Do it Again, Do it Again

By Dave King | March 17, 2020 |

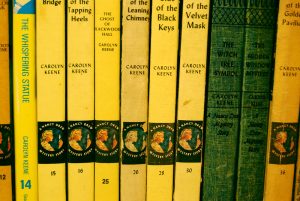

When I first started reading books more complex than Green Eggs and Ham, I fell in love with series novels. I raced through the school library’s collection of The Hardy Boys and Nancy Drew. A friend loaned me the complete John Carter of Mars series – great fun when you’re twelve, though they don’t hold up very well – and another introduced me to the Chronicles of Narnia. I even went through my sisters’ old Bobbsey Twins books, which can be taken as a sign of how little reading material we had in the house.

When I first started reading books more complex than Green Eggs and Ham, I fell in love with series novels. I raced through the school library’s collection of The Hardy Boys and Nancy Drew. A friend loaned me the complete John Carter of Mars series – great fun when you’re twelve, though they don’t hold up very well – and another introduced me to the Chronicles of Narnia. I even went through my sisters’ old Bobbsey Twins books, which can be taken as a sign of how little reading material we had in the house.

What drew me to series was the comfort of going back to a familiar world, one that was already alive in my imagination. I looked forward to spending time with characters I’d already come to know and love. Besides, even if you’re a voracious reader, it’s a commitment to read an entire novel, especially if you can’t bring yourself to abandon a book you’ve already started. (I’ve mentioned before — it’s down in the comments — that I regret not being able to give up on Kurt Vonnegut’s Breakfast of Champions.) It was easier to commit to the next book in the series because I knew what I was getting into.

Now that I’m a grown-up editor, I can see why series also appeal to writers. It’s tough to write any novel without falling in love with your characters, and once these people are alive in your imagination, you want to keep following their stories. Besides, you can’t always really explore your characters in the space of one novel. There’s also the practical fact that agents and acquisitions editors like the way series novels offer upside protection. If your first novel hits big, your editor knows you have others in the pipeline.

But series books raise some questions that standalone novels don’t. For instance, how do you keep your characters consistent as they age? It’s part of J. K. Rowling’s genius that Harry and the Hogworts gang age plausibly throughout the series. As they mature, their relationships grow more complex, their internal struggles are more gripping, and readers are drawn deeper into the series.

But this kind of growth isn’t always possible, which is why some writers to simply freeze their characters in time.

Throughout the 41-year run of their novels, Nero Wolfe remained 59 and Archie stayed 35. Archie never quite gets together with Lilly Rowan, Saul Panzer never advances beyond a hired operative, and Cramer remains perpetually annoyed. This frozen timescape sometimes required some fudging. Paul Whipple, a college student who appeared in 1938’s Too Many Cooks, shows up again as an adult in 1964’s A Right to Die, looking for help for his grown son. He’s 26 years older. Wolfe and Archie haven’t aged a day.

Still, even within the ageless framework, characters can’t help but grow – slowly deepening your characters is one reason to stick with a series. Over the course of the Wolfe books, Wolfe becomes less loquacious (he was very prone to speeches in the early books) and more respectful of Archie. Cramer may remain annoyed, but a mutual respect builds between him and Wolfe as well, especially after Cramer winds up on Wolfe’s side on a couple of cases. And [spoiler alert] Orrie Cather, one of Wolfe’s periodic assistants, slowly grows more self-aggrandizing and amoral until, in A Family Affair, the final Wolfe novel, he turns out to be the killer and commits suicide on the stoop of the brownstone.

Letting your characters to age naturally has its risks, as well. In 1930’s Murder at the Vicarage, Miss Marple is already fairly advanced in years. By 1971’s Nemesis, she is fantastically old. When Patrick O’Brien started the Aubrey/Maturin series, set during the Napoleonic wars, he placed the first book, Master and Commander, in 1800 and allowed the chronology to develop naturally. But by the sixth book, Fortune of War, set in June, 1813, he realized he was going to run out of Napoleonic War before he ran out of Aubrey/Maturin stories. So several years pass in the world of the novels, including a long tour in the Pacific, until in the 18th book, The Yellow Admiral, readers find they are in November, 1813.

