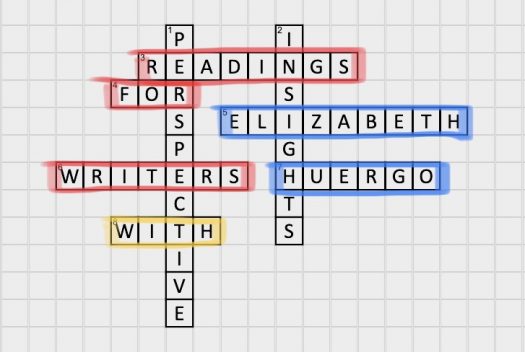

Readings for Writers: Writing in Hope–and History

By Elizabeth Huergo | January 28, 2020 |

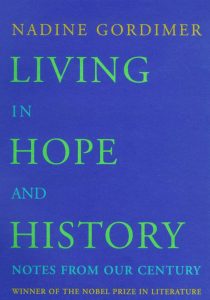

In her essay “Three in a Bed: Fiction, Morals, and Politics,” Nadine Gordimer reflects on the role of the writer, a relevant reflection for us, especially now, at the beginning of a new year. Who hasn’t asked what is the purpose of my story? Why write?

In her essay “Three in a Bed: Fiction, Morals, and Politics,” Nadine Gordimer reflects on the role of the writer, a relevant reflection for us, especially now, at the beginning of a new year. Who hasn’t asked what is the purpose of my story? Why write?

If you’ve never read Gordimer, you should know she took on a fight that wasn’t hers. She was white, Jewish, and South-African. She could have chosen a subject that circumvented controversy. Instead she wrote about apartheid without standing on a soapbox wagging her finger at racists and without reducing the brutality of white supremacy to a factoid, a matter of background or setting.

Gordimer did what was difficult, focusing on the distinction between what a writer sees and what she is told she sees; between “the real meaning of words” and “ready-made concepts.” As she explains in “Three in a Bed,” the first essay in Writing in Hope and History: Notes from Our Century, “[a]n accurate and vital correspondence between what is and the perception of the writer is what the fiction writer has to seek, finding the real meaning of words …, shedding the ready-made concepts smuggled into language by politics.”

Gordimer did what was difficult, focusing on the distinction between what a writer sees and what she is told she sees; between “the real meaning of words” and “ready-made concepts.” As she explains in “Three in a Bed,” the first essay in Writing in Hope and History: Notes from Our Century, “[a]n accurate and vital correspondence between what is and the perception of the writer is what the fiction writer has to seek, finding the real meaning of words …, shedding the ready-made concepts smuggled into language by politics.”

She reminds us that journalists report facts. And fiction writers? Fiction writers “expose” and “discard” the language, the packaging of those facts. Then she presents an example as real and provocative as any cited by Orwell in “Politics and the English Language.” She asks how, in practice, a fiction writer would address the similarity among the terms “final solution,” “Bantustans,” and “constructive engagement”:

…[H]ow would you refer, in a novel, to the term ‘final solution,’ coined by the Nazis; the term ‘Bantustans,’ coined by the South African government in the sixties to disguise the dispossession of blacks of their citizenship rights and land; the term ‘constructive engagement’ coined by the government of the U.S.A. in the seventies in its foreign policy that evaded outright rejection of apartheid–how would you do this without paragraphs of explanation (which have no place in a novel) of what their counterfeits of reality actually were?

Answer? Fiction writers, while neither polemical nor didactic, tell the schism between what is happening around us and the language used to describe it. We do so because we are living cramped “three in a bed”; because we are “living in hope and history.”

In one of the essays near the end of the collection, “The Writer’s Imagination and the Imagination of the State,” Gordimer returns to the choice fiction writers have of challenging how facts are packaged. As she puts it, “[t]he State wants from the Writer reinforcement of the type of consciousness it imposes on its citizens, not the discovery of the actual conditions of life beneath it, which may give the lie to it” (italics original).

It’s the first month of the New Year, and I want to be hopeful–not by devising a list of impossible resolutions, but by centering down on my own sense of purpose and craft. As a Latina and a writer, I begin to wonder: who challenges the way the story of Óscar Alberto Martínez Ramírez was packaged for our consumption?

In June of 2019, Martínez Ramírez was found lying face-down in a riverbank, his 23-month old daughter Valeria dead, still tucked under his tee-shirt. He was 25. According to the headlines, the image of their bodies is memorable, disturbing, and horrific. According to the headlines, more than 500 people died trying to cross into the US last year, so it turns out father and daughter were two out of many, many people who died on that border, many children who have been detained, separated from their parents, traumatized.

