Turning a Terrible Truth into Compelling Fiction

By David Corbett | September 13, 2019 |

This post is about series of vicious murders, a class I conducted on how to fictionalize such horrific events, and a student who taught me something important in the process.

This all took place late last month at the Book Passage Mystery Writers Conference in Corte Madera, California. For the past several years, I and fellow faculty member George Fong—former FBI Special Agent, now security head for ESPN and a novelist himself—have conducted a class where we take a criminal case, outline the facts, and then ask the participants how they would go about fictionalizing the material. The past two years, we’ve added Jim L’Etoile to the mix, a longtime veteran of the criminal justice system (he’s the son of prison warden)—and, you guessed it, he too is a novelist.

George, given his law enforcement background, has normally led the way by presenting the case; Jim and I have then led a group discussion on how to approach what George has presented as source material for fiction, asking such questions as: Who is the protagonist? Should there be a narrator? Who should have POV status? Where should the story begin? When should the identity of the criminal(s) be revealed? How will answers to these questions fundamentally change the tone, pacing, and dramatic tension of the narrative?

In the past, George has presented cases he has personally worked on, including the Yosemite murders and a Russian mafia kidnap-extortion case out of Los Angeles.

This year, however, he decided to look beyond his own experience and instead present a headline-grabber that many of the conference participants would surely know about: the Golden State Killer case.

George reached out to Steve Kramer, an attorney who previously worked in the FBI’s Los Angeles office, who, despite not being a field agent, turned out to be instrumental in identification and apprehension of the criminal in question, Joseph Deangelo. He simply took it on himself to solve the case which, at the time he got involved, had lain dormant for years. He specifically worked closely with Contra Costa Sheriff’s Detective Paul Holes, who had responsibility for several open cases believed to be linked to the suspect then already identified by the moniker the Golden State Killer.

[Note: Though Michelle McNamara’s incredible true crime book, I’ll Be Gone in the Dark: One Woman’s Obsessive Search for the Golden Gate Killer came out not long before law enforcement identified and arrested Deangelo, it did not, as some believed, point investigators to him as a suspect. Their work, which relied largely on DNA evidence, was independent of McNamara’s.]

During our workshop, George laid out the most salient facts of the case for the participants in a Power Point presentation:

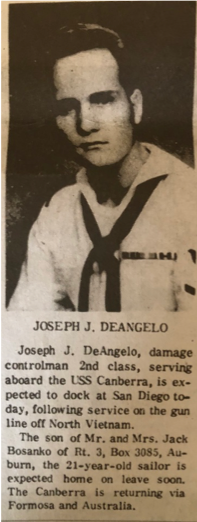

- Joe Deangelo was a Navy vet who routinely exaggerated his service experience, claiming to have been in combat when he was an on-board carpenter nowhere near a battleground.

- He became a police officer, working in Visalia, California, and was working in that capacity when he began his decades-long crime spree. He was ultimately fired for shoplifting—the items he stole, ironically, were to be used in his burglaries—but even after he was fired his training gave him unique insight into how to evade arrest.

- He stands accused of 60 home invasions, 50 rapes, and 13 murders. These crimes affected at least 106 independent victims. He locked children inside bathrooms while he raped and/or murdered their mothers, or tied up husbands and placed perfume bottles or other objects on them saying that if they struggled to get free, the object would fall to the ground and give them away, at which point he would kill everyone in the house.

- Deangelo began as a serial burglar near Visalia, California (north of Los Angeles), where his mother lived and where he first became a police officer in nearby Exeter. In just this one locale, he is believed to have been responsible for over 100 burglaries and one murder (the father of his first rape victim, a 16-year-old girl).

- Deangelo moved north to the Sacramento area after this initial killing and resumed his crime spree. It was here he was fired from his job as a police officer, and it was here he escalated from burglary to rape.

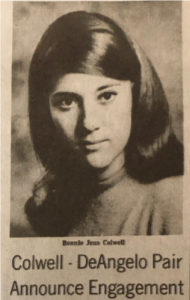

- At age 28 he became engaged to Bonnie Cowell, an 18-year-old lab assistant working at Sierra College where Deangelo was attending classes. The engagement didn’t last long—Bonnie, who was from a sheltered background, complained that Deangelo was insatiable sexually, hurt her physically during sex, and didn’t seem to care about the pain he was inflicting. She broke things off and moved away. (Important Note: During the rape of one of his victims, Deangelo blurted out, “I hate you, Bonnie!” Investigators didn’t know what to make of this at the time, as Deangelo’s identity, and thus Bonnie’s, was unknown.)