The greatest danger of writing a series is that your fans and publisher may demand that you keep bringing back popular characters after you’ve lost interest in them. A number of great writers have ruined beloved characters by pushing them long past their natural shelf life. Mark Twain clearly loved Tom Sawyer and Huck Finn in the earlier novels, but when he resurrected them because he needed the money, the results – Tom Sawyer Abroad, and Tom Sawyer, Detective, were so awful some reviewers thought they were intended as parodies. By Mostly Harmless, the fifth installment of The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, it was clear that Douglas Adams had become bored with Arthur Dent and was simply looking for a way to kill him off. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle did kill off Sherlock Holmes, but fans forced Doyle to bring him back.

Then there’s Agatha Christie’s troubled relationship with Hercule Poirot, whom she once referred to as “a detestable, bombastic, ego-centric little creep.” Yet from his first appearance in 1920 in The Mysterious Affair at Styles, Poirot was immensely popular, so Ms. Christie felt obligated to keep churning out Poirot books. She vented some of her feelings in 1945 in Curtain, in which she had Poirot murder someone, then commit suicide. She didn’t publish the book at the time, but she made it part of her will that it would be published posthumously, as a final act of revenge against the ego-centric little creep.

You can see this animosity in a lot of the Poirot books. The novels that most Christie fans consider her weakest – The Big Four, The Mystery of the Blue Train, The Third Girl – are Poirots. Of course, Ms. Christie was a brilliant storyteller, so some of her most successful mysteries are also Poirots. But even with those, particularly the later ones, you get the impression they succeeded despite Poirot rather than because of him.

So if you have the urge to keep following your characters because you love them and want to see what they become, then commit to a series of books. But as Ms. Christie said in her essay, “How I came to dislike Hercule Poirot,” “I would give one piece of advice to young detective writers: be very careful what central character you create – you may have him with you for a very long time!”

So what attracts you to series novels? What attracts you to them? What do the offer that standalone novels don’t?

[coffee]

One of the things that fascinates me about the Harry Potter series is that very believable aging of the characters. As a series writer, I’m dealing with that issue now. In outlining the action going forward through four books, I’m seeing my characters’ emotional arcs become more and more intertwined with the arc of the story as their changing inner desires smash into the events of the plot. I was even planning to re-read HP to observe how Rowling does this, which may be a wonderful way to spend the days and weeks of quarantine ahead. Thank you as always for an enlightening post!

When I read through the Harry Potters as they were written, I envied that group of children who matched Harry and the gang in age. They got to literally grow up with Harry Potter.

It is one thing to understand who your characters are. It’s another to understand from the beginning whom they could become, and to lay in the groundwork for their future personalities. As I say, it’s part of Rowling’s genius that she was able to do this.

Good luck with your own writing. And remember, if you have any questions on your own writing, feel free to submit them here. There may be a column about them in the future.

Thank you, Dave.

I remember going to watch the latest Harry Potter movie, (maybe #5) only just out, in the daytime, in a cinema over the road from my local university. It was packed with students, and from the moment it started there were laughs and various mutterings — “Oh, typical Hermione,” etc — the kind of comment that people make when they’re watching a video of them and their friends. That’s when I realized how very much the audience —the generation— identified with the Happy Potter characters, having grown up with them. It was an eye-opener.

Yes, precisely. When your characters take on that kind of life in your readers’ imaginations, you know you’re doing it right.

1. Haha, I read allllll the Hardy Boys, Nancy Drew, and Bobbsey Twins in our church library, starting when I was about 8. And even at 9 years old, I was rolling my eyes at the Bobbsey Twins… but still read them.

2. I never knew Agatha Christie hated H. Poirot so much. I freely admit, though, he was never the most likable of characters.

