.

Other examples:

Dr. Strangelove: With the lone exception of a British captain (Peter Sellars) who proves unsuccessful in getting General Jack Ripper (Sterling Hayden) to call off his unprovoked nuclear attack, everyone seeks to maximize their chances of victory in a cataclysmic war—or survival in its apocalyptic aftermath—doing so in an atmosphere of mutual paranoia and jingoist triumphalism, while in thrall to a strategy of deterrence with the acronym “MAD”—Mutually Assured Destruction.)

Wag the Dog: In this film, based on Larry Beinhart‘s 1993 novel American Hero, the insane system marries the cynical manipulations of politics with Hollywood’s genius for creating false but credible realities. The president is caught with an underage girl. With re-election in the balance, the scandal threatens to destroy his presidency. Enter Conrad Brean (Robert DeNiro), spin doctor par excellence, who decides to invent a war to distract the public, and brings in Hollywood producer Stanley Motss (Dustin Hoffman) to work his magic. When the CIA, secretly in league with the president’s opponent, pushes back against the false narrative, Brean and Motss get increasingly, even outlandishly inventive, with amazing success. When the president’s poll numbers take a turn for the better, however, it’s attributed to his lame campaign slogan (“Don’t change horses mid-stream”), and Motss becomes outraged that his brilliance isn’t being recognized. He wants to take credit for the disinformation campaign, even as Brean warns him he’s “playing with his life.” Motss declares he’s going forward anyway, and Brean has his security team kill him, while telling the press he died peacefully in his bed at home.

As those two examples make clear, there are typically few if any redeeming characters in a black comedy, because they are all invested in the destructive machine. However, if this threatens to make the story too bleak for audiences, writers sometimes employ a kind of Sancho Panza character who serves as a stand-in for the audience, refusing to join the general madness, and watches from a distance as the others dive into the flames. (The William Holden character in Paddy Chayefsky’s Network is an example.)

There are typically few if any redeeming characters in a black comedy, because they are all invested in the destructive machine.[But] writers sometimes employ a kind of Sancho Panza character who serves as a stand-in for the audience.

There is nothing requiring the writer to restrict himself to the misbegotten; sympathetic characters are not forbidden. Any hopes they may harbor concerning overcoming the machine, however, seldom reach fruition.

In Terry Gilliam’s 1985 film Brazil, a minor bureaucrat named Sam Lowry (Jonathan Pryce) isn’t so much invested in the system as too timid and lazy to oppose it. He toils away meaninglessly in an agency of the increasingly authoritarian government during an insurgent bombing campaign, which was modeled on the Provisional IRA’s attacks in London during the early 1980s. In the course of the story, he encounters two individuals who are actively opposed to the system—a subversive handyman named Harry Tuttle (Robert DeNiro) and a revolutionary truck driver named Jill Layton (Kim Greist), with whom Sam becomes smitten. Despite his fascination with Tuttle and his romantic attraction to Jill, he never commits himself to join the struggle, but instead tries to his best not to make waves. Despite that timid hope, he is targeted for surveillance anyway, his contacts with Tuttle and Jill observed, and he’s arrested, imprisoned, and tortured to death by his own cousin (Michael Palin), a secret operative in the security services.

Each of these stories could be rendered as straightforward drama, even tragedy, if the focus were lest on the destructive order and more on the protagonist—or if that protagonist were more self-aware, more sympathetic, or less invested in the system.

Returning to the example used at the top, John Michael McDonagh’s Calvary, it concerns a widower-turned-priest (Brendan Gleeson) in a small Irish town trying his best to serve the spiritual needs of his cynical, dysfunctional, self-destructive parishioners. He does this in the face of not just lacerating insults and taunts but a death threat in the confessional giving him three days to live. Though innocent, he must die to pay for the church’s legacy of child abuse, as Christ died for mankind’s sins. Bleak humor leavens the drama, but Fr James is far too sympathetic, and his death too poignant (if, in the end, pointless), to fit neatly into the black comedy canon. And where is the destructive system? Catholicism plays no larger a part than small- town Irish provincialism or modern cynicism in shaping the bitter world the characters inhabit.