- Deangelo’s crime spree continued for nearly a decade. One of the things making it difficult to apprehend him was the fact he committed his crimes in numerous different locales from one end of California to the other, with investigators unaware they were chasing the same suspect.

- However, Sergeant Richard Shelby of the Rancho Cordova Police Department was the one law enforcement officer who worked longest on the case.

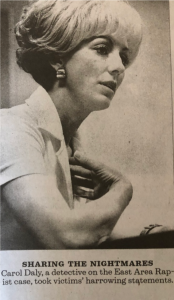

- Assisting Shelby was Detective Carol Daly, who interviewed each of the rape victims, took them to the hospital for treatment, and stayed connected with them as the investigation proceeded. Worn down emotionally and psychologically by the continuing onslaught of cases, she ultimately left the sex crimes unit, asking to be reassigned to homicide, so she could finally close a case.

- Deangelo’s crimes remained unsolved for over two decades. Ultimately he was identified through DNA. Once he was arrested, his former fiancée, Bonnie, was notified. She had no idea that he had committed his crimes, and felt overwhelming guilt that she had not been able to recognize his capacity for evil and do more to stop him from harming so many people.

- The survivors of Deangelo’s crime spree formed a support group, identifying themselves by the number given them regarding their place in the line of succession of his victims—e.g., “I’m Number 10.”

With those facts in hand, we now presented the matter to the participants and asked how they would go about fictionalizing this story.

The first consideration: Who should be the protagonist? Normally, Sergeant Shelby would be a prime candidate, but he retired without solving the case. Steve Kramer and or Det. Paul Holes might serve, but they came to the matter late and their work was largely restricted to analyzing evidence collected years before—i.e., there would be no chance to portray them scrutinizing crime scenes or interviewing victims or witnesses.

These shortcoming could be overcome, of course, but they had to be recognized for what they were. Neither Shelby nor Kramer could serve as a single voice of the entire investigation. That wouldn’t be fatal—since it’s fiction, you could simply create a single investigator who did follow the entire case from beginning to end. Or you could simply have Shelby begin the investigation, retire with a profound sense of incompletion, and then have Kramer pick the case up years later. This would pose the risk of breaking the dramatic thread and dissipating tension, but that could be overcome through any one of a variety of techniques—principally by keeping the focus on the unsolved killings. Otherwise you would likely need some sort of objective, all-knowing narrator, but that might undermine the intimacy of the narrative

This echoed another concern—a simple recitation of the facts seemed inadequate. It would make the narrative too similar to true crime, and if that’s the goal, why bother with fiction at all? The point of fictionalizing the story is to give voice to the characters who otherwise have only been seen from the outside.

Carol Daly possessed the same limitations as Shelby and Kramer, but her intimate involvement with the victims, not to mention the damage it did to her own psyche, made her a more interesting choice as a detective-narrator.

Bonnie Cowell could provide a fascinating perspective. Though she was unaware of the crimes as they were happening, she could recount them as part of her own attempt to comes to terms with her own sense of culpability for being too naïve to see Deangelo for who he was. This choice would introduce a new element—the “drama of the telling”—deepening the narrative by making the recitation of facts a dramatic act itself, with the narrator struggling to come to some understanding of what those facts mean in a distinctly personal way.

Once that element of “the drama of the telling” was introduced, we discussed considering the viewpoint of the surviving victims. The idea of introducing the story with, “I am Number Ten,” and having that individual tell at least part of the story as a form of coming to terms with what happened to her, soon began to seem to most of us as a particularly compelling way of telling this story with the poignancy, terror, and intense personal immediacy it deserved. This narrator–or several victim narrators–could stand in for the others, analyzing the other crimes as to how they conformed or differed to what happened to htem, and what that might mean.

I then wondered if a first person plural narrator, as in The Virgin Suicides, might not be a way of allowing all of the surviving victims to speak as one (without sacrificing their singularity should it be required—i.e., individual victims could come to the fore and then recede back into the group as needed for dramatic purposes).

Taking this further, I wondered if the “drama of the telling” might not be used the way it is in Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, where the narrator, Marlowe, struggles not only to understand what Kurtz meant by, “The horror,” but struggles with how to convey that to his listeners. Conrad’s purpose was to point toward a source of unnamable terror lying not just at the center of the imperialist project but in the very heart of man, something ineffable and paralyzing to behold, and yet inescapably true. Might not our group of victims be grappling with just such a source of nameless dread and horror in the person of Joseph Deangelo, like the embodiment of some preternatural human inclination toward predation, terrorization, and unspeakable cruelty, while at the same time puzzling over what it meant that he chose them as his victims.