3. This is great food for thought, as I’m working on a series.

I aged out of the Hardy Boys/Nancy Drews pretty quickly, as well. But apparently a lot of kids get their introduction to reading through them.

Good luck with your series. And, by the way, if you have any questions, feel free to ask them here. Even some time later, I’ll get an alert, and I’m always happy to answer them.

Trust in the author is what draws me into a series.

I read a lot of the first books in scifi and fantasy series to see if there’s enough interesting stuff going on for me to make the commitment. I might finish that first book and decide I’m not interested enough to keep going. I might put the book at the bottom of my TBR stack after reading a few chapters since I might try it again.

But if I have trust in the author, I’ll keep going even if I don’t like the first book in the series. Which happened with The Collapsing Empire the first book in John Scalzi’s Interdependency series. Now I can’t wait for the third book The Last Emperox to come out.

I almost got into a phenomenon that is more common with science fiction writers than other genres — the shared world. I certainly got sucked into Larry Niven’s Known Space series when I was in my twenties.

There, you don’t have many shared characters (although I always figured Beowulf Shaeffer was related to Louis Wu somehow) but the books share a history and a physics/metaphysics. There you really do have to trust in the author, since he or she is the common link between the books.

Seconded on Niven.

Thanks for the post.

I’ve read series since childhood, including the much-maligned Bobbsey Twins, for whom I still carry affection. When I finished reading a beloved book and couldn’t bear leaving that world. When I finished Black Beauty for the sixth time, my mother wrenched it from my hands and handed me Little Women. I love the Louise Penney Armand Gamache series. There are fifteen now. He ages very slowly. He is also a nice man, totally counter to most wounded, quirky detectives. Yet there is plenty of conflict in each book.

I’ve forgotten nearly everything about the Bobbsey Twins books — their forgettability is one of their problems. Though I still do remember bits of the Nancy Drew mysteries. And I, too, read beloved books over and over — it’s one of the things that led me into editing. I hadn’t seen the connection between that urge and the unwillingness to leave a familiar world.

By the way, another of the few books in the home where I grew up was Pilgrim’s Progress — a woodcut-illustrated nineteenth-century presentation edition. I think I read it twice before I was twelve.

Thinking about it today, I am a serial series reader. I think my first series was Trixie Belden when I was about nine or ten, and it totally was because of the characters. I think I can even name and give the defining characteristics of most of them, still. I’m totally in awe of Susan Wittig Albert’s craftsmanship with evolving and aging characters in the China Bayles’ mysteries. I guess she wrote for the Nancy Drew series way back when, so maybe it’s not so surprising that she is so good at it.

My first two books were book one and two of a series, and it was hard to find any guidance on how to handle some of the questions you mention here, but also such concerns like how to address orienting readers back into the world (or orienting first time readers who pick up the second book first), but without overkill on backstory. I ended up using book 2 of several series to help give some guidelines. Who knows how good a job I did, as I haven’t tried to publish it anywhere, yet. But, since my current wip is the first of another series, I find myself thinking ahead to the second book and wondering if I got it right the first time.

Guidance on how to introduce your readers to a new book in the series? That is a big — and fascinating — question.

Let me think about that a bit. I may be able to come up with something.

You are so awesome! :D

I think this is a big issue! I read a lot of series mysteries; some are better than others at this. I think Rowling does a particularly good job of this, even though she surely could have counted on readers having read the earlier books.

Another author who does a good job is Margaret Maron. I’ve been reading her Deborah Knott series in order and she seems to bring in background information from earlier books just at the moment it’s needed.

So, I’m thinking the best plan is to follow the way we handle any backstory.

It’s true. Any standalone book has as much backstory as the twelfth installment of a series. The main difference is that in the standalone, readers don’t get to read it for themselves.

