The Incarnations: A Conversation with Shannon Kirk

By David Corbett | March 13, 2020 |

Shortly after the turn of the year, my friend and fellow novelist Shannon Kirk tweeted about how much she loved The Incarnations by Susan Barker, and how much she wished she could discuss it with someone. The novel seemed right up my alley, so I contacted Shannon and proposed we hold our discussion here at Writer Unboxed.

[Note: To learn more about Shannon and her work, visit her website.]

First, to provide everyone with a brief synopsis of the novel:

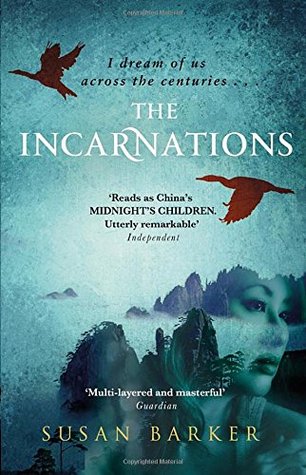

Hailed by The New York Times for its “wildly ambitious…dazzling use of language” and “mesmerizing storytelling,” The Incarnations is a “brilliant, mind-expanding, and wildly original novel” (Chris Cleave) about a Beijing taxi driver whose past incarnations over one thousand years haunt him through searing letters sent by his mysterious soulmate.

Who are you? you must be wondering. I am your soulmate, your old friend, and I have come back to this city of sixteen million in search of you.

So begins the first letter that falls into Wang’s lap as he flips down the visor in his taxi. The letters that follow are filled with the stories of Wang’s previous lives—from escaping a marriage to a spirit bride, to being a slave on the run from Genghis Khan, to living as a fisherman during the Opium Wars, and being a teenager on the Red Guard during the cultural revolution—bound to his mysterious “soulmate,” spanning one thousand years of betrayal and intrigue.

As this soulmate explains in one of the letters: To scatter beams of light on the darkness of your unknown past is my duty.… For to have lived six times, but to know only your latest incarnation, is to know only one-sixth of who you are. To be only one-sixth alive.

As the letters continue to appear seemingly out of thin air, Wang becomes convinced that someone is watching him—someone who claims to have known him for over a century. And with each letter, Wang feels the watcher growing closer and closer…

Seamlessly weaving Chinese folklore, history, literary classics, and the notion of reincarnation, this is a taut and gripping novel that reveals the cyclical nature of history as it hints that the past is never truly settled.

Next, to give everyone a sample of the writing that both Shannon and I agree makes this novel exceptional, here are a a few illuminative excerpts.

First, the opening, which daringly launches off the novel not just with a dream (a supposed no-no), but a dream within a letter:

Every night I wake from dreaming. Memory squeezing the trigger of my heart and blood surging through my veins.…I dream of the sickly Emperor Jiajing, snorting white powdery aphrodisiacs up his nostrils, and hovering over you on the four-poster bed with an erection smeared with verdigris. I dream of His Majesty urging us to “operate” on each other with surgical blades lined up in a velvet case. I dream of sixteen palace ladies gathered in the Pavilion of Melancholy Clouds, plotting the ways and means to murder one of the worst emperors ever to reign.

Next, this is Wang’s ancient soul mate discussing his current wife, Yida, in another letter—and reveals a key aspect of her own character in doing so:

I understand your need to be with your wife. Yida is a woman who stirs up in men the animal instinct to fuck and procreate. Tempting men as spoiled fruit tempts flies. But sleeping with Yida must be a sad and lonely experience, for the pleasure and the rhythm of coitus do not amount to intimacy. Your soul detaches when you conjoin with her and looks away. And I don’t blame your soul for averting its gaze. The thought of you with your wife repulses me too.…Please do not misunderstand me. You aren’t the one I am disgusted by. In other incarnations I have explored every inch of you, with tongue and fingers and eyes.…No matter how dilapidated, scarred and mutilated your body, I have always found you beautiful, for it is the soul beneath I seek.