This was when the teacher learned something from one of his students. Amanda Conran, an award-winning author of YA mysteries (The Lost Celt), called out from the back in her distinctive British accent that she believed referring to Deangelo in terms of some inexpressible horror gave him too much power. It elevated him to a station he did not deserve. Rather, the victims should be striving to understand him and what he did in the fundamentally depraved but all-too-human terms of his crimes, not some spooky abstraction. He was a perverse coward who hated women because of his own feelings of abject inadequacy, not some Conradian force of evil.

Now, there is such a thing as “psychopathic inflation,” a term coined by Jung, by which a criminal, often a sexual predator, believes he becomes a godlike being in the course of committing his crimes. This is the premise of Thomas Harris’s depiction of Francis Dolarhyde in Red Dragon. Francis is obsessed with William Blake’s painting The Great Red Dragon and the Woman Clothed with the Sun. This vision informs how Francis views not just himself but his sadistic longings and murders. He is not the mere product of his painful, humiliating past. He is a monster in the truest, greatest, most transcendent meaning of the word. He creates a pathological identification so extreme that he doesn’t merely see the Red Dragon as an analogy—he becomes the Red Dragon as he terrorizes and kills his victims.

Nothing of the sort applies to Deangelo, not that we know of. So Amanda’s criticism seems well founded, and it in no way undermines the power of using the victims’ combined or individual perspective(s) for the narrative point of view, allowing them to process their recovery and come to terms with what happened as they recount the story of what took place.

We left the discussion there, but I wonder if we might not pick it up again here. How would you tell this story: Whose perspective would you use to frame the narrative? How many POV characters would you use? Which ones? Would you include Deangelo as a POV character? Why or why not? Would you create a composite detective as your main character or even narrator? Would you prefer Carol Daly or Bonnie or one or more victims as your narrator–if so, would you employ a “drama of the telling” strategy for the narrative?

Please Note: Once again (I know, I know…), I’m a moving target on a post day. Today I’m heading off to attend the wedding of—I’m not making this up—the daughter of my pedagogical sidekick mentioned above, George Fong. I will try to get to your comments at some point during the day. Meanwhile, hammer this out among yourselves.

When you mentioned his girlfriend Bonnie, I immediately thought of the Netflix movie – Extremely Wicked, Shockingly Evil and Vile – which tells the story of Ted Bundy through the eyes of a girlfriend who could not believe him capable of his deeds. It was a compelling way to tell the story opening with their romance, then following Bundy through his murderous rampage, and the slow dawning on the girlfriend of the terrible truth about someone to whom she’d been engaged.

Given the Bundy movie, though, using Bonnie as the protagonist might be viewed as unoriginal for the telling of this tale. I’d start with the FBI Agent who solved the case and work backward. (But then, I used to work at the FBI.)

Congrats, Mary. You are the first to bring up the Bundy predecessor despite a roomful of mystery writers and aspiring mystery writers. I agree that without some unique innovation this would make using Bonnie’s POV seem derivative. Thanks for chiming in.

Mary, I watched that movie with my grown kids a few months ago and it was very interesting to see how the girlfriend had something that pricked her, yet she kept on seeing Bundy. Kind of scary to see his hold over women.

I know, Vijaya, and part of it was that he was an affable, good-looking guy! So sad that he was so evil.

I will avoid commenting on the curious subtext of “villains should be ugly” and the Prince Charming alternative implications.

Oops. Too late.

:-)

Ha ha!

Interesting post, David! I like telling the story through the victims’ eyes, but I think I might add one more POV, that of Deangelo. It is fiction, after all, and adding brief views into his internal thoughts as he plans and/or commits his crimes would ratchet the tension even higher. It might be informative to watch him devolve into the evil creature he became. The reader would observe him as he selects his as yet unnamed next victim, etc. By juxtaposing the victims’ and Deangelo’s POV’s, one can paint a more complete picture, in my opinion.

This approach, while compelling, will require a skilled hand. Only a few writers, in my humble opinion — Patricia Highsmith, Thomas Harris, John Fowles, Jim Thompson — have develed into the mind of someone like Deangelo and crafted something credible, compelling, and sufficiently terrifying.