My older sister introduced me to The Black Stallion series when I was about ten years old. The age of Alec Ramsey, the protagonist, was never made clear (although the Black sired at least one generation of offspring). Except for a brief fling at romance (unfulfilled), his character remained uniformly decent and responsible. Looking back, I wonder if that was a conscience decision by author Walter Farley to appeal to his intended audience of preteen/teenage boys. In those days, too, I think adventure (and Alec had his share of those) mattered more in YA lit than character growth and development.

I never got into the Black Stallion series myself, though this does raise an interesting question. Assuming you’re right that Alec’s character was shaped for a particular market, how do you grow a series as the market matures? I seem to remember that, in the Nancy Drews of the thirties, Nancy was more resourceful and independent than the Nancy of the fifties. And I seem to remember reading that a modern addition to the series involves her driving out to rescue her boyfriend when his car breaks down. Slightly different Nancies, depending on the social attitude toward women.

Dave, really enjoyed this post on series. As a child, I loved all the books by Enid Blyton that I could get my hands on–from her animal books to school stories to adventure books. I think the last complete series I read were the HP books. As the books got darker (after the 3rd book) my attraction diminished. Still, l wanted to know what happened, so the plot kept me reading.

But now, it’s very rare for me to read series books. I think it comes down to the fact that I enjoy the novelty of new characters and settings, etc. I no longer ache for the familiar like I did as a child.

There is an argument to be made for standalone books, too, both for readers and writers. You enjoy the novelty of a completely new fictional world. And even the best series writers took an occasional break for a standalone.

My favorite thing about Steven Brust’s Vlad Taltos series is the world building. Throughout the series he builds complex relationships between several species that could not be developed in a single novel.

I’m also currently reading a fantasy series titled The Memoirs of Lady Trent, by Marie Brennan. Brennan builds a minor subplot from the first novel into a major obstacle in the fourth and fifth books. This adds to the significance of the character in that world.

That’s it. That kind of in-dept world building and complex plotting is what series do best. Following a single plot thorough several different books is also a pleasure that standalone books do not offer.

As a reader of mystery series’, and now a series writer, I enjoyed your post. I am quite a fussy reader. so when I find a book with characters and a writing style that I like, I feel confident investing in a book by the same author because I know it will feature the same characters and writing style. That’s why I like series.

When I planned my own mystery series, I borrowed many elements from series I enjoyed as a reader. I liked Martha Grimes’ pub names, and chose to expand on that by using highway names that also reflected the settings of each of the novels in my series. I loved Elizabeth George’s series until Lynley married Helen — I prefer the solitary, introspective type — so I chose to feature a sympathetic hero who never gets involved with a serious love interest, etc.

As far as aging goes, I am disappointed that Harry Bosch has almost aged out of his job and is no longer the only protagonist in Michael Connelly’s series. I don’t think I’ll live long enough to run into a problem with aging in my own series, but just in case, the six novels (five published, one WIP) are set over 3 years so far, so my characters age only 6 months (approximately) per story. And I don’t write too fast!

Thanks for introducing this topic.

Your quite welcome. And if you should run into the problem of your main character aging out of your series, I’ve got one word: prequels.

Yesterday, Lara asked how you handle the revelation of past history in the later books of a series. Some of your readers will know the entire backstory of the series, others will be jumping into the series for the first time. How do you handle both types of reader? It’s a terrific question, and to be honest, one I should have addressed in the article.

Well, I’ve slept on it overnight, and I realized — this is simply the standard problem of backstory. Even in standalone books, your characters have a past that has shaped who they are. And you need to learn to feed your readers the necessary history without undermining your pace. This problem is no different for later novels in a series. The only difference is that readers have an opportunity to read the backstory for themselves.

So treat each novel in the series as a standalone. Give your reader the backstory they need to understand the characters and situation. And if they’re drawn into the later novel, they’re more likely to go back and read the earlier ones.

Mine was the Thieves World anthologies, I recently went back and reread a few. Dumfounded by how much they affected what I write now, forty plus years later.

I’ve read a couple of those. They were even more intriguing in that you had several writers sharing a universe. Kind of open-source cosmology.