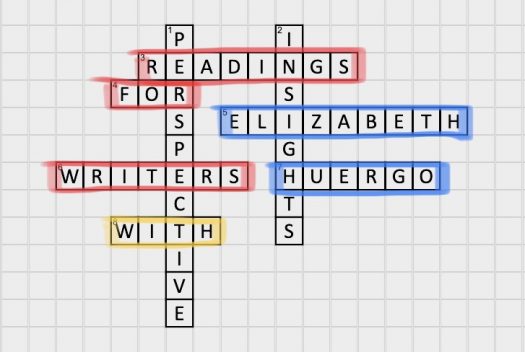

Readings for Writers: No Friend but the Pen

By Elizabeth Huergo | September 30, 2019 |

Writing is a solitary endeavor. When the solitude shifts and becomes self-doubt, I find solace in reading, especially stories that remind me of the hope that drives the will to tell a story and, through that telling, perhaps to make a difference. Writing is a gesture of hope based on the paradox that the unique story we tell is also the story we hold in common; that our solitude can become the basis of our shared humanity. Reading is as close as any of us will ever be to entering the consciousness of another person, to understanding the felt experience of another.

What happens when the material circumstances of a writer’s life are too remote to understand? I write from the perspective of a political refugee to an audience that, for the most part, has little to no direct memory of immigration, of having been set adrift from their ancestral homeland, unmoored from language and family by a force well outside any one individual’s control. When my solitude shifts, reading brings me back to myself. Reading helps me understand how other writers address problems of form, the shape of a story; and it reminds me no story occurs in a vacuum “outside” of history but rather in a material context driven by the decisions we make and the decisions to which we acquiesce, collectively and in silence.

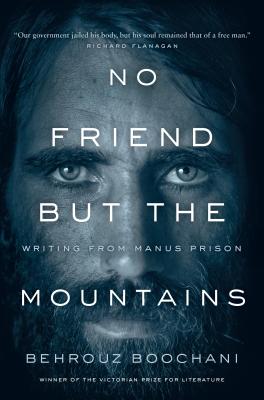

In frustration at my own limits, I turned recently to Behrouz Boochani’s No Friend but the Mountains: Writing from Manus Prison. Prison narratives demand a great deal from readers, and this one is no exception. Boochani, a Kurdish-Iranian writer and scholar, fled Iran in 2013 and lived for months as an undocumented refugee in Indonesia. On his first attempt to get from Indonesia to Australia, the vessel capsized. On his second attempt, he nearly drowned; the boat was intercepted by the Australian Navy; and he and his fellow asylum-seekers were taken to Christmas Island. Boochani spent one month on Christmas Island, then he was transferred by the Australian government to a detention center on nearby Manus. Like so many thousands of fellow refugees, he went in search of asylum and found instead a Kafkaesque place–an extra-judicial no-man’s land between hope and despair, neither salvation nor purgatory, where he has been since 2013.

As writers we might be tempted to classify No Friend but the Mountains as an interesting memoir. Look deeper, however, and discover in Boochani’s work a testament to the will to write, to represent his experience to an audience that probably cannot understand, however empathetic and broad-minded. Indefinite detention is a legal abstraction for most people living today in the wealthiest nations of the world, where the life or death search for political asylum is generally perceived as a personal choice and not the foreseeable outcome of a long history of neocolonial military and trade policies. Will we understand or won’t we? Regardless, Boochani tells his own story; he tells the story of political refugees, of asylum seekers, and our shared humanity.

Writing from the squalor and violence of a detention camp, Boochani composes No Friend but the Mountains in fragments–text messages sent out surreptitiously from prison and later translated into English by Omid Tofighian. The narrative is shattered, its form reflective of a shattering experience. At points the author’s observations, distilled, become allegory. There are scenes that evoke Brecht and Beckett and aphoristic reflections reminiscent of Adorno. There are poems so starkly literal that, as John Felstiner observes of the Holocaust poet Paul Celan’s work, “reality overtakes the surreal” (Paul Celan: Poet, Survivor, Jew).