Here is the anonymous letter-writer describing the fate and the nature of those who have been incarnated multiple times:

When I encounter one of our kind, I tally the former incarnations as a woodcutter counts rings within a tree. I date the soul as a Geiger counter dates carbon. Last week I met a shoe-shine boy in Wangfujing, who was first made flesh during the Neolithic era, when men were cave-dwellers and dragged their knuckles on the ground. When men danced around fires and had no language other than violence and grunts. The higher reincarnates, who have lived hundreds of times, tend to live as hermits far from the human fray. To meet one in the hustle and bustle of Wangfujing was rare. But there he was, beckoning me over to the wooden box where he crouched, a rag in his polish-blackened fingers. As he buffed my boots, I told him who I was and of my hopes of reunion with you.…Some of the past incarnations rise up from the depths. They crawl up the throat of the host and peer beguilingly out from behind the eyes. They manoeuvre the host’s mouth, taking over the vocal cords and tongue. “I was a Peking Opera singer, who had his feet bound at the age of six to play female roles.”

And here is how the letter-writer explains the way fate has chosen to shape her and Wang’s specific cycle of reincarnation, and how they must now defy that fate, which provides the context for her reaching out to Wang in this fashion, and points the way for the narrative arc to come:

Our souls have never met in the Otherworld. We suffer for our prolific sins against each other separately, and our paths never cross. After incarnation is when we meet. After the hand of fate has snatched up our souls and placed them in the womb to be born again, kicking and screaming into the human world. Fate throws us in the same family, the same harem, the same herd of slaves. But fate sets us against each other. Fate has us brawling, red in tooth and claw. Fate condemns us to bring about the other’s downfall. To blaze like fiery meteors as we crash into each other’s stratosphere, then incinerate to heat and dust.…The time has come to deliver this letter. For in your sixth and current incarnation, Driver Wang, we must rebel against fate. So read on. Fate must be outwitted. It must no longer stand in our way.

I’m going to let Shannon start off the discussion—what is it about this book that you find so uniquely compelling and fascinating?

SHANNON: David, first off, thank you so much for taking up the cause of The Incarnations.

I immediately fell in love with this book in 2015. Bought it out of the Barnes & Nobel on Fifth Avenue, where I was browsing, killing time, while traveling for work.

Back then, the book was on a bottom shelf, in the back of the store, and all but invisible in the sea of other books. Or, at least, this is my retrospective perception of how it was placed, given that I am of the opinion that The Incarnations should be the very first book people see when they enter a bookstore.

Better yet, it should be held aloft, like when Rafiki holds baby Simba up in glorious rays of sunlight in the Lion King, a great chorus serenading the royal offering to the grand tune of The Circle of Life.

Form & Content: Story & Style

The plot of The Incarnations immediately appealed to me: a Beijing taxi-driver starts getting letters from his soul mate, which document all of their lives together over thousands of years. Fine. Sold. But what you get is so much more.

Barker’s style is captivating, shifting you from the taxi-driver’s present-day life in Beijing to all of the soul mates’ past lives together.

Every single past life, while fictional and exceptionally creative, is rooted in some historical truth.

Barker’s style is unapologetically brutal, but she is a master at dark comedic timing as well. There are so many examples of that throughout the book, braided within the brutal and bleak lives of our “soul mates.”

Subtext(s)

I have no idea if this is what Barker meant to do, but the entire subtext of The Incarnations seems to be a great argument that there is no true “hell”, there is no “other dimension” of barbarity where “sinful” souls go for torment. No, “hell” is here on earth, and there are many examples of torment throughout history and in modern times.

Also, the idea of soul mates might be romantic, sure, but really, two souls being forever entwined and ripped apart brings with it a natural torment in itself. And this second subtext is driven home with such clarity, I leave each reading fully convinced.

Lessons Learned

When I read, I read for entertainment but also for education and to improve my own writing. So, when I really love a book, like I love, love, love this book, I ask myself what I love about it. Not in terms of plot, but in terms of writing style and aesthetic.