In the same vein, what differentiates many noir stories from black comedies isn’t the thematic set-up, but the focus. For example, if you wanted to stage Dog Day Afternoon as a black comedy, you wouldn’t make Sonny (Al Pacino) so sympathetic, and you wouldn’t have him robbing the bank to get the money for his lover’s sex change. You would have him working inside the bank, using the corrosive greed animating its procedures to his own advantage, while competing with others invested in the system to claw his way to the real money.

If what you’re hoping to portray is how so many get caught up in the intoxicating madness of a destructive system, organization, culture—even a dysfunctional family—black comedy is worth your attention. It may provide you the structure you need to pull the thing off without getting lost in scattered incidents of madness.

But if you want to poignantly portray the damage done, you’ll need a sympathetic Sancho Panza character—or a completely different approach, focusing on the struggling individuals, not the system designed to crush them.

What black comedies, if any, have appealed to you? Why?

Have you ever considered trying your hand at one? How did it turn out?

Do you prefer to focus on the individual characters’ struggles, rather than the system, structure, organization, or culture in which they’re trapped?

“Gentlemen, You Can’t Fight In Here! This is The War Room!” Dr. Strangelove is a personal favorite.

David, have you ever looked up the lyrics to the M.A.S.H. theme song? That was an eye-opener for me, but the most memorable example of black comedy that I’ve experienced is one infamous cover for National Lampoon Magazine. It’s a photograph of a gun pointed at a dog’s head with the tagline ‘If you don’t buy this magazine, we’ll kill this dog.’ A rather bleak take on our attention-grabbing culture. In books, I’d add the Christopher Buckley novel Thank You For Smoking, the story of an unethical tobacco industry spokesman.

What I think makes black comedy effective is exorcising irrationality. Something that is widely believed but not widely considered.

Oh, I like that, James. Thanks for the addition.

Hi, James:

I think Strangelove is my archetypal black comedy. The story behind how it got made is as fascinating as the film itself. Kubrick began working on it as a straight-ahead drama, but during late-night brainstorming sessions with his co-writer, they started laughing and couldn’t stop, and realized that a comedic approach was the way to go. That prompted the decision to bring Terry Southern (Candy, The Magic Christian) aboard to goose up the script. He was the one to come up with the opening of the B-52 and KC-135 Stratotanker “copulating” during refueling while “Try a Little Tenderness” plays in the background, as well as character names such as Gen. Jack Ripper, Gen. Buck Turgidson, President Merkin Muffley, etc.

Unfortunately, a straight movie about the same subject was in production at the same time: Fail-Safe, with Henry Fonda. Kubrick knew if the funny version came out after the straight one, it would bomb. So they sued Columbia — the production company for BOTH films — over a bogus copyright claim, just to slow down Fail-Safe enough so Strangelove could come out first.

As for exorcising the irrationality–yes, for the reader/audience. Sadly, not so the characters.

One of the reasons so many black comedies are indeed comic is to soften the blow of the darkness a bit. Scorsese’s films use humor (and humanizing the characters) in that same way, to lighten the drakness as it were, but not in the stylized manner of Strangelove, Wag the Dog, or Brazil. As a result his films have the feel of straightforward dramas, even though they deal with destructive systems–organized crime, Wall Street.

Thanks for the post and the reply.

David, thanks for this post, which really got me thinking this morning. Mostly because I realized that I’m writing a dark comedy.

Yup. I’m writing about the dark secrets kept by a dysfunctional community, and how those secrets have impacted two people in particular (though, really, they’ve impacted them all). And guess what my challenge has been? The structure. Or at least the structure for the unspooling of all of those secrets. (Subtext: This book is trying to kill me.)

I’ve been meaning to watch The Death of Stalin for a while now. My son, who graduated from film school this past spring, recommended it, and is now — coincidentally — working for “The Wolf of Wall Street” himself. Our better instincts have kept us from watching that film, but I see now that I have a new reason: homework.

Thanks again for this.

Hi, Therese:

I didn’t get into structure much, as the post was already somewhat long, but black comedy often has the feel of one long escalation–one damn thing after another, ending in doom. The problem is, that can seem repetitive unless the stakes truly do escalate. Things to keep in mind:

1. Competition: make sure at least two characters are trying to be top dog in the destructive system. And since its ethos is pathological, they will gradually move toward pulling out all stops in order to win. And those increasingly diabolical actions should be rooted in the ethos of the system, i.e., they are doing exactly what the system/culture would expect of them. But in terms of structure, the competition gives you a tit-for-tat strategy for amplifying the stakes; the loser of one scene/sequence ups the ante in order to prevail in the next, then vice versa.