Writing from the squalor and violence of a detention camp, Boochani composes No Friend but the Mountains in fragments–text messages sent out surreptitiously from prison and later translated into English by Omid Tofighian. The narrative is shattered, its form reflective of a shattering experience. At points the author’s observations, distilled, become allegory. There are scenes that evoke Brecht and Beckett and aphoristic reflections reminiscent of Adorno. There are poems so starkly literal that, as John Felstiner observes of the Holocaust poet Paul Celan’s work, “reality overtakes the surreal” (Paul Celan: Poet, Survivor, Jew).

Here, for example, is Boochani’s description of the journalists designated by the Australian government to record for posterity the transfer of undocumented refugees:

The journalists are staking out the situation like vultures: waiting until the wretched and miserable exit the vehicle; eager for us to come out as quickly as possible, to catch sight of the poor and helpless and launch on us–

Click, click /

Waiting to take their photos /

Click, click.

–and dispatch the images to the whole world. They are completely mesmerized by the government’s dirty politics and just follow along. The deal is that we have to be a warning, a lesson for people who want to seek protection in Australia.

Boochani’s language refuses metaphor, refuses poeticizing of any sort. The world he describes is a place without sanctuary, where we revel in the “collapse of others.” “The weak,” as he observes, “always consider themselves powerful when they see others suffering. But the collapse of others appeals to the oppressor in all of us. The collapse of others becomes a cause to celebrate our own state.”

Despite being held in indefinite detention, Boochani turns inward in search of a story about himself, reaching back into his past to consider the choices he faced. “When I was younger,” he reflects, “I had wanted to join the Peshmerga. I wanted to live my life away from cities. I wanted to live my life in the grip of apprehension, out there in the mountains, and participate in the ongoing war.” He wanted to join the Kurdish fighters in northern Iraq and become one of the peshmerga–literally, one of “those who face death.” Each time he felt tempted to join, however, “[he] was impeded by some kind of fear masked by theories of non-violence and peace.”

The choice was stark, the gun or the pen. In another sense, though, the choice was devoid of difference. Both were choices of “language”–the language of the mountains, of “armed resistance,” or the language of the cities, of writing. “For years and years,” he explains,

I contemplated finding protection within the mountains, a region where I would have to take up the gun, a region where I would be among those who couldn’t comprehend the value of the pen, a region where I would be obliged to speak their language, the language of armed resistance. But every time I pondered the power and glory of the pen, I would go weak at the knees.

This “child or war” who grew up in Ilam, the Kurdish region of western Iran, knew too well what it meant to live between Iraq and Iran, between secularists and theocrats, between competing responses to Western imperialism. Whatever he chose, gun or pen, would turn him into one of “those who face death.”

He became a teacher and a journalist, promoted Kurdish culture and identity, and worked to found the magazine Werya, using “the power and the glory of the pen” to tell the story of Kurdish culture. He wielded his pen from a political margin, from material circumstances that had already exiled him, writing to an audience of Kurds that still retained a sense of place, language, family. He was so effective the Iranian government sought to detain him, just as it had detained his friends and colleagues. Facing death, Boochani fled and ended up in Indonesia, where he lived starving and unable to return to Iran, for “having to return to the point from which [he] started would be a death sentence.” His only recourse was asylum.

Reality has overtaken the surreal. The bodies of refugees are washing up dead on ocean shores and riverbanks everywhere because those of us who have so much bounty are behaving as if we don’t have enough soap and toothpaste and stoop labor to spare. The recurring images of children lying dead at water’s edge shock us momentarily. But the images don’t seem to galvanize actual change. They certainly don’t return us to the (Latin) root of “sanctuary,” which is sanctus or holy, a sanctuary being a place consecrated and inviolable, a refuge against distress or harm, a place of retreat and shelter, a temple, a church. Nor do the images help us recall the ancient concept of asylum as a form of mercy that exceeds the limits of human law, a concept that was secularized and enshrined in successive documents after the Second World War, the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948) just one example.