Journalists inform us of these facts. The language they use reinforces our own way of seeing. It does not help us remember Martínez Ramírez and his family, and the families of every soul who dies crossing the border. It packages Latin-American migration northward as something without history, economic or military.

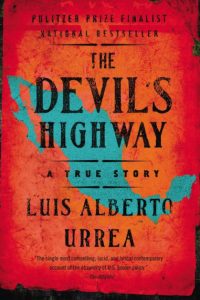

The situation demands the presence of a fiction writer willing to point to the terms “final solution,” “Bantustans,” and “constructive engagement” and tell the story of their equivalence. Luis Alberto Urrea takes on the task in The Devil’s Highway, the factual story of the Yuma 14–the men who died crossing the border in May 2001

The situation demands the presence of a fiction writer willing to point to the terms “final solution,” “Bantustans,” and “constructive engagement” and tell the story of their equivalence. Luis Alberto Urrea takes on the task in The Devil’s Highway, the factual story of the Yuma 14–the men who died crossing the border in May 2001

To repeat, the narrative is both fact and story. Urrea offers us the map of the terrain those men crossed. He also explains how even maps lie. On the border, a “sign” is evidence that someone or something has disturbed the terrain. And “sign cutting” is the act of detecting these signs. In the desert, Urrea tells us, “[t]here is room . . . for scholarship as well as sport”:

“Cutters read the land like a text. They search the manuscript of the ground for irregularities in its narration. They know the plots and the images by heart. They can see where the punctuation goes. They are landscape grammarians, got the Ph.D. in reading dirt.”

Urrea tells us the facts. He also points out that facts are based on interpretation. The imagination can help us close the open loops of what we think we know.

Here, for example, is Urrea describing the bodies of the 14 men, “dense and dark,” inside zippered bags, waiting to be transported to a lab in Tucson before returning home:

“The cost of using the vehicles, the drivers, the crews, the gas, was more than they could have earned in a month. But there was no worry now, no thought. Just rest. … Sewage treatment ponds cast up brown shit-fountains as if they were saluting them.”

The State of Arizona spent more in the transportation and analysis of the men’s bodies than the dead men would have ever considered possible. Urrea dwells on the irony of those numbers. He places those numbers in proximity to a fountain of sewage.

He also reanimates their bodies, giving them in death their humanity, projecting through them the wishes and preferences that made these men human beings and not numbers or destitute brown bodies. Reymundo Sr. loved his son, Urrea insists:

“Reymundo Sr. would likely have preferred to have been in the same bag as his boy, but they were kept apart. Reymundo Jr. was alone, lost and small inside the bag, almost swimming in all that black rubber space, sliding around as they drove, and now on the icy metal table. They could have torn the rubber and held hands, but they were resigned to their fates.”

What Urrea accomplishes in The Devil’s Highway is neither polemical nor didactic. He is as respectful of the members of the Border Patrol as he is of the 14 men who died. He is factual. He uses his imagination. And he drives a wedge between what is happening on the border and the language used to describe it. He gives me hope.

How do you see your role as a writer? Why do you write?

That was an inspiring post Elizabeth, so thank you for it.

My role as a writer? I hope it is to expose the complete truths that are a result of society’s tendency to make hasty and hateful decisions.

Thank you for taking the time to post a comment, James. I share with you that sense of writing as truth-telling. My very best, Liz

Fantastic article. Thank you for this.

Thank you, Susan, for taking the time to comment. Liz

Thanks for this, Elizabeth.

Seeing Urrea’s name and cover in your post, I expected you to be entering the swirling opinion around the January 21st release, promotion, and criticism (and huge advance) associated with Jeanine Cummins’s AMERICAN DIRT.

I have been consumed by it because 1) I read an ARC and know the publisher and 2) my own WIP deals with social issues (that could easily veer into polemics) and, like Cummins, explores experience of races and cultures into which I am not born. This could make me a similar target of critics.

I have not read read Urrea’s work yet, but you label it fiction here while many others identify him as non-fiction. The sections you quote and your description make me think it is narrative non-fiction. How does Urrea handle POV here to make it story when he seems to be adhering to the facts and interpreting them, enriching them with cultural and even spiritual views, territory that journalists cannot travel. It sounds more like elegant commentary. For instance, are there character arcs?