You are a brave man, David, and others too, who are willing to read understand the psychology of horrific murders and write about them. Although I have read a few gruesome books in my life, even before I pick them up (morbid curiosity?) I try to keep an emotional distance. It’s hard. I could never write this story. But I am interested in seeing how a person goes to the dark side and would want to know how he got there. So my interest is more in his development, his childhood, and whether there were any clues. Ex. Something About Kevin. I thought it a brilliant book.

I’m not sure we’re all that brave. Can;r mind our own business, perhaps. Something About Kevin is an inspired comparison. Thanks for mentioning it.

Thanks for this case study, David. It raises more questions than can be taken up here, but three things stand out for me.

1. I like your idea of sequential narrators handing over the investigation to the next detective until the case is broken. That would be a greater challenge for the writer, but it would place the emphasis on the investigators, rather than on the criminal and the crimes themselves. Unless the project is tabloid-oriented, I would think the investigation is the focal point.

2. Your student Amanda Conran hits the mark: I understand her to say that treating the criminal as a monster, a thing out of nature (The horror! The horror!) not only informs his character with more power than he deserves, but it distorts the truth. He was a serial rapist and murderer, and he slipped away for many years. Why that happened is a story in itself. That means the story needs to give readers some appreciation for how the criminal evaded discovery for so long. I certainly would want to know this. To say his crimes were committed all over the state isn’t sufficient. Surely, he left signatures, indicators, elements that would have created a trail of some kind. If that’s not the case, then the theme is very dark indeed. How many of the thousands of unsolved murders can be accounted for in the same way? But maybe that should be the point.

3. Your post relies on and makes good use of graphics, in the form of photos. This leads me to wonder whether the choice of medium for telling this story should be the screenplay or teleplay, not the novel. It just feels better suited to film. For me, print’s strengths are voice and style. The facts you give us seem better suited to the unique tool kit that film has to work with.

Thanks for a fine insider’s post.

Thanks, Barry. I belive the McNamara book is being made into a film. And there is certainly a lot of room for that. But I also think there’s a lot of room for interiority in this story, especially from the victims’ or even Denagelo’s POV. But even the POV of Richard Shelby, who tried for years but failed to catch the killer, could be fascinating. My personal favoriate, though, remains Carol Daly. Imagine being so burned out by listening to the horrific accounts of the first rape victims and being so torn up by being unable to solve those cases that you’d rather work on murders. (In a brief amount of time, this same suspect woudl give her that opportunity, though she didn’t know that — but you could create a fictionalized version of her that did, and I think that voice could be compelling.)

David, this is fascinating on so many levels. Rather new to California, I followed all the articles in the LA Times and also read about Michelle MacNamara’s book, how the case seemed to possess her and that she died before Deangelo was found and arrested. I was similarly overcome by a kidnapping and murder that happened in Chicago in the 80s and all of it became something I could not let go of. It fueled the novel I still hope to publish.

Your analysis of how to tell this decades long painful story, the pros and cons of the various POV, stimulates a writer’s thinking. It also supports that evil in the world is often at the forefront of stories that writers of great merit and fame have written about forever. But there are no satisfying endings to this story. Only pain and loss. Maybe I began my novel in the hopes that I could wash away the terror I felt from the real event. Some sort of catharsis. Thanks again.

Well, Denagelo was ultimately caught due to an FBI lawyer who decided somebody had to try to solve this thing. So the ending isn’t toally bleak. But it’s hardly a Hallmark movie of the week, either, that’s for sure.

I don’t think ANY crime where there is rape and murder is a Hallmark movie. Catharsis doesn’t have to be saccharine, it can attempt to find truth. With the Deangelo murders–the truth is that he is evil, deserved to be caught and the FBI lawyer is one of our modern heroes.

Turning the Deangelo case into fiction poses hard-to-choose-between-them trade offs.

The natural choice to tell the story as crime fiction is undercut by the lack of single protagonist. The understandable choice to tell the story of multiple victims, or of the guilt-ridden fiancé, leads to an aftermath story which will struggle for dramatic action. The killer himself, as Conran rightly asserted, does not deserve a voice.

The difficulty may lie in feeling that the whole Deangelo story is *the* story, that somehow it must all be encompassed and its full horror processed. Actually, the best novel about Deangelo may not revolve around Deangelo at all. I think of novels like Emma Cline’s “The Girls”, inspired not by Charles Manson but the young women who became his “family.”

Cline’s novel, in fact, is not a fictionalized Manson Family tale but one transposed into fictional characters and events. In other words, to address your topic, getting away from Deangelo altogether may be the best way to go.