As writers, we have an obligation to read the stories of refugees and to understand what propels people in Syria, Iran, and Iraq; Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador to cross borders. We have an obligation, as fiction writers especially, to write the greater truth about the history that drives the felt experience of another, to metamorphose the tragic into the hopeful by taking up the pen. Boochani warns us how hopelessness radicalizes people, catalyzing the belief in violence as the only path to political expression, to self-determination:

This I know: courage has an even more profound connection with hopelessness /

The more hopeless a human being, the more zealous the human is to pursue increasingly dangerous exploits.

The story of our time is exile–the life and death search for political asylum, refuge, sanctuary. It’s an ancient story about how chickens come home to roost. It’s also an opportunity to be hopeful, to find healing and reconciliation through the pen.

Do you believe in the value of writing as a source of healing and reconciliation? Do you struggle with telling a story that is difficult for your audience to understand? Does reading inform your writing practice?

Learn more about No Friend But the Mountains: Writing from Manus Prison at IndieBound.

Thank you, Elizabeth. Your post comes right on the heels of a book I finished just last night, The Cartel, by Don Winslow, an overwhelming fictionalized account based on real events from Mexico’s drug wars.

Boochani’s nonfiction account sounds doubly deep and hard, a further reminder that the displacement of human lives knows no bounds, moral or geographical. Winslow’s fiction shows how fear and terror drive the empowered to desperate measures. These masters of terror live in a hell of their own creation, using the weak and impoverished as tools in theie endless battle to maintain control. They will keep at it until they are themselves eliminated.

Boochani’s is a story repeated ad infinitum, but one whose truth must be told lest we forget our own humanity. I toured southern Africa in 2003 in company with a young Kurdish student from London, who was studying law to become an advocate for his people rather than live a rich barrister’s life. His dedication to his people was a lesson I won’t forget.

The point for me, in the short term, is the challenge to endure a painful read, if only to honor the writer’s courage and persistence to remain human in the face of inhumanity. A reminder that we must be vigilant or else suffer the same fate.

Beautiful and important words, Elizabeth. I sit here and work on a novel and ask myself if anything I write has meaning when suddenly our world is in turmoil and you touch on issues we all want to ignore but cannot or should not. Our planet is struggling with global warming and the peoples of earth will be moving and moving some more to find places where they can SURVIVE, escape storms and droughts. More people asking for food and a place to sleep. We must read and praise those who inform us. And what power do we have each day as we sit and write? Empathy. Bring it onto the page so that it will flow out into the world.

Yes, this is an eloquent and profound essay, Elizabeth. It made me feel both sober and optimistic about writing and life in general. I see that, as of my reading, this post has been viewed 430 times. That in itself is a remarkable thing. Words like yours need to be heard far and wide (especially at this moment in history). A message in a bottle bobbing on the ocean.

It is difficult to go up against Solzhenitsyn and the classics – and narrative non-fiction in general – with fiction, but there are many areas of the world we share which have not yet been explored thoroughly with stories set in them because indie marketing is hard for literary and mainstream fiction, and traditional publishers only have so many slots in their catalogs.

Fiction has an important place: its additional distance from difficult subjects makes more readers willing to tackle a novel (such as Uncle Tom’s Cabin or Ordinary People) over a searing report of reality. You can’t develop empathy if you can’t get to a reader’s mind.

Reality must be explored, and the first-hand non-fiction reports of this nature are the beachhead. After and alongside that, fiction steps in.

Liz, I always enjoy your thoughtful introspective commentaries. As usual, I now have another author I will need to read. Thanks for the connection.

Thank you for sharing your astute reading of Boochani’s book. Your essay reminds us of the power of the pen and the shared responsibility we have in reading, listening to, and learning from stories such as Boochani’s.