I will read Urrea next, but I’m sure you have views on this subject and I hope you address them in a post very soon. Particularly, the ‘who has the right to write what?’ question, which really pertains to fiction.

Tom, you are well ahead of me on Cummin’s recent work and the controversy around it. I haven’t read AMERICAN DIRT, so I can offer neither opinion nor argument. I do believe, however, she identifies as Latina and that she is from Puerto Rico.

Personally, I think it is an error to assume an absolute equivalence between race/ethnicity and the stories we may or may not tell; the things we may or may not do in this life.

I’m Latina (Cuban). When I was in graduate school, I would apply for teaching positions in my field (British Romanticism). I can’t tell you how often a panel of white interviewers opened with a request that I speak to them about Sandra Cisneros. I was there to discuss Mary Shelley, Wordsworth, Byron. The dissonance for my audience between who I was/am and my chosen academic field was palpable.

On the matter of genre (form) in Urrea’s THE DEVIL’S HIGHWAY, I can offer a few points.

We are living in a particular historical moment that is obsessed with classification of fact from fiction. It’s an economic obsession at heart: we value business, science, things that can be quantified, things that make money. (We fund the Sciences more readily than the Arts.)

Joseph Campbell wrote/talked about how, as a culture, our cathedrals are sky-scrapers. We measure our well-being by what the Dow is doing; we consider the quality of a new movie according to its box-office draw.

Other cultures (today) do not consider the world in the same way. Other eras have not considered the distinction between fact and fiction in the same manner.

For example, Defoe’s A JOURNAL OF THE PLAGUE YEAR and MOLL FLANDERS blur the line between memoir and fiction without qualm. Woolf blurs the lines between poetry and prose (any of her novels), as well as the line between essay and short-story (“A Room of One’s Own”) to brilliant effect.

The book of Urrea’s that I discussed is classified as “Current Events/Non-fiction” for purposes of marketing, and that’s okay. The book includes maps (geography), history, archaeology, biology (what happens to the human body in desert heat).

And then there is Urrea, the poet and the novelist. Read it and see what you think.

And please know how grateful I am to you for your thoughtful response.

Cheers, Liz

And Liz, I am truly grateful for your thoughtful response.

Thanks, Elizabeth. I read Gordimer’s fiction, followed her life story, and mourned her death in 2014. She saw the things many did not see. That is true of us now, of hiding behind our privilege. And the question is becoming so present–how can we communicate that anguish through our writing? Because I cannot go to the border and help. I did send children’s toys to the Florence Project–that reaches out to the separated and frightened. How can my fiction help them? Does Cummins new book help them? I also have a bio of my sister-in-law’s husband who escaped apartheid when he was in his teens, came to the U.S. and became a successful neurosurgeon. But so far, no one wants to read that story. Thank you for awareness. We all need more of it.

It sounds as if you do an enormous amount already, Beth. You are conscious and conscientious.

Tell what you see.

It’s much harder than it sounds, of course. Luckily we are in the same creative struggle together.

Please know how much I appreciate your comment. Thank you always, Liz

Thank you for this thought-provoking post. It’s been a while since I’ve read Gordimer, and this is a timely reminder to look back at the subjects she chose and how she presented them. And I’ll add Urrea to my TBR shelf.

You’ve also touched on the question that’s been vexing me for a while: Why do I write?

The answer I’ve most often used is: Because I enjoy it.

But that answer doesn’t feel sufficient anymore.

Most recently, I realized that I write to figure out what I think, but that’s also not enough.

I’d like to say I write to speak truth to power, but none of the things I’ve written to date have been weighty enough to earn that designation.

You’ve asked lots of good questions, and I clearly need to spend some time figuring out what my answers are.

Ruth, I share with you those same reasons, as well as the sense that those very reasons are not enough.

I think of P.B. Shelley’s “poet legislator” as well as the early Romantic poets’ moral sense, Wordsworth especially.

The word “moral” sounds quaint–at best. But I think as human beings we tell stories to reveal something about the world, something we want to share in a helpful way. (Aristotle’s “catharsis of pity and fear,” the role of drama, had a collective moral purpose.)

For me the reason for writing boils down to a mantra: this is what I see.

Then I share what I see.

I’m afraid that’s as far as I’ve gotten. :)

I very much appreciate your comment; thank you! Liz

Elizabeth, thank you so much for this thoughtful post. I’m adding THE DEVIL’S HIGHWAY to my to-read list for sure. It sounds like it will be a tough and necessary read.