Edgar Allan Poe’s Murders in the Rue Morgue, for example, was also fiction inspired by a true case but only loosely. (See Daniel Stashower’s excellent account of the original case and Poe’s involvement with it, “The Beautiful Cigar Girl”.)

My two cents.

Apologies, the Poe tale inspired by the true case of “the beautiful cigar girl” was “The Mystery of Marie Roget”, not “Rue Morgue”, as I said above.

My head is quietly exploding over the fascinating prospect of not making the story about Deangelo at all. This brings us back to the survivors — “I am Number Ten” — and focusing on them dealing with some unnamed trauma, only gradually revealing what it is. Powerful. Make it about the women, not him.

I realize I’m coming in late, but this topic really engaged me.

I think a story this time-spanning would need to have one voice to make it cohesive. A survivor or relative of a victim from early on that is working with the police to solve this. A citizen detective or a child that grew up to become a cop. Someone that would give voice to the victims and the range of destroyed lives left behind.

And by no means would I give voice to the perp. He deserves no sympathy.

I would want the DeAngelo character’s POV to be used occasionally to show him rationalizing his deeds to himself, thereby making them entirely acceptable–even good–in his own eyes. If that is done in such a way as to enlist the reader’s sympathies, so much the better in heightening the tension.

My gut reaction is to go with Kramer – the one who actually solved the case. Sounds like he obsessed over it, so it shouldn’t be hard to have him reaching out to connect with previous investigators, victims and/or the people who knew them – after all, this is fiction, so you can create some connections that might not have really occurred. In doing so, those people could flash us back into the past, without necessarily changing the protagonist. Or are there some unwritten-but-understood rules about how true to the fact you’re supposed to remain?

In addition to thinking about the people involved, I think this particular crime also offers a lot of interesting fodder in HOW it was solved: uploading DNA samples into a common online product – NOT a police tool – that regular people use for tracing their genealogy; the forensic genetics and serious data-crunching that were involved; and of course the dogged obsession of the guy who finally cracked this.

Fascinating stuff. I could get into a whole ‘nother tangent about the personal impact and moral implications of fictionalizing the lives of real people who live (or lived) in our own era, all in the name of creating a piece of entertainment (Tarantino’s new flick comes to mind), but I suspect that could take up an entire separate post.

The use of the word “entertainment” can be problematic, because it suggests a somewhat lower purpose than, say, “art.” I don;t know who said it first, but I believe strongly in the credo: “There’s nothing wrong with entertainment. Just entertainment that insults your intelligence.” I think what we’re trying to do here is make sure we don’t insult anyone’s intelligence — or prey on someone’s misfortne for a story. Rather, we’re trying to see in real events a larger, more universal account. But I agree this point could take up another entire post. Thanks, Keith.

David:’

As useful, you’ve given us a lot to think about, not only on literary technique, but on our role as writers in society. Thank you!

The fact that Deangelo’s crime spree stretched over several decades adds another element to the question of choosing a narrator: how did changing attitudes and crime-solving tools (such as the shame of rape, the use of psychological profiling, and advances in DNA identification) affect the investigation? “Handing off” the narrative to a series of POV characters could pose questions about society that readers might find as compelling as the story itself.

Fascinating—if grisly—stuff, David. I did some research on a murder that happened in Santa Cruz in the 80s that had lots of dramatic (fame, drugs, sex) elements, and the murderer got away with it. I did consider writing a nonfiction account, but the main suspect is still alive, well-off and litigious, so…

My first thought on fictionalizing it was to have the murder victim be a first-person voice, ala The Lovely Bones, but thought that might be cheesy, or that I couldn’t pull it off with anywhere near the grace and skill of Alice Sebold.

Anyway, thanks for another provocative post.

So fun seeing Amanda Conran mentioned, as she is my critique partner. :) But I have a few questions. I am also a 2x published YA author, so writing in this genre is newish to me. My question is, to what degree can you fictionalize a true event? Can you make up characters and change basic facts, and claim to “base your story on a real story,” or are you much better off doing as much research as you can, sticking to the true story, and only fictionalizing the POVs of characters and only making up facts when they are simply not known? If the first choice, would you recommend changing to all new names to protect the author? And finally, can you get sued for fictionalizing characters where the relatives involved are still living? Appreciate it! Sorry for all the questions. I am definitely going to that conference next time.

Hi, LB:

Those are somewhat technical legal issues that I suggest you research independently. I’d begin by Googling: ficionalizing real events and people. There are a number of valuable sites that come up immediately. Good luck!