2. A moment of hope: As Don told us recently, the ending is created in the middle of the story, and to create a truly devastating ending, you have to create hope that the madness can be dispelled. In Strangelove, that’s the moment when the War Room cheers as they see their own planes (carrying nuclear weapons) getting shot down! It doesn’t last, of course. One gets through, flown by USAF Maj. “King” Kong.

3. The “rational” character: to provide tension and counterpoint, you typically need a “rational” character who sees through the madness and who makes at least an attempt to stop it. Without such a character, very often the full effect of the madness/pathology/destructiveness cannot be felt because all the other characters are not sympathetic. In The Death of Stalin, this character is Stalin’s daughter, who despises the conspirators (who in return plan to kill her). In Catch-22, it’s actually the protagonist, John Yossarian. This is rare, but it shows you that the format isn’t a straightjacket any more than any other genre is. It has conventions, but they are guidelines, not inviolable laws.

I hope that helps, at least a little.

It does help, in most because I see I’ve been on the right track. Thank you, David!

Such an interesting post–I don’t think I have a black comedy in me; heck, I can’t even do real comedy, only inadvertently. But recently I watched Canadian Bacon and it was so funny, but also pointed to some truths. Premise is to start a Cold War with Canada to jack up ratings for the US Pres. John Candy and Rhea Perlmann are hilarious.

David, I think you’re a fan of Shawn Coyne’s work, yes? Then would this be accurate? Black comedy is essentially a man-versus-society construct with an internal content genre which deals with status. And it must not include a worldview or morality internal content genre except where a minor character is allowed to change for the better so as to act as a foil to the unreedemed.

If this sounds like gobbledegook, don’t bother to decipher! If not, here’s a page for reference to the terms I’m using: https://storygrid.com/internal-genres-part-1/

To answer your question, it’s not a favorite genre of mine. I prefer smaller casts than black comedy generally provides. I also prefer stories that end on a hopeful note.

Hi, Jan:

Yeah, my vote is that definition is a lot of words trying to sound more intelligent than they are. I’m often accused of being overly academic, but I can’t hold a candle to that.

Your resistance to black comedy is understandable. It is not for everyone. But when done well, I’ve felt it as a welcome if not necessary shock to the system.

Hello David.

Your two working examples relate to past events, and that makes them more safe. True, Dr. S has not only remained relevant since the end of the cold war, but has taken on heightened meaning in the Age of Trump. Ditto for Stalin. But what I see is lots of nihilism (Veep for laughs, House of Cards for laugh-free futility). As for black comedy, these days, that’s called Breaking News. What is coming out of Washington or, say, the pathetic “patriotic” displays at the state capital here in Michigan that isn’t black comedy? The idea of adding another layer to it in the form of fiction is not tenable–again, for me.

It would seem to me that finding a comedic path that isn’t black makes more sense. I’m getting plenty of black humor from, say, The Lincoln Project. What I would be grateful for is funny writing that isn’t frivolous, that leads to thought. It’s hard to do, but that’s one of the better reasons for trying to do it. I stick by one of Clive James’ best maxims: “humor is common sense, dancing.”

Thanks for the comment, Barry.

I have a friend who worked in politics for years and he said Veep was the most authentic look at those in government he’d ever seen.

There is another black comedy called Four Lions concerning terrorism–very tricky. We’ve not seen many black comedies about the war on terror other than that and Brazil (which did not do well at the box office — too soon), though In the Loop used the war on terror as a pretext for the US obsession with going to war in Iraq.

And I think a black comedy about the Wolverine Watchmen is long overdue.

Another film I forgot about that is current, especially in light of today’s hearing before the Judiciary Committee, is Citizen Ruth, about the abortion “debate.”

So I don’t believe my choice of examples in any way indicates that the form has lost relevance. Indeed, my entire premise was that the truth is quite the opposite.

We live in absurd, deadly times. Depicting the insanity of that in an approach that underscores the investment of so many in the murderous madness seems pitch-perfect for those so inclined. For those not so inclined, there is a buffet of other options.