I’m an Urrea groupie, Heather. His novels and memoir are wonderful reads. In my estimation, his work is underappreciated. Thank you for taking the time to respond. It was very kind of you. Liz

Why do I write – what I write? and How do I see myself as a writer? are conflated because the story I write is about a disabled woman who has tidied herself away in the space allowed by society to the disabled, and discovers she is still vital and interested and just as likely to become obsessed as any other person – in the kind of juxtaposition she never expected to happen.

You have to understand the limitations of chronic illness as boundaries to the possible: everything in your life is affected by something you can push a bit, but can never turn off. Managing that can be a full time job.

But it also allows an exploration of the opposite side, the side that demands of its actors the very best humans can give – as the price for the adulation.

Heady stuff. Best written from within.

I am grateful for your thoughtful post, Alicia. I share your sense about the depth of the process and its origin. Thank you, Liz Huergo

Liz, you have highlighted the distinctions between fiction writers (of novels, I add poems, plays, music), and the “factoids” found in journalists’ articles and the reporting of news. One, the former, includes the humanitarian perspective — the latter gives us “just the facts, ma’am.”

So, let me think about your question: why do I write? In a word or phrase — to balance the historical record.

A couple of reflections: Hayden White argues, “[t]here has been a reluctance to consider historical narratives as what they most manifestly are: verbal fictions, the contents of which are as much invented as found and the forms of which have more in common with their counterparts in literature than they have with those in the sciences.” Hayden doesn’t claim any falsification of information. The “verbal fictions” he contends, area grounded in a set of historical dates, events, and personalities in which the historian (journalist) will fashion a story; the same creative design found in the novel or short story.

My second reflection harkens back to the ways in which lynching was depicted in both fictional and non-fictional accounts. For example, when The New York Times or Chicago Tribune’s headlines reported a lynching, it would read, “A Negro Desperado Lynched, ”Another Negro Burned.” The victims were nameless, ageless, friendless and without family, neighbor or profession. Of course the intent was to justify the murders as necessary to maintain social order. On the other hand, the fictional plays, songs, poems of fiction writers of the period, and journalistic writings of anti-lynching crusaders (i.e., Ida B. Wells, Billie Holiday) exposed the human facts behind the faceless victims of government-sanctioned, carnivalesque lynching and mob violence. The victims in these fiction and non-fiction accounts were human being and were described as fathers, mothers, sons, daughters, spouses, educated, Christian, law-abiding “men” and “women.” They had names and families, and were well-known members of society. Their stories were told with sensitivity and a more balanced record of the horrific, historical event.

So, why do I write? Liz, I write (when I have a moment) so my, humble perspective will be added to the telling of American history.

Tuere, I enjoyed reading your comment and appreciate the reference to Hayden White. Historians until very recently were part of the Humanities. Then they decided collectively to become “social scientists,” stepping a bit farther away from White’s “verbal fictions.”

All I can add is that I sincerely hope you are writing down your perspective on the world around us every single day. We all need you.

Elizabeth, thank you so much for sharing this engaging essay. Your selection of prose from Urrea perfectly illustrates how storytellers (of both fiction and fact) provide the empathy-evoking texture unavailable in more surface forms of communication.

I can’t say with certainty why I write. I think I want to reveal something that is difficult to see – because it is elusive and because it seems easier to ignore.

Thank you for your comment, Teresa. I think you’ve hit on something of central importance. If writing were easy, it wouldn’t be as compelling. Remember Rilke’s words to the young poet who asked his advice? It is because writing is difficult that you must keep to the task.

A late comment to add my voice in praise of Luis Alberto Urrea. He’s a brilliant writer (and should have gotten that flaunted seven-figure advance some time ago). I’ve read his linked historical novels The Hummingbird’s Daughter and The Queen of America. Besides his wonderful gift with words, what makes these books amazing is the insider’s lens he uses to portray his characters and world. Did he write only what he knew, as we’re so often admonished? Nope. He too researched, imagined, and worked hard to create authenticity.

From Urrea’s web site about Hummingbird’s Daughter: “I worked for twenty years, on and off, trying to create this epic novel. I had to learn a lot of things. I had to learn Mexican history, revolutionary history, Yaqui and Mayo cultural history, Jesuitical missionary syncretistic history, family history. I had to study with medicine people and shamans, midwives and curanderas. That’s a big load of study for someone who didn’t much like school. But fortunately for me, I had all this juicy mind-boggling story to play with.”