What I love about Barker’s style here and value most are the following:

- The vividness of the scenes; the attention to sensory details, even the most minor.

- The unapologetic brutality—it’s truthful to me, raw—how the real world truly is.

- The genius demonstrated in the braiding and the timing of dark comedy.

- The limited dialogue, limited to only that which is necessary.

- The infusing of poetic lines (even if Barker didn’t intend this, her writing led me to seeing poetry).

- The unabashed creativity, like off-the-charts, wild explosions of creativity.

- The transportation to modern Beijing and historical Beijing (I felt I was there).

- The infusing of historical facts into a fictional narrative (it was educational—I Googled several items to learn even more).

- Most of all, the blending of genres. Here, historical fiction, speculative fiction, magical realism, mystery, and dark comedy, all combine into the apex-pinnacle-best-concoction, the most treasured witch’s brew, the exact blend I seek constantly. It is exceedingly rare to find.

A side rant here: While they are there to be found, and I can come up with a few good examples, I believe it is exceedingly rare to find these amalgams of genre, especially in the US market, given the constant push to place authors and books in single categories—easier to market, we’re told. I reject that notion. And please do come to me with your examples to prove me wrong: I want all the titles, I will likely want to read them.

DAVID: As the excerpts I selected probably indicate, I also found the book’s style mesmerizing, and the general story world and its logic fascinating.

The book in many ways reminded me of two Chinese classics, which the author mentions in the text and which I studied in college, Journey to the West and The Dream of the Red Chamber. Both have that combination of humor, myth, magic, and an unapologetic earthiness.

I have to admit that one of the risks Susan Barker took with The Incarnations—contrasting fascinating past lives with the dreary, intractably gray life of Wang in present-day Peking—didn’t always work for me.

I also found Wang a bit too clueless, and his present-day life and his family conflicts seemed comparatively banal when contrasted with what he experienced in previous lives.

One section where Barker made contemporary Peking compellingly vivid was when she had Wang visit the vast open-air market and the shady enterprises operating on its fringes:

Vegetable stalls of pesticide-sprayed spinach and earth-clodden turnips. Racks of carcasses hanging from hooks, ribs and spinal cords exposed. A butcher in a bloodstained apron slams his cleaver, seasoning a joint of pork with ash spilling from his cigarette. Wang roams from stall to stall, gradually filling his bag with items on Yida’s list. Bean curd. Spring onions. Vinegar. The ground is slippery with plums fallen from a fruit stall and trampled to pulp. The children of the migrant vendors chase about, skidding through the mess as they play tag. Wang buys two jin of rice. The rice seller hands Wang his change without looking away from the old Bruce Lee movie on his laptop, perched above the till. The dusk is balmy and suffused with spring.

Wang detours down an alley behind the Golden Elephant pharmacy, passing a Uighur selling fake Rolexes and a shifty-looking man lurking by the tobacco and liquor store, on the lookout for police. Wang has seen him before and knows he is a seller of identities: student IDs, graduate diplomas and other papers. Documents, both stolen and forged, used by migrants to gain employment in the capital. Another man nearby is peddling blank receipt booklets from hotels and restaurants for officials to claim fraudulent expenses. He rustles a wad of banknotes, hinting at a profitable day’s trade.

At another point, Wang remarks on the contrast between the world he sees and the propaganda the government issues to justify it:

There is no harmonious society, he thinks, only the chaos of people with crooked teeth and no manners, trampling on each other.

That’s all great, but they were a bit too few and far between for me. Meanwhile, compare those sections with this from one of his past lives (which is but one of several fascinating examples):

Flames leap in the hearth, and the sorceress chants in an ancient tongue and tosses into the fire a mysterious dust that flashes sulphurous and bright. She decants into vials potions to cure heart-sickness, abort a foetus or punish a husband who rapes the twelve-year-old servant girl. She sells bottles of deadly nightshade, and hallucinogenic venom extracted from the heavy-lidded toad she keeps in a bamboo cage. She sells amulets and anti-lust charms. She sells a poultice to the cabbage-seller to grow back his amputated foot.

I was particularly intrigued by the idea that fate, which clearly has no affinity for the human lives it controls, has thrown these individuals together so they can torment each other across the millennia. But there may be a way to rebel against that fate, and that is what the narrator/letter-writer seeks to do by reaching out to the otherwise oblivious Driver Wang.

That said, it wasn’t until going back and re-reading my notes that I focused on that more redemptive interpretation. That may be more my fault than Barker’s, but I wonder if you came away with the same impression—that reincarnation has no enlightening purpose as in Hinduism, where we progressively atone for our past sins and limitations. Here it just seemed to be one hellish torment after another with no hope of escape or even understanding, despite the existence of genuine love—and horrific betrayal—in each lifetime. (You suggest a similar takeaway in your discussion of subtext above.)

And yet, this begged the question—why does the narrator/letter-writer/soulmate have insight into her and Wang’s past lives, but Wang does not? That was never satisfactorily explained to me. Now that I see that the narrator has a plan, to rebel against fate and thus save her and Wang from this endless cycle of misery, I can see where this is crucial, but I’m still in the dark as to why or how she comes by this awareness.

SHANNON: David, I really love all the excerpts you quote above. I agree that they demonstrate how vivid and consuming many of the scenes are. And I agree, the chapters in present-day Beijing are bleak in comparison.

But for me, that’s part of the allure of the book. In other words, I couldn’t have the spikes of excitement when I reached a “historical” soul mate chapter without living the choking greyness of Wang’s present life.

Isn’t this the entire manipulation of the soul mate who is writing the letters? The “come hither” finger-draw he or she is tempting Wang with? Come, Dear Wang, come with me, your soul mate. Your life if awful. Your wife, Yida, is awful. I will show you a larger life. A colorful life. And we will fix all this.

Indeed, for me, one of the best dark comic chapters is a very short one. It’s the soul mate’s Fifth Letter, Chapter 17, and she says almost exactly this:

Yida is a parasite. She saps your energy as you sleep, Driver Wang, so you wake exhausted, feeling as though another decade has been dumped on you in the night. She weakens your immune system, which is why your lungs are losing the battle against the carcinogenic air.

So when you’re reading the present-day Beijing chapters, I think Barker wants the reader to feel this parasitic leaching, this greyness, this lethargy, this smog. Because that is how the soul mate wants Wang to view his life. Although the present-day chapters are supposed to be from Wang’s POV, are they really? Is not everything colored by the soul mate?

You asked about the redemption possibilities of reincarnation and whether I saw any in this book. I agree, it does seem as if each life is one hellish nightmare to the next. I’ve thought a lot about your question. I’ve read the book twice and then went back through just the different reincarnation chapters to chart out what I think might be the character arc here. It is subtle.

First though, I continue to believe, and feel even more strongly after the second and third reads, that the entire subtext of this book is that life is hell. So many examples in history and in our daily lives prove this out. Life is not rosy and neat as the network sitcoms map out in formulaic, feel-good scripts. Here’s a laugh-track pill, go to bed, sleep. Repeat tomorrow.

And I need not remind our readers what original fairy tales really are, unedited, unaltered for modern consumption—the violence, the utter dark grimness.

Life is raw and violent and a hellscape for many. And there is no other separate “hell.” Again, this is my main takeaway from the book. Not sure if I’m right about that, but this interpretation colors my answer to your question about redemption.

Given that we are in “hell,” and there is no other hell, what is there to be redeemed to? Where else would you go?

Perhaps part of the point here is, this whole rosy notion of “do good and you will be rewarded and live eternally with a loving soul mate” is bogus? Perhaps the frustrating struggle for many against the powerful, the patriarchy, the warlords of life is to see only the meaninglessness and impossibility of improvement to some better existence. Perhaps that feels true. Still, I do see improvements with these characters as you progress through their different lives, and those improvements, charted over the long arc of eternity, might indeed lead to a more peaceful existence for them.

[WARNING: SPOILERS AHEAD: END OF SPOILERS IS MARKED]

Here’s one way to view Wang’s and his soul mate’s character improvements, or at least, evolution:

First up, Night Coming (letter-writer/soulmate) is the incest daughter of BitterRoot (Wang), who raped his sister. BitterRoot (Wang) abandons his daughter (soulmate). This is pretty much the most awful “character” of Wang’s incarnations. He is a rapist and a deadbeat. In contrast, Night Coming is a pretty solid, stoic, and fairly hilarious character.

Second up, the two soulmates are captive slave boys in Genghis Khan’s army. The soulmate is obsessed with this incarnation of Wang, living for the touch of his body and his attention. The Wang incarnation is a provider and warrior and seemingly fearless. When the soulmate kills off Wang’s would-be attackers as they sleep, Wang leaves the soulmate, disgusted by the dishonorable and cowardly nature of the murders. In a stark turnabout, Wang refuses to view what the soulmate did as protecting him. He walks off, and the soulmate murders him. In this chapter, it seemed to me almost as if the Wang character was over-correcting for the dishonorable and cowardly way he lived in his last life. As if any amount of cowardice or dishonor repelled his very soul.

Third up, both the soulmate and Wang are among sixteen concubines to a ruthless emperor, with the soulmate serving as a kind of older sister-figure to a fourteen-year-old Wang. The soulmate offers protection of Wang by, in my view, forcing sexual favors from her. So while Wang ultimately betrays the soulmate in spectacular fashion, and perhaps the reader is to interpret this as a serious betrayal by Wang alone, given the leaching of sexual favors from a fourteen-year-old and the circumstances, I felt the betrayals were almost equal. As if their power dynamic was equal for the first time in their lives together.

Also, this is the first chapter in which there seems to be an inkling that the soulmates sense a connection beyond the worldly life they’re actually living. It comes at the end, when the soulmate is dead and looking at Wang in the mirror. Words are said.

Fourth up, a boy (the soulmate) lives in a village built on the sea, and one day, as he is about to be killed by ruffians on the docks, an Englishman (Wang) steps in and saves him. An opportunistic save, as he was down at the docks at the right time to intervene. He takes the opportunity to prime stories from the soulmate boy on what it’s like to live in the sea village. The Englishman is writing a book about it all.

This chapter is the first demonstrable improvement of character in that the boy and Englishman seem to actually care for each other’s well-being, beyond the need to rely on each other for mere survival, as in the past chapters. Through a series of truly brutal mishaps, however, the Englishman (Wang) kills the soulmate boy, but not out of any marked betrayal. Only out of fear and justified (if confused) rage.

Fifth, a school for girls during the Cultural Revolution. This chapter is truly brutal. And yet, the Wang character, who has considerably more power than the soulmate character, proactively steps in to help her, saying, “How could I not want to be your friend, Moon?…When I am with you, I’m so at ease. It’s as though I have known you all my life…”

This fifth chapter is like a spike in the ground. This is the evolution of their relationship, to now outwardly take action for the other because of a sense of knowing each other “all my life.” And it is in the the next life, the modern Beijing times, when that “knowing” is “all my lives.”

I guess, David, this is how I’m viewing the progressions, this measured cranking of the wheel, this subtle evolution of knowing connection—a sense that unfurls in minor chords, an inch in this life, an inch in that, to the point where the sense cannot be denied and action is taken because of it and not merely for the needs of the flesh.

If those minor chords were more dramatic in each life, then soulmates wouldn’t need “eternity” to perfect their combination, their “sense” of being one in a peaceful harmony. That plateau of existence must come one brick at a time, amongst a billion bricks. This is why it means so much to say you’ve found your soul mate, eh?

As for your question, why then isn’t Wang aware of these past lives? Why doesn’t he have this sense as the soulmate does? It’s a good question. It could be that Wang does, underneath, but refuses to acknowledge it, as he is too afraid of having the same debilitating mental illness as his mother. So he’s buried his true self.

Or, the interpretation I refuse to take, but one could take, is that the “soulmate” is actually just making all of this up, in acting out her own delusions. But I really don’t like that stale interpretation, as it takes away the beauty and magic of this book. I choose to believe these are, indeed, the letters from a soulmate.

[END OF SPOILERS]

DAVID: That is an utterly fascinating look at the progression of their incarnations. I hadn’t seen that, and I think you’re onto something.

I also agree that having the soulmate simply be delusional is cheap, wrong-headed, and impossible to reconcile with the clarity and intensity of what she describes. For whatever reason, the soulmate has acquired in this incarnation an awareness of all the lives that came before. As much as I think some explanation of how she came by that awareness—and why Wang hasn’t—might have been instructive, I don’t think it’s a fatal flaw.

SHANNON: I have to add that on my second reading, and then my third of the different incarnation chapters, I fell even more in-love with this book. So much so, I bought three more copies of the UK paperback edition, because that is the best cover (it’s blue and mystical and beautiful). I bought three because I live in fear someone will visit my library, and I’ll suggest they read The Incarnations, as I inevitably do, and they’ll forget to return it. So now I’m insured.

I am one of those barbarians who mark up books, fold pages, and underline lines that stop me cold. My “study” copy of The Incarnations looks like a college library copy of Anna Karenina. Full of student notes and highlighting. A veritable mess. So this copy of mine is treasured, and perhaps I’ll be buried with it. Kidding. Maybe. Wink

I think what I’ve set out above shows my personal, and very subjective, admiration of tales with characters who are jagged and raw and don’t necessarily follow a clear, refined arc. I don’t know if that means I like unreliable narrators (sometimes I do, sometimes I don’t). I don’t know if I’m more comfortable in books that depict the messiness, the rawness of real life. I don’t know. But, to me, this somewhat unsteady balancing of soulmates over a very long history seemed both fantastical and true. I like that mode of storytelling, it provides a methodology that keeps the reader unable to predict the outcome.

I saw something somewhat similar, although in a wholly different kind of book, by Denise Mina, in Conviction. Although Conviction is not nearly as brutal at The Incarnations (yet, there is brutality, for sure), I loved how that entire plot was a bit topsy-turvy (in a good way, in a way that allowed me to feel the plot points were not predictable).

There’s a great paragraph in which the main character talks about people having boring lives and thus boring stories to tell, stories that don’t reveal the rawness and messiness of life. And that caught my eye, as it was what I was trying to say here, about The Incarnations. From Mina’s Conviction:

I’ve met people that nothing much ever happened to. They live in the same place, they go on holiday, come back, eat food, day after day. No ups, no downs. I used to wonder if they were lying or unobservant or had somehow arranged their fate that way. But it’s just random dumb luck. Too much has happened to me. Too many lives. Too many events.

DAVID: I can’t imagine a better way to end. (BTW: I’m a big fan of Denise, both her work and her, personally).

In accordance with Shannon’s request, can you name similar genre-bending or genre-meshing novels that simply dare the marketing wonks to label them?

Are there any works you can name that somehow enhance their sense of realism by being seemingly “fantastical”?

Do you agree with Shannon that it’s actually characters who do not experience a conventional arc—weakness to strength, sin to redemption, power to destruction—who actually feel more engaging and real?

David and Shannon, I really enjoyed this conversation about the Incarnations. I’m not sure I can be tempted to read this though–I grew up on the very Hindu idea of reincarnation, which has a purpose, not so capricious as depicted in this book. But I am definitely intrigued and will look it up. I like that the soul mate is trying to defy fate.

Reincarnation taps into is the concept of eternity; it is something people of all different cultures ponder. Memento mori, no? This is why I also believe in a heaven and a hell, but I also see it as something one chooses. Let’s put it this way, if a person doesn’t love God, why would he or she want to be in heaven? When I was in my 20s, living a life of indulgence, not sparing a thought for God, I would’ve chosen hell. I was in hell, only I didn’t know it because I wasn’t suffering. Yet man can create hell–the Jewish Holocaust, Stalin’s gulags, Mao’s China, Khmer Rouge in Cambodia, and we can continue to add to this list. I’m reading Man’s Search for Meaning by Viktor Frankl at the moment and I’m very conscious that man has the capacity to do great evil but it is our response that matters. We can lift our hearts and minds to heavenly things even in our darkest hour. Interestingly, he mentions Death in Tehran and it makes me wonder, can you trick Fate? I don’t think so. Thank you for this interesting book and discussion.

One of my favorite books that’s beautifully written and explores the idea of soul mates/reincarnation is The Gargoyle by Andrew Davidson. I think you both will enjoy it tremendously.

Thanks for chiming in, Vijaya. Somewhere in my reading past I’m sure Frankl has crossed my desk. I’ll check out the Davidson book.

Hey David and Shannon – I mainly want to say how delightful and refreshing reading today’s post is for me. I have so few opportunities for deep-dive discussions about books I love with someone else who loves them as much as I do (or somewhere near). And I am so intrigued by The Incarnations. Even after reading the spoiler section (me resist? Yeah, right).

As for genre-bundling, I’m going to say it, fully understanding that I’m talking about a genre category: Have you read any adult epic fantasy lately? (Please resist the temptation to roll your eyes.) Of course the label is used to market the books (where to put them in the store, etc.). But that and the scale seem to be the last few things holding the genre together these days. Genre-bundling seems to be the order of the day. I’m thinking of authors like N.K. Jeminsin, R.F. Kuang, Nnedi Okorafor, Neil Gaimen, and so many others.

Just a thought from WU’s friendly neighborhood epic fantasy geek. Again, thanks a lot for pulling us in to your epic and analytical conversation. Stay healthy! Enjoy reading as you practice your social distancing with your dry-scaly but oh-so-clean hands.

I was so hoping you’d chime in, Vaughn. I think the very conjunction of “adult” and “fantasy” naturally suggests a certain tendency toward genre-bending.

And great list of authors. Since we’re all likely going to be spending more time at home for a while, it couldn’t be more timely.

Vaughn, to the adult fantasy works you mention, let me add the Chronicles of Thomas Covenant, by Stephen Donaldson, which began coming out in the early/mid 1980s. The first six books in that series got me through an extended rough time when I needed good escape reading. That saga delivered. If you aren’t familiar with those books, you might give them a try.

Vaughn, as for adult epic fantasy, do you know the Chronicles of Thomas Covenant by Stephen Donaldson? The series began coming out in the early/mid 1980s. I read the first six books and loved them (so much so that I wrote a few fanfic scenes—never to come to light, of course).

Someone once recommended this series to me, but I never got to it, and then forgot about it.

Thanks, Anna! Happy Friday!

Computer glitch: sorry for (almost) duplicate post!

David:

Your close reading with a fellow writer was insightful and fascinating (more so than some novels I’ve read). I hope other WU contributors will follow your lead.

Thanks, Christine. Shannon deserves the credit — she was the real impetus behind the discussion.

Fascinating discussion, David, though I am not sure if I will read the book – it sounds too bleak for my current mood.

Reading suggestions:

Cloud Atlas by David Mitchell – a literary novel composed of nested stories, definitely genre-bending and genre-blending with great skill. Quote from Wikipedia (it’s OK, I have actually read the book):

“The author has said that the book is about reincarnation and the universality of human nature, and the title references a changing landscape (‘cloud’) over manifestations of fixed human nature (the ‘atlas’).”

The Years of Rice and Salt by Kim Stanley Robinson – classified as science fiction; an alternative history that includes reincarnation of the central characters. A striking, thought-provoking read. It’s based on how history and culture might have changed if almost all of Europe’s population had been wiped out by the Black Death (bubonic